The Sift: Election aftermath | Ballot misinfo | “Latino vote”

|

|

Teach news literacy this week |

|

Election aftermath Misinformation and conspiracy theories thrive when curiosity and controversy are widespread and conclusive information is scarce or unavailable. The deeply polarized 2020 presidential election not only produced these conditions, it sustained them as ballots in a number of swing states with narrow vote margins were adjudicated and carefully counted.

|

|

|

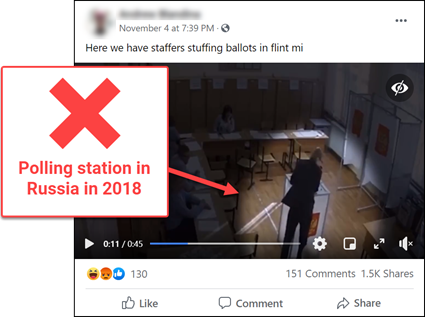

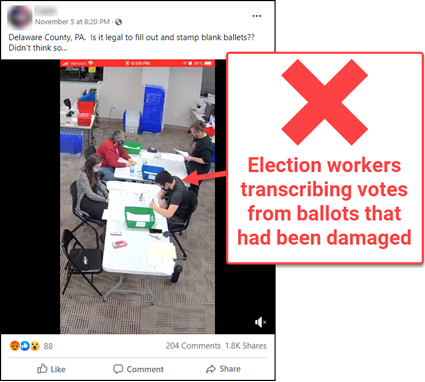

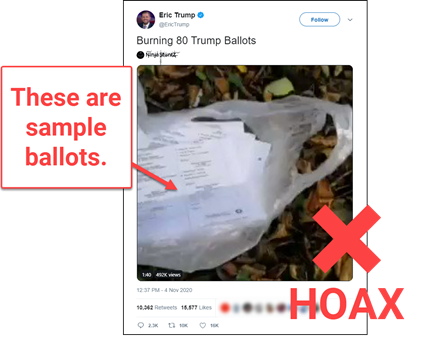

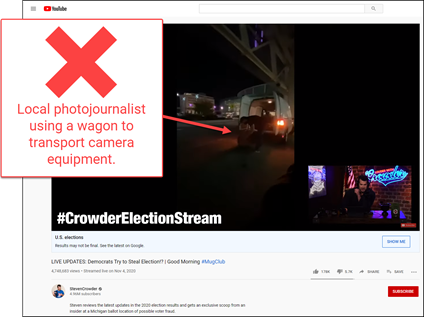

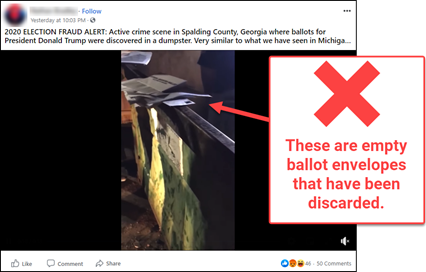

Viral rumor rundown  NO: The video in this viral Facebook post does not show election workers stuffing ballots in Flint, Michigan. YES: It is a video showing alleged ballot stuffing in Russia in 2018.  NO: The video in this Facebook post does not show election workers in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, illegally filling out blank ballots. YES: It shows them transcribing votes on ballots that were damaged by an extractor so they could be scanned. YES: This is a normal process. NO: This was not the only clip of Delaware County election workers transcribing ballots to go viral as false evidence of fraud last week.  NO: The video in this tweet does not show 80 Virginia ballots for President Donald Trump being burned. YES: It shows a bag of sample ballots from the city of Virginia Beach being burned. YES: Unlike the sample ballots in the video, authentic Virginia ballots have bar code markings, according to Virginia Beach officials.  Images released by the city of Virginia Beach demonstrate distinct differences between legitimate ballots (right) and the sample ballots that appear in the false viral video (left).  NO: This video does not show a person delivering or moving ballots outside of a ballot counting location at the TCF Center in Detroit. YES: It shows a photographer for WXYZ-TV, the ABC affiliate in Detroit, using a wagon to transport his equipment outside the convention center. YES: This rumor appeared on the Texas Scorecard, a partisan blog, before it was amplified by conservative YouTube show host Steven Crowder during his Nov. 4 livestream.  NO: Ballots for the 2020 election were not found in a dumpster in Spalding County, Georgia, as this Facebook post claims. YES: There were empty envelopes from mail-in ballots in a dumpster outside the elections office in Spalding County. |

President Donald Trump spoke during the early morning hours of Nov. 4 following Election Day, alleging fraud and claiming victory even as results in several states were still uncertain. News organizations that sent mobile news alerts about Trump’s remarks varied in how they handled the claims. Let’s take a closer look at word choice and framing as we consider how these factors shaped some news organizations’ approach to reporting on the president’s remarks in their efforts to be fair, accurate and fast. Grab your news goggles, and let’s go!

Discuss: What thoughts do you have about how these five news organizations worded their alerts? Which alerts did you think were the best? Why? Which, if any, were problematic? Why? Did any of the word choices show potential bias? If so, how could those alerts have been more accurate? |

|

★ Sift Picks Featured “Election results - PBS NewsHour special coverage” (Yamiche Alcindor, PBS NewsHour). Quick Picks “With many children still learning from home, kid-focused news products aim to fill some gaps” (Rachel del Valle, Nieman Lab).

“Joe Scarborough cheers sleepless Steve Kornacki after MSNBC calls it for Biden: 'Big pay raise, baby!'” (Sara M. Moniuszko and Kelly Lawler, USA Today).

“Opinion: Why can’t a generation that grew up online spot the misinformation in front of them?” (Sam Wineburg and Nadav Ziv, Los Angeles Times).

|

|

|

What else did we find this week? Here's our list. |

|

Thanks for reading! Your weekly issue of The Sift is created by Peter Adams (@PeterD_Adams), Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington (@HannahCov) of the News Literacy Project. It is edited by NLP’s Mary Kane (@marykkane). |

|