Without context and consideration, numbers can mislead

There’s a common phrase that “numbers don’t lie.” This refers to the idea that statistics and data that are used to back up arguments are faultless. But even when numbers and data are correct, people and organizations with their own agendas can use them to mislead because they don’t tell the whole story on their own.

That’s why quality news organizations and researchers do more than just present data. They put it in context and explain how they collected it, analyzed it, built their database and made it verifiable. The Global Investigative Journalism Network provides some excellent examples of such work.

SAS, a pioneer in the data management and analytics field, helped us explain how we can transform data into intelligence and why numbers can sometimes mislead.

When we use numbers to represent the world around us, those numbers are almost always an estimate. We don’t know the exact number of people in the world at any given time, or the exact amount of carbon emissions, or how much money is being spent. Though it is theoretically possible to get exactly accurate values for these, the practicalities of our world mean we must rely on estimates instead.

And some issues can’t be quantified. For example, people’s preferences, health or behaviors are hard to boil down to a single number or value. How much do you like dogs? Do you eat healthfully? Is there a single value that can accurately capture the wide range of people’s answers to these questions? No.

That is why it is always important to understand the context in which data is collected and presented. What do the values you see truly represent? What do they tell you and what don’t they tell you? What is the person using the data trying to convey? Does the data support their argument?

Engaging in critical thinking around these questions will help you to be a better consumer of data. All kinds of information — including statistics, charts and graphs — can be presented in ways that mislead. That’s why you must evaluate them critically.

Data and numbers are powerful tools for building arguments. They add credibility and can help prove a particular point. They can provide insights into the world around us and help us better understand an issue. But the idea that numbers don’t lie is false.

So remember to evaluate data critically and pose questions of the information that could help you better understand what is presented, and lead you to wonder about the questions the data doesn’t answer.

Think hard before becoming a co-conspirator

To be human is to see patterns in the world around us. And although making sense of them is how we have thrived and evolved, sometimes we contort facts into patterns that don’t really exist. Such mangled thinking can turn a set of discrete facts into a conspiracy theory.

Conspiracy theories are tough to untangle, both because of the cognitive reasoning that leads people there and because of the very nature of such theories.

Why our brains fall for conspiracy theories is complex. But in general, it’s based on confirmation bias — the practice of focusing on facts that support our existing ideas and overlooking or ignoring facts that contradict those ideas.

Also playing a role is “proportionality bias” — the belief that a huge event (such as the assassination of John F. Kennedy or the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks) was caused by something equally huge.

As for the nature of conspiracy theories, here’s one expert’s view: “The genius of conspiracy theories is that you can’t prove them wrong,” says Peter Ellerton, founder of the Critical Thinking Project at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia.

Conspiracy theories, he says, are based on fear and on people’s personal values, not facts. For example, that means that when someone is convinced that vaccinations cause autism, any specifics used in a counterargument can equally be used — erroneously, of course — to strengthen the conspiracy theory.

Like it or not, it seems that everyone is prone to falling for a conspiracy theory: We all see patterns. We all have cognitive biases. And sometimes it’s even true that twisted, unfair actions are behind certain events.

How not to fall into the abyss of non-sense?

Being aware that we might fall into the trap can help. And a 2017 study links news literacy practices with the steady thinking that keeps people from believing conspiracy theories.

In other words: To step away from the darkest, weirdest ideas, apply critical-thinking skills and research credible sources. And don’t believe a wild idea just because it seemingly cannot be disproved. That could be your cognitive biases blinding you to the facts.

Public service, not ad dollars, are at the heart of good journalism

Good ethics make for good journalism.

The Society of Professional Journalists publishes ethics codes from news outlets and journalism organizations around the world — and it has its own, too. These are principles meant to guide journalists as they report on events in the public interest. Running like a thread through all the entries is the idea that good journalists are loyal first and foremost to the public — and therefore to the truth.

Such loyalty requires, above all, an independence from influence and pressures that might shade how a journalist sees or reports the facts.

For example, if readers thought that a reporter was doing a favor for an advertiser by highlighting positive aspects of a service or product, or they suspected that a reporter was trying to support the editorial board’s stance on a contentious issue, such doubts would damage the credibility of both the reporter and the institution.

That’s why, at news outlets that adhere to the highest standards of journalism, reporters and editors do not work directly with the advertising staff and are completely separate from the opinion section (which typically includes the editorial board). Indeed, these outlets protect the independence of their reporters with policies that insulate newsrooms from the influence of advertisers, the editorial board and other opinion writers.

As anyone paying attention to news knows, news organizations are facing financial pressures as never before. That has, in recent years, led some journalists to urge other reporters to at least be more familiar with practices on the business side that keep the newsroom afloat.

In its 2014 innovation report (PDF), an internal committee at The New York Times wrote: “The wall dividing the newsroom and business side has served The Times well for decades, allowing one side to focus on readers and the other to focus on advertisers. But the growth in our subscription revenue and the steady decline in advertising — as well as the changing nature of our digital operation — now require us to work together.” Emphasizing different parts of the “business side,” the report goes on: “We still have a large and vital advertising arm that should remain walled off.” But there is now room at the Times — and elsewhere — to determine whether marketing efforts can build from reporting in ways not previously considered.

And while some lines are gray, the bright line of independence of reporters doing their jobs stays true, enshrined in ethics guidelines that remind readers and reporters alike that journalism’s first obligation is to the truth, and its first loyalty is to citizens.

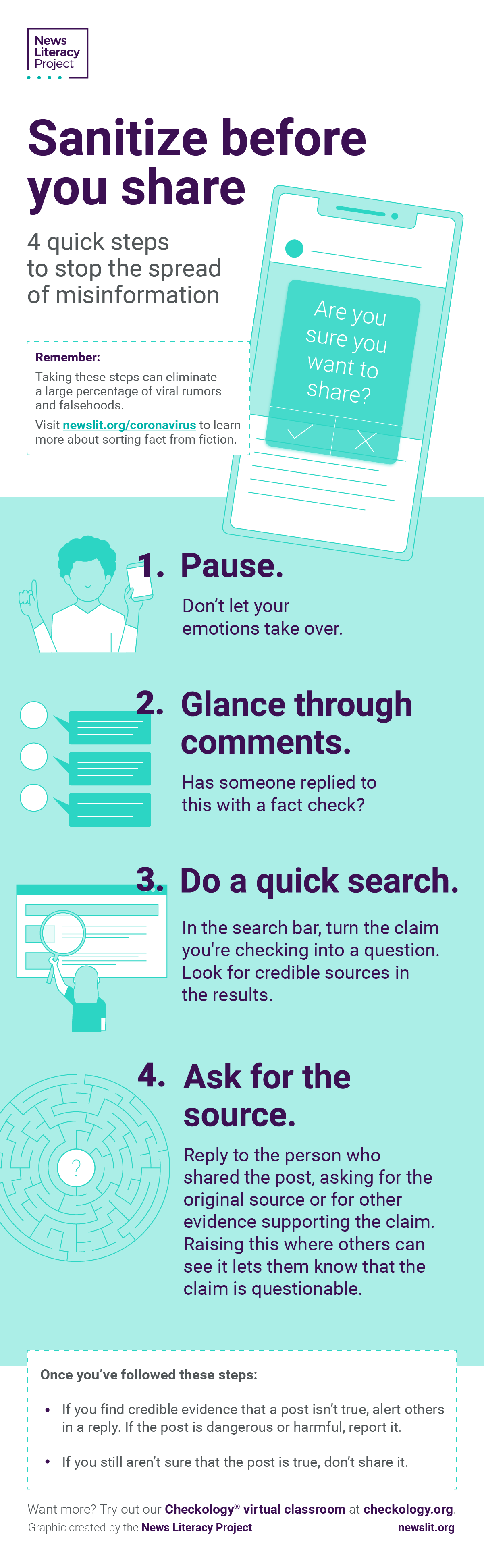

Practice good information hygiene: Sanitize before you share

Misinformation swirling around the COVID-19 outbreak underscores the importance of consuming and sharing online content with care.

Public health officials are urging us to practice good hygiene to help stop the spread of this virus — by washing our hands thoroughly and frequently, staying home as much as possible, and keeping a safe distance from others when we do go out.

We can also practice good information hygiene. Just adopt the four quick and easy steps below to help stop the spread of COVID-19 misinformation. If we sanitize the process around our information habits, we can prevent misleading and false content — some of which is hazardous to our health — from being widely shared and potentially doing harm.

Take 20 seconds for good information hygiene

It took the COVID-19 pandemic to get most people to adopt the hand-washing guidelines that health experts — like those at the World Health Organization — have recommended for years. (Studies from the mid-19th century showed that good hand washing could help stop the spread of disease.)

To kill germs, like the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, experts advise that you wash your hands for 20 seconds. That doesn’t mean limply running them under the faucet. You must use soap and water, scrub under your nails, between your fingers and on the backs of your hands. To be sure that you do this for 20 seconds, sing “Happy Birthday” twice.

This public health message has been repeated countless times during the COVID-19 crisis, including in videos showing various celebrities washing up.

Advice for good information hygiene

This guidance serves as an apt metaphor for practicing good information hygiene. Peter Adams, the News Literacy Project’s senior vice president of education, made the connection during a March 14 segment of NPR’s All Things Considered. Here is how Peter described it: “The equivalent of taking 20 seconds and washing your hands is very much the same in the information space. If everyone can take 20 seconds, investigate the source, do a quick Google search, stay skeptical, we can eliminate a great deal of the confusion and misinformation out there.”

Doing so is an important step in practicing good information hygiene and helping to stop misinformation’s viral spread. This is critically important during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a public health crisis, consuming and sharing false or misleading information can be a matter of life and death. And to help stop the spread of misinformation, pausing before you share content online is always important.

Learn more

For additional guidance on good information hygiene, check out NLP’s infographic Sanitize before you share

Look: The steps of sleuthing for accuracy

How do you know that the image you’re seeing online is truly what someone says it is? There are ways to suss out the facts.

- Look.

- Look again, more closely.

- Look at its origins.

- Look at it from a big-picture perspective.

Taking those four steps can help you discover whether an image is what someone says it is — so you’re not fooled into believing or sharing misinformation.

- Look. Observe the details. If the caption says that the event depicted is happening in Miami, you shouldn’t see heavy winter coats. If you’re told that the building you’re seeing is in London, there shouldn’t be cars with license plates from U.S. states.

- Look again. Take one of those details you’ve spied — a store name or a street sign — and search online to confirm its location. There may even be elements in the image — for example, a state flag in the distance — that you can zoom in on to nail down the location.

- Think backward. Conduct a reverse search. It’s particularly easy if you’re using the Chrome browser: Simply right-click on the image and choose “Search Google for Image.” If you’re using another browser, you can upload the image (or copy its URL) into TinEye. You might find dozens of webpages that include the image and confirm its origin (for example, a news service photo published by credible news outlets).

- Geolocate! You can also use Google Street View, a photographic feature that lets you virtually stroll much of the world. To learn more about this, use First Draft’s resource on geolocation, for that is what you’re doing: figuring out, or verifying, where on Earth the image you see posted online was taken.

First Draft, an international nonprofit addressing issues of truth and trust in the digital age, also has an overall primer that lets you hone your powers of observation by giving you the opportunity to practice your online sleuthing skills.

The most important step to take to know what’s real, of course, is the one that leads you to these investigative tools to start with. It’s taking the time to ask: Is that for real?

When correcting the record, make a ‘truth sandwich’

To err is human, to correct is divinely human. But in correcting the record, some ways are more divine than others.

Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society lays out the basics of how to correct the record, whether you’re an individual or a news outlet: Begin and conclude with the correct information, sandwiching the wrong information between. As Berkman puts it, “Make the truth, not the falsehood, the most vivid take-away.”

That’s because repeated information sticks with us, whether the information is accurate or not. We rely on repetition. The more something is heard, the more it’s believed.

Sandwiching errors also is a good approach because of how we respond to information. As Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert contends, when something is said, people comprehend in two steps. First, we hold the idea in our mind. Then, we decide whether it’s factual. That means when we hear or read something new, we consider the morsel of information, using it as the frame of reference for what comes next. By accepting it, even momentarily, we’ve started to digest it. Gilbert hypothesizes that the second step — of considering whether something is to be believed — is harder to do. Often, we simply skip this step unconsciously.

So what may sound like an interesting bit of trivia is important when it comes to crafting a correction.

Some researchers also urge those who write corrections to focus on simple, accurate statements (the correct information first), to clear up the misinformation.

And yes, corrections matter. A 2016 study suggests that even people with strongly held beliefs will change their minds when presented with facts that contradict those beliefs.

To repeat (because repetition is effective): Get your facts straight! When correcting a falsehood, state the fact first and last.

Citizens, like reporters, can be watchdogs guarding integrity and truth

One of the most significant, and most tragic, examples of a citizen acting as a watchdog of those in power occurred on July 6, 2016, when Philando Castile was fatally shot by a police officer in Falcon Heights, Minnesota. Castile’s girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, and her daughter were in the car as Castile, who was driving, was pulled over.

After a brief conversation with Castile, the officer shot him seven times — and within seconds of the final shot, Reynolds began recording and livestreaming the events on Facebook. “In doing so,” reporter Julie Bosman wrote in The New York Times, “she became not only a poised and influential witness, but a teller in real time of her own treatment by the police.” She also became part of a national effort to document police officers’ treatment of ordinary people, especially Black Americans.

Watchdog reporting is its own category of journalism, referring to scrutiny given to the actions of those who hold power and influence. These efforts to hold such forces accountable, when carried out by news outlets, include follow-up research and verification of facts to build a comprehensive report.

But ordinary people can witness and record incidents, too, and the point is the same: to bring troubling incidents to light by providing evidence, be it a photograph, a video or notes of a transaction or encounter that someone meant to keep secret.

When local newspapers close, journalistic oversight decreases, so the need grows even greater for coverage of parts of the community that might operate under the radar — for example, operations of businesses or activities of elected officials or others in positions of authority. For instance, area residents taking notes and asking questions at town meetings can help, as a columnist wrote in 2018 in the politics news outlet NJInsider: “My hunch long has been that local town and school board officials love opening a meeting and seeing no reporters or citizen watchdogs in the audience.”

Expand your view with lateral reading

What do you do when you encounter information that leaves you scratching your head — wondering whether it’s a credible news report, a subtly disguised advertisement or a provocative piece of propaganda?

If you simply go down the rabbit hole of the site that posted or created it, you likely won’t get the clarity or context you need to make an informed decision.

So instead of going deep, go wide: Employ lateral reading.

“In brief, lateral reading (as opposed to vertical reading) is the act of verifying what you’re reading as you’re reading it,” writes Terry Heick in “This Is The Future And Reading Is Different Than You Remember” on TeachThought.com, a website featuring innovations in education. The lateral reading concept and the term itself developed from research conducted by the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG), led by Sam Wineburg, founder and executive director of SHEG.

Lateral reading helps you determine an author’s credibility, intent and biases by searching for articles on the same topic by other writers (to see how they are covering it) and for other articles by the author you’re checking on. That’s what professional fact-checkers do.

Questions you’ll want to ask include these:

- Who funds or sponsors the site where the original piece was published? What do other authoritative sources have to say about that site?

- When you do a search on the topic of the original piece, are the initial results from fact-checking organizations?

- Have questions been raised about other articles the author has written?

- Does what you’re finding elsewhere contradict the original piece?

- Are credible news outlets reporting on (or perhaps more important, not reporting on) what you’re reading?

The book Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers sums it up this way in the chapter “What ‘Reading Laterally’ Means”: “Lateral reading helps the reader understand both the perspective from which the site’s analyses come and if the site has an editorial process or expert reputation that would allow one to accept the truth of a site’s facts.”

If other reliable sources confirm what you’re reading, you can feel confident about its credibility.

Breaking news reports can be hit or miss, because accuracy takes time

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated many areas along the southern coast of the United States. The storm also served as a case study of the best and worst in reporting: The worst was reflected in early reporting of rumors published without verification; the best showed in some thorough follow-up coverage.

It’s not known how many people died as a result of Katrina; estimates have ranged from fewer than 1,000 to more than 1,800. The Category 5 storm slammed into the Gulf Coast and, most notoriously, New Orleans — “notoriously,” for it was that city that bore the brunt of the high winds and hard rains and that showed up most often in media reports across the country and world.

As the levees crumbled and much of the city flooded, early news reports led to what Los Angeles Times reporters described a month later as “a 24-hour rumor mill at New Orleans’ main evacuation shelter.” “Katrina Takes a Toll on Truth, News Accuracy” recounted tales published during the storm that were exaggerated or just plain wrong. Some news outlets published information about rapes, robberies and drownings that later proved groundless. Even the city’s mayor and police chief were behind some of the bogus information.

The lesson here: Producing a credible report as big events unfold takes time, because verifying facts and quotations takes time.

However, given that time, news outlets can shine as they track down and report credible information that is not always available in the chaos of breaking news. One year later, in 2006, two outlets in the eye of the storm — The Times-Picayune in New Orleans and the Sun Herald in Biloxi-Gulfport, Mississippi — were honored with the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for their reports on Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath, including articles that examined the failures at local, regional and national levels that contributed to the devastation.

Readers, viewers and listeners craving information as major events unfold should beware: Verification takes time. Even in the rush of breaking news, look to see if an outlet has noted its efforts to verify information. Only time can tell what is true — time, and good reporters.

A healthy reaction to information is to ask ‘What’s the point of this?’

We’re all moving targets when it comes to information aimed straight at us, whether the darts headed our way are text messages, social media posts, photos, emails, longer written pieces, games, GIFs or videos. Savvy citizens of the internet know to start with one question when something whose creator they don’t know hits their screen: What is the main purpose of this information?

Especially if you first think is that what you’re seeing is news, think harder: Is it intended mainly to entertain you? Sell you something? Persuade you of something? Provoke you? Or is it information presented to document or inform? As the “InfoZones” lesson in our Checkology® virtual classroom explains, understanding the following categories of information helps you know how to process what’s coming at you:

- News: Informs you, through objective reporting, about local, national and international events, issues and people of significance or of interest.

- Opinion: Persuades you, ideally through the use of fact-based evidence, to adopt a specific point of view about an issue or event.

- Advertising: Sells you a product or service.

- Entertainment: Amuses, pleases, relaxes or distracts you.

- Propaganda: Provokes you — often by using false or distorted information to manipulate your emotions.

- Raw information: Documents an event or trend. It has not been analyzed, checked, edited, explained or placed in any context.

There’s nothing wrong with going online to be entertained or amazed. But to avoid being unwittingly zinged by something that you assume is verified news but is, rather, an ad or unedited video, start with this healthy question: “What is the primary objective or purpose of this piece of information?”

Once you’ve answered that, you’re prepared for what comes your way. Whether you laugh, shout, buy or cry, you’ll be in charge of your reaction — and you won’t end up spreading what you thought was truth but instead was something taken out of context or designed to manipulate.

Is that the whole truth?

Even when a piece is clearly marked “opinion” and offers facts that you know are accurate, what you’re reading or seeing might not be the whole truth. That’s because opinion writers and TV commentators are in the business of trying to change people’s minds. That means they might include only the facts that support their viewpoint — and ignore others — when making their case.

That’s not to say opinion pieces are bad. Well-crafted opinion pieces, be they editorials, editorial cartoons, videos, or written or spoken essays, can be inspiring and motivating — especially when viewers understand that what they are seeing reflects a particular perspective.

How do you know when there’s a slant? Careful viewers check their gut, and their facts. They consider several factors that can make opinion pieces so powerful and, sometimes, misleading.

What’s missing? Facts and statistics can be accurate but still present only part of the picture — the part that favors a single point of view. And beyond the quantitative aspects are the qualitative ones. Are valid perspectives left out? Only through research can someone know if a piece presents the full context.

Sources cited: Do the outlets or research firms cited have an explicit bias? Again, researching the backgrounds of experts and companies cited can reveal if they are credible.

Language: Are the authors using words and phrases like “terrorist,” “vigilante,” “bureaucrat” or “freedom fighter”? Loaded language can play a role in shaping an opinion without your even realizing it.

Of course, there is always the danger that the author is using information that is just plain wrong. When flat-out lies are used, opinion pieces become something else: propaganda. But commentary has a long and proud history in America. Society is best served when those who would change others’ minds communicate their aims clearly. Most importantly, news consumers must apply critical-thinking skills to all they read and see and decide for themselves whether the arguments are well-made and fair.

Honest praise or an ad? Influencers blur the line

There’s big money to be made in the world of social media influencers, but at whose expense? If you’re unaware that someone you follow online is being paid to make certain products sound great, you could be the one paying the price.

The concept isn’t new — who hasn’t tried a new restaurant, clothing brand or service because a trusted friend likes or suggests it? — but “influencer” as a marketing term has evolved as companies no longer can rely on traditional sales tactics to stand out. Today, marketers promote their goods by turning to people with large online followings — not just A-list celebrities, but Instagrammers and YouTube stars as well.

And as businesses give more ad dollars to social media influencers, the guidelines to help consumers aren’t keeping up. As a November 2018 article in Wired said, “Many users don’t view influencers as paid endorsers or salespeople — even though a significant percentage are — but as trusted experts, friends, and ‘real’ people.”

That’s one reason the Federal Trade Commission expanded its rules designed to enforce the credo that credible news organizations have long lived by: Don’t deceive the audience.

According to the FTC guidelines, if someone is being rewarded to promote a product, viewers must be clearly informed — for example, many influencers disclose these financial ties by adding hashtags such as #ad or #sponsored. Sometimes online stars even spell it out in their own voice, following the FTC instructions that say: “A simple disclosure like ‘Company X gave me this product to try….’ will usually be effective.”

But not everyone comes clean with their followers about why they are praising a product. And in a twist that demonstrates the complexities of the world of influencers and money, some Instagrammers and YouTubers are even faking business relationships with companies to try to boost their reputation by showing that they have enough of a following to be seen as influential.

So that’s even more reason to wonder about motives when seeing plugs for products online. It comes down to the adage “caveat emptor” (“buyer beware”). Or maybe just don’t buy.

Behind every sockpuppet is a person trying to hide

Let’s say you’re out to buy a pair of shoes, and you’re checking reviews.

“So many compliments. Thanks!”

“Best purchase I’ve made in my life.”

People seem to love these shoes … so, great! You’ll buy them!

Now say you’re out to form an opinion, and you’re checking comments.

“Brilliant points you’ve made. Thanks.”

“I couldn’t agree more with everything you’ve said.”

People seem to love this writer’s ideas … so great! You’ll buy these opinions!

Whether it’s a product or an idea that people are commenting on, if the reviews are excessively for or against, you might have entered the world of sockpuppetry.

A sockpuppet is a false online name and profile created to hide the author’s identity, usually because of personal, political or financial ties to whatever is being discussed or reviewed. Sockpuppets try to sway people’s minds for profits, for petty ego — or for much worse.

As an example, an author used several fake names to post positive reviews on Amazon about his own book in the hope that this praise would result in more sales. Authors have also used made-up identities to give bad reviews to competitors’ books.

Worse examples of sockpuppets are when those in power encourage violence by passing themselves off as regular citizens, as happened in Myanmar in 2018. In that situation, senior military officials used fake names to create pages on Facebook, then used other false identities to fill those pages with comments intended to fuel hate.

Sockpuppets also played a malign role in the U.S. presidential election in 2016.

Even when it doesn’t threaten institutions, sockpuppetry is disruptive. A 2017 New Scientist article calls it “the scourge of online discussion” that “can dominate comment forums” and spread lies, especially when one user controls multiple accounts.

Help might be on the way: Computer scientists are trying to create ways that platform moderators and administrators can spot and block sockpuppets. Until then, the best way for users to ward them off is with common sense, turning to trusted resources and credible reviewers to gather facts to decide whether to buy the shoes … or someone’s argument.

When encountering information, be wary, but open

“‘Skeptics’ are healthy for journalism, but ‘cynics’ are not,” Merrill Perlman wrote in her Columbia Journalism Review column, Language Corner. The same could be said for consumers of news: skeptics, good; cynics, bad.

On first look at the origins of these words, they seem different: “Skeptic,” Perlman wrote, is derived from a Greek word meaning “thoughtful” or “questioning”; a “cynic” — which evolved from the name of a group of philosophers in ancient Athens — simply disbelieves everything.

But in practice, especially in an information environment seemingly filled with attempts to deceive, one might lurch over the dividing line between being skeptical and being cynical.

Indeed, that’s a problem, according to a study of college students’ news consumption habits. How Students Engage With News: Five Takeaways for Educators, Journalists, and Librarians — commissioned by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and published in October 2018 by Project Information Literacy, a nonprofit research institute — found that more than a third (36%) of the students said that the threat of “fake news” had made them distrust the credibility of any news.

John Wihbey, an assistant professor of journalism and media innovation at Northeastern University and one of the study’s researchers, pointed out the balancing act: “On the one side, you’re arming young news consumers to be aware of the source of information. On the other side, we don’t want to raise a generation not to believe in the power of well-reported, well-researched, well-sourced news.”

News literacy helps, say news experts, both in the mental habits it builds and in the tools it provides.

Mike Caulfield, director of blended and networked learning at Washington State University at Vancouver, responded to the Project Information Literacy study in an interview with the Poynter Institute, a journalism education nonprofit. Students, he said, might seem to have “cynical postures. But those cynical postures are based on being overwhelmed, and once you give them quick tools they can apply, the cynicism goes away.”

In remarks to students in March 2018, Poynter’s Roy Peter Clark was both philosophical and practical, calling “skepticism” and “cynicism” frames of mind. Skeptics seek the truth, Clark said; their frame of mind is to seek facts to support or refute information. Cynics leap to moral judgments; their frame of mind is to skip facts entirely. His advice: “Be a skeptic, not a cynic.”

Smart news consumers know when they’re being pitched

Advertising has long been a form of entertainment: Consider the fact that the ads broadcast during the Super Bowl are celebrated as much as the football game itself, with news articles devoted solely to compiling and reviewing them. People know that between plays and before and after the halftime show, companies will be trying to sell them things; in some years, the ads have been more popular than the game.

What is not as much fun is when we believe we are seeing a neutral report, only to suddenly realize that we are seeing an ad. The only thing worse than that is to not realize that someone is trying to sell you something.

The array of ads-that-don’t-seem-like-ads include native advertising (also called “sponsored content”) and social media posts by “influencers,” those popular online personalities whose motives for talking up a product might not be obvious (not everyone knows that #sp in a list of hashtags on a post means “sponsored” or, more clearly, “I’m being paid to promote this”).

Ads are becoming more creative in hiding their true nature because marketers face the same challenges as the news industry: We live in a world of information overload, short attention spans and rapidly evolving technology. As a result, businesses are getting savvier about selling their goods.

That makes it even more important for readers, viewers and listeners to understand if what they stumble across is designed to inform, or if its ultimate goal is to sell a product.

Be warned by the words of Danny McBride, an actor who appeared in a series of ads that were part of a campaign whose aim was initially unclear: “People were confused and wondering what it was. They were talking and speculating. Ultimately, that’s what a good ad is supposed to do.”

Don’t be confused by what might be a good ad. The smart news consumers know when someone is trying to sell them a product.

Before investing time in the story, investigate the source

Plenty of people have go-to news sources. But what happens when you stumble across a site that looks legitimate? What if you’ve never heard of it? How do you know if the news organization behind it is real or a spoof? How can you tell whether it has financial or political ties that will tilt its coverage?

The fastest way to determine if a site might not be an honest purveyor of news is to look at the web address. People trying to make a quick buck often buy domains similar to those of well-known news organizations and add .co to the end, or use neutral names that hide their shady nature.

Equally important is the way the site describes itself and its work. Look for words that imply a nonpartisan search for facts. For example, The Washington Post introduces its “Policies and Standards” (in the About Us section) with its mission statement. (“The first mission of a newspaper is to tell the truth as nearly as the truth may be ascertained.”) The investigative site ProPublica calls itself “an independent, nonprofit newsroom.”

Don’t let kidders kid you

By contrast, click the “About” tab on The Onion, where it calls itself “the world’s leading news publication.” It also makes comically exaggerated claims that should tip you off that it’s not a real news site. Consider this gem. “Rising from its humble beginnings as a print newspaper in 1756, The Onion now enjoys a daily readership of 4.3 trillion and has grown into the single most powerful and influential organization in human history.”

You can learn more about this serious topic and related issues in the podcast episode These Kids Don’t Play: Anxiety About Bias in the Media. Part of the podcast series Inside the Chrysalis, it features NLP’s Senior Vice President of Education Peter Adams.

And remember, even journalists have fallen for hoax sites — proving it’s always good to apply news literacy skills to what you see and hear.

News Lit Tip

Don’t be blown away by the ‘straw man’ fallacy

Straw: It’s lightweight, it’s insubstantial and it easily blows away.

That’s also true of the type of argument known as the “straw man” fallacy — but only if you

recognize it.

This lapse in logic can occur in a discussion when one person responds not to the point being

made, but to a new point created by simplifying or exaggerating something that another person

said.

This shift in language can be subtle, though. That’s why it’s easy to be tricked with a straw man

argument, especially when the topic being discussed is controversial — when people are jumpy,

and tempers are ready to flare.

You’ll find examples across the political spectrum:

- When someone expresses support for restricting the sale of assault weapons, a straw

man argument would ask “Why do you want to take away everyone’s guns?” - When someone notes that regulations to counter the effects of climate change might be

burdensome on businesses, a straw man argument would ask “Why are you denying

that climate change exists?”

In both cases, the straw man argument ignores the other speaker’s point, and instead trashes a statement that was never made.

The straw man fallacy appears often in political debates, when speakers are focused more on

impressing and persuading the audience than on changing their opponent’s view. To avoid

being taken in, listen closely: Is someone repeating the point being made and addressing it, or

has the subject simply been changed?

Here’s something you can do to avoid having to flail against a straw man when discussing hot

topics: Choose to repeat what exactly was said, and make sure that others agree with your

interpretation, before attempting to respond. That has the advantage of slowing and calming the

conversation as well.

And that’s better than building and propping up points of view that are built on straw.

This apple is not an orange! And other false equivalences

“This is not equal to that” is how one writer summarizes the logical fallacy known as false equivalence.

As the name suggests, false equivalence is a cognitive bias by which events, ideas or situations are compared as if they are the same when the differences are substantial. Those differences can be either in quantity or quality. This form of flawed reasoning can sneak into conversations, and it can show up in news coverage, too.

Here’s an example of false equivalence:

Yes, Mr. Smith is a serial embezzler, but Mr. Jones once littered in the park. Both are criminals!

This is a qualitative difference in which two acts are compared as if they’re equivalent. While each could be considered dishonorable, one clearly is worse than the other.

Here’s another example, this one from Checkology’s Arguments & Evidence lesson. This lesson offers a fictional situation in which a boy posts a photo of a test question on social media, and as a result, the testing company decides to invalidate all students’ tests. A student complains:

A teacher doesn’t punish a whole class when one student cheats! Why should this testing company punish every kid in America?!

While there is an apparent similarity between two things, important differences are ignored. That argument doesn’t compare apples to apples. A more reasonable comparison would be a teacher invalidating a class test because one student shared a test question with the entire class.

News reports can be guilty of false equivalence when two sides of an issue are cited as if they were equal. Consider climate change. Today, scientific consensus is that the planet is warming, and that human activities are the cause. Yet, as a 2014 column in Columbia Journalism Review points out, sometimes “false balance” has journalists “presenting the science as something still under debate.”

Raw information needs context for healthy consumption

“‘Raw data’ is both an oxymoron and a bad idea; to the contrary, data should be cooked with care.”

In this sentence from his book Memory Practices in the Sciences, Geoffrey Bowker, a professor of informatics at the University of California, Irvine, is pointing out that, like uncooked food, raw information can be dangerous unless properly prepared. The key ingredient that needs to be added: context.

What is raw data? It’s the product of security cameras that unceasingly record what’s going on in front of the lens; it is in government reports filled with numbers and percentages; it’s what is shared online from cellphones that people use to record an event. Those are examples of raw information, unedited and unprepared.

Journalists are among those turning raw information into comprehensive reports — by verifying it, adding context and considering complexities that make the accounts whole. But not all raw data ends up this way, so it’s important for all of us to understand if what we’re seeing is raw or if it has been properly prepared for consumption.

Take the scene that played out on the National Mall in Washington in January 2019.

A short video shot near the Lincoln Memorial and shared widely online showed a high school student from Kentucky and a Native American activist facing each other directly. The initial interpretation described it as a standoff and contended that fellow students were behaving in disrespectful, even racist ways toward the activist.

Even the organizers of the event that brought the students to Washington at first apologized for the “reprehensible behavior shown in the video” in a tweet that was subsequently deleted.

But that information was raw. That initial interpretation was woefully incomplete, and gave way later to a more comprehensive picture based on others’ videos and interviews with bystanders and witnesses.

And that’s just one example. Every day, every minute, the public is assailed by raw information, whether it’s a snippet of cellphone video posted online or a report whose figures haven’t been put in context. It might take time, but don’t eat consume those data uncooked: Wait for the context to be added to make for a properly prepared report.

One thing leads to another, and sometimes that’s wrong

Picture yourself at the top of a grassy hill. You’re enjoying the view, but it’s time to head home. “Stop!” someone near you calls out. “Don’t move. People fall, and if you take a few steps, you’ll end up hurt.”

That is a basic description (and splendid imagery) for the logical fallacy known as the slippery slope argument, which starts with an initial assumption and then follows a crooked path of ideas to an often illogical conclusion. Like other logical fallacies, slippery slope arguments reflect a lapse in critical-thinking skills.

Perhaps, as you stand there atop the hill considering that advice, you think: What if it’s true? The problem in logic lies in the assumption that one step will inevitably lead to another incremental step, and another, and another, ending up in a bad result. As RationalWiki puts it: “A leads to B which leads to C which leads to D which leads E which leads to zebras having relations with elephants.“

Here are a couple of examples of a slippery slope argument: “We have to stop the tuition increase! The next thing you know, they’ll be charging $40,000 a semester!” And: “You can never give anyone a break. If you do, they’ll walk all over you.”

Such arguments are not always fallacious; those that lay out precisely the causal link between one step and the next might be correct. But the cause of how one step leads to the other needs to be based in fact.

An article in Lifehacker defines an assortment of logical fallacies and suggests how to handle this one: “To avoid slippery slopes, think about how likely the scenario is and if it could be supported by facts and statistics.”

So head down the grassy slope without falling for the illogical leap that says such walks always lead to injury.

Ad hominem attacks go for the jugular instead of the facts

I’ve never seen you in church. Why would I believe you when you say you’re a Christian?

If you think those two statements don’t quite follow, you’re right. This is an example of a logical fallacy known as an ad hominem attack. The Latin phrase (“to the person”) is used to describe an attack on the character, motives or other attributes of a person making an argument, rather than on the argument itself.

It’s easy to be knocked off balance by an ad hominem attack, but don’t be. An observation raised about you or your choices means that the other person is, simply put, changing the subject.

Just as you can, unfortunately, criticize people in many different ways, you can divide ad hominem attacks into several categories. Here’s an overview of some types of ad hominem arguments, with examples from An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments:

- Abusive ad hominem attacks address the person and not the idea: You’re not a historian; why don’t you stick to your own field.

- Circumstantial attacks change the subject by saying that the person holds that opinion only because it will help them in some way: You don’t really care about lowering crime in the city, you just want people to vote for you.

- Tu quoque, in Latin, means “you too”: John says: “This man is wrong because he has no integrity; just ask him why he was fired from his last job.” To which Jack replies: “How about we talk about the fat bonus you took home last year despite half your company being downsized.” Irrelevant charges of hypocrisy fit here as well (“You’re overweight, so you can’t argue that everyone should exercise”).

When someone makes an ad hominem attack, don’t take the bait by taking it personally! Turn the argument back to its relevant points.

Posts that troll are designed to irritate, not educate

If you’re active in any way on the internet, you’ve probably heard this: “Don’t feed the trolls.” Also: Don’t let the trolls feed off you — or your anger. When something online makes you hot under the collar, it’s possible that someone is aiming to irritate, rather than make a well-reasoned point.

“Don’t Feed the Trolls” is also the title of a 2019 report (PDF) from the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH), a nongovernmental organization based in London.

“Political trolls are skilled and determined propagandists, promulgating harmful extremist beliefs, like sectarianism, racism and religious intolerance, using abuse and mockery,” CCDH CEO Imran Ahmed and advisory board chair Linda Papadopoulos write in the report — which also cites Whitney Phillips, the author of This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things, as noting that trolls ”self-define as people who believe ‘nothing should be taken seriously’ and ‘like to disrupt stupid conversations on the Internet’ for ‘lulz’: ‘amusement derived from another person’s anger.’”

So what’s a civil citizen of the internet to do when faced with a comment that seems outrageous?

First: Don’t let it get to you! If what you see makes you angry, the first step is to not engage — don’t debate, don’t share.

Although “Don’t Feed the Trolls” is aimed at high-profile figures and organizations, it provides useful advice, saying that most people fall into the trolls’ trap: “We act counterproductively, engaging trolls, debating them, believing this is a battle of ideas. In fact, the trolls are playing a quite different game. They don’t want to ‘win’ or ‘lose’ an argument; they just want their ideas to be heard by as many potential converts as possible.”

Use your news literacy skills to take apart the information. Don’t let the trolls hijack your mind.

Beware the bots

“On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog,” one canine tells another in one of The New Yorker’s most famous cartoons. That was 1993. Today, the saying could be: “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a bot” — except for those exceptional users who are news-literate and savvy to the ways of bots. (But watch out. Bots can be sneaky.)

Not all bots are awful. They are programs that carry out automatic tasks: the worker bees of the internet, as a piece in The Atlantic put it. Some refresh your Facebook feed. When you visit an online merchant and a tiny figure pops up in the corner of your screen (hi there, chatbot!) asking how he or she … uh, it … can help, that’s a bot.

But beware of bots gone bad. In 2018, those gremlins made up some 20% of web traffic, according to a report by Distil Networks, a cybersecurity company. “Bad bots” are used to publish and spread misinformation. A 2018 study by researchers at the University of Southern California referred to the scourge as “social hacking,” as bots spread “negative content aimed at polarizing highly influential human users to exacerbate social conflict.”

Data for Democracy (“a worldwide community of passionate volunteers working together to promote trust and understanding in data and technology”) presents pointers for how to know what’s a bot, so you can avoid being socially hacked. Among traits to look out for are accounts that:

- Post at all hours of the day and night. “Continual round-the-clock activity is a sure-fire sign of somemeasure of automation.”

- Retweet a lot. “Accounts that are exclusively retweets (or pretty close) aren’t always bots, but if they exhibit some of the other traits here, there’s a good chance they are.”

- Use identical language as others. Coordinated content is the sign of a campaign to sow disinformation.

If it posts constantly like a bot, retweets like a bot and uses language like a bot … it probably is a bot. Don’t be caught by it, and don’t spread its messages to others!

Don’t bite: It might be engagement bait

Facebook cracked down on engagement bait in December 2017, defining as spam these “posts that goad people into interacting, through likes, shares, comments, and other actions, in order to artificially boost engagement and get greater reach.”

Tellingly, the information is on a section of the platform that’s directed at businesses, for it is businesses that were — and are — the most likely to attempt to make posts and pages seem more popular. That apparently popularity, in turn, puts those posts and pages in the news feeds of more people.

As with bait used to snag other unwitting animals (putting a hunk of hamburger in a room to trap Fido, or spritzing catnip spray to get Felix in the carrier), the bait created to snag humans online varies, but the motive rarely does: More eyes, after all, mean more money. (Sometimes it’s used for political effect, such as when a little-known far-right party in the United Kingdom suddenly developed a huge following.)

Facebook puts these types of posts and pages into five categories: react-baiting (post an emoticon that fits your response!); comment-baiting (say yes or no!); share-baiting (share this!); tag-baiting (tag a friend who would like this!); and vote-baiting (vote for idea A or idea B!).

In addition, getting hooked on engagement bait may put your private information at risk. As the fact-checking site Snopes points out, some of these posts and pages urge you to follow a link that takes you to a site that appears to represent a business giving away products. You might be asked to share such “offers” — and you might also be asked to provide personal information, including credit card details and more.

Snopes notes another danger: “Like-bait posts also often swap out their original content for scams once they have garnered enough likes.”

In short: Don’t “like” something if you don’t know its provenance. And sharing is best when done with friends.

Like reporting, science is a process of uncovering facts

Is caffeine good for you, or is it harmful?

You can find studies that answer “yes” (and “no”) to both questions.

This sums up one truth about scientific findings: They aren’t usually black and white. And that ambiguous reality is not always reflected in the news media, where reports on scientific findings often do not show the complexities involved.

A 2018 study aimed at reporters (and written by Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania) can help the general public understand how to read science.

Much like reporting, science is an investigative process replete with false starts, dead ends and incremental findings. After all, the scientific method itself consists of twists and turns, starting with making an observation or observations, then forming and testing hypotheses, and finally reproducing the findings (repeatedly).

Science as it appears in the headlines might obscure those subtleties. Coverage that the general public sees is too often broken into one of three storylines, according to Jamieson:

- “Discovery,” an angle on coverage that implies discoveries are “breakthroughs.”

- “Counterfeit quests,” in which bad people make up data to support unfounded conclusions.

- The “science is broken” storyline, which suggests that there’s a systemic problem in science.

All three have in common the mistaken idea that science is clear-cut, rather than a process of discovery. Which means that the studies that say caffeine is great for you might be as verifiably correct as the ones pointing out its health flaws.

As Jamieson said in an interview about her study, “Science continues to build on itself. An article about discovery should also note the unanswered question. When one finding is replaced by a better one, the public needs to understand that a finding is a step on a path that over time leads to more reliable knowledge.”

Wise news consumers should apply their own scientific method to early reports about scientific findings, knowing that gaps in knowledge will soon be filled and might lead to updated results.

Results reported in Jamieson’s essay “Crisis or self-correction: Rethinking media narratives about the well-being of science” were based on researchers’ combing through 165 science articles in six national publications from April 2015 through December 2017. It was published in the March 13, 2018, issue of the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences of the United States of America.

The psychology of anger, and news literacy

While many dither about the meaning (or lack of meaning) of the phrase “fake news,” for the purposes of her 2018 paper “Both Facts and Feelings: Emotion and News Literacy,” Susan Currie Sivek is clear: It “truly has primarily a manipulative intent and may deviate from factual accuracy to achieve that goal.”

“Unlike the objective tone sought by most mainstream journalists,” she writes, “creators of fake news typically seek to strike an emotional chord that will spur audiences to react and to share the fake content.”

Sivek, chair of the journalism and media studies department at Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon, then lays out her concern: Technology is now a part of the scourge of people trying to appeal to emotions rather than intellect, as algorithms and apps use our personal data to recognize (and respond to) what we’re feeling and when we’re feeling it. She says: “Our emotional capacities appear freshly vulnerable to external influence in this new technological context.”

She wants us to recognize why, and how, we’re feeling angry — and to know how to handle it.

When we go online, she writes, two issues arise: We’re increasingly observed by “emotion analytics” — the hardware and software on our devices that can respond to our emotional states — and, as ever, we take mental shortcuts to make decisions.

One way to sharpen critical thinking, of course, is by improving news literacy skills. Thanks to the News Literacy Project’s efforts, and others’, she notes, growing numbers of readers, viewers and listeners are at least aware of the many clever ways that trolls, extreme partisan groups, internet subcultures and even — in a more benign way — advertisers are out to hijack our attention and emotions.

Her suggestions? Slow down before sharing, and learn the details of the devices (including digital home assistants) that are collecting information about you. But above all, she advises, be mindful of where you’re encountering news and how you’re reacting to it: That can go a long way to keep you from being motivated by hot emotions — especially when those emotions are exactly what the “fake news” purveyors want.

Doctored images put words in people’s mouths (and on their shirts)

“This Shirt Says It All!” one Twitter user wrote in October 2017 about a viral photo of NBA star LeBron James in a graphic T-shirt.

Well, no, in fact, it didn’t. The message on the shirt had been manipulated. What is accurate was the headline on the PunditFact article that fact-checked the image: “Fake photo changes social message on LeBron James’ t-shirt.”

Both messages, altered and original, were commentaries about perceptions of the treatment of Black Americans. The altered message said, “We march, y’all mad. We sit down, y’all mad. We speak up, y’all mad. We die, y’all silent.” The original message (included in the PunditFact fact-check) was “I can’t breathe” — the final words of Eric Garner, a New York City man who died as the result of an illegal police chokehold in July 2014.

Words can be seamlessly changed in other photos, too. Take the photo of cosmologist Carl Sagan holding a sign that warned against placing billboards in space. If that sounds ridiculous, your news literacy Spidey sense is right: The sign Sagan held in unaltered photos was a pictorial “message from Earth” included in spacecraft sent out in the early 1970s.

And according to Snopes, the most recent dissemination of the anti-billboards image, which first gained traction around 2010, was a statement by someone (not Sagan, who died in 1996) who saw the 2018 launch of the Falcon Heavy rocket as a commercial ploy by its funder, Elon Musk. (That said, Sagan did describe as “an abomination” a 1993 plan by a company in Roswell, Georgia, to place a giant billboard in orbit in time for the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta.)

Digitally replacing letters in photos online is, unfortunately, easy to do — the equivalent of putting words in their mouths (or on their posters or shirts). Fortunately, being aware of the fact that such manipulation is possible means that you might question the accuracy of photos. When in doubt, do a reverse image search. And always consider the credibility of your sources!

Believe it or not! The images are not real

A smiling elephant stands on his back legs under a waterfall, blissfully enjoying being splashed. The image on Twitter has a simple caption: “Happy Elephant.”

This is an animatronic elephant from the Jungle Cruise ride at Disney World’s Magic Kingdom in Florida. https://t.co/7rL2nINw3W

— PicPedant (@PicPedant) October 16, 2019

And the caption on the extraordinary image of the polar lights is just “Aurora over Northern Norway.”

Both images take your breath away. But before you swoon, consider this: As breathtaking as nature can be, “amazing” photos found online are often fakes or presented out of context.

That happy elephant? It’s really an animatronic contraption from a ride at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom in Florida. And the vision of lights — implied to be an untouched photo of the aurora borealis — is a composition of three separate photos.

That information comes from Paulo Ordoveza, who on his Twitter profile calls himself “Punctilious internet killjoy at the forefront of the New Debunkonomy.” As @PicPedant, he pokes holes in a lot of the stuff people pass off as real, untouched images from nature or life.

Janne Ahlberg is another internet sleuth who unmasks fake photos online. Followers of his @hoaxeye account (profile description: “Hoax fighter and fact finder. Main tools: reverse image search and coffee”) will see photos and narratives debunked, like the one that has a frog using a leaf as an umbrella (not really).

For 10 examples of how real photo manipulation can look like real life, take a look at these examples, which include protest crowds at events unrelated to the information in the caption and people side by side in an image even though they never were together in real life.

When you see an “amazing” image, make sure your sense of wonder is accompanied by real questions. Here’s what a blog post on Pixsy, a website where photographers can track the unauthorized use of their images online, suggests:

- Use reverse image search tools, such as Pixsy, to find out where the image has come from, and how it’s been changed.

- Try running a description of the image through various stock photography services. This is often the source when a photo claims to show something it actually doesn’t.

- Do a phrase search on Twitter, Reddit etc. to see when jokes or captions have been recycled.

Rumor has it … and rumor has it again … and again

Like the bad germs they are, viral rumors come to life, then die down, then flare anew when the people or issues they’re about are back in the news.

To understand how and why, consider what a virus is, and also what makes for a rumor.

“Viral,” of course, is based on “virus,” a highly contagious microscopic parasite.

Now consider the psychology of rumors. Research shows that several factors play into their dissemination: When there is uncertainty. When we feel anxiety. When the information is relevant to something important.

Combine the viral aspect (a germ that spreads quickly) and the psychology aspect (a nugget of information that fascinates) with the internet, and you have a recipe for a super-virus.

One example is a false and oft-repeated rumor about actor Denzel Washington. Contrary to social posts shared widely, Washington did not publicly back then-candidate Donald Trump for president in the 2016 election. The origins of the rumor are murky (a site later found to be headquartered in India was among the first to post the made-up information), but the repeat flare-ups of the meme include clues to its mutations: After 2016, it popped up again in February 2018, when Washington was in the headlines for his Oscar nomination. Then months later, when musician Kanye West — another prominent African American — spoke in support of Trump, the Washington-Trump rumor-meme spread around the internet yet again.

Another example of how viral rumors come back and back: A caption and widely shared photo of a couple (with the woman in blackface) erroneously identified the couple as Bill and Hillary Clinton. The meme circulated in 2016 during Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, then popped up again in February 2019 amid controversies involving blackface and a number of politicians, including Florida Secretary of State Michael Ertel, Florida state legislator Anthony Sabatini, and two elected officials in Virginia, Gov. Ralph Northam and Attorney General Mark Herring.

Controversial topics don’t go away; neither do viral rumors about them. They might lie dormant for months, only to re-emerge — and perhaps spread even more widely than before — when a germ of the controversy again is in the news.