More Info

Alana Frick’s students in Santiago, Chile, apply what they learn from Checkology lessons to help them navigate misinformation regarding widespread protests and demonstrations occurring in their country.

Photo courtesy of Alana Frick

Events in Chile put students’ news literacy skills to the test

Under normal circumstances, Alana Frick teaches NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom as a stand-alone media literacy unit sometime between April and June.

But circumstances have been anything but normal for the eighth-grade humanities teacher in Santiago, Chile. When public demonstrations engulfed the country in October, Frick and her colleagues at The International School Nido de Aguilas realized that they couldn’t wait.

“We said, ‘We have to do this.’ We were receiving so much misinformation and false information. This is the perfect opportunity.”

“With all the civil unrest in Chile, and the misinformation circulating, we knew that we needed to implement it in our teaching immediately,” she said.

Life disrupted

The widespread protests, sparked by a planned fare increase for the Santiago subway system, tapped public anger over the nation’s rising cost of living and income inequality. As thousands took to the streets and demonstrations turned violent, misinformation flourished. In late October, citing student safety, the government closed schools in Santiago and elsewhere for a week.

Because students can access Checkology — and complete lessons on their own — anywhere they have an internet connection, Frick and her fellow humanities teachers quickly revamped their lesson plans.

“With everything going on, we were messaging each other the first day we were out of school,” she recalled. “We said, ‘We have to do this.’ We were receiving so much misinformation and false information. This is the perfect opportunity to get this out to our kids. They can learn it at home.”

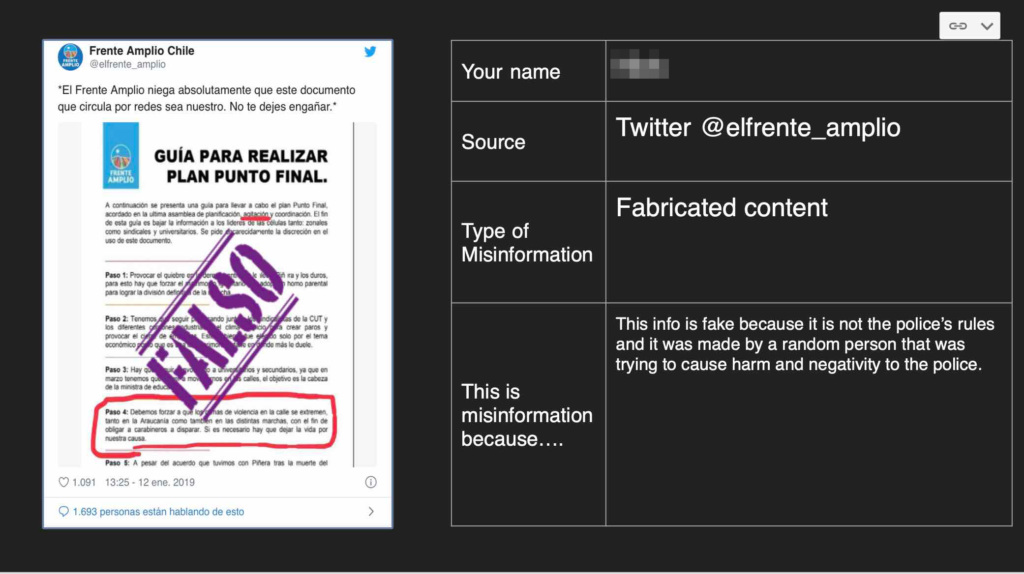

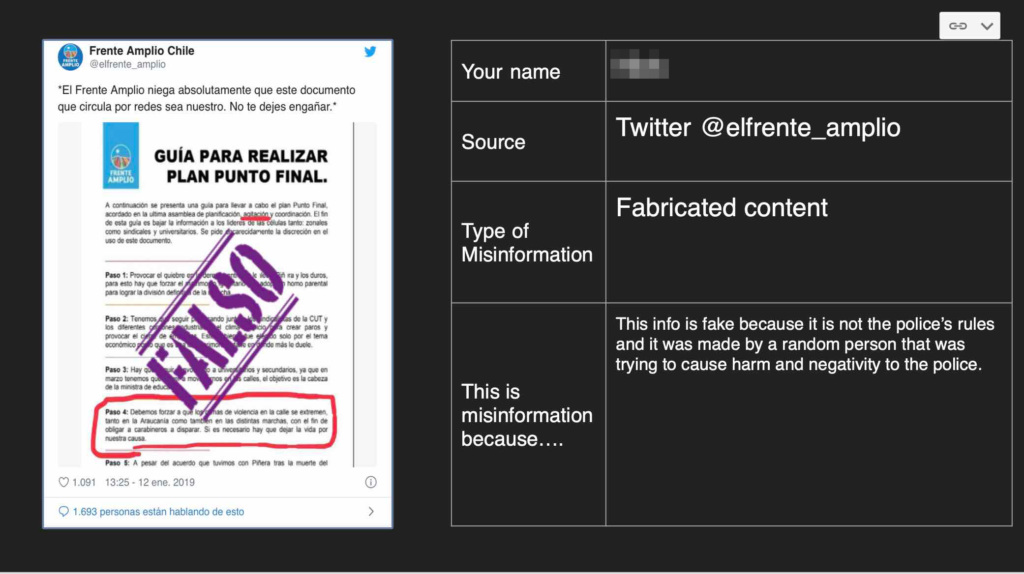

When civil unrest closed school for a week in October, Frick’s students worked on assignments from home, sharing examples of misinformation they encountered in an online slide presentation.

Challenges and opportunities

The closing of school amid the external chaos did present challenges. “It was disruptive to our routine,” said Frick, who has taught at the school for five years. There was, she said, “a feeling of uncertainty and fear. But there was a schoolwide effort to do remote teaching, making sure we don’t fall too far behind.”

The events did provide a real-world laboratory for teaching news literacy. “Out of all the lessons that we have taught, I truly think the lesson on misinformation has been the most impactful,” she said.

“They were really bothered that people were purposely manipulating content and sharing what wasn’t true.”

Mining what was circulating online about the civil unrest, the teachers built a slide presentation template for students to upload examples of misinformation they found on social media or news sites. For each, they were asked to categorize the type of misinformation, identify the source of the content and describe why it was misinformation.

“I think what has been most surprising to them is how much false information was circulating,” she said, adding that her students “were horrified at the manipulated content. I think they were really bothered that people were purposely manipulating content and sharing what wasn’t true.”

Putting their skills to work

Once they began applying the skills learned from Checkology, the students were better able to verify sources and double-check the content flooding their social media feeds, Frick said. Several students even taught news literacy skills to their parents.

For example, one of Frick’s students told her that his mother showed him a news account about the protests that she had found on social media. Looking at it, he noticed that the account had not been verified by the platform’s administrators, and he immediately questioned its validity. He showed his mother the differences between verified and counterfeit accounts. “He told me he then sat down with her and went through the entire module, and he walked her through how to identify misinformation,” she said.

Despite the ongoing civil unrest, the students have returned to school, where they continue to flag misinformation or propaganda they encounter online and share their discoveries with the class. This exercise isn’t just purely academic; it’s practically applicable.

“In a time where information and correct information can be a matter of serious safety, Checkology has helped my students become educated in matters of media literacy and misinformation,” Frick said.