|

Top picks

|

| Former conspiracy theorists say that conspiracies provided meaning when they felt empty. Illustration credit: Liftwood/Shutterstock. |

|

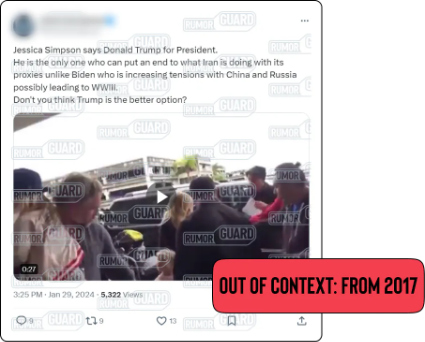

Millions of people follow conspiracy theories online, but not everyone finds their way out like Ramona, a Tennessee woman who quit following them and is now a fifth-grade teacher. She fell down the rabbit hole during the coronavirus pandemic, when she moved in with her boyfriend, Don, who held strong conspiratorial beliefs. In an interview with The Associated Press (link warning: domestic violence), Ramona, 23, said some of Don’s unfounded beliefs — that the pandemic was orchestrated, vaccines were unsafe and Armageddon was coming — sounded plausible amid the fear and confusion of the pandemic.

Eventually, “doomscrolling” through conspiratorial content online about topics like satanic sacrifices increased Ramona’s anxiety. After taking a break from social media, she stepped away from conspiratorial circles for good, broke up with Don, got vaccinated against COVID-19 and went back to school to become a teacher.

- Note: This story is part of an Associated Press series on the role of conspiracy theories in American society.

- Discuss: What attracted Ramona to conspiracy theories? How did she find community in QAnon circles? Why did it also make her feel isolated? How did Ramona dig herself out of the rabbit hole? Why do some people fall for conspiracy theories?

- Idea: Watch this five-minute AP video featuring experts on conspiracy theories, a former conspiracy theorist and a self-proclaimed conspiracy “questioner.” Discuss the video with students. What is the “Ikea effect” explained by academic Francesca Tripodi? How is this technique used to spread conspiratorial thinking?

- Resources:

- Related:

|

|

Advertisers and online influencers have a growing, new revenue stream: AI-generated product placements in TikTok and YouTube videos. Realistic-looking products like soda cans and shampoo bottles are seamlessly added into social media videos that aren’t necessarily formatted like standard ads — reaching younger viewers and offering a look at how AI could impact the future of advertising. Product placements in the U.S. are estimated to be a nearly $23 billion industry.

- Discuss: How can you tell if there’s product placement in a TV show, movie or social media post? How does product placement compare with other forms of advertising? How should sponsored content and ads — including AI-generated product placement — be labeled or disclosed?

- Resources: “Branded Content” and “InfoZones” (Checkology virtual classroom).

- Related: “Hulu Shows Jarring Anti-Hamas Ad Likely Generated With AI” (Amanda Hoover, Wired).

|

|

Amid the stress of extreme weather events, misinformation runs rampant. It happened in California as the state was hit with heavy rain and flooding, and a viral tweet by an emergency preparedness enthusiast — not a meteorologist or weather expert — made a false warning of a catastrophic megaflood. The post reached millions of X users and prompted responses from the National Weather Service and climate scientists, who debunked the rumor and directed people to more credible sources of weather information. Meteorologists and emergency officials say they are increasingly faced with how to respond to viral falsehoods and disinformation.

- Discuss: Why does misinformation spread during extreme weather events? How do bad actors capitalize on natural disasters to gain cheap likes and shares? How can you tell if a source of weather information is credible? How would you evaluate a science-based claim on social media?

- Resources:

- Related:

|

|