Science literacy tackles the element of misinformation in the news

The periodic table of elements provides a systematic structure that can be used to predict the properties of elements, including the ability to form compounds and drive chemical reactions. It brings organization and reliability to the chemical landscape.

Unfortunately, there is no periodic table of information. That leaves us with an information landscape that is anything but organized, with an abundance of misinformation — the element that can spark harmful reactions, and actions.

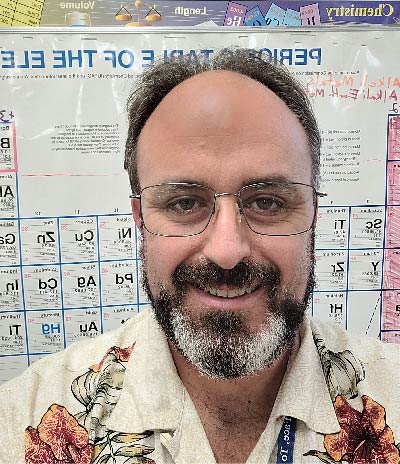

“With the amount of misinformation being thrown around, I felt it was my responsibility to make them better consumers of information,” said Albrink, who teaches at Mason County High School in Maysville, Kentucky. “We are getting this mindset of polarization [that] science isn’t real. That was a big red flag.”

Engaging students during remote learning

Like schools all over the country, Mason County High closed when the pandemic hit. Albrink needed to find resources that would engage his students and allow them to work independently in a virtual learning environment. He found what he needed in Checkology®, the News Literacy Project’s e-learning platform, and The Sift®, its weekly newsletter for educators.

“This seemed right up my alley, a way to teach good research skills and methodology,” said. Albrink, an educator with 17 years of experience who teaches mainly juniors and sophomores. “I felt it was important.”

Albrink used items featured in The Sift’s Viral Rumor Rundown to teach his students how to avoid being fooled by popular memes and provocative posts. “We’d do reverse image searches, talk through how to spot fake accounts on social media, and to take it all with a grain of salt,” he said.

Using real-life examples to teach foundational concepts of science literacy captured his students’ attention — and surprised them. “They’re just kind of amazed at how much falsehood is out there floating around.”

Making connections with science literacy

Albrink used the Checkology lesson “InfoZones” to help his students get a better grasp of the types of content they were seeing. Students learned how to differentiate among types of information — news, opinion, advertising, entertainment, propaganda and raw information. They tested their skills with examples in Checkology’s interactive Check Center and then independently applied the concepts they learned to news articles, judging credibility and putting information in context.

Their exploration of mask-related myths provided Albrink with an opportunity to connect the news directly to chemistry lessons. He taught them about the size of molecules and how being able to smell odors while wearing a mask does not mean masks are ineffective. These teachable moments from current events resonated. “It’s affecting their lives directly. Otherwise, if they can’t make a connection, it’s hard to engage,” he noted.

Teaching science literacy made him realize that kids often don’t have the essential skills to discern good information from bad and were being taken advantage of by those who create and share falsehoods. “Hopefully, I opened their eyes to be leery of what people say. If I can provide a layer of insulation, I feel like I succeeded with them.”

Albrink wishes that he had encountered news literacy resources and applied them to his science classes sooner. Now that he has, he will continue to weave science literacy into his classroom lessons. “To progress as a professional, I think this is the direction I want to go,” he said.