Spotting social media ‘bad actors’

No, we’re not talking about the nominees for a Razzie — a parody award “celebrating” the worst in film. In the world of misinformation, a “bad actor” is a type of social media account that spreads misinformation and often causes confrontation. Examples of these accounts include trolls, bots and sockpuppets, and all of them can make it difficult to identify legitimate sources of political discourse.

One recent example comes from the tense interaction at the Lincoln Memorial on Jan. 18 involving students from Kentucky’s Covington Catholic High School, a group of Black Hebrew Israelites and a Native American elder with a drum. Though many Twitter accounts had videos of the incident, this short clip and comment by @2020fight (the account has since been deleted) ignited a viral controversy:

This tweet shaped much of the discussion that soon followed, including the initial news reports about the confrontation. (For an excellent rundown, see the Jan. 28 issue of The Sift, our weekly newsletter for educators.)

But as more details and context emerged, reporters — and others — took a closer look at the @2020fight Twitter account. (See, for example, this Twitter thread from Ben Nimmo of the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensics Research Lab.) The account, created in December 2016, contained a highly partisan (and likely manipulated and, to many, offensive) political image in its header, described the user as a “Teacher and Advocate” from California and included a link to the site Teachers Pay Teachers, an online marketplace for teacher-created educational materials. But the profile photo wasn’t of a teacher from California; it was of a blogger from Brazil — and three days after the viral tweet was posted, Twitter suspended the account.

It’s still not known whether the account was actually a person, a sockpuppet or an automated account in a “bot” network (or, as Nimmo suggests, a combination). In any case, here are things you can look for to determine whether an account may be a “bad actor,” actively spreading misinformation or sowing discord.

What is a “troll”? This describes a person who deliberately posts offensive, inflammatory, highly partisan content in order to provoke people. Trolls will often write posts and join discussions for the sole purpose of causing conflict. In an article for Psychology Today, Jesse Fox, an associate professor at Ohio State University’s School of Communication, suggests that trolls cultivate their online personalities for a variety of reasons, including the perception of relative privacy or anonymity — and hence a lack of consequences — online.

To determine whether you’re dealing with a troll, look at the history of the account. Does it regularly post content that is inflammatory, offensive or highly partisan? Are the images designed to anger or offend? Do posts on the account use disparaging language directed at specific people? These are all warning signs on accounts by trolls, and by other bad actors as well.

What is a “sockpuppet”? This type of impostor account involves the creation of a false online identity, often to influence opinion about a person or organization with the intention of making it seem like the account is not affiliated in any way with that person or organization.

If the content of the posts are overly flattering about or defensive of a person, organization or cause, you might be looking at a sockpuppet, especially if there is a lot of negative attention being directed at that person, organization or cause. (An example would be an author who creates fake accounts to leave positive reviews of his book on Amazon.)

What is a “bot”? Bots are “automated user accounts that interact with Twitter using an application programming interface (API).” Think of it as a computer program that is designed to post content automatically according to a set of guidelines, without human intervention.

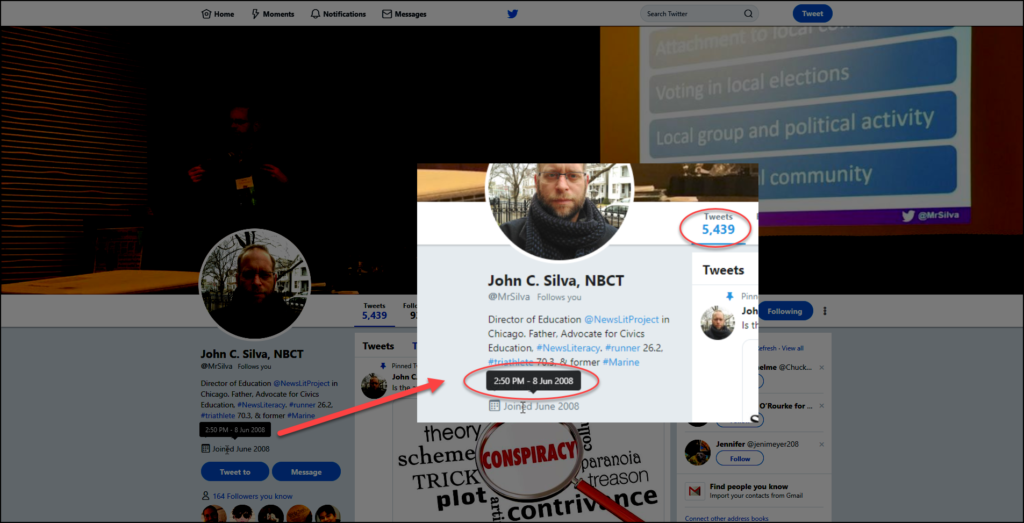

Generally, if you’re trying to determine whether an account is human-powered or automated, any account that posts more than 50 times a day should be met with skepticism. If you hover your cursor over the “joined” date on Twitter (see image below), you can see the exact time and date the account was created. Using a little math with the number of tweets posted, you can get a general sense of how many tweets a day/week/month the account posts.

Let’s look more closely at @2020fight’s Twitter account, saved through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. In a little over two years — from Dec. 3, 2016 (when it was created), to Jan. 20, 2019 (when the account holder announced “a little Twitter break”) — it averaged 84 posts and 139 likes a day. (That said, the account’s history reveals that its activity included both retweets with original comments and replies to others’ tweets, an indication that a human may actually have posted some of the content.) This contrasts with, as an example, the @USFreedomArmy account, which has posted over 450,000 tweets since December 2012 — an average of more than 200 tweets per day — but with few likes, replies or retweets.)

How do I check out an account to see if it is a bad actor? If what you’re reading causes a strong emotional reaction (especially a negative one), take some time to look deeper. The Digital Forensics Research Lab has an excellent online resource, “#BotSpot: Twelve Ways to Spot a Bot,” on Medium. And while it’s often impossible to state with complete certainty that an account is a bot, tools such as Botometer and Botcheck.me can be helpful. Also, since bad actors often have false information in the account profile, do a reverse image search on the profile photo and see if it appears elsewhere.

How do I report a bad actor account? The good news is that social media platforms are making it easier to report abusive behavior and accounts. Here are some key links.

Recognizing the differences between legitimate and misleading (or even false) political and social discourse is an essential component of being a critical consumer of news and other information — and a constructive participant in the national conversation. Engaging bad actors online only serves to derail this vital civic activity.