The Sift: Big week for Big Tech | False rally photo walkthrough | Doomscrolling woes

|

|

Teach news literacy this week |

|

Big week for Big Tech As the U.S. presidential election draws near, social media companies are taking action against falsehoods and questionable content posted on their platforms, sparking fresh controversy on the timing and scope of such efforts.

|

|

|

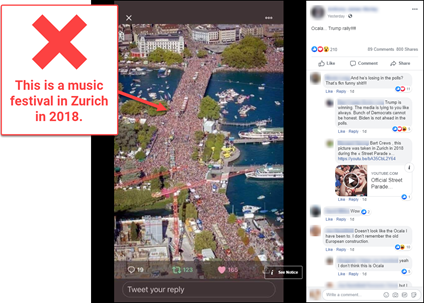

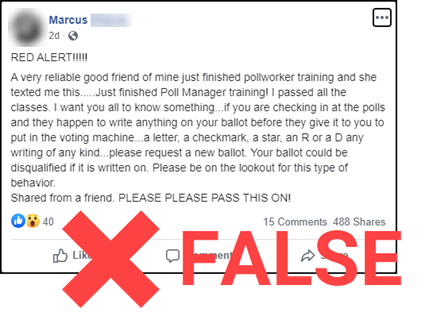

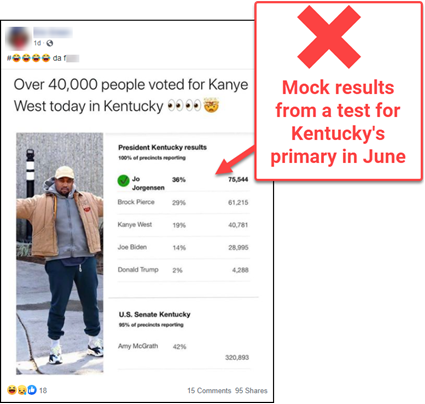

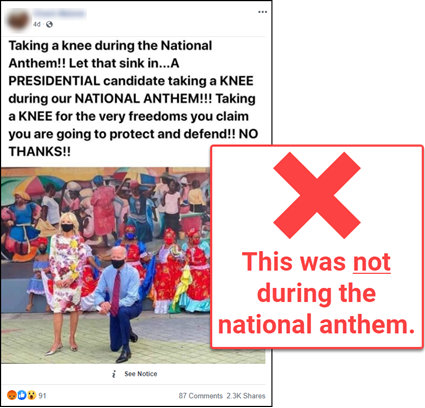

Viral rumor rundown  NO: This aerial photo does not show crowds at a rally for President Donald Trump in Ocala, Florida. YES: The photo shows a crowd of more than 1 million people at the 2018 Street Parade music festival in Zurich, Switzerland. YES: More than 5,000 people attended a rally for Trump at the Ocala International Airport on Friday, Oct. 16.  YES: President Donald Trump’s son Eric Trump did say his father “literally saved Christianity” in an Oct. 2 radio interview (advance to 23:18 in the recording). NO: He did not say “It was illegal to even say Merry Christmas and now you can say it year round, anywhere you want. I hear it everyday.” NO: This interview was not with Fox News Radio. YES: It was on What’s On Your Mind?, a conservative talk show broadcast on four local radio stations in the U.S. northern Plains and several Canadian provinces.  NO: If a poll worker were, for some reason, to write on a ballot, it does not invalidate that ballot. NO: Poll workers generally do not write on ballots except, in some states, to verify the ballot’s authenticity with a signature or stamp. YES: Several iterations of this copy-and-paste rumor recently went viral on Facebook, gaining traction with voters outside South Carolina, where the claim appears to have originated.  NO: Musician and independent presidential candidate Kanye West did not get 40,000 votes for president on Oct. 13, the first day of early voting in Kentucky. YES: A screenshot of a cached webpage from LEX 18, a local NBC affiliate in Lexington, containing randomly generated testing data from the Associated Press, went viral on Oct. 13. NO: These results do not reflect actual votes. YES: West appears on the ballot in Kentucky and a number of other states this year as a candidate for president. YES: West tweeted about the simulated results, and appeared to celebrate them in a video after the screenshot went viral.  NO: Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden did not kneel during the national anthem at a campaign event in Miami on Oct. 5. YES: Biden knelt while posing for a photo (and maintaining social distance) with a dance troupe that had performed at the event. NO: The national anthem was not playing at the time the photo was taken. |

|

News Goggles Recognizing the difference between news and opinion is a core news literacy skill. Straight news coverage primarily seeks to be as fair, accurate and impartial as possible, while opinion writing generally shares a specific point of view. This week, we want to keep these distinctions in mind as we examine the ongoing debate over The New York Times Magazine’s award-winning 1619 Project, which marks the 400th anniversary of the beginning of slavery in America. |

|

★ Sift Picks Suzannah: “The news is driving you mad. And that’s why you can’t stop devouring it.” (Elahe Izadi, The Washington Post). Discuss: How is the current news cycle affecting you? If adversely, what steps can you take to prevent getting overwhelmed or anxious? Peter: “‘It’s been really, really bad’: How Hispanic voters are being targeted by disinformation” (Tate Ryan-Mosley, MIT Technology Review). Hannah: “Opinion: Can The NPR Approach To News Survive 2020?” (Kelly McBride, NPR). |

|

|

What else did we find this week? Here's our list. |

|

Thanks for reading! Your weekly issue of The Sift is created by Peter Adams (@PeterD_Adams), Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington (@HannahCov) of the News Literacy Project. It is edited by NLP’s Mary Kane (@marykkane). |

|