The Sift: Confusion breeds conspiracy | Debate rumors | News on YouTube

|

|

Teach news literacy this week |

|

|

Confusion breeds conspiracy When President Donald Trump tweeted at 12:54 a.m. ET on Oct. 2 that he and first lady Melania Trump had been diagnosed with COVID-19, it touched off a flood of conspiracy theories online from people seeking to make sense of the news. Some on the left and others critical of the president speculated that he was faking the diagnosis to avoid participating in more presidential debates, to gain sympathy votes or to distract everyone from The New York Times’ Sept. 27 investigative report about his taxes. Others suggested his intent was to stage a quick recovery to “prove” that the disease isn’t serious or to make himself look strong and healthy. Some on the right also thought he might be faking it to lure liberals into making disgraceful comments online, while others suggested that the Democrats infected the president to gain political power.

|

|

|

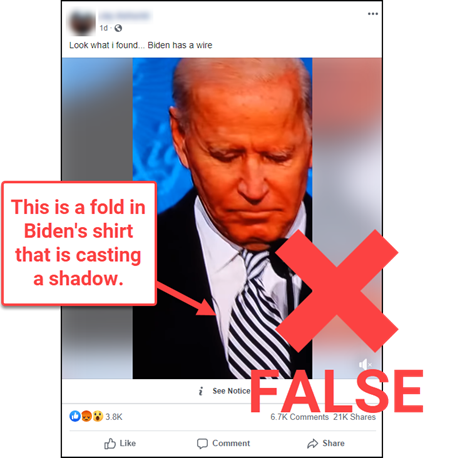

Viral rumor rundown  NO: The video in this tweet does not show bikers praying in support of President Donald Trump and first lady Melania Trump after they were diagnosed with COVID-19. YES: It is an Aug. 29 video of a protest against violent crimes targeting farmers in South Africa.  NO: The Trump campaign did not send a fundraising email asking for donations to help the president recover from COVID-19.  NO: President Donald Trump did not have an oxygen tank and tubing concealed under his jacket as he boarded Marine One to be taken to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center on Friday. YES: Trump was given oxygen at the White House on Friday before leaving for Walter Reed.  NO: Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden did not wear a wire during the first presidential debate on Sept. 29. YES: That is a fold in Biden’s shirt (you can see this moment in context here). NO: Biden does not have a transmitter implanted in his skull to receive debate guidance. NO: Biden did not have an IV or a wire running up his sleeve during the debate either. YES: He was wearing a rosary that he wears in remembrance of his son Beau, who died of brain cancer in 2015.

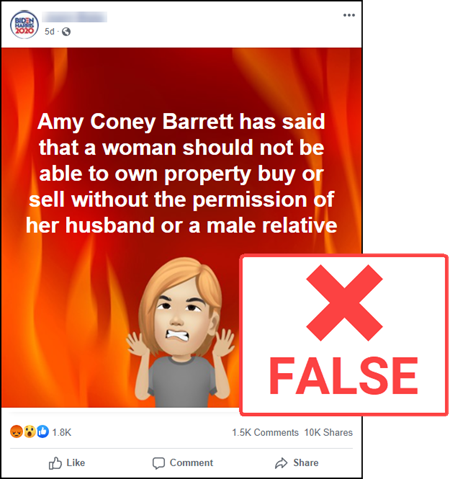

NO: President Donald Trump does not have a “neural stimulator device” attached to his head. NO: The above photo is not from the Sept. 29 presidential debate. YES: The photo has been circulating online since at least March 2016.  NO: Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett did not say that a woman should not be able to own, buy or sell property without the permission of her husband or a male relative. YES: This is a baseless assertion for which there is no evidence.

Discuss: Why do these kinds of “sheer assertions” — made anonymously and entirely without evidence — go viral online? Does the image of this Facebook post (above) contain any clues about what might have motivated the person who shared it?

|

|

News Goggles News reports sometimes convey additional information to readers in the form of editor’s notes. Such notes may briefly explain how a news report has been updated or corrected. Some describe how a particular aspect of a story was handled and why. Others are longer and typically published alongside major articles or investigations to provide further context, clarity and background on a news organization’s coverage. This week, we’re going to examine an editor’s note published online on Sept. 27 that accompanied an ongoing New York Times investigation into President Donald Trump’s taxes and finances. |

|

★ Sift Picks Suzannah: “How the everyday chaos of reporting on the Trump White House played out for the world to see Saturday” (Sarah Ellison, The Washington Post).

Peter: “Exclusive: Russian operation masqueraded as right-wing news site to target U.S. voters – sources” (Jack Stubbs, Reuters). |

|

|

What else did we find this week? Here's our list. |

|

Thanks for reading! Your weekly issue of The Sift is created by Peter Adams (@PeterD_Adams), Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington (@HannahCov) of the News Literacy Project. It is edited by NLP’s Mary Kane (@marykkane). |

|