The Sift: Facebook vs. Australia | Texas rumors | Granting fresh starts

Subscribe to the free weekly educator newsletter The Sift.

|

|

Teach news literacy this week |

|

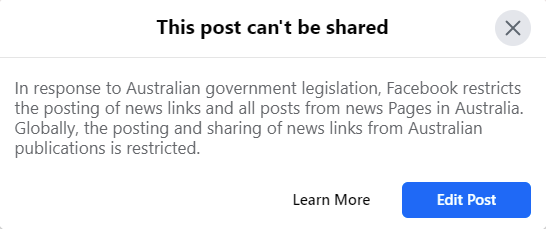

Facebook vs. Australia  A screenshot of the notification Facebook users outside of Australia receive when they attempt to post a link from an Australian news organization. Users in Australia are blocked from posting links to news from any organization in the world. Facebook and the Australian government are struggling over new regulations that would require tech companies to pay news publishers for the right to include links to their content on social media and in searches. Facebook declined to negotiate a deal with publishers (whereas Google did) and instead instituted a sweeping ban on Feb. 17 that prevents publishers and people in Australia from sharing links to news on the platform. Facebook also blocked all of its users globally from sharing links to news produced by Australian outlets. The ban — which Facebook claimed “does not provide clear guidance on the definition of news content” — also temporarily disabled the pages of a wide range of government and advocacy organizations, including a domestic violence support line, FoodBank Australia and some government-run weather, fire and health agencies.

|

|

|

Viral rumor rundown  NO: Frozen wind turbines were not the primary cause of the recent power outages in Texas. YES: Texas mostly relies on natural gas for power and heat. YES: Wind energy comprises only 10 percent of the power in the state generated during the winter, according to energy experts. YES: All sources of power in Texas — including natural gas, coal and nuclear energy in addition to renewable sources like wind and solar — were affected by a record stretch of cold temperatures, with freezing components causing shutdowns in operations and supply chains.  NO: This video shared on Twitter is not a statement from Texas Republican Sen. Ted Cruz’s director of communications. YES: It’s a satirical video posted by comedian Blaire Erskine about Cruz’s controversial trip to Cancun.

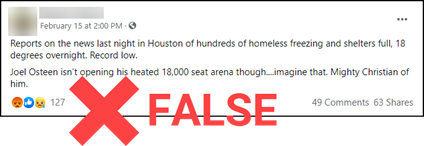

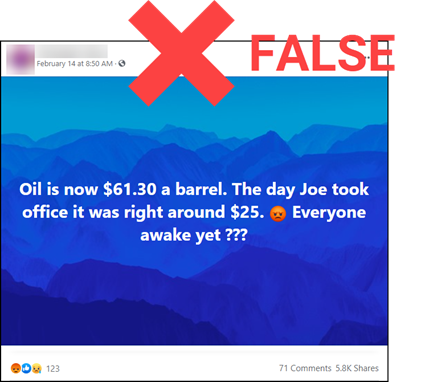

NO: Cruz did not tweet in 2016 that he’ll “believe in climate change when Texas freezes over.” YES: That’s an image of a fake tweet.  NO: Celebrity televangelist Joel Osteen did not refuse to open his “megachurch” to those affected by widespread power outages during one of the coldest winters in Texas in decades. YES: Lakewood Church, where Osteen is the senior pastor, announced that it was a designated warming center on Feb. 14. YES: In 2017, Osteen was criticized for failing to immediately open his church to those impacted by Hurricane Harvey.  NO: The second impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump did not cost $33 million. YES: This is a baseless copy-and-paste — or “copypasta” — rumor that previously circulated on social media in 2020 after Trump’s first impeachment trial. NO: That trial didn’t cost anywhere near $33 million either.  NO: The price of crude oil was not $25 a barrel on Jan. 20, 2021, when President Joe Biden took office. YES: Crude oil was more than $53 a barrel on Biden’s Inauguration Day. YES: The price of oil was $59.47 when this post was published. |

Credible sources are fundamental to quality journalism. Journalists seek out the sources they determine are in the best position to provide relevant facts and details, including eyewitnesses, officials, experts and documents. Often this information appears in the form of quotes. Quoting sources can hold officials accountable, show audiences where key facts originated and add different voices to coverage. But how do journalists decide which quotes to cite and where to put them? What kind of information is best conveyed by including direct quotes instead of paraphrasing them? |

|

★ Sift Picks Featured “Who Deserves to Have Their Past Mistakes ‘Forgotten’?” (Rachael Allen, Slate). Quick Picks “Olivia Munn, Awkwafina and More Celebrities Call for Action Amid Rise in Attacks Against Asian Americans” (Antonio Ferme, Variety).

Opinion: “Don’t Go Down the Rabbit Hole” (Charlie Warzel, The New York Times).

Opinion: “Why using Facebook and YouTube should require a media literacy test” (Mark Sullivan, Fast Company).

“Accountability suffers as newspaper closures grow in SC, nation” (Glenn Smith and Tony Bartelme, The Post and Courier).

|

|

What else did we find this week? Here's our list. |

|

Thanks for reading! Your weekly issue of The Sift is created by Peter Adams (@PeterD_Adams), Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington (@HannahCov) of the News Literacy Project. It is edited by NLP’s Mary Kane (@marykkane). |

|