The Sift: MAGA March rumors | Front-page opinion | Debunking voter fraud

|

|

Teach news literacy this week |

|

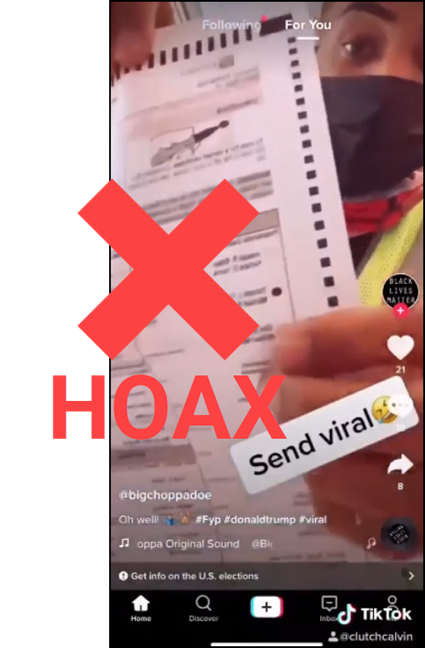

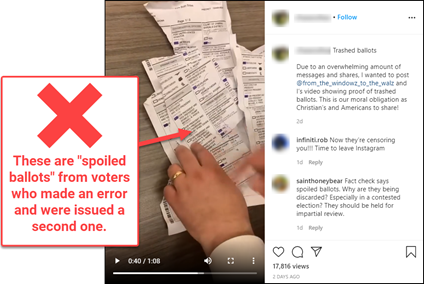

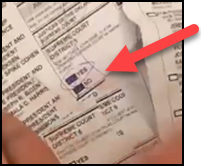

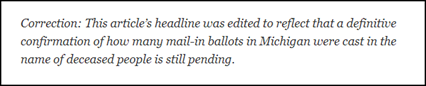

Viral rumor rundown  YES: The two photos at the top of this Facebook post are authentic aerial shots of the MAGA March in support of President Donald Trump in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 14. NO: The two photos at the bottom are not from the MAGA March. YES: They are aerial shots of the crowd at the Cleveland Cavaliers championship parade in 2016. YES: Aerial photos of crowds at a 2006 march in Dallas in support of immigration and at the 2017 Women’s March in Washington, D.C., also circulated online falsely labeled as the Nov. 14 MAGA March, often accompanied by claims that “the media” misrepresented the size of the crowd.  NO: This photo was not taken at the “Million MAGA March” in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 14. YES: It is a photo of a vendor at a flea market in Farmington, Pennsylvania, in September.  NO: This TikTok video does not show someone who is destroying ballots cast for President Donald Trump. YES: It is a prank in which no actual ballots were involved. NO: The man who created it is not an election worker. YES: He shared on Facebook that he works for Amazon and that is why he is wearing a high-visibility vest.  NO: This video is not evidence of voter fraud. YES: The ballots in this viral Instagram video were discarded at a polling place in Tulsa County, Oklahoma. NO: They are not valid ballots and were not secretly or illegally discarded. YES: They are “spoiled ballots” from voters who made an error — such as marking two options instead of one — and were reissued a clean ballot. YES: As the Oklahoma State Election Board pointed out on Twitter, one such voter error is visible in the video itself:  Both options — YES and NO — are visibly marked for the retention of a state Supreme Court justice on this ballot from the viral video. You can view a sample ballot for Tulsa County here [PDF].  NO: Over 10,000 mail-in ballots were not fraudulently cast by people in Michigan who died before Election Day. YES: Some people who cast absentee or mail-in ballots in Michigan before the election may have died before Election Day. NO: Those votes are not counted in Michigan. YES: Michigan is part of the Electronic Registration Information Center, a nonprofit organization that assists 30 states and Washington D.C., in keeping their voter rolls up to date, including death records.  Discuss: Do the revised headline and correction on the updated version of the story make the story fair and accurate? If not, how should they have been written? How does the correction exemplify the “argument from ignorance” logical fallacy? What standards of quality journalism does this example fail to live up to? |

|

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Nov. 11 promoted an editorial across the top of its front page about two Republican senators who criticized “Georgia’s election system” but “offered no specifics.” The placement choice above the news organization’s name is atypical — and attracted attention. The placement also raises questions about how prominently opinion pieces should be featured. Let’s take a closer look as we consider the differences between news and opinion as well as the role of an editorial board at a standards-based news organization. Time to grab your news goggles!

Note: An editorial board is traditionally a team that includes veteran journalists in the opinion department of a news organization. This department is separate and independent from the news department. The board is seen as the voice of the publication’s opinions, but its purpose is not to represent the views of newsroom staffers. Through articles known as editorials, this team shares opinions on major issues of public importance. |

|

★ Sift Picks Featured “The Times Called Officials in Every State: No Evidence of Voter Fraud” (Nick Corasaniti, Reid J. Epstein and Jim Rutenberg, The New York Times). Quick Picks Opinion: “The drip, drip, drip of misinformation on COVID-19 vaccine” (Claire Wardle, The Boston Globe).

“Americans Were Primed To Believe The Current Onslaught Of Disinformation” (Kaleigh Rogers, FiveThirtyEight).

“L.A. Times To Settle Pay-Disparity Lawsuit” (A Martínez, Take Two, KPCC). Segment begins at 17:22.

“How To Teach Kids Media Literacy” (Caroline Bologna, HuffPost).

|

|

|

What else did we find this week? Here's our list. |

|

Thanks for reading! Your weekly issue of The Sift is created by Peter Adams (@PeterD_Adams), Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington (@HannahCov) of the News Literacy Project. It is edited by NLP’s Mary Kane (@marykkane). |

|