The Sift: Misinformation ‘Casebook’ | Election rumors | Targeted voters

|

|

Teach news literacy this week |

|

Misinformation ‘Casebook’ Misinformation, from falsehoods to conspiracy theories, threatens our public health and the integrity of our elections. Now, a new online resource lays out specific examples of coordinated misinformation efforts and explains how they work. The Media Manipulation Casebook maps out current and previous “media manipulation and disinformation campaigns” to help educators, journalists, researchers and others understand how to detect and debunk them. The project was created by a team of researchers at Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, and led by Joan Donovan, its research director.

|

|

|

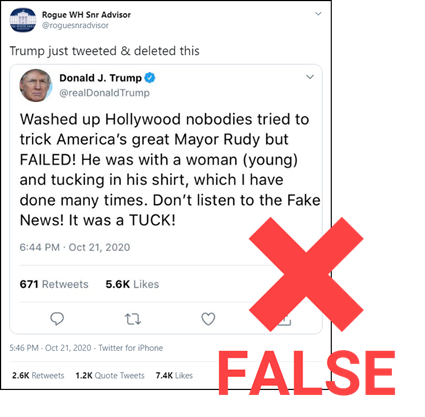

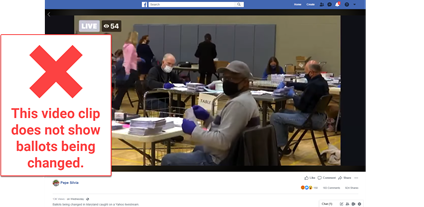

Viral rumor rundown  NO: The photo (above left) of the rappers Ice Cube and 50 Cent wearing “Trump 2020” hats is not authentic. YES: The photo (above right) of Ice Cube, wearing a hat with the Big3 basketball league logo, and 50 Cent, wearing a New York Yankees hat, is authentic. YES: Ice Cube tweeted the original photo on July 6. YES: Eric Trump, one of the president’s sons, tweeted and later deleted the doctored image on Oct. 20. YES: Ice Cube recently discussed his “Contract With Black America” with the Trump campaign. YES: 50 Cent criticized Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden’s plan to raise taxes on people making more than $400,000 a year in a recent post on Instagram (warning: foul language).  NO: This image is not an authentic tweet from President Donald Trump. YES: This is a fake tweet that circulated following the release of controversial footage involving former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani (a personal lawyer for Trump) caught up in a prank by comedian Sacha Baron Cohen.  NO: The video clip in this Facebook post does not show a Maryland poll worker changing votes on a ballot. YES: It shows an election worker darkening an oval that the voter had filled in too lightly, following the accepted protocol in Montgomery County, according to local election officials.  NO: President Trump did not say “good” in response to Democratic nominee Joe Biden’s comment that the current administration has lost track of the parents of 525 children it detained at the border. YES: Trump said to the moderator, Kristen Welker of NBC News, “go ahead.” YES: Lawyers tasked with searching for families separated at the border by the Trump administration say they are still trying to locate parents for 545 children (not 525, as Biden said). YES: Many people shared the inaccurate quote on Twitter last week.  NO: Biden did not say he’s going to tax 401(k) retirement accounts. YES: Biden has proposed changing the current tax deduction for 401(k) plan contributions to a standard refundable tax credit estimated at 26%. YES: This change means each taxpayer would receive a flat benefit for contributions, rather than one increasing in proportion to their taxable incomes. This would increase the tax benefit for people with lower incomes and reduce the benefit for people with higher incomes. |

Journalists at the Sacramento Bee, a major daily newspaper in California, say they are pushing back against a controversial proposal that could tie their pay to the page views and number of clicks that their online stories attract. News of the proposal sparked swift criticism online last week, especially among journalists, who condemned the policy as “demeaning,” “shameful” and “so appalling.” A petition to “Stop Pay-for-Clicks” at the Bee has attracted more than 1,800 signatures as of Oct. 26. |

|

★ Sift Picks Hannah: “False Political News in Spanish Pits Latino Voters Against Black Lives Matter” (Patricia Mazzei and Jennifer Medina, The New York Times).

Peter: “Facebook Promised To Label Political Ads, But Ads For Biden, The Daily Wire, And Interest Groups Are Slipping Through” (Craig Silverman and Ryan Mac, BuzzFeed News).

Discuss: How much transparency should Facebook provide about the political ads it sells? Why might Facebook not want any independent monitoring of the political ads it sells? Suzannah: “Wall Street Journal Opinion and News Side Divided on Hunter Biden” (Gene Maddaus, Variety).

|

|

|

What else did we find this week? Here's our list. |

|

Thanks for reading! Your weekly issue of The Sift is created by Peter Adams (@PeterD_Adams), Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington (@HannahCov) of the News Literacy Project. It is edited by NLP’s Mary Kane (@marykkane). |

|