The Sift: Mob reality | Antifa falsely accused | Riot or coup?

|

|

Teach news literacy this week |

|

|

|

Mob reality When the mob of extremists, conspiracists and zealous supporters of President Donald Trump violently raided the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, many of its members behaved in person how they have generally acted online. They propagated disinformation, spewed hate, stoked violence, disregarded the law and overwhelmed authorities vastly outnumbered and ill-equipped to handle the onslaught. The consequences were deadly.

|

|

Viral rumor rundown   NO: The facial recognition company XRVision did not identify supporters of the antifa movement among the mob who stormed the U.S. Capitol building on Jan. 6. YES: The openly conservative Washington Times published a report falsely claiming that XRVision had “matched two Philadelphia antifa members to two men inside the Senate.” NO: This is not true. YES: The Times removed the story from its website on Jan. 7 and replaced it with a new version with a correction. YES: Florida Republican Rep. Matt Gaetz cited the incorrect report in remarks he made on the House floor after the Capitol was secured and repeated the false claim that some of the rioters were “members of the violent terrorist group Antifa.”

NO: Capitol Police officers did not simply let this pro-Trump mob through the barricades surrounding the Capitol building on Jan. 6. YES: Marcus DiPaola, the freelance journalist who shot this video and posted it to TikTok as part of his coverage of the Capitol riots, told PolitiFact that the police “definitely didn’t just open the barriers.” YES: A number of other videos show vastly outnumbered Capitol Police fighting to protect the Capitol, including at an initial barrier on the perimeter of the Capitol grounds. YES: Some video clips also seem to show police not resisting the rioters, and at least one police officer appeared to allow a rioter to take a selfie with him.

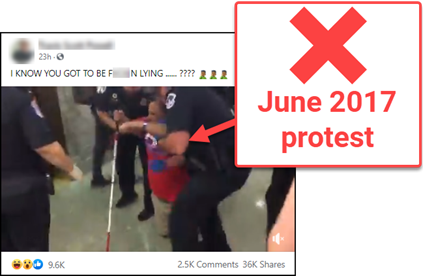

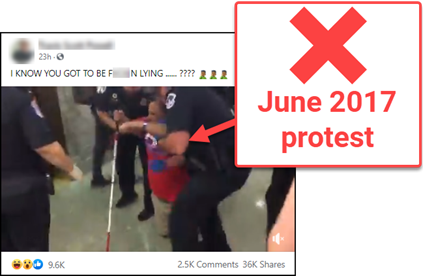

NO: This photo does not show Senate aides protecting Electoral College votes as the Senate chamber was evacuated on Jan. 6. YES: It shows aides carrying the ballot boxes from the Senate to the House chamber to be certified about an hour before rioters breached the Capitol building. YES: Parliamentary floor staff were credited with saving the ballot boxes from the mob.   NO: This video is not footage of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol building. YES: It is footage of disability rights activists protesting proposed Medicaid cuts in a Republican health care bill at the Capitol in June 2017.   NO: This photo does not show crowds of Trump supporters in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 5, 2021, the day before the Capitol riot. YES: It shows people participating in the “March for Our Lives” protest in 2018. |

|

On Jan. 3, The Washington Post broke the news about a recorded telephone conversation between President Donald Trump and Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, during which the president pressed Raffensperger to “‘find’ enough votes to overturn his defeat” to President-elect Joe Biden. Other news reports on the leaked recording soon followed, with news organizations such as CNN crediting the Post as being the first to break the story. |

|

★ Sift Picks Featured “How to describe the events at the U.S. Capitol” (John Daniszewski, AP Style Blog). Related:

Note: Journalists at the Toledo Blade say management “manipulated wording in headlines, stories, and photo captions to alter the reality of what occurred” on Jan. 6, including avoiding describing rioters as Trump supporters in headlines. The Blade’s news guild announced a temporary byline strike, removing journalists’ names from stories. Quick Picks “This Pro-Trump YouTube Network Sprang Up Just After He Lost” (Craig Silverman, BuzzFeed News).

“How to reduce the spread of fake news — by doing nothing” (Tom Buchanan, NiemanLab).

“How a Florida reporter became a one-woman help desk for anxious seniors navigating the COVID-19 vaccine” (Kristen Hare, Poynter).

|

|

|

What else did we find this week? Here's our list. |

|

Thanks for reading! Your weekly issue of The Sift is created by Peter Adams (@PeterD_Adams), Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington (@HannahCov) of the News Literacy Project. It is edited by NLP’s Mary Kane (@marykkane). |

|