The Sift: Press freedoms 2020 | Vaccine rumors spike | Understanding news sources

|

|

Teach news literacy this week |

|

|

The state of press freedoms In a year dominated by history-making news — a global pandemic, the renewed movement for racial justice, a divisive U.S. presidential election — it can be easy to overlook the risks journalists face in doing their jobs. A report (PDF) by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) serves as a reminder of these dangers, highlighting that 42 journalists have been killed in 2020 so far in crossfire, bombings and other violence in 15 countries. (IFJ reported that 49 journalists were killed in 2019.)

|

|

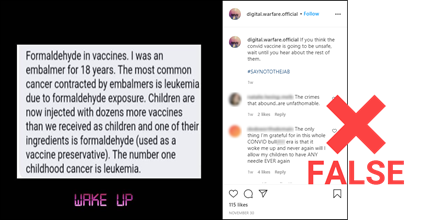

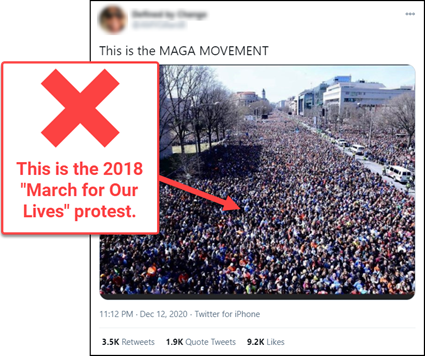

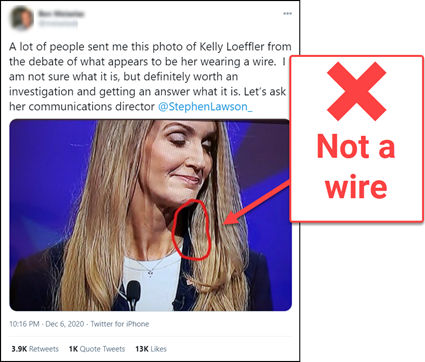

Viral rumor rundown  NO: Two people who took the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine during a trial did not die as a result of the injections. YES: The two trial participants died from other causes (one from a heart attack about two months after the second dose, and another from “baseline obesity and pre-existing arteriosclerosis,” or hardening of the arteries).  NO: There is no microchip in the COVID-19 vaccine. YES: The video in this Facebook post includes out-of-context clips of an interview — originally broadcast on the Christian Broadcasting Network talk show The 700 Club on May 22 — with Jay Walker of ApiJect Systems Corp., a medical technology company. YES: In the interview, Walker described an emergency tracking feature on the exterior of a syringe the company developed with government backing to expedite delivery of the COVID-19 vaccine. NO: The optional Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) chip on the syringes would not track patients’ personal location. YES: It is designed to track vaccine expiration and the location of delivery, and to combat counterfeiting of the vaccine. YES: The headline on the original story on The 700 Club website is also misleading. YES: This same video clip has been used to spread misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine before.  NO: There is no evidence connecting leukemia in children with the trace amounts of formaldehyde in vaccines. YES: Formaldehyde is an organic compound that occurs naturally in the human body. NO: Neither the Pfizer nor the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine contains a preservative. YES: False claims about formaldehyde in vaccines have circulated for years and resurfaced as COVID-19 vaccines were in development.  NO: This photo does not show a gathering of supporters of President Donald Trump. YES: It shows participants in the 2018 “March for Our Lives” protest against gun violence. YES: Thousands of people gathered in Washington, D.C., on Dec. 12 for the second “Million MAGA March.”  NO: Georgia Republican Sen. Kelly Loeffler did not wear a wire in a Dec. 6 debate with Rev. Raphael Warnock, her Democratic opponent in the upcoming Jan. 5 runoff elections. YES: This is a common false accusation made about political candidates. |

|

It’s a fear that can keep a journalist up at night: a factual error in a news report. Accuracy is paramount in journalism. Journalists at standards-based news organizations work to verify and fact-check each piece of information in their reporting. But what happens when occasional mistakes occur? Quality news organizations take factual inaccuracies very seriously. When journalists discover mistakes, they should correct the information as soon as they can and provide clear explanations. |

|

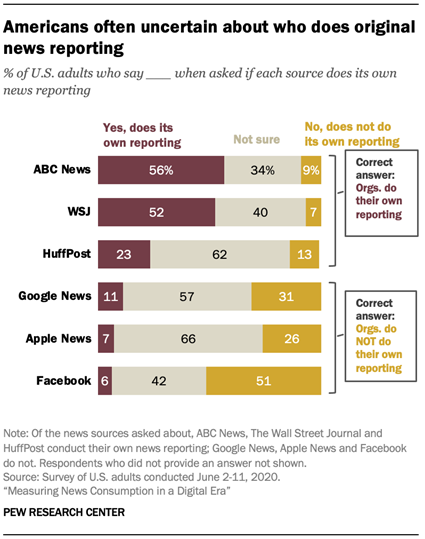

★ Sift Picks Featured  “Measuring News Consumption in a Digital Era” (Pew Research Center). Quick Picks “Online influencers have become powerful vectors in promoting false information and conspiracy theories” (Ali Abbas Ahmadi and Esther Chan, First Draft).

“'Facebook Gets Paid'” (Craig Silverman and Ryan Mac, BuzzFeed News).

“Predictions for Journalism 2021” (Nieman Lab).

|

|

|

What else did we find this week? Here's our list. |

|

Thanks for reading! Your weekly issue of The Sift is created by Peter Adams (@PeterD_Adams), Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington (@HannahCov) of the News Literacy Project. It is edited by NLP’s Mary Kane (@marykkane). |

|