GSAN: Stanford showdown over student journalist | AI romance

Dec. 10, 2024

Subscribe to this newsletter.

Your guide to helping young

people get smart about news.

| Hi there, In case you missed it, we had a new science and wellness claims quiz in our previous issue of Get Smart About News. This eight-question quiz features social media claims and asks you to evaluate them for evidence — complete with news literacy tips. Be sure to check it out if you haven’t already! Sincerely, — The Get Smart About News team |

In this issue

Stanford showdown over student journalist | AI romance

Top picks

This section highlights the latest news literacy topics and ways for you to engage with the kids in your life.

| A Stanford University student faces criminal proceedings after covering anti-war protests. |

1. University pushes for student journalist to face prosecution

A student journalist at Stanford University who covered a pro-Palestinian campus protest is facing criminal proceedings — including felony allegations of burglary, vandalism, and conspiracy.

Freshman Dilan Gohill was arrested on June 5 while reporting for The Stanford Daily, the university’s student newspaper. Gohill followed protesters into the university president’s office building and was taken into custody along with the protesters, who barricaded themselves inside. Gohill was wearing a press badge, a Stanford Daily sweatshirt and a camera to identify himself as a journalist. According to Columbia Journalism Review, Stanford officials continue to push for Gohill to face prosecution, stating he “had no First Amendment or other legal right to be barricaded inside the president’s office.”

In his first interview since his arrest, Gohill told CJR that he doesn’t regret reporting the story and believes it was important to cover the protest from inside the building.

| Engage: |

If you have college kids in your life, share this Columbia Journalism Review story and ask them what they think. Do they agree with Gohill’s decision to follow the protesters? Why or why not? What kinds of risks do journalists take to report on breaking news stories? How far should journalists go to cover a story when arrests are possible?

| Related: |

★ Tool for the talk:

Poster: “The First Amendment”

2. Watchdog journalists weed out corruption

Most Americans across the political spectrum (74%) agree that criticism from news organizations keeps politicians from doing things they shouldn’t, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. However, their attitudes about watchdog journalism tend to shift depending on which political party controls the White House. The last time this many people surveyed shared the view that news coverage keeps political leaders in check was in 2016, prior to President-elect Donald Trump’s first win, according to Pew.

Pew also found that most Americans (77%) believe news organizations tend to favor one side in social and political news coverage — nearly the highest it’s been since the research organization began surveying this issue in 1985.

| Engage: |

Discuss this topic with the kids in your life. How do journalists serve as a “watchdog” for the public? Why do perceptions of news media change during different presidencies?

| Related: |

- “Public corruption prosecutions rise where nonprofit news outlets flourish, research finds” (The Journalist’s Resource).

★ Tool for the talk:

Infographic: “In brief: News media bias” (NLP’s Resource Library).

3. Angry? You’re more likely to spread misinfo

Making people feel outraged is an effective way to spread misinformation — and foreign purveyors of disinformation use this tactic regularly, according to a Washington Post analysis of two new studies. The first study, in the journal Science, found that social media users who share content that angers them are less likely to read or verify it before sharing, and content from low-quality sources — including hyperpartisan sites — is more likely to provoke outrage.

A separate report from the nonprofit Issue One found that foreign disinformation in the 2024 election aimed to tap into similar strong emotions, such as anger, fear and mistrust. The report identified 160 false narratives spread by Russia, Iran, and China, and concluded these foreign influence operations used “pink slime” websites that misleadingly imitate genuine news sites, networks of trolls, and generative artificial intelligence technology to spread falsehoods.

| Engage: |

Talk with the young people in your life about content that makes them angry online. What steps could they take to counter misinformation? Why does outrage drive misinformation online? Why would social algorithms prioritize content that provokes strong emotions?

| Related: |

- Video: “Misinformation evokes more outrage than trustworthy news, study shows” (Good Morning America, ABC News).

★ Tool for the talk:

Infographic: “In brief: Misinformation”

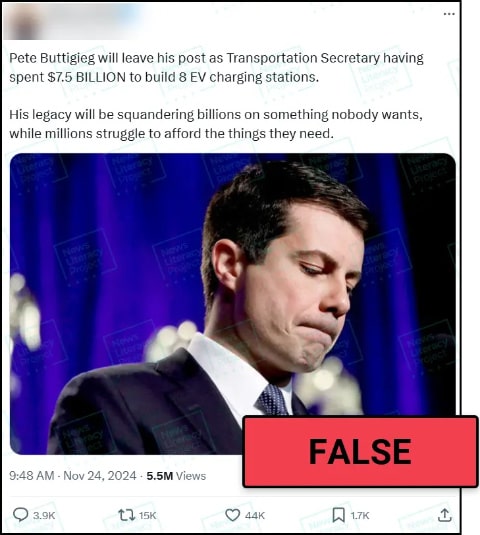

No, Pete Buttigieg didn’t spend billions for just a few electric vehicle charging stations

❌ NO: Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg did not spend $7.5 billion to build just eight EV charging stations.

✅ YES: The $7.5 billion figure is the total amount of money provided by the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to build a network of publicly available charging stations across the country.

✅ YES: States are applying for grants to fund the charging networks, and the bulk of the $7.5 billion has not yet been spent.

✅ YES: As of 2024, this program has been used to build more than 200 chargers across 12 states.

★ NewsLit takeaway

Political attacks often leave out vital context for the sake of scoring partisan points, so it is important to check explosive claims against impartial, credible sources. Here are some tips to recognize and verify these kinds of claims:

- Check for evidence. This post was not accompanied by any links or supporting evidence, a red flag that is cause for skepticism.

- Look for keywords. Use specific figures, such as “eight EV chargers” and “$7.5 billion,” to search online for additional context.

- Consider the source. To verify a social media claim, consider researching sources that can provide accurate, reliable information about the topic — and avoiding those that lack expertise and aren't credible.

| Finance bros, girl bosses, and Abercrombie & Fitch are some of the topics featured in Bloomberg Businessweek’s year-end “jealousy list,” a compilation of excellent journalism envied (and admired!) by newsroom staff. | |

| The owner of the Los Angeles Times plans to add an AI-generated “bias meter” to its news coverage that he says will give readers “both sides” of a story. The move prompted a backlash from Times journalists, who said the newsroom already abides by strict ethical standards, including “vigilance against bias.” | |

| Following the election, Americans are being targeted online by a Russian disinformation campaign pushing anti-Ukraine narratives through fake videos and a network of websites. | |

| Fact-checking can only go so far in countering misinformation, writes the founder of the investigative journalism organization Bellingcat. Increased accountability from social media platforms and more education are also needed, he argues. | |

| This Texas Observer piece reveals the identities behind four major neo-Nazi X accounts, which collectively had 500,000 followers at their peak. After Elon Musk took ownership of Twitter, he allowed formerly banned neo-Nazi accounts back on the platform, and many post anonymously to conceal their identities. | |

| The consumer protection watchdog group Public Citizen says celebrity doctor Mehmet Oz (known as “Dr. Oz”) potentially violated influencer marketing standards by failing to disclose financial connections to certain herbal supplements he promotes on social media. President-elect Donald Trump has nominated Oz to run the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. | |

| There may be a less direct way to counter misinformation: “bypassing.” New research suggests that this strategy — which offers accurate information that implies the opposite of falsehoods presented — is less confrontational but effective. | |

| Could AI bots become so realistic that people fall in love with them? It’s a premise explored in sci-fi films and this longform Verge piece, which follows the interactions a man has with Lila, an AI companion. | |

| AI images are looking more realistic as technology advances. Can you tell which image is real in this collage? | |

| Be wary of results from ChatGPT’s new search tool, which are often unreliable or inaccurate, according to recent testing by researchers at Columbia’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism. |

Thanks for reading!

Your weekly issue of Get Smart About News is created by Susan Minichiello (@susanmini.bsky.social), Dan Evon (@danieljevon), Peter Adams (@peteradams.bsky.social), Hannah Covington (@hannahcov.bsky.social) and Pamela Brunskill (@PamelaBrunskill). It is edited by Mary Kane (@mk6325.bsky.social) and Lourdes Venard (@lourdesvenard.bsky.social).

For more tips on talking with kids about news literacy, take a look back at previous Get Smart About News issues in the archives.