Levels of scientific evidence

Claims that cite scientific evidence are seemingly everywhere — in our social media feeds and in headlines from standards-based news organizations. But all “evidence” isn’t created equal. An anecdote posted by a stranger online might feel compelling — especially if it resonates with our own experiences in some way — but is it really evidence? News headlines commonly tout the findings of “a new study,” but how authoritative are those findings?

To help answer these questions, we worked with Dr. Katrine Wallace — an epidemiologist, educator and science literacy influencer — to produce a trio of resources focused on differentiating between different levels of scientific evidence.

View the PDF here.

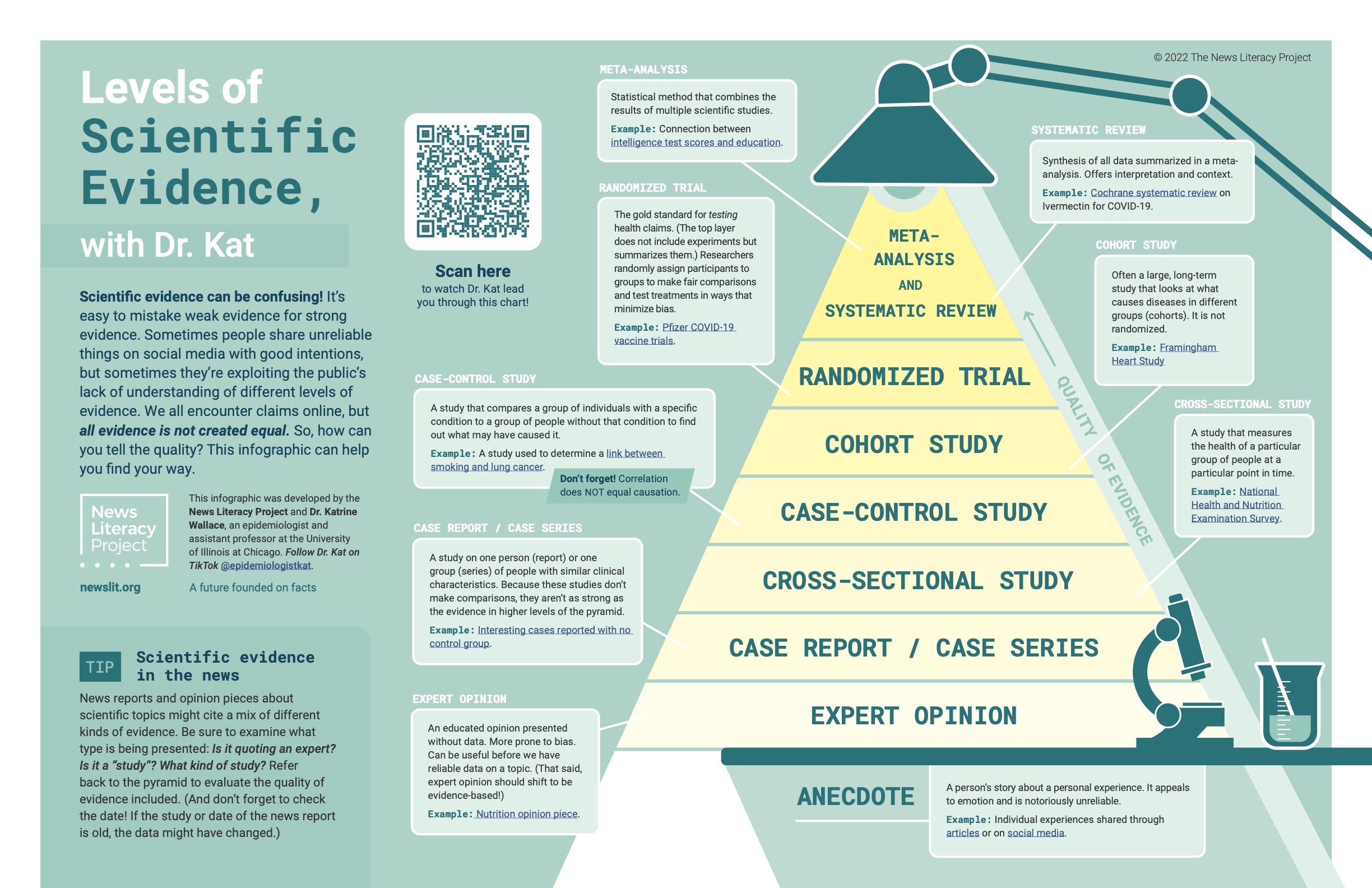

This infographic presents eight distinct levels of scientific evidence arranged in a pyramid that reflects a spectrum of quality. Levels of evidence at the bottom are significantly more prone to error and bias than those at the top. The pyramid is reflective of the process of science itself: as initial hypotheses about a given question are tested, they are either disproven and discarded or they survive to be tested further. As more rigorous studies are completed, and as their results are compiled and analyzed, the picture painted by the evidence becomes clearer and more compelling.

The eight levels of scientific evidence on the infographic are here, in order from weakest to strongest:

- Anecdotes: Stories about personal experiences and perceptions are notoriously unreliable and should not be considered scientific evidence.

- Expert opinions: Experts often base opinions on evidence, but they also sometimes offer informed perspectives on issues about which the data isn’t yet clear. Remember: experts aren’t immune to bias.

- Case reports / case series: These are studies on one person (case report) or a group of people (series) with similar clinical characteristics. These are common with new diseases or health conditions and are used as a first step to gather more information.

- Cross-sectional studies: Observational studies in this category capture the health of a particular group of people at a single point in time. These provide useful snapshots, but they can’t show what caused a disease or ailment.

- Case-control study: These observational studies compare groups of people with a specific condition with other groups of people who do not have that condition. It’s important to remember, however, that some correlations in these groups could be the result of coincidence.

- Cohort study: These large, long-term observational studies look at what causes diseases in different groups (cohorts) by following a group that shares a specific factor or exposure to a risk factor over time to see if they develop a mutual ailment.

- Randomized trial: This is the gold standard for testing health claims. Participants are randomly divided into control groups (no treatment) and test groups (receive a given treatment) to minimize the influence of bias.

- Meta-analysis and systematic review: These are not studies themselves, but rather analyses and reviews of a group of studies, filtered for quality and rigor. In other words, these reviews collect studies about a subject or question, then narrow that group down to the strongest studies and analyze or review their collective findings.

The next time you encounter a claim about what the scientific evidence shows, refer back to Dr. Kat’s levels of evidence as a guide to help you evaluate it.