NLP founder named an Ideagen Global 2023 Power Innovator

Ideagen® Global has named NLP founder Alan C. Miller a 2023 Power Innovator. In notifying Miller of the award, Daniel F. Kerns, chief of staff and vice president of operations at the company, said: “The 2023 Power Innovators recognition focuses on an individual’s leadership in innovation, characteristics, and impact. Thank you for your contributions to your respective field, which have earned you this recognition.”

Ideagen said it is honoring Miller as a Power Innovator for his commitment to news literacy and dedication to eradicating misinformation. “A former journalist with the L.A. Times, Alan is a 2022 AARP Purpose Prize winner for his work at the News Literacy Project. Alan works with schools and individuals to give the tools to spot misinformation and evaluate the news critically. Through tools like RumorGuardTM, the News Literacy Project wants to ensure every American can spot disinformation and stop it from spreading.”

The mission of Ideagen is to create a platform for collaboration among leading corporations, non-governmental organizations and the public sector to drive innovation and find solutions for some of society’s most challenging problems.

A pioneer in the field of news literacy

Miller founded NLP in 2008 to give middle and high school educators the tools to teach their students how to separate fact from fiction in the digital age. A founder of the field of news literacy, Miller has helped raise nearly $50 million for NLP and oversaw its growth to a team of more than 40 staff members. It is now the leading provider of news literacy education in the country, and the organization is marking its 15th anniversary this year.

Miller lead NLP for 14 years, stepping down as CEO in June 2022. Watch this video to learn more.

NLP ‘is a model’: Journalist Margaret Sullivan’s new book

In her new book, Newsroom Confidential: Lessons (and Worries) from an Ink-Stained Life, Margaret Sullivan writes about her career in journalism and notes the pioneering work of the News Literacy Project under the leadership of founder Alan C. Miller.

In her new book, Newsroom Confidential: Lessons (and Worries) from an Ink-Stained Life, Margaret Sullivan writes about her career in journalism and notes the pioneering work of the News Literacy Project under the leadership of founder Alan C. Miller.

She describes the impression that Miller made on students in her media ethics class at Duke University when he spoke to them in 2021 and argues that there is a vital need for news literacy programs and resources like those NLP creates for people of all ages.

She writes: “It’s important, too, for news consumers, also known as American citizens, to take responsibility for their own news literacy. I’m not terribly hopeful about this happening on its own, given the trends. I’m worried, too, about what it would mean to legislate it. Trying to get news literacy taught in public schools, given the turmoil over curriculum in recent years, could have unexpected negative consequences. I still think it’s worth pursuing. I might even put Alan Miller in charge of it if I had the power.

“…We need a widespread effort to educate the public — not just schoolchildren but adults, too, about news literacy and about the deadly harm of not knowing the difference between truth and lies. The News Literacy Project, which has expanded to include adults, is a model.”

A widely respected journalist, Sullivan was the media columnist for The Washington Post, leaving the paper in August. Before that, she served as the first woman to hold the position of public editor of The New York Times, acting on behalf of readers regarding the paper’s reporting and writing or lapses in coverage, and she was the first woman to serve as editor of the Buffalo News.

East-West Center honors NLP founder with Distinguished Alumni Award

The East-West Center, an independent, public nonprofit that works to improve relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia and the Pacific, awarded NLP founder and former CEO Alan C. Miller with its 2022 EWC Distinguished Alumni Award June 30 in Honolulu.

The honor recognizes outstanding accomplishments, including major contributions to the EWC mission, significant career achievements and continuing support for the goals and objectives of the Center. The awards were presented at the East-West Center/East-West Center Association conference. Miller was unable to travel to Hawaii to accept the award but delivered remarks to conference attendees via video. The text of those remarks is below.

‘Demonstrated excellence and achievements’

Miller had a distinguished career as a Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist with the Los Angeles Times before founding NLP in 2008. He earned a master’s degree in political science in 1978 from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and was a student participant at the Center’s Communications Institute from 1976 to 1978. He also completed an internship in The Washington Post’s Tokyo bureau and edited the student magazine, Impulse.

The Center is recognizing Miller for “the demonstrated excellence and achievements in his initial and second careers, which are both worthy of recognition. Building on the skills and cross-cultural experience he gained at the Center, he has demonstrated integrity, determination, vision, creativity, courage and professional commitment to journalism and education and remained supportive of the goals of the Center. Miller continues to support the goals and objectives of the Center by participating in Center events and remains in touch with Center friends and colleagues.”

He was honored alongside Andolgor Purevjav, a leader, author, human resources consultant and mentor in Mongolia who incorporates the Center’s values through her work with the Ganabell Institute of Success.

Miller’s remarks

I’m sorry that I can’t be with you all in person but I’m there in spirit.

Thank you so much President Vares-Lum, Jim Scott and the alumni association for this very special and meaningful honor.

A heartfelt mahalo goes to my former East-West Center colleague and friend Tinu Brara, who is with you, for having nominated me.

My time at the center was one of the most consequential and enriching experiences of my life.

I had previously spent a college semester in Japan. But it was my time in Honolulu — and through such experiences as attending programs at Jefferson Hall, enjoying the camaraderie and international cuisines at food co-ops in Hale Manoa, co-editing the student magazine Impulse and gaining a master’s degree at UH — that opened up the rest of Asia and the Pacific for me. It was there that I formed deep friendships that have lasted nearly half a century.

As an aspiring journalist, I enjoyed helping host Jefferson Fellows from Japan, Singapore and Thailand and am delighted to see that this program is still thriving.

My field study was a highlight of my experience. I was fortunate to land an internship in The Washington Post’s Tokyo bureau, three years after the paper broke the Watergate scandal. I got to shadow the Post’s East Asia bureau chief, complete a project on the American press in Japan and write two stories published by the paper.

My internship with the Post led to my first fulltime newspaper job working for Harry Rosenfeld, who had been Woodward and Bernstein’s boss at the paper during Watergate. Harry had just left the Post to edit two papers in Albany, N.Y., and I was his first hire. He was an exacting and inspiring boss and became a longtime friend and mentor.

When I left the center, I hoped to become a foreign correspondent based in Tokyo and was offered that chance by the LA Times. But by then I had found my calling as an investigative reporter in the paper’s Washington bureau.

Yet, I had one more special Asia sojourn in store.

In 1998, I was awarded a Japan Society fellowship and pursued two projects that reflected both the transcendent and the tawdry sides of Japan. For one, I interviewed six ningen kokuho – living national treasures – masters of traditional crafts and arts, including the country’s foremost bunraku puppeteer and a sword-maker who restored swords of the samurai.

For the other, I dug into Japan’s shadowy campaign finance practices, comparing them to what I had unearthed in my investigative work on this subject in the U.S. and turned this into a page one story for the LA Times.

Since embarking on my second career with the News Literacy Project, it has been gratifying to make connections with my center experience as well. Educators in 25 counties in Asia and the Pacific have registered to use our Checkology virtual classroom and the Yomiuri Shimbun has made some of our other resources available in Japan. Leading Asian news outlets have done pieces on us.

Moreover, educators in Hawaii have used Checkology since 2017 to reach more than 1,400 students, and we have forged a strong and growing partnership with the Hawaii Department of Education. Recently, President Vares-Lum has become an effective champion for NLP and news literacy across the state as well.

In the end, it is the close friendships forged at the center that have meant the most. This includes Stu Glauberman, my roommate in Hale Manoa and co-editor of Impulse who remained in Hawaii, and Ian Gill, a colleague at the Communications Institute who settled in the Philippines, as well as Tinu.

For all of us, Mike Anderson was an extraordinary friend at the center and for more than four decades thereafter, who we lost much too soon a year ago this month. Throughout his long, distinguished career as a diplomat in Asia, Mike epitomized the values of the center in promoting understanding, mutual respect and cooperation. He won this award in 2002. I am honored to follow in his footsteps, and in those of others who have come before me.

Thank you again for this treasured recognition and for the chance to reflect on how much the center and my experience in Hawaii have meant to me.

About the East-West Center

Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for information and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options.

Miller transitioning to new role; Salter to succeed him as CEO

Since its founding in 2008, the News Literacy Project has embraced change and adaptability to become the leading provider of news literacy education in the nation. Now, with our mission more urgent than ever, we embark on a new era with a major shift in our organization. On June 30, NLP founder and CEO Alan C. Miller will step down as CEO and transition to a new role within NLP, while our President and COO Charles (Chuck) Salter will succeed Alan as CEO on July 1. Salter also will retain the title of president, ensuring a seamless transition and continuity for the organization.

NLP’s place as a game-changer in news literacy education is the result of Alan’s vision, passion and commitment. As a founder of the field of news literacy, he helped raise more than $35 million for NLP and oversaw its growth to a team of 30 staffers. (Hear Alan tell the story of NLP’s founding in this video.)

Since 2016, more than 345,000 students have used NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom, and the organization has engaged over 50,000 educators in all 50 states and more than 120 other countries. All told, educators using NLP resources and programs in the last year reached an estimated 2 million students.

Chuck joined NLP in 2018 as its first chief operating officer and was named president in 2019. Prior to joining NLP, he spent nearly two decades in education — often working to advance opportunity in under-resourced communities — as a teacher, school leader, teachers union president and senior executive with several national education organizations. Read this Q and A with Chuck to learn more about the experience and expertise he brings to NLP.

NLP is poised to take on a more significant national presence as more school districts begin requiring news literacy education and as it continues to expand its work to reach adults. This strategic direction will enable NLP and its staff to focus on teaching people of all ages the news literacy skills they need to fully engage in the civic life of our country in meaningful and informed ways.

Cover story features NLP’s founder, highlights his impact and future of the organization

The January 2022 cover story of The Beacon features the News Literacy Project’s very own founder and CEO, Alan C. Miller. The story highlight’s Miller’s recent acceptance of the 2022 AARP Purpose Prize, which celebrates people 50 and older who use their life experience to solve social problems. Miller received the prize in recognition of his work with NLP, which he founded in 2008.

“What I’ve done with the News Literacy Project is a second kind of calling,” Miller explained.

When asked about NLP’s future, Miller stated, “We feel a great sense of responsibility to move as quickly as we can to expand our reach and impact… There’s just so much more disinformation out there,” he said, especially during the pandemic. “The threat is so much more urgent now — to not only our public life, but to our public health.”

To read the full piece, click here.

NLP founder and CEO Alan Miller receives AARP Purpose Prize

Alan C. Miller, News Literacy Project founder and CEO, is a winner of AARP’s prestigious Purpose Prize®, a national award that celebrates people 50 and older who are using their life experience and wisdom to tackle societal challenges and inspire others.

“AARP is honored to celebrate these extraordinary older adults, who have dedicated their lives to serving others in creative and innovative ways,” AARP CEO Jo Ann Jenkins said. “During these trying times in our country and globally, we are inspired to see people use their life experiences to build a better future for us all.”

AARP awards $50,000 to each honoree’s organization and provides technical assistance supports and resources to help broaden the impact of its work.

In a profile on AARP’s website Miller describes what motivated him to create NLP, the problem he hopes to solve and what makes NLP’s approach stand out. “I founded the News Literacy Project in 2008, with the belief that knowing how to identify credible news is an essential life skill in an information age — and that this was not being widely taught in schools,” Miller said.

Watch the short video that AARP produced to learn more about Miller and NLP’s impact. Recipients of the Purpose Prize also are eligible for the AARP Inspire Award. The public votes to choose the winner, whose organization receives $10,000. In this video, Miller answers AARP’s three “inspire” questions.

“We realized last year that misinformation is such an existential threat to democracy that we could not limit ourselves to reaching just the next generation. We are racing against a toxic tide of misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy theories that is undermining our trust in institutions,” Miller said. “We must find a way to bridge this divide by creating a shared narrative around verified, agreed-upon facts.

A sense of purpose

“One of the things that distinguishes NLP is our focus on news literacy, which is a subset of media literacy,” he explained. NLP uses the standards of quality journalism as an aspirational yardstick against which to measure all news and information, partners with journalists who share their skills, provides an understanding of how quality journalism works and instills an appreciation of the First Amendment and the role of a free press in our society.

“We don’t teach people what to think; we teach people how to think. We help them develop critical thinking skills to make judgments about whatever they encounter in the information landscape.”

He also shared his advice for others who want to make a difference in the world. “Start with something for which you have a passion and a sense of purpose. For me, journalism was always a calling, not just a career. In NLP, I feel blessed to have found a second professional calling.”

Read about this year’s other Purpose Prize winners, as well as Honorary Award recipient actor Michael J. Fox, selected for his advocacy work to help advance scientific progress toward a cure for Parkinson’s disease.

Alan Miller: How to Know What to Believe

Alan Miller, NLP’s CEO and founder, was interviewed by the Aspen Institute for its Disinfo Discussions digital series. In the conversation, Alan examined the role of news literacy and education as an effective countermeasure to the spread of mis- and disinformation. “We don’t tell people what to think. We are giving them the tools to develop how to think… All sources, even the most credible sources, combine news and opinion, advertising. They’re all, in some way, potentially flawed. Bias creeps in and mistakes are made – it’s inadvertent. So, we really want to give people the ability to make those judgments for themselves and to decide, ‘Should I trust this? Should I share this? Should I act on it?’.”

Listen to the full interview here.

Alan also was a guest on the Ralph Nader Radio Hour podcast, where he spoke to the former public interest lawyer and presidential candidate about the benefits of being news-literate. In response to Nader’s question about how young people classify themselves based on their political beliefs, Miller said, “When people tend to see their news and information through prisms of red and blue, they see the world in terms that are more black and white. And they close themselves off from ideas that contradict their beliefs and let their emotions overwhelm reason and evidence…I think it’s critically important that we encourage them to both have the skills to determine what’s credible, to be mindful about what they’re consuming, but also to get a wider array of sources and to challenge their beliefs.”

Listen to the full interview here.

Upon Reflection: Recalling a Great Newspaper Editor and What He Represented

This column is a periodic series of personal reflections on journalism, news literacy, education and related topics by NLP’s founder and CEO, Alan C. Miller. Columns are posted at 10 a.m. ET every other Thursday.

John Carroll was the kind of editor who made you proud to be a journalist. He inspired those who worked for him. In my case, I felt honored to call him my editor, my chairman, my friend.

John led with vision, integrity and courage. He loved a good story, especially when it held the powerful accountable. His courtly manner belied a steely resolve and an uncompromising commitment to the highest standards of journalism. I thought of him as the iron fist in the velvet glove.

This month will mark six years since John’s death at 73 from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a rare and unforgiving degenerative brain disorder. It was a devastating loss for those of us who knew and revered him. It was also an indelible loss for journalism, and for the country.

Norm Pearlstine, a prominent editor in his own right who had remained close to John since their days as Haverford College classmates, said at his friend’s memorial, “John Carroll was our generation’s greatest, most respected and most beloved editor.”

In many respects, John’s story reflects the trajectory of American journalism in the 21st century. He pushed back against the growing challenges that threatened the health of newspapers, the partisan attacks on journalism, and the rise of misinformation. Sadly, these forces have only accelerated since his passing.

I first met John when he was named the editor of the Los Angeles Times in 2000 and I was an investigative reporter in the paper’s Washington bureau. He had been editor of The Baltimore Sun (1991-2000) and, prior to that, the Lexington (Kentucky) Herald-Leader (1979-1991), shepherding both papers to Pulitzer Prizes.

John took over a demoralized staff reeling from the disclosure that the Times had published a special issue of its Sunday magazine devoted entirely to the Staples Center, a new downtown sports arena, and split advertising revenue from that issue with the arena — a fundamental breach of journalism ethics. He recommitted the paper to its high standards, recruited talented reporters and editors from across the country and reaffirmed the power and honor of journalism at its best.

When he detected a left-leaning slant to some of the paper’s coverage, he made it clear that this was unacceptable. When he learned that a veteran staff photographer covering the Iraq war had digitally manipulated an image, he promptly fired him and explained to readers why such an ethical breach was so egregious. He called factual errors “the pollution of our business” and insisted that they be promptly corrected.

Under John’s leadership, the paper revealed that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had approved seven drugs that subsequently were suspected of contributing to more than 1,000 deaths; it detailed the high price in blood and treasure of the Marine Corps’ deeply troubled aviation program; it revealed deadly medical problems and racial injustice at the Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center, a public hospital in Los Angeles; and it published “Enrique’s Journey,” an exhaustive and moving account of a Honduran boy’s harrowing journey to reunite with his mother, who had migrated to the United States 11 years earlier. These projects each won Pulitzer Prizes — five of the 13 that the paper captured during John’s extraordinary five-year tenure (“Enrique’s Journey” won for both feature writing and feature photography). I embraced the opportunity to work closely with John on the Marine Corps aviation series as well as on other projects.

In his eulogy, Dean Baquet, hired by John as the Times’ managing editor (and now the executive editor of The New York Times), called John’s success in Los Angeles “one of the finest acts of leadership — in a newsroom or anywhere else — in modern times.” He quoted a colleague as saying that watching John run the paper “was like watching Willie Mays play baseball.”

But it wasn’t enough. The business model for newspapers was collapsing. The internet had led to steep declines in both advertising and circulation as readers gravitated to free online competitors. Family-run papers and companies, finding it harder and harder to stay afloat, were being consolidated by new owners focused on shrinking the bottom line.

The Tribune Company, which had purchased the Los Angeles Times in 2000 in the aftermath of the Staples Center debacle and then hired John to run it, began demanding ever-deeper budget cuts to maintain profit margins — a demand, John said, that would kill the newsroom. Amid the widening rift between John and Tribune executives in Chicago, he stepped down in 2005.

A year later, in accepting the American Society of Newspaper Editors Leadership Award, John asked what would become of newspapers: “What will become of the kind of public service journalism that newspapers produce? … What will the public know — and what will the public not know — if our poorly understood, and often unappreciated, craft perishes in the Darwinian jungle?”

Those questions have only become more urgent. Since then, more than 2,000 newspapers in the United States have shut down, and many others have cut their staffs.

The three papers that John edited have been vastly diminished. The Herald-Leader and the rest of the once-proud, family-run McClatchy chain were purchased by Chatham Asset Management, a hedge fund, in a bankruptcy sale last year. The Baltimore Sun and other papers in the Tribune chain were acquired last month by Alden Global Capital, another hedge fund notorious for slashing newspaper staffs and selling their assets.

The Los Angeles Times suffered through a string of corporate overlords who ranged from inept to malevolent, as well as a stint when Tribune was in bankruptcy. In 2018, the paper was purchased by Patrick Soon-Shiong, a Los Angeles biotech billionaire. Pearlstine, John’s longtime friend, was the new owner’s first executive editor and presided over an initial period marked by hiring and hope. But he stepped down last year amid internal strife and reports of ethical lapses by multiple staffers, as well as financial losses and disappointing growth in digital subscriptions.

For his part, after leaving newspapers, John embarked on a new fight to retain an appreciation for the journalistic values to which he had devoted his illustrious career.

In 2008, he accepted my invitation to become one of the initial board members of the News Literacy Project, the education nonprofit that I left the Los Angeles Times to create. Our purpose was (and still is) to use journalism standards — and journalists — to help teach students how to know what they can trust, share and act on and what they should dismiss and debunk, and to give them an understanding of what sets quality journalism apart.

John served seven years on our board, including four as chairman — helping to get NLP off to a strong start and move to national scale. His reputation, devotion to the cause and managerial acumen were invaluable. It was his final principled service to the preservation of a healthy democracy.

“It is important for us to understand, in clear English, what, exactly, a journalist is, and what a journalist is not,” John said in his 2006 ASNE speech. “It is important for us to live by those beliefs, too, and to condemn those who use the trappings of journalism to engage in marketing or propaganda. And, finally, it is important for us to explain to the public why journalism — real journalism, practiced in good faith — is absolutely essential to a self-governing nation.”

John Carroll embodied journalism’s highest values. Emulating him would be both a fitting legacy and a fine way to preserve them.

Read more from this series:

- Apr. 8: The 19th* — a nonprofit news startup made for the moment

- Mar. 25: How I became a ‘pinhead’ — a news literacy lesson

- Mar. 11: Fighting the good fight to ensure that facts cannot be ignored

- Feb. 26: Students’ enduring rights to freedoms of speech and the press

- Feb. 11: We need news literacy education to bolster democracy

- Jan 28: 13 lessons from our first 13 years

- Jan. 14: Media needs to get COVID-19 vaccine story right

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Dec. 3: Combating America’s alternative realities before it’s too late

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 29: High stakes for calling the election

- Oct. 15: In praise of investigative reporting

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news

Upon Reflection: Students’ enduring rights to freedoms of speech and the press

Mary Beth Tinker addresses an audience of students at The E.W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University in 2014.

Photo by Eli Hiller / Flickr.com / CC BY-SA 2.0

Mary Beth Tinker was only 16 years old when, in 1969, her name became synonymous with freedom of speech for students.

I also was a teenager when I had my initial encounters with freedom of the press and freedom of speech. They were nowhere near as consequential for the country, but they certainly left a lasting impression on me.

Decades later, students still have to fight these battles. And since tomorrow is Student Press Freedom Day, it’s an appropriate time to reflect on these experiences, both Tinker’s and mine.

Read more from this series:

- Apr. 22: Spotlight — a special resonance

- Apr. 8: The 19th* — a nonprofit news startup made for the moment

- Mar. 25: How I became a ‘pinhead’ — a news literacy lesson

- Mar. 11: Fighting the good fight to ensure that facts cannot be ignored

- Feb. 11: We need news literacy education to bolster democracy

- Jan 28: 13 lessons from our first 13 years

- Jan. 14: Media needs to get COVID-19 vaccine story right

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Dec. 3: Combating America’s alternative realities before it’s too late

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 29: High stakes for calling the election

- Oct. 15: In praise of investigative reporting

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news

Miller talks news literacy, media credibility on ‘The Trusted Web Podcast’

NLP founder and CEO Alan C. Miller discussed news literacy and its role in democracy on The Trusted Web Podcast, hosted by Sebastiaan van der Lans. When introducing Miller in the Feb. 10 segment, Creating News Literacy with Alan Miller, CEO of the News Literacy Project, van der Lans said, “Alan and I share a passion for a more truthful internet, and we both chose the route of building a whole category as an important way of achieving it, in Alan’s case: news literacy.”

Alan’s advice to listeners includes key first steps for becoming more news-literate, including being mindful of emotions and pausing before trusting, sharing or acting on information. “The first thing is to check your emotions, because when we see something that really inflames our emotions, whether it makes us angry or anxious or even joyful, we tend to let down our guard in terms of our skepticism about what we are seeing.”

Trust in the media

He also addresses the need for news media to work to build the public’s trust through accountability and transparency. “We live in such a hyper-connected time that things move so rapidly and move out on social media, it’s just so difficult to put the horse back in the barn when mistakes are made and then they spread and get amplified so readily,” says Miller.

Miller also stresses the need for the American education system to require the teaching of critical thinking and related news literacy skills, as part of civics education or another discipline. “If we don’t teach this to the next generation, we are denying them the ability to be full and effective participants in the civic lives of their communities and their countries. It’s not only a survival skill that advantages those that are able to discern credible information today, but it’s an essential skill for them to participate in civic life,” he tells van der Lans.

Listen to the full conversation here.

Upon Reflection: We need news literacy education to bolster democracy

This column is a periodic series of personal reflections on journalism, news literacy, education and related topics by NLP’s founder and CEO, Alan C. Miller. Columns are posted at 10 a.m. ET every other Thursday.

We live in what is often called the Information Age. We have a world of knowledge available to us, literally at our fingertips. This should be a Golden Age of Knowing.

Yet, as this week’s impeachment trial reflects, America now faces an epistemological crisis. And the stakes could not be higher.

Millions of Americans believe that November’s presidential election results did not represent the will of the people. Millions also believe that vaccines are unsafe amid a global pandemic, and that a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles (who include prominent Democratic politicians) is secretly running the country.

How did we get here? And, more important, what can be done to reinforce reality-based thinking before conspiratorial thinking opens the door to tyranny?

A decline in trust of institutions, including the media; hyperpartisanship and tribalism; and the spread of divisiveness and extremism on social media platforms have all contributed to this existential challenge. At the same time, the country’s fractured civic society reflects an educational failure — one that has been some time in the making.

“As the information system has become increasingly complex, competing demands and fiscal constraints on the education system have reduced the emphasis on civic education, media literacy and critical thinking,” the RAND Corporation’s Jennifer Kavanagh and Michael D. Rich noted in their 2018 report Truth Decay: An Initial Exploration of the Diminishing Role of Facts and Analysis in American Public Life.

I founded the News Literacy Project 13 years ago to help teach the next generation to recognize the difference between fact and fiction and to understand the role of the First Amendment and a free press in a democracy. I chose to focus on reaching teens as they form the reading, viewing and listening habits that will last a lifetime.

In the last dozen years, I have seen — and, more important, educators have seen — that teaching news literacy empowers young people to question what they are reading, watching and hearing; seek credible information; be more mindful about what they share; elevate reason over emotion, and gain a greater sense of civic engagement. This is evident in anecdotal experience as well as evaluation surveys.

In assessment results of students (primarily middle school and high school) who completed one or more lessons in our Checkology® virtual classroom during the 2019-20 school year, we saw substantial gains in the percentages who could:

- Identify the standards or rules for news organizations and journalists to follow when reporting the news.

- Express greater confidence that they could recognize pieces of online content as false.

- Understand the watchdog role of a free press.

- Appreciate the role and importance of the First Amendment in our democracy.

Students have told us for years what it means for them to learn how to navigate their way through what has become a daily deluge of news, opinion, entertainment, advertising, opinion, propaganda, raw information and even flat-out lies.

“I was just overwhelmed by how much information there was,” said Kristen Locker, who received her news literacy instruction at Florida Gulf Coast University in Fort Myers. “Checkology taught me for the first time how to sort through all this information. That kind of blew open the doors for me.”

Sophia Fiallo, a student at the Young Women’s Leadership School of Astoria in New York City, said that before her news literacy training, she was “vulnerable to the spread of fake news” — but “thanks to Checkology, I’ve learned how to tell fact from fiction.”

Teachers also say that this skill is transformative for their students and their classrooms.

Nicole Finnesand, a middle school teacher in Colton, South Dakota, said that Checkology enabled her students, for the first time, to have civil discussions — ones that are not based on polarized opinions or on “arguments” published in The Onion, a satire site. “We get to use our class as a space to discuss ‘Well, what are the two sides? And how do we know what’s real and what’s not real?’”

Tracey Burger, a high school English teacher in Miami, said her students went from telling her that the Earth is flat to asking each other for verification of the information they share. Moreover, she added, they now “understand that theirs isn’t the only way to think.”

Suzanne, an English teacher in Connecticut whose students used Checkology prior to the Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol, said that because of what they learned, “we were able for the first time in five years of teaching to have a good conversation about current events in my room.” In her response to a recent survey, she described the discussion as “REALLY AMAZING as usually we avoid hot-button issues since they are more divisive, but news literacy takes all of that out and really just focused it in on things we can all agree on.” (Suzanne asked that her last name not be used because of her district’s policy on educator interviews.)

Here is the bottom line: Every state must adopt standards that include civics or media literacy courses, with lessons on determining whether what we are reading, watching and hearing is worthy of our trust. This essential life skill can help prevent our young people from becoming locked in echo chambers or lured down rabbit holes by online extremism.

Bradley Bethel, an English teacher in Graham, North Carolina, said his — and his students’ — experience with Checkology has reinforced the critical importance of this knowledge.

“Equipped with the language to discuss the news and current events analytically, my students now rely less on their emotions, more on reason and evidence,” he said. “They have developed a shared set of norms for determining truth. If our students can bring that shared set of norms to our society more broadly, we might have a chance at renewing civility.”

Read more from this series:

- Apr. 22: Spotlight — a special resonance

- Apr. 8: The 19th* — a nonprofit news startup made for the moment

- Mar. 25: How I became a ‘pinhead’ — a news literacy lesson

- Mar. 11: Fighting the good fight to ensure that facts cannot be ignored

- Feb. 26: Students’ enduring rights to freedoms of speech and the press

- Jan 28: 13 lessons from our first 13 years

- Jan. 14: Media needs to get COVID-19 vaccine story right

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Dec. 3: Combating America’s alternative realities before it’s too late

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 29: High stakes for calling the election

- Oct. 15: In praise of investigative reporting

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news

Miller discusses media, partisan divide on ‘Washington Journal’

On C-SPAN’s “Washington Journal” today, NLP founder and CEO Alan C. Miller called on the public, the nation’s education system and news media outlets to step up and help combat the virulent spread of misinformation threatening American democracy.

John McArdle, host of the call-in show, spoke with Miller about his recent commentary on how misinformation is creating “alternative realities” for some Americans.

“I think this is one of the great existential challenges of our times. It is a question of whether facts will continue to matter,” Miller said.

During the hour-long program, callers across the nation asked Miller a wide range of questions – from baseless claims of election fraud to instances of media bias. One caller decried the lack of civics education in our nation’s schools, Miller endorsed his view. “I completely agree about the need to bring back civics, to give the next generation a grounding in American government. At the core of that should be critical thinking skills to know how to sort fact and fiction and what information to trust and share,” Miller said. “Our democracy depends on an electorate that is informed and engaged, not misinformed and enraged.”

What the media can do

Turning to questions about the media, Miller warned against painting the industry with a broad brush. He pointed out that standards-based journalism and highly partisan outlets cannot be viewed through the same lens. But he also noted that journalists need to do a better job as the nation transitions to a new presidential administration.

“I think that journalists need to double down on verification, accuracy, transparency and accountability. They need to tell the truth and call out lies and avoid false balance,” he said, calling for tough but fair coverage of President-elect Joe Biden’s administration.

While acknowledging that President Trump will remain a legitimate news story regarding his political influence and legal challenges, Miller recommended that reporters turn off their notifications of his tweets.

Personal responsibility is key

Miller encouraged viewers to be responsible news consumers and to become part of the information solution instead of the misinformation problem. “Everybody has a responsibility to look at anything we encounter, any piece of news and ask ourselves who created this, for what purpose? Is it intended to inform or divide? Is there bias? What about the bias I bring to what I’m looking at? Step back and ask yourself, ‘is this something I should trust, share and act on.’ ”

In asking the public to verify the credibility of the content they consume, he noted that fact-checking organizations can be valuable resources. ”I think the independent fact-checkers play an important role, and by and large they are credible forces for people to look to when things are in dispute,” he said. He pointed out that they do not ask the public to simply trust their conclusions. “They show their findings and the basis for their determinations and are transparent on where their funding comes from.”

And he urged the public to pledge, “false information stops with me.”

You can watch the full conversation here.

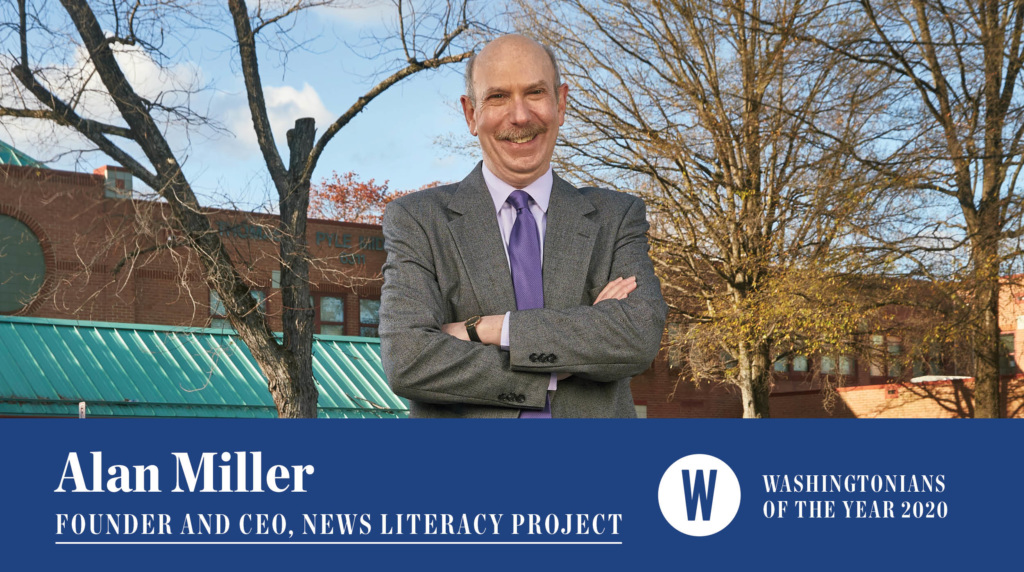

NLP founder named a Washingtonian of the Year

Photograph by Jeff Elkins

Every year, Washingtonian magazine chooses a handful of local residents “who give their time and talents to make this a better place” and names them “Washingtonians of the Year.”

NLP is proud to announce that Alan C. Miller, our founder and CEO, is a 2020 Washingtonian of the Year honoree. Below is an excerpt from the piece recognizing his achievements.

Origin story

When Pulitzer-winning LA Times reporter Alan Miller conceived of the News Literacy Project in 2006, the media — and the world — was in a different place. Facebook and iPhones were just taking off, phrases like “fake news” and “alternative facts” weren’t mainstream, and the educational field of news literacy didn’t exist. But after speaking to his daughter’s sixth-grade classmates, Miller felt it was essential to teach youth how to be “smart, active consumers of news and information”—a goal that has never felt more urgent.

“I was concerned about how they were evaluating a tsunami of information from sources with varying credibility, accountability, and transparency—and that was on a PC,” says Miller, who launched NLP, a national education nonprofit, from his Bethesda home in 2008.

‘Rigorously nonpartisan’

Those tools have come to fruition in Checkology, a free virtual-learning platform for middle- and high-schoolers that teaches how to discern credible information, bias, and misinformation. Checkology, which like NLP is “rigorously nonpartisan,” has been used by educators in all 50 states and dozens of other countries. By 2022, NLP’s goal is to reach 3 million students annually. The news-literacy mission has become even more dire in the pandemic, when discerning fact from fiction can truly be a matter of life or death.

Washington Post quotes Miller on press freedoms

The Washington Post’s Margaret Sullivan quotes Alan Miller’s column on how the U.S. can restore its global standing as a leader in press freedoms. “Bring back the daily press briefings. Make Biden available through periodic news conferences and interviews with a wide range of outlets. Tell the truth,” Miller is quoted in Sullivan’s Dec. 6 column Trump is leaving press freedom in tatters. Biden can take these bold steps to repair the damage.

Upon Reflection: ‘Kind of a miracle,’ kind of a mess and the case for election reform

Note: This column is a periodic series of personal reflections on journalism, news literacy, education and related topics by NLP’s founder and CEO, Alan C. Miller.

Amid the chaos and controversy that has marred this post-election period, let’s take a moment to celebrate some things that went indisputably right in our recent rite of democracy:

- During a devastating pandemic, more than 152 million Americans voted. This is a record and represents at least 64.4 percent of the voting-age population — which makes it the highest participation rate since at least 1908, when 65.4 percent of eligible voters cast ballots and Theodore Roosevelt was reelected president.

- Despite embarrassing breakdowns and delays in various states during primaries, the process on Election Day went remarkably smoothly nationwide.

- Fears of cyber-interference by Russia or others failed to materialize. The same was true of widespread voter harassment, voter intimidation or violence at polling places.

“This election was kind of a miracle,” Lawrence Norden, the director of the Election Reform Program at the Brennan Center for Justice, said in an interview. “We had huge turnout during a pandemic and there really weren’t the kind of problems that we had in the past.”

“Voters were the heroes,” said Marcia Johnson-Blanco, co-director of the Voting Rights Project at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. They made good use “of all opportunities to access the ballot.”

There were other civic heroes, too: the thousands of Americans who painstakingly counted ballots, many working long hours under intense scrutiny against the backdrop of sporadic protests and an escalating pandemic.

Of course, this success has been overshadowed by the excruciating counting of enough votes in a handful of battleground states to declare Joe Biden president-elect and by Donald Trump’s unsubstantiated claims that, absent widespread voter fraud, he would have won a second term.

While Trump’s refusal to concede is extraordinary, the election process itself is playing out in constitutionally mandated ways. Votes continue to be counted, as states typically have two to three weeks after Election Day to certify their totals. Courts are hearing lawsuits filed by the Trump campaign in several states. (This year the deadline for lawsuit resolution and vote certification is Dec. 8 — six days before the Electoral College meets, as required by federal law.) Recounts, which are customary in extremely close contests, are expected in a few states, though they typically result in changes too marginal to reverse outcomes. On Nov. 10, The New York Times reported that election officials of both parties nationwide said they had seen “no evidence that fraud or other irregularities played a role in the outcome of the presidential race.”

Votes, like facts, are stubborn things.

The unfolding national civics lesson has underscored the reality that the patchwork nature of our decentralized election system causes confusion and sows the seeds for disinformation. Each state decides how, when and where voters can cast their ballots; whether technical mistakes by voters (such as forgetting to sign an envelope or submitting a signature that doesn’t match the one in the voter database) can be “cured” (or fixed); and when mail-in ballots can begin to be counted.

The most striking — and damaging — disparity involves the counting of mail-in votes. As it became clear that a record number of Americans (more than 65 million) would go this route in response to COVID-19, a number of states changed their laws to avoid long delays in determining the results by enabling “pre-canvassing” (opening and organizing ballots for processing) days, or even weeks, before Election Day. Some states permit these ballots to be counted when they are received (one is Florida, which permits counting as early as 40 days before Election Day).

As the president insisted for months, without evidence, that the growing number of mail-in ballots would invite fraud, Republican-controlled legislatures in three battleground states declined to make significant changes in their timetables for counting them. Michigan revised its law to permit counting in some jurisdictions to begin only the day before Election Day; Wisconsin and Pennsylvania refused to permit counting until Election Day itself.

Gene DiGirolamo, a Republican commissioner in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, warned in September that without pre-canvassing, “we’ll be forced to contend with a man-made disaster — one that easily could be avoided.”

Sure enough, Pennsylvania, with its crucial 20 electoral votes, experienced a tsunami of mail-in votes. Because no work on those ballots could begin until the polls closed, it wasn’t until Nov. 7 — four drama-filled days later — that the networks and The Associated Press had sufficient data to call the state for Biden. Moreover, since far more Republicans voted at the polls and far more Democrats voted by mail, Trump predictably jumped out to a wide early lead, only to see Biden close in day by day until overtaking him.

This shifting public tabulation opened the door to the perception (and claims by Trump and his allies) that something nefarious was afoot — that votes mailed before Election Day were being cast afterward, or that votes were suddenly being “found” or that a conspiracy was underway to “steal” the election. This took hold among Trump supporters even as poll watchers from both parties observed the counting and Republican officials, both state and local, in Pennsylvania, Georgia and elsewhere vouched for the integrity of the process and the validity of the outcomes.

The result was corrosive — and it threatens to undermine Biden’s legitimacy with a large segment of the electorate. A Politico/Morning Consult survey conducted Nov. 6-9 found that 70 percent of Republicans said the election was “definitely” or “probably” not free and fair, primarily due to their belief that there was widespread fraud in mail-in voting. By contrast, 90 percent of Democrats said the election was free and fair.

The Constitution’s Elections Clause, which describes the rules for elections to the Senate and the House of Representatives, allows states to set their own regulations for congressional elections but gives Congress the authority to “make or alter” those regulations as necessary. Given the current changes in voting patterns and advances in technology, Congress may consider setting uniform national rules for processing and counting mail-in ballots, permitting early voting, setting the deadline for receiving ballots, and ensuring the ability to “cure” ballots that have technical errors. Congress could also provide funds to upgrade aging voting machines and improve the infrastructure for mail-in voting.

“Other democracies have figured out how to count all of the votes without distorting the results, frightening their voters or sowing discord,” Stephen I. Vladeck, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, wrote in a Nov. 8 opinion column for The New York Times. “If the last week has taught us anything, it’s that the United States should do the same.”