Jan. 6 insurrection a game-changer for news literacy educators

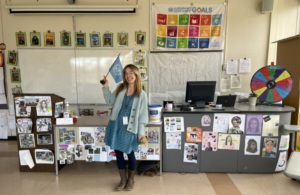

Photo credit: Molly Boyle

The insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, was a watershed moment for high school teacher Anne-Michele Boyle.

Until then, she’d spent only a few days teaching media literacy to students in her Global Citizenship course. But when she and her students watched events unfold live during remote learning, she immediately reworked her curriculum.

“I scrapped my entire lesson plan for February and devoted that month to media literacy,” recalled Boyle, who also teaches AP World History at Whitney M. Young Magnet High School in Chicago. “January sixth illustrated to me how fragile democracy is and how dangerous misinformation can be.”

After the uprising, Boyle spent months developing a full media literacy curriculum for the roughly 90 juniors and seniors in her class. She now spends all of January — and often part of February —teaching this subject.

Inundated with information

That same day in Mason, Ohio, Jocelyn Burlew was teaching seventh and eighth grade history online. As soon as her students logged in, they began asking questions about what was happening. “These questions paired perfectly with our study of the Constitution, particularly the powers of the president as well as our rights and responsibilities as we discussed the Bill of Rights,” she said.

That same day in Mason, Ohio, Jocelyn Burlew was teaching seventh and eighth grade history online. As soon as her students logged in, they began asking questions about what was happening. “These questions paired perfectly with our study of the Constitution, particularly the powers of the president as well as our rights and responsibilities as we discussed the Bill of Rights,” she said.

She, too, saw an opportunity to provide her students with a news literacy lesson in real time, noting that they were inundated with videos, memes, news stories, eyewitness accounts and more.

“We had to slow down and really start to analyze what we were seeing and hearing, and then take what we knew about the Constitution, the role of the media, as described in the First Amendment, to really start to grasp what was happening and understand the difference between types of information and how to vet it,” said Burlew, a news literacy ambassador for the News Literacy Project, who teaches in the Mason City School District in suburban Cincinnati.

She uses NLP’s educator newsletter The Sift® and the Checkology® e-learning platform to weave news literacy into her classes. “I initially used Checkology’s ‘InfoZones’ lesson to introduce my students to the various types of information they may come across. I then used these concepts in their study of ancient Athens and Sparta.”

That foundation helped them better understand the uprising and the role of a free press in a democracy. She hopes her students take away from her class the understanding “that we have to be thoughtful and critical consumers of media and hold news outlets to the standards of quality journalism.”

Students share what they learn

Photo credit: Molly Boyle

To keep her course current, Boyle forgoes a textbook and brings in new resources each year. She also uses educator resources on NLP’s website to help students build essential skills, including lateral reading, reverse image searches, evaluating sources and geolocation.

“We examine the extent to which the sources we use adhere to standards of quality journalism, why standards matter and why journalists have a lot to lose if they don’t follow those standards. We compare this to the news posts students see on TikTok,” she said.

Boyle also teaches Checkology’s “Misinformation,” “Conspiratorial Thinking” and “Understanding Bias” lessons.

As her students begin to recognize the real dangers of misinformation they can act on their knowledge. For example, as part of a final project, some students created news literacy quizzes on the game-based learning app Kahoot! for family get-togethers. They wanted to teach older relatives how to spot conspiracy theories on social media and to recognize mis- and disinformation. “They’re taking the skills they learn and reaching more people,” she said.

And she’s watched their understanding of the problem evolve. “Before we started the [media literacy] unit, most did not realize how scary January sixth was. It is essential for all people to understand the connection between having a strong democracy and strong media literacy skills.”

Personal impact

Burlew has had similar experiences. “In general, students love having the knowledge and power to debunk what they see and hear.”

And for Boyle, the insurrection also had a personal impact. A month prior she had applied to the Fulbright U.S. Scholar Program. Immediately after that day she got permission to resubmit her application with a new focus on a plan to improve media literacy. She won the fellowship.

Both educators want their students to recognize the value of their newfound skills. “First and foremost, media literacy is absolutely essential to a strong democracy. Period,” Boyle said.

Our statement on the assault on the Capitol

We deplore the violent assault on the U.S. Capitol today by a lawless mob. While we support the right to peaceful assembly and free speech guaranteed by the First Amendment, this was an anti-democratic attempt to prevent the culmination of a free and fair election.

The attack on the Congress — and the post-election events leading up to it — underscore the need for robust civics education that gives people a basic understanding of the Constitution and the fundamental principles of democracy. We call on the new Congress to appropriate funds now to achieve this goal and to protect our democracy. This must include funding for news literacy, which empowers people to discern credible information from misinformation and gives them the tools to be equal, informed and engaged participants in the country’s civic life.

Such an education is essential to bridging the deep partisan divide and alternative realities that have driven our democracy to such a dangerous place.

Upon Reflection: Combating America’s alternative realities before it is too late

Note: This column is a periodic series of personal reflections on journalism, news literacy, education and related topics by NLP’s founder and CEO, Alan C. Miller.

Donald Trump’s presidency began with the concept of alternative facts. It is ending with a country divided by alternative realities.

In the intervening years, the fault lines in America have deepened. They are defined by demographics and geography and partisanship. But they are driven by all of the information, including news, that we consume, share and act on.

When I was a reporter, journalists would bring out the old phrase “Facts are stubborn things” as an ironic way of complaining when an inconvenient fact proved to be the undoing of what would otherwise have been a good story. Today, it is opinions that are often impervious to facts.

For many, trust in institutions, including the media, has ruptured. Facts are no longer convincing; feelings hold sway, and conspiratorial thinking has moved into the mainstream. But don’t blame Donald Trump for this. While he has exploited and accelerated this erosion of fact-based reality, it didn’t start with him.

Nor is this tendency to disregard evidence and expertise a purely partisan exercise. The anti-vaxxer movement includes many progressives; in fact, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is one of its most prominent leaders.

Yet there is no doubt that the inclination to disregard credible sources and verifiable information in favor of unproven assertion and surreal supposition has intensified since Trump became president — aided by the right-wing media echo chamber and the cauldron of toxic misinformation on social media. Consider these three stunning developments this year alone:

- Even as a global pandemic has resulted in almost 14 million cases of COVID-19 and more than 273,000 deaths in the United States alone, many people still believe that the disease is a hoax or has been exaggerated for nefarious purposes. A nurse in South Dakota recently told CNN that some of her patients, even as they got sicker and sicker, remained convinced that the virus was fake. Their dying words, she said, were, “This can’t be happening. It’s not real.”

- The conspiratorial delusion known as QAnon holds that a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles — including prominent celebrities and Democratic politicians — are secretly running the government and engaging in child sex trafficking, and that Donald Trump is the only person who can stop them. Polls show that a growing number of Americans are open to this dangerous apocalyptic thinking, and two QAnon supporters— Georgia Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene and Colorado Republican Lauren Boebert — will be sworn in next month as members of the U.S. House of Representatives.

- Trump has claimed, without producing any evidence, that he won the presidential election in a landslide and that it was stolen by Joe Biden through widescale fraud. Members of the president’s legal team — including his personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani — have floated wild and baseless conspiracy theories involving living and dead Venezuelan leaders, a Canadian company that makes electronic voting machines and a computer server in Germany. Dozens of lawsuits filed by the Trump campaign in battleground states have been dismissed; Republican officials in those states have helped oversee recounts and certify the votes. Nevertheless, a Monmouth University survey found that 77% of Trump voters — that’s 56 million Americans — believe that Biden won through fraud.

It is now nearly impossible to avoid the contagion of viral rumors and corrosive mistrust. Before the election, my daughter said she heard that voting by mail “isn’t safe.” My mother said she was skeptical that Trump had really come down with COVID-19. And after the vote, my 6-year-old granddaughter said a classmate told her, “Biden cheated to win the election.” (Lyla said she set him straight.)

It’s time to confront this rising tide before it is too late. We just endured a stress test of democracy, and the guardrails held. But if we do not work together to assure a future founded on facts, we may not be as fortunate next time.

Here are some things that we can — and must — do now:

The news media: Double down on accuracy, verification, transparency and accountability. Call out lies. Avoid false balance. Be tough but fair in covering the Biden administration. Report on Trump as a political, legal and media story, but turn off your notifications of his tweets.

Cable news networks: Dial back on the partisanship and the chatter. Rachet up the reporting.

Social media companies: Consistently and vigorously enforce your community standards against hate speech and other language that incites violence and damages public health and democracy. Boot anyone who routinely violates them off your platform. Improve your algorithms to elevate credible information.

Congress: Sensibly regulate social media companies to ensure that they comply with their standards, protect consumer privacy and do not undermine democracy.

The Biden administration: Bring back the daily press briefings. Make Biden available through periodic news conferences and interviews with a wide range of outlets. Tell the truth. Do not repeat the Obama administration’s mistake of opposing the release of public information and cracking down on government leaks. Restore America’s place in the world as a leading proponent of press freedom.

The education system: Bring back civics lessons — including, as an essential component, teaching students how to separate fact from fiction and determine what information they can trust. Incorporate media literacy and news literacy programs across multiple disciplines in middle schools and high schools nationwide.

The public: Become more mindful about what you read, watch and hear; more skeptical of what you trust; and more responsible with what you share. Consume a varied news diet, and practice good information hygiene. Push back against misinformation, and reach out empathetically to those who are spreading it.

Facts: Hold on tight. You deserve at least a fighting chance. You are too important to fail.

Read more in this series:

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 29: High stakes for calling the election

- Oct. 15: In praise of investigative reporting

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news

From the Sift®: Understanding misinformation in the wake of the election

Misinformation and conspiracy theories thrive when curiosity and controversy are widespread and conclusive information is scarce or unavailable. The deeply polarized 2020 presidential election not only produced these conditions, it sustained them as ballots in a number of swing states with narrow vote margins were adjudicated and carefully counted.

To be sure, viral rumors swirled in the aftermath of Election Day. People who had been primed by partisan rhetoric to expect voter fraud leaned into their own biases. They misinterpreted isolated moments on livestreams of the ballot counting process in counties in several swing states, mistakenly saw “evidence” of rogue ballots being delivered in vague video clips, and were exploited by bad actors who readily circulated staged, manipulated and out-of-context content designed to mislead.

But the impact of these falsehoods was blunted by the work of professional fact-checkers, disinformation researchers and standards-based news organizations — and by social media platforms, which improved their content moderation efforts for the election. Facebook and Twitter took more effective actions against misinformation than either had previously. (However, Twitter indicated that with the election over, it would stop using warning labels on false or misleading tweets about the election outcome but continue its use of labels that provide additional context.) YouTube was more lax, allowing videos containing false claims about the election — including those that it acknowledged undermine trust in the democratic process — to remain live but without ads.

The days of uncertainty sparked isolated protests and some arrests, including two armed Virginia men. But for all the unresolved questions and still-rampant falsehoods, it seems, at least so far, that the worst-case scenarios were averted, even in an otherwise historic election with record turnout.

Related:

- “Here’s A Running List Of False And Misleading Information About The Election” (Jane Lytvynenko and Craig Silverman, BuzzFeed News).

- “Twitter and Facebook warning labels aren’t enough to save democracy”(Geoffrey A. Fowler, The Washington Post).

Note: Misinterpreting videos of the vote counting process at locations across the country is a textbook example of confirmation bias.

KGTV in San Diego talks conspiracy theories with NLP’s Silva

NLP’s John Silva was interviewed by KGTV in San Diego on Nov. 5 for the segment “We don’t like this idea of being uncomfortable that there’s some big thing that we’re not aware of. In the discomfort and the anxiety of not knowing, we might accept [the false information],” he says in order to explain the appeal of conspiracy theories and viral rumors about the 2020 election.

Adams quoted in two high-profile outlets day before 2020 election

On Nov. 2, the day before the historic 2020 election, NLP’s Peter Adams is quoted in the MIT Technology Review piece How to talk to kids and teens about misinformation and in the New York Times piece Stopping Online Vitriol at the Roots.

Upon Reflection: High stakes for calling the election

Note: This is the third in a periodic series of personal reflections on journalism, news literacy, education and related topics by NLP’s founder and CEO Alan C. Miller.

As Election Day nears, Democrats are haunted by the media-driven sense of inevitability that Hillary Clinton was headed to a historic victory four years ago — until she wasn’t.

Voters may also recall television networks declaring Al Gore the winner in the battleground state of Florida in 2000 — only to rescind that call hours later. The next day, the networks prematurely called George W. Bush the winner — only to see the subsequent recount of Florida ballots stretch 37 days, until it was resolved in Bush’s favor by the Supreme Court.

This year, the landscape is far more complex and combustible than it was during those two hotly contested races. This is a watershed moment for American journalism — and particularly for the networks and The Associated Press, which also calls election outcomes. The stakes for democracy are sky-high.

In the face of commercial and competitive forces, it is imperative that anchors, reporters, producers, editors and news executives exercise restraint, precision and care with any results they project and races they call, and that they are open about their process for doing so. They need to provide contextual reporting and analysis, explaining that delay does not necessarily signal dysfunction and careful counting does not automatically suggest corruption. And they must prepare the public for a more protracted — yet constitutional — process for determining the outcome of this contest.

America is now far more polarized than it was in 2016, when Donald Trump lost the popular vote but won the Electoral College. Trust in institutions, including the news media, has declined. The country is restive amid a devastating pandemic, protests for racial justice and the growing power of baseless conspiracy theories.

Two factors could make projecting and counting this year’s balloting more challenging: historically high voter turnout and a record number of mail-in votes that, for the first time, may outnumber those cast in person. They also increase the prospect that the winner will not be known on Nov. 3.

Moreover, both parties have expressed doubts about the legitimacy of the process: Trump has repeated baseless charges that mail-in voting opens the door to widespread fraud, which his opponents say is intended to sow doubt if the president is declared the loser or faces that prospect when all the votes are counted. Democrats have expressed concerns about voter suppression and intimidation. Both issues are likely to be highly charged currents in the election narrative.

In preparing this column, I asked CNN, Fox News, NBC News, ABC News, CBS News and The Associated Press what they are doing differently this year. (Only CNN failed to respond.)

They said they are training, going through drills and preparing for myriad contingencies. They vowed to be deliberative, restrained and transparent about projecting and calling races. Some said they have expanded their teams and plan to tap more reporters on the ground in key states and more experts on American history, election law and constitutional law. Others promised new video walls, data visualization tools and augmented reality to help voters better understand the process.

In the aftermath of the 2016 embarrassment, at least some have upgraded their process for projecting results.

Two years ago, recognizing that voting patterns have changed, Fox News and The Associated Press collaborated with NORC — an independent research center at the University of Chicago — on a survey that Fox News calls Voter Analysis and the AP calls VoteCast. NORC describes it as “a probability-based state-by-state survey of registered voters combined with a large opt-in survey of Americans conducted online.” Fox says that this year, it will interview 100,000 voters and non-voters prior to, and on, Election Day; the AP says the sample size is “more than six times the size of the legacy exit poll.”

NBC News, which shares its data with MSNBC, says it will also rely on information from interviews with more than 100,000 voters that began on Oct. 13. It has expanded both its in-person early exit polls and its phone polling this year. CBS News says that it, too, will have surveyed 100,000 people from all 50 states by election night.

I recommend paying special attention to Fox News and the AP on election night. Given its influential and supportive coverage of Trump, particularly by its evening opinion hosts, Fox could play an outsize role. The Fox News decision desk, led by Arnon Mishkin, is widely respected for its professionalism and independence.

(You may recall the unusual scene on election night in 2012 when Mishkin stood his ground when GOP strategist Karl Rove insisted, on air, that Mishkin had called Ohio — and thereby the presidential race — too soon for President Obama.)

In its statement to me, Fox News described “the integrity of our Decision Desk” as “rock solid. We will call this presidential election carefully and accurately, relying on data and numbers.”

The AP is continuing its historic practice of not projecting winners; instead, it announces them only when it has determined there is no way for the trailing candidate to catch up. Notably, the wire service did not call Trump’s victory until 2:29 a.m. on election night in 2016 and did not call the race for either Gore or Bush in 2000 (or call a winner on election night in 2004 and 2012).

Lacking sufficient tallies and other information to declare an unofficial winner on election night, the networks will need to remind viewers that each state has deadlines for certifying their vote (typically two to three weeks after Election Day) and they have until Dec. 8 to settle post-election legal challenges. In addition, 21 states and the District of Columbia have automatic recounts if the margin of victory is below a certain number or percentage or if there is a tie.

“The networks are extremely aware of the many problems they might be confronting,” Jeff Greenfield, a longtime broadcast journalist and media analyst, told me. “Nobody in the media has any interest in throwing gasoline on a fire.”

For democracy’s sake, let’s hope he’s right.

Read more in this series:

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Dec. 3: Combating America’s alternative realities before it’s too late

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 15: In praise of investigative reporting

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news