Maria Ressa, fierce defender of journalism, receives Nobel Peace Prize

In 2020, she was a guest on NLP’s podcast, Is that a fact?

The News Literacy Project (NLP) offers its congratulations to 2021 Nobel Peace Prize winners Maria Ressa, the founder of the media company, Rappler, who has fearlessly confronted violent authoritarian rule in the Philippines, and Dmitry Muratov, a founder of of Russia’s independent newspaper, Novaya Gazeta, which provides fact-based reporting on controversial topics other Russian media rarely cover.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee is honoring Ressa and Muratov “for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.” In announcing the prize, the committee recognized “their courageous fight for freedom of expression in the Philippines and Russia. At the same time, they are representatives of all journalists who stand up for this ideal in a world in which democracy and freedom of the press face increasingly adverse conditions.”

“Ressa and Muratov exemplify the vital role that journalists are playing throughout the world in holding the powerful accountable in the face of serious risks to their own freedom and safety,” said Alan Miller, the founder and CEO of NLP. “We applaud the Nobel committee for recognizing these profiles in journalistic courage.”

Speaks with NLP about journalism and authoritarian rule

In 2020, Ressa addressed the question “Can journalism survive an authoritarian ruler?” as a guest on NLP’s new podcast Is that a fact? During that interview, she spoke about how social media feeds narrow our view of the world and give legitimacy to falsehoods, propaganda and conspiracy theories.

“This is how you create alternate realities,” she said. “That’s the world we live in today… it’s important that we really understand that social media has changed the information ecosystem globally. What it’s done now is that it’s become part of the dictator’s playbook because a lie told a million times can become a fact.

“And with micro-targeting, it takes our most vulnerable moment to a message and sells it to the highest bidder, whether that is a government or whether that’s a company, anyone who pays for it, right? And that is alarming to me because journalists can’t even do our jobs if we all don’t agree on facts. If you don’t have facts, you can’t have truth. If you don’t have truth, you can’t have trust. Without any of these three things, you can’t have democracy.’

Listen to the full interview.

Criticism of Facebook

Ressa has been a vocal critic of Facebook, which the administration of Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte has used as a powerful propaganda tool. “Facebook is now the world’s largest distributor of news and yet it has refused to be the gatekeeper. And when it does that, when you allow lies to actually get on the same playing field as facts, it taints the entire public sphere,” she said in a 2019 interview with The New York Times.

She continues to uphold the highest standards of journalism and push back against Duterte’s regime, despite being arrested and jailed and becoming the target of multiple death threats. Ressa has personally experienced how hard it is for journalists to hold the line against an authoritarian leader when press freedoms are threatened.

For decades, Muratov has fought for freedom of speech and professional ethics and standards of journalism under worsening conditions, harassment, threats and violence. Six journalists at Novaya Gazeta have been killed since its founding nearly three decades ago.

Upon Reflection: Supporting journalists serving local communities of color

Communities of color have historically been underserved by the news business, and the loss of journalism jobs and outlets nationwide has exacerbated this neglect. Then came the pandemic, with its disproportionate impact on Black and brown people throughout the United States, and the accompanying “infodemic” of misinformation.

Photo credit: Daniel Robles

In early 2020, Maritza Félix saw this neglect — and the resulting lack of trustworthy information in these communities — as an opportunity to fill a need. The 38-year-old freelance journalist and self-described “WhatsApp queen” decided to use that social media platform to connect people in Arizona and Sonora, Mexico, with a Spanish-language service that would combat harmful misinformation and provide practical, credible “news you can use.”

Conecta Arizona has succeeded beyond her wildest dreams. She has engaged 50 experts on health, immigration, personal finances, and other topics to provide guidance to the 257 participants in her WhatsApp group (the maximum size of a WhatsApp group is 256, plus an administrator). She has done 265 online “horas del cafecito” (coffee hours), and is writing a weekly column for Prensa Arizona, the state’s largest Spanish-language newspaper. On Feb. 4, she started a weekly program, La Hora del Cafecito en la Radio, broadcast on a Phoenix radio station and online.

“We are building a model to strengthen local journalism that inspires others to do the same in their communities,” she wrote in a May 11 post on Medium, adding: “I didn’t want to change the world, but I did want to save it from a pandemic of misinformation.”

Félix is one of 11 journalists who last week completed their eight-month John S. Knight Community Impact Fellowships, based at Stanford University but conducted remotely. Spurred by both pandemic-imposed restrictions on residential sessions and a heightened sense of urgency about the lack of diversity in newsrooms, the Community Impact Fellowship program was created last year to nurture resilient leaders, like Félix, who serve communities of color with early-stage journalism initiatives. These initiatives are seedlings of new life amid the withering nationwide losses in local journalism.

(Full disclosure: The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, which funds the JSK Fellowships, is one of the News Literacy Project’s largest donors.)

On the final day of the program, I spoke with Félix and another JSK fellow, Candice Fortman, the executive director of Outlier Media. It provides Detroit residents with information about public services and other needs via text and collaborates with local partners on news reporting. I was struck by the impact that Félix and Fortman and their service-oriented models are having on often-overlooked communities. I was also impressed by the JSK Fellowships’ strategic pivot to reframe its program for mid-career journalists, founded in 1966, as Community Impact Fellowships.

The pandemic presented an opportunity to focus on individuals who were “doing journalism for the community and in the community,” Dawn Garcia, the veteran JSK Fellowship director, told me. The need to deliver the program remotely allowed participants to continue to provide essential services locally while using Zoom to join the fellowship’s workshops and its coaching, brainstorming and networking sessions.

For Félix, the fellowship provided funding to help her sustain her experiment — and something far less tangible, but just as vital.

Since arriving in the United States from her native Mexico 15 years ago, she has become an acclaimed journalist: In 2012 and 2013, the Phoenix New Times named her the best Spanish-language journalist in Arizona, and she won five Emmy Awards during three years as a writer and producer at Telemundo. Still, she said, being selected for the JSK Fellowship was deeply validating.

“They bet on a Latina, an immigrant with red lipstick, a hand-embroidered Mexican blouse, and a strong accent,” she wrote on Medium. “It was as if I had been a seed and thrown into fertile ground … and I flourished.”

Indeed. “In one year,” she wrote, “we have answered 1,214 questions from members of our community, plus the 511 we answered during the intense election coverage in 2020.” In addition, she continued, “we have debunked 262 conspiracy theories, myths, and fake news from social media.”

Félix has just started a newsletter and has plans for a website. She aspires to be able to pay Spanish-speaking journalists for stories, she said — but “first, I need to pay myself.” And she hopes that she will be able to develop a sustainable business model that does not rely entirely on philanthropy.

Outlier Media is creating just such a model.

It was founded by Sarah Alvarez, a former public radio reporter and producer who developed the concept as a JSK fellow in 2016. Outlier, a nonprofit, creates beats for its five-person staff based on the stated needs of its low-wealth community. When the pandemic hit, Fortman said, those needs included responses to food insecurity and child-care concerns, along with actionable information about COVID-19.

In addition to texting information directly to residents in both English and Spanish, Outlier’s reporters work collaboratively with many of the newsrooms in the city on watchdog and investigative reporting. One reporter, shared with the Detroit Free Press, translates Outlier’s texts into Arabic. (The Detroit area is home to one of the country’s largest Arab American communities.)

Outlier was bolstered this year by a three-year, $950,000 grant from the American Journalism Project, which supports new models in local nonprofit journalism. Fortman said the funds would be used to help increase and diversify revenue through such sources as consulting, sponsorships, corporate gifts, events and merchandising.

“We are a blank canvas on which to build our model: a new way for newsrooms to build relationships with communities and not on the backs of communities,” she wrote in a Dec. 2 Medium post.

Fortman told me that her biggest takeaway from the JSK Fellowship is her realization that “collaboration is likely the best route forward for most of us.” This may include partnering with other outlets to share the cost of development, information technology and other specialized services.

What else will it take for innovative outlets like Outlier Media and Conecta Arizona to succeed?

It starts with listening to the community — first to determine its needs and then to figure out how best to meet them through a two-way conversation. It requires using technology in creative and sometimes experimental ways. A sound business model and diverse revenue sources are critical for long-term sustainability.

Above all, it means nurturing committed journalists-turned-social entrepreneurs like Félix, Alvarez and Fortman, and investing in their vision.

“I took a step back in my journalism and realized why I started in the first place: to serve the community, to serve my people,” Félix told me. “I don’t need to be working with a big production company. Sometimes you can make a difference with very small things, like we’re doing.”

We should all root for these initiatives to succeed with impactful and sustainable models that others can emulate. If they do, they can help rebuild local news, restore trust in journalism and reach diverse communities that have long felt ignored. That would be no small thing.

Correction: An earlier version of this post stated Maritza Felix’s age as 34. She is 38.

Read more from this series:

- Apr. 8: The 19th* — a nonprofit news startup made for the moment

- Mar. 25: How I became a ‘pinhead’ — a news literacy lesson

- Mar. 11: Fighting the good fight to ensure that facts cannot be ignored

- Feb. 26: Students’ enduring rights to freedoms of speech and the press

- Feb. 11: We need news literacy education to bolster democracy

- Jan 28: 13 lessons from our first 13 years

- Jan. 14: Media needs to get COVID-19 vaccine story right

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Dec. 3: Combating America’s alternative realities before it’s too late

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 29: High stakes for calling the election

- Oct. 15: In praise of investigative reporting

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news

Behind the headlines: Blocking press freedoms

This article is from a previous issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

By Suzannah Gonzales

Journalism — “arguably the best vaccine against the virus of disinformation” — is obstructed in a majority of countries around the world, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and its new press freedom ranking.

The 2021 World Press Freedom Index, an annual ranking of 180 countries and territories, showed that journalism “is totally blocked or seriously impeded in … 73% of the countries evaluated.” The “data reflect a dramatic deterioration in people’s access to information and an increase in obstacles to news coverage,” an overview of the ranking said. COVID-19 is being used to block availability to sources and reporting on the ground, making it hard to cover controversial stories. RSF questioned whether access will improve once the pandemic ends.

In addition, RSF noted a troubling measure of public mistrust of journalists, citing the results of a survey in 28 countries called the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer. It found that nearly 60% of those who responded believe “journalists deliberately try to mislead the public by reporting information they know to be false” when in actuality, journalism combats “infodemics” of misinformation and disinformation, RSF said.

The United States advanced one place (to 44) with its press freedom categorized as “fairly good,” RSF said, despite unprecedented numbers of assaults against and arrests of journalists (about 400 and 130, respectively).

Norway remained at the top of the list for the fifth year, and Finland held on to its second-place spot while Sweden reclaimed its third-place ranking. Totalitarian countries once again claimed the bottom three places — Turkmenistan (178), North Korea (179) and Eritrea (180). Malaysia, which recently enacted a law against what authorities deem false content, dropped the most in the ranking — 18 spots to 119.

Related:

- “Governments are using Covid-19 as an excuse to crack down on press freedom” (Sara Torsner and Jackie Harrison, Nieman Lab).

- “Guilty Verdict for Hong Kong Journalist as Media Faces ‘Frontal Assault’” (Austin Ramzy and Tiffany May, The New York Times).

- “Very telling/chilling response by Hong Kong government to latest RSF press freedom rankings” (Timothy McLaughlin, Twitter).

- “Listening to what trust in news means to users: qualitative evidence from four countries” (Reuters Institute).

Upon Reflection: Spotlight — a special resonance

This column is a periodic series of personal reflections on journalism, news literacy, education and related topics by NLP’s founder and CEO, Alan C. Miller. Columns are posted at 10 a.m. ET every other Thursday.

Photo Credit: Spotlight, Participant Media/Open Road Films, 2015

The upcoming Academy Awards ceremony on Sunday offers an opportune moment to reflect on my favorite film about journalism: Spotlight, which won the best picture Oscar in 2016.

The movie — whose title comes from the name of The Boston Globe’s investigative team — depicts how reporters and editors at the paper uncovered decades of sexual abuse by local Roman Catholic priests and the Boston Archdiocese’s role in covering it up.

More than five years after its release, it continues to resonate with me for deeply personal reasons. I spent most of my 29 years as a newspaper reporter doing the kind of dogged, challenging and impactful investigative work that Spotlight captures with such painstaking authenticity. This gave me a particular appreciation for the lengths to which the filmmakers went to get it so right — and how they were able to make such an engrossing and entertaining movie in the process.

Moreover, it brought attention to journalism’s watchdog role — holding the powerful accountable — and the importance of a local newspaper to its community at a time when journalism was increasingly under fire and many local publications were failing. It portrayed the reporters and editors as heroic, though fallible, and reflected the essential role of principled sources and courageous victims to bring vital, if excruciatingly painful, truths to light.

In addition, I have a unique connection to this movie: Marty Baron (powerfully portrayed by Liev Schreiber), who set the investigation in motion on his first day as the Globe’s top editor and oversaw it with steely determination, is a friend and former colleague. For months, I shared in his excitement as he told me about the film’s production and launch.

I first saw Spotlight in 2015 at an investigative journalism film festival that featured a discussion with Baron, some of his former Globe colleagues, director Tom McCarthy and McCarthy’s co-screenwriter, Josh Singer. I sat between two longtime friends — Chuck Lewis, the founder of the Center for Public Integrity and the executive editor of American University’s Investigative Reporting Workshop, and James Grimaldi, an investigative reporter at The Wall Street Journal and a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner.

Throughout the screening, the three of us shared chuckles of recognition — when reporter Michael Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo) first makes his edgy inquisitiveness felt; as Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams) and her colleague traipse from door to door in Boston’s blue-collar neighborhoods in search of victims who will share their stories; and as the Spotlight team members scour yellowing clips in the newspaper’s library (the morgue, in newsroom parlance) and pore over records on microfilm.

During the panel discussion and in conversations at a reception following the screening, I was struck both by McCarthy’s and Singer’s abiding belief in the power of journalism and by their own relentless reporting to uncover the story behind the story.

This included a half-dozen trips to Boston to interview not just the Globe journalists, but also the attorneys and sources who contributed to the paper’s investigation. Before Baron left Boston to begin his brilliant eight-year tenure as executive editor of The Washington Post in 2013, Singer sought him out yet again.

“I have nothing more to tell you,” Baron told him. “I’m tapped out.”

Most impressively, it was the screenwriters who unearthed a 1993 newspaper report that is the linchpin for one of the film’s most compelling scenes.

In the movie, an attorney for multiple victims of sexual abuse tells members of the Spotlight team that he had informed the paper nearly a decade earlier about accusations against 20 priests in the Boston Archdiocese. He said the paper buried the story in the Metro section and never followed up. Pfeiffer later finds the story and shares it with the head of the Spotlight team, Walter “Robby” Robinson (Michael Keaton), leading the journalists to reflect on their own culpability in not previously unearthing the Archdiocese’s pervasive pattern of simply transferring accused priests to a new parish.

In reality, McCarthy and Singer were the ones who found that story, tucked in the Globe’s clip files, after talking to the attorney, Roderick MacLeish Jr. They presented it to Robinson, who had been Metro editor when it was published. “He was stunned,” Baron recalled in a 2016 event at American University. “He didn’t remember the story.”

There is another reason that Spotlight remains special to me.

In 2003, as the Globe continued to publish reports revealing the vastly greater scope of abuse by priests (the film covers the reporters’ actions leading up to the paper’s initial story in January 2002, with some dramatic license), a colleague and I at the Los Angeles Times were investigating another long-untold story involving another highly respected institution.

Through hundreds of interviews and thousands of pages of documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, Kevin Sack and I documented how the Marine Corps’ Harrier jump jet, which can take off and land vertically, had been, for decades, the most dangerous plane in the U.S. military for noncombat accidents. Crashes destroyed more than a third of the fleet, and 45 pilots, including some of the Marines’ finest, were killed.

We tracked down survivors of all 45 pilots, interviewing widows, fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters and creating a virtual memorial wall to honor those who paid the ultimate price in a plane that pilots called “the widow-maker.” As our four-part series, “The Vertical Vision,” revealed, this was the first of three aircraft for which the Marines would pay an enormous price in blood and treasure with minimal distinctive benefit in combat.

On May 29, 2003, Sack, our editors and I were deeply honored to join Baron and the Spotlight team and the other winners of that year’s Pulitzer Prizes at an awards lunch at Columbia University in New York City. The Spotlight team won the Public Service prize; ours was for National Reporting.

Nearly 13 years later, I found myself rooting for McCarthy and Singer — and, by extension, Baron and the Globe team — as I watched the Academy Awards. It was thrilling to see the presentations begin with McCarthy and Singer honored for best screenplay and culminate with Spotlight’s award for best picture.

In accepting the screenwriting award, McCarthy, as usual, found just the right words.

“We made this film for all the journalists who have and continue to hold the powerful accountable,” he said. “And for the survivors whose courage and will to overcome is really an inspiration to all.”

Alan C. Miller is the founder and CEO of the News Literacy Project. He was a reporter for the Los Angeles Times for 21 years. Marty Baron worked at the paper for 17 years.

Read more from this series:

- Apr. 8: The 19th* — a nonprofit news startup made for the moment

- Mar. 25: How I became a ‘pinhead’ — a news literacy lesson

- Mar. 11: Fighting the good fight to ensure that facts cannot be ignored

- Feb. 26: Students’ enduring rights to freedoms of speech and the press

- Feb. 11: We need news literacy education to bolster democracy

- Jan 28: 13 lessons from our first 13 years

- Jan. 14: Media needs to get COVID-19 vaccine story right

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Dec. 3: Combating America’s alternative realities before it’s too late

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 29: High stakes for calling the election

- Oct. 15: In praise of investigative reporting

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news

Upon Reflection: The 19th* — a nonprofit news startup made for the moment

I first met Emily Ramshaw at a dinner in Austin, Texas, in November 2019. She had just left The Texas Tribune, where she was its highly respected editor-in-chief, to take a giant leap of faith.

She was about to launch a nonprofit online news organization devoted to covering politics and policy through a gender lens, with a particular focus on women from historically marginalized communities — a perspective that she believed was sorely missing in American journalism.

We made plans to meet again in Austin in March, during South by Southwest, but as pandemic-driven lockdowns were imposed across the nation, the festival was canceled. Ramshaw and her colleagues, who had released details about their new newsroom at the end of January, saw their fundraising plummet and their ambitious plans jeopardized by the uncertainty suddenly gripping the world.

“We were in dire straits,” Ramshaw recalled when we spoke last week. “If a news organization launches in a pandemic, does anybody notice?”

She, co-founder Amanda Zamora and their team considered postponing operations for a year, but decided that the pandemic was going to disproportionately affect the very communities they wanted to focus on. With a fresh infusion of cash from two major funders as “a security blanket,” Ramshaw said, “we went for it. And thank God we did.”

In the past year, The 19th* has rocketed onto the national stage. In the process, it has tapped into the zeitgeist in a way that Ramshaw and Zamora could have neither planned nor foreseen.

(The name comes from the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted women the right to vote a century ago; the asterisk, the news organization’s website explains, “is a visible reminder of those who have been omitted from our democracy.”)

As more than 2,000 local newspapers in the United States have closed in the past 15 years and many others have trimmed their staffs, nonprofit newsrooms like The Texas Tribune and The 19th* have emerged as new journalistic models. While they have by no means filled this critical void, they do provide valuable coverage of specific cities, regions and interests.

The 19th*’s initial year was more eventful than most. As issues and opportunities arose, it broke ground and broke news.

On May 11, two weeks before George Floyd’s death led to massive protests for racial justice, it was the first national news outlet to write about the fatal shooting of Breonna Taylor by Louisville, Kentucky, police, elevating both the incident and the news organization. This report (which also appeared in The Washington Post, a news partner) was, Ramshaw said, “a breakout moment for us.”

On Aug. 3, its examination of the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on women — “America’s first female recession” — was published on the front page of USA Today. The next week, editor-at-large Errin Haines, the author of the Breonna Taylor piece, landed the first interview with Sen. Kamala Harris after Harris was selected by Joe Biden as the Democrats’ vice presidential candidate — the first African American and Asian American woman to hold that position.

Then there were the opportunities, Ramshaw said, “to make lemonade out of lemons.”

A formal launch event planned at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia in August was scrapped because of pandemic restrictions. Instead, it became a five-day “virtual summit” featuring, among others, Hillary Clinton, Stacey Abrams, Melinda Gates and Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex, along with performances by the New York Philharmonic, Meryl Streep, Zoë Saldaña and The Go-Go’s, the pioneering all-woman band.

“Suddenly, we didn’t have 500 people in a museum ballroom,” Ramshaw said. “We had about 200,000 people tuning in” worldwide.

This higher profile, combined with timely journalism and an expanded and talented staff, has paid dividends. After raising $6.67 million in 2020, Ramshaw and her team were able to increase their budget by 50% this year. Four-fifths of that fundraising total came from foundation and individual gifts; the balance was nearly evenly divided between corporate underwriting of events and membership subscriptions. Most impressively, they exceeded their first-year goal of 1,000 paying members nearly tenfold, at rates starting at $5 a year. (Full disclosure: I was one of them.)

The 19th* is also producing a steady stream of quality journalism and making it widely available. It has gone from publishing once weekly to daily or close to it, and averages 12 to 15 stories a week. Its journalism is free to consumers and free for other outlets to republish; it has partnered with the USA Today Network, which includes more than 260 daily news platforms, Univision, which is translating and distributing its reporting in Spanish. Other news organizations can pick up pieces from The 19th*’s site.

“It’s just been the most magical year, probably under the most difficult circumstances imaginable,” Ramshaw said. She hasn’t even met most of her 26-member team in person, she said — not to mention missing the camaraderie and collaboration of working together in a newsroom.

Meanwhile, The 19th* continues to evolve. Ramshaw pointed to the decision at the start of this year to include the LGBTQ+ community in its mission. “One thing we learned in our inaugural year is that women aren’t the only people marginalized based on their gender,” she said.

She and her colleagues also revised the organization’s values statement by dropping the word “nonpartisan” as an aspirational standard and replacing it with “independent.”

“The aim was to say we think the term ‘nonpartisan,’ in many ways, has been co-opted to mean bothsidesism or equal time,” Ramshaw said. “We want to be absolutely clear that we emphasize the veracity of facts and truths. Our storytelling is rooted in evidence and science and fact. And we won’t be uncomfortable in calling truth ‘truth’ and lies ‘lies.’”

The 19th* may be a hard act to follow, but its breakout success still offers lessons for others in the nonprofit journalism space:

- Start with a clear vision and sense of mission.

- Set high standards for the journalism, including independence and a commitment to fact-based storytelling.

- Enroll established partners that will share and amplify your work.

- Create diverse revenue streams and, ideally, enlist deep-pocketed donors who can step up in a pinch.

And, when the world seems to turn upside down, find a way to make lemonade out of lemons.

Read more from this series:

- Apr. 22: Spotlight — a special resonance

- Mar. 25: How I became a ‘pinhead’ — a news literacy lesson

- Mar. 11: Fighting the good fight to ensure that facts cannot be ignored

- Feb. 26: Students’ enduring rights to freedoms of speech and the press

- Feb. 11: We need news literacy education to bolster democracy

- Jan 28: 13 lessons from our first 13 years

- Jan. 14: Media needs to get COVID-19 vaccine story right

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Dec. 3: Combating America’s alternative realities before it’s too late

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 29: High stakes for calling the election

- Oct. 15: In praise of investigative reporting

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news

Behind the headlines: Sexism in journalism

This article is from a previous issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

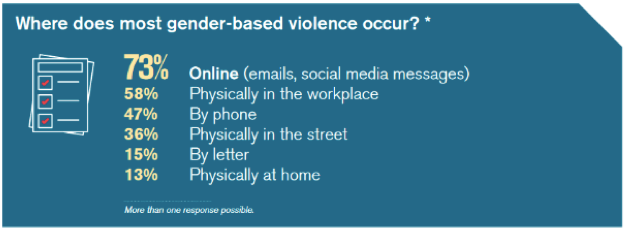

Women working as journalists increasingly face gender-based violence outside of their newsrooms, including a barrage of threats and hate online. But they also endure it inside their workplaces, from discrimination to sexual assaults and harassment, according to a new Reporters Without Borders (RSF) report detailing the toll sexism has taken on journalism.

“The two-fold danger to which many women journalists are subjected is far too common, not only in traditional reporting fields as well as new digital areas and the Internet, but also where they should be protected: in their own newsrooms,” the report said.

Reporters Without Borders “Sexism’s Toll on Journalism” report, March 8, 2021

Published on March 8 — International Women’s Day — the report includes RSF’s analysis of 112 responses to questionnaires sent to its global correspondents and journalists who cover gender, and collected between July and October 2020.

The trauma female journalists experience due to violence both in and out of the newsroom silences victims and leads some to close their social media accounts or even resign, the report found. Issues affecting women “become invisible” in news coverage when there aren’t enough women in top leadership positions, the report said: “The lack of multiple viewpoints within media organisations has major editorial consequences, including in the representation of women in the content offered to the public.”

Note: A separate March 8 report by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism revealed that 22% of top editors at 240 major news organizations are women.

Related:

- “New York Times Defends Reporter Taylor Lorenz From Tucker Carlson’s ‘Cruel’ Attack” (Jordan Moreau, Variety).

- “Carlson, Times tussle over online harassment of journalist” (David Bauder, The Associated Press).

- “Maria Ressa: Fighting an Onslaught of Online Violence” (International Center for Journalists).

- “UNESCO launches campaign to end online violence vs women journalists” (Rappler).

- “Malign Creativity: How Gender, Sex, and Lies are Weaponized Against Women Online” (Wilson Center).

Upon Reflection: How I became a ‘pinhead’ — a news literacy lesson

This column is a periodic series of personal reflections on journalism, news literacy, education and related topics by NLP’s founder and CEO, Alan C. Miller. Columns are posted at 10 a.m. ET every other Thursday.

The PBS NewsHour segment on the News Literacy Project had just aired.

“How was it?” my colleague asked me.

“Great for us,” I responded. “But I think PBS is going to have a problem with Fox.”

Little did I know that what was about to unfold would be a high-profile news literacy lesson itself.

On Dec. 13, 2011, the NewsHour aired a nearly seven-minute report on NLP, by senior correspondent Jeffrey Brown, that included an interview with me.

In one of the soundbites, I said that “in this hyperlinked information age … there is so much potential here for misinformation, for propaganda, for spin, all of the myriad sources of information out there.”

As I uttered the words “myriad sources of information out there,” a two-second visual illustration (“cover,” in broadcast parlance) appeared on screen — a screenshot of Bill O’Reilly of Fox News, an outspoken conservative and the host of The O’Reilly Factor, the most popular cable news program in the country. The NewsHour producers could easily have juxtaposed O’Reilly’s picture with a balancing shot of a left-leaning MSNBC host — but, for whatever reason, they didn’t.

Sure enough, my phone rang the next day. It was Juliet Huddy, a Fox News correspondent. She said O’Reilly was furious that PBS had attacked him, and she wanted me to comment.

After consulting NLP board members, I declined and suggested that Huddy seek comment from PBS, since its program had produced the piece. I also declined to respond to a far more insistent message left on my voicemail later that afternoon.

That evening, throughout his hour-long show, O’Reilly urged viewers to stay tuned to see how PBS had “attacked” The O’Reilly Factor.

His piece opened with my soundbite. O’Reilly responded in high dudgeon.

“Are you kidding me? Are you kidding me?” he said. “PBS showing my picture when talking about propaganda and misinformation? Good grief. Where can I sue?”

He then brought on Huddy. She described NLP and said it has “a great message.” She added that I had told her, “Look, I wasn’t involved in the editing,” and had referred her to PBS. She said she also spoke to the NewsHour producers.

“They didn’t apologize, right?” O’Reilly said, referring to me, the NewsHour producers and PBS. “OK, so now I’m going to hunt them down.”

Then he singled me out with a favorite pejorative, a term he reserved for “those who are doing awful, dumb, or evil things.”

“I don’t believe this pinhead for a moment who says he didn’t see the product before it went on,” he said as my photo was displayed on the screen. “Everything that goes on a national — you watch it before it goes on. All right? If your name is attached, you watch it.”

In fact, as O’Reilly surely knew, the subjects of television news reports do not usually see the piece in advance and, as Huddy sought to convey on my behalf (albeit unsuccessfully), I hadn’t, either.

I quickly discovered which friends and family members were fans of The O’Reilly Factor.

As soon as the show ended, my phone rang. It was a long-time friend. His first words: “Alan, you pinhead!”

Then my mother called. Her brother, my Uncle Melvin, had called her to ask if I was in trouble. “Bill O’Reilly is mad at Alan,” he told her.

I thought I might also hear from Huddy. Instead, two days later, I got a call from Michael Getler, the ombudsman (public editor) for PBS.

He asked if I had seen the NewsHour segment before it aired. When I said I hadn’t, he told me that he was writing a piece criticizing the program for its handling of O’Reilly’s photo and that the NewsHour was going to apologize to O’Reilly.

In the item that Getler posted that afternoon, he quoted Anne Bell, a NewsHour spokeswoman, saying that the segment about NLP included “several examples of a wide range of news outlets,” including Fox News, MSNBC and the BBC. “At no point,” Bell told Getler, “does the NewsHour pass judgment on the quality of any outlet shown.”

But, Getler wrote, “unless you were a cryptographer with laser vision, the only recognizable image was that of O’Reilly.”

“Miller, who had nothing to do with the editing or what was chosen to illustrate it, and Brown are both excellent and highly respected journalists,” Getler added. “But the picture of O’Reilly used by segment producers distracted from the otherwise excellent content.”

Ultimately, Getler wrote, he was told since O’Reilly was “the only visibly recognizable newsperson in the sequence,’’ the NewsHour apologized for the “unintended implication” that O’Reilly engages in “spin.”

Imagine.

This saga offers two compelling news literacy lessons. The first: Journalists must always be mindful and fair with even something as seemingly minor as a two-second visual. The second: PBS’s appointment of an ombudsman with the independence to criticize its programming (and prompt an apology) affirms its accountability to its editorial standards and practices.

On his Dec. 19 show, O’Reilly gleefully announced that PBS had apologized to him. “We accept PBS’s apology,” he said.

I am still waiting for mine from him.

Read more from this series:

- Apr. 22: Spotlight — a special resonance

- Apr. 8: The 19th* — a nonprofit news startup made for the moment

- Mar. 11: Fighting the good fight to ensure that facts cannot be ignored

- Feb. 26: Students’ enduring rights to freedoms of speech and the press

- Feb. 11: We need news literacy education to bolster democracy

- Jan 28: 13 lessons from our first 13 years

- Jan. 14: Media needs to get COVID-19 vaccine story right

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Dec. 3: Combating America’s alternative realities before it’s too late

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 29: High stakes for calling the election

- Oct. 15: In praise of investigative reporting

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news

Behind the headlines: Atlanta shootings coverage fallout

By Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington

This article is from this week’s issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

News coverage of the March 16 fatal shootings at Atlanta-area spas that occurred amid a recent spate of anti-Asian violence across the country spurred important debates over journalism ethics and news decisions — especially as the story first unfolded. Questions and criticisms of coverage highlighted several notable issues, including the bias and credibility of law enforcement sources; the need for more diverse news organizations, journalists and sources; and hesitation by newsrooms to call the shootings a “hate crime.”

Protestors hold signs at the End The Violence Towards Asians rally in Washington Square Park on Feb. 20, 2021 in New York City. Credit: Ron Adar / Shutterstock.

Protestors hold signs at the End The Violence Towards Asians rally in Washington Square Park on Feb. 20, 2021 in New York City. Credit: Ron Adar / Shutterstock.

As the story developed, the Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) published guidance for newsrooms covering the shootings. Its recommendations include providing context on the recent increasing violence, and understanding the history of anti-Asian racism. It also underscored the need to consult Asian American and Pacific Islander expert sources and to be careful with language that could contribute to “the hypersexualization of Asian women.”

AAJA reported that some newsrooms have questioned whether Asian American and Pacific Islander journalists will show bias or are “too emotionally invested” to cover the shootings. Calling such reports “deeply concerning,” it urged news organizations to empower these journalists “by recognizing both the unique value they bring to the coverage of the Atlanta shootings and the invisible labor they regularly take on, especially in newsrooms where they are severely underrepresented.”

Note: AAJA also released a pronunciation guide for Asian victims of the shootings.

Related:

- “The rush to report on Atlanta-area shootings amplified bias in news coverage” (Doris Truong, Poynter).

- “Connie Chung: The media is miserably late covering anti-Asian violence” (Alexis Benveniste, CNN Business).

- “‘Enough Is Enough’: Atlanta-Area Spa Shootings Spur Debate Over Hate Crime Label” (Bill Chappell, Dustin Jones, NPR).

- “Why don’t we know more about the Atlanta shooting victims?” (Ariana Eunjung Cha, Derek Hawkins and Meryl Kornfield, The Washington Post).

- “Teen Vogue’s New Top Editor Out After Backlash Over Old Racist Tweets” (Maxwell Tani, Lachlan Cartwright, The Daily Beast).

Ms. publishes commentary on pioneering women journalists

NLP’s Ebonee Rice shares the stories of pioneering women journalists and how their work helped make the careers of current women journalists possible. She wrote the piece in honor of Women’s History Month.

“For many years, women played less visible roles in national and international media, doing their jobs while fighting for their seats at the leadership table,” Rice writes in the March 16 Ms. magazine piece, A Tribute to Women in Journalism Who Cracked Glass Ceilings.

“But this month reminds us that we need to do more to ensure young women aren’t excluded and that they have the opportunities to help create a better-informed and more news-literate world,” Rice concludes

Black History Month: Pioneering journalists, media

This February, during Black History Month, we’re shining a light on pioneering Black journalists and news media from the past two centuries. Many of these reporters and outlets overcame incredible obstacles and discriminatory systemic structures to report the facts in their communities. Many are also relatively unknown to the news-consuming public. We hope to help change that. Follow our Twitter thread throughout February as we highlight a journalist and/or news outlet each weekday.

We began by highlighting the Freedom’s Journal, the first Black-owned and -operated newspaper in the United States. The four-page, four-column paper debuted in 1827, the same year that slavery was abolished in New York State. Like many of the publications operated by or created for Black Americans that would follow, Freedom’s Journal served to counter racist commentary published in the mainstream press.

Twenty years later, Frederick Douglass and Martin Delaney launched The North Star. The abolitionist newspaper would become the most influential anti-slavery publication of the 19th century, focusing on anti-slavery progress, women’s rights and Black empowerment. The North Star published 565 issues between 1847 and 1851, according to the Library of Congress. In the late 1800s, Black investigative journalism rose to the forefront as Ida B. Wells exposed the widespread practice of lynching, particularly of Black men. Wells’ work is featured in our Checkology® lesson “Democracy’s Watchdog.”

Still publishing today

The 1900s saw the creation of more Black-owned newspapers, including two of the most respected publications that still publish today. Robert Sengstacke Abbott founded The Chicago Defender in 1905, and shepherded its growth into a local paper with a weekly circulation of 16,000 in its first decade. James H. Anderson put out the first edition of the Amsterdam News, a New York paper, on Dec. 4, 1909, with six sheets of paper and a $10 investment. The publication grew quickly to cover not just local stories but national news as well. A year later, in 1910, W.E.B. Du Bois served as the editor of the NAACP’s first issue of The Crisis, its official magazine. It took off from there.

Continuing chronologically through the 1900s, we’re highlighting just some of the many Black journalists that made indelible impacts with their reporting. From Charlotta A. Bass to Ted Poston and on and on, follow our Twitter thread for more throughout February.

NewsLit Week | Michigan students committed to fact-based journalism

Michigan students tell FOX 17 how they are committed to fact-checking and getting the whole story in the segment Rockford High School students showcase news literacy skills, which aired on Jan. 25. The students produce their own broadcast program Beyond the Rock.

Upon Reflection: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ also reflects its accountability

Note: This column is a periodic series of personal reflections on journalism, news literacy, education and related topics by NLP’s founder and CEO, Alan C. Miller.

On Sept. 28, 1980, during the height of the drug epidemic in the nation’s capital, The Washington Post published a heart-rending profile of “Jimmy,” an 8-year-old heroin addict. It caused a national sensation.

Police and social workers launched a massive search for the boy, whose identity the paper refused to disclose. The following April, the reporter, Janet Cooke, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, journalism’s highest honor, for feature writing.

But her story was a lie. The boy was never found, and Cooke ultimately acknowledged that she had invented him. The Pulitzer committee withdrew the award — for the first time in the history of the prizes — and the Post published a voluminous report on its failure to catch the fabrication. Cooke resigned; her promising journalism career abruptly ended.

In the four subsequent decades, there have been other high-profile cases where journalists working for reputable news organizations made things up. They include fabulists whose names are synonymous with the cardinal sin of their craft — Stephen Glass (PDF) of The New Republic, Jayson Blair of The New York Times and Jack Kelley of USA Today. More recently, NBC News’ Brian Williams was found to have embellished accounts of his derring-do as a reporter.

The consequences of these self-inflicted wounds were enormous — not just for the perpetrators, but also for their news organizations. But the greatest damage was to the public’s trust in journalism. Cooke’s case, less than a decade after the Post’s triumphant Watergate reporting, first weakened that bond. The transgressions of Glass, Blair, Kelley and Williams further eroded it.

Nonetheless, as counterintuitive as it might sound, these iconic cases can, in fact, be viewed as a reason to trust journalism.

For one thing, there have been relatively few such scandals in the four decades since “Jimmy’s World” was published. For another, the news organizations took responsibility, acknowledged the damage, and published exhaustive investigations into how these lapses happened. Some of these breaches led to systemic institutional changes. And Cooke, Glass, Blair and Kelley have not worked in journalism again (we’ll return to Williams below).

Before and during his time as president, Donald Trump has insisted that critical news coverage is “fake news” and accused those who cover him of making things up, even as he has misled the public on a variety of topics — from silly ones (the size of the crowd at his inauguration) to matters with implications for public health (the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic) and for democracy itself (the outcome of last month’s presidential election).

Yes, there have been rare ethical lapses; I note a few below. But in contrast to the many purposely deceptive websites and some viral user-generated content on social media platforms — produced with no rigor, standards, accountability or transparency — quality journalists and news outlets do not make things up. Period.

To be sure, journalism is imperfect by its nature. Journalists make mistakes for a variety of reasons: the rush of deadlines, competitive pressure, sources who mislead or outright lie, honest errors. The truth often takes time to emerge. There is a reason that journalism is called “the first rough draft of history.”

Beyond the fabulists, there have been other high-profile, and even more damaging, cases, where news organizations retracted major stories that involved serious lapses in the vetting of sources and documents or deeply flawed reporting and editing. Glaring examples include CNN’s 1998 report on Operation Tailwind, charging that the U.S. military had used sarin, a deadly nerve gas, against American defectors during the Vietnam War, and a 2014 piece in Rolling Stone detailing an alleged rape at the University of Virginia.

In 2004, The New York Times produced a post-mortem of its Iraq reporting that was highly critical of its own credulous accounts of the existence of weapons of mass destruction — weapons that failed to materialize in Iraq and helped lead the U.S. into a prolonged and costly war. That same year, CBS News acknowledged that it was “a mistake” to have based a report about George W. Bush’s service in the Texas Air National Guard on memos that it could not prove were authentic.

But here, too, internal inquiries followed, and careers — including those of prominent correspondents and senior news executives — were dashed or diminished.

In addition, many news organizations, including digital-only outlets like Vox and Axios, routinely publish corrections of factual errors, down to the misspelling of a name or an erroneous date. Some have ombudsman or a readers’ representative who responds to issues of accuracy and ethics. Many journalism organizations also have ethics codes (here, for example, is the Society of Professional Journalists’). This reflects the fact that reputable news organizations have standards; when those standards are violated, corrections and consequences follow — or at least they should.

You might ask yourself this question about any source of information that you trust: When was the last time it issued a correction?

I know something about this subject after 29 years as a newspaper reporter, most of them spent in the Washington bureau of the Los Angeles Times. I participated in the meticulous reporting, editing and vetting process that my colleagues and I brought to our work. This included high-stakes investigations involving the political campaigns and administrations of Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, the U.S. Marine Corps and U-Haul. I sweated every word and every fact right up until the presses ran. My handful of corrections, most of them minor, sting to this day.

Admittedly, not all journalism transgressions — and transgressors — are created or treated equally.

Brian Williams shared false accounts of his reporting — both on the air and in interviews on late-night talk shows — when he was one of the most trusted names in journalism as the anchor of the NBC Nightly News. When these fabrications were disclosed in 2015, he was suspended for six months without pay. He returned to the air in September 2015 as a breaking news anchor on MSNBC; a year later, he was named the host of a newly created late-night news wrap-up on the cable network, The 11th Hour with Brian Williams — a position he still holds.

Janet Cooke, the first Black woman to win a Pulitzer (before she lost it), is about to make a comeback of sorts as well: A Netflix film based on her story is in the works.

Jayson Blair, whose serial deceptions at The New York Times exposed shortcomings in internal safeguards at the paper and helped lead to the resignation of its two top editors in 2003, has had no such revival. “I still love journalism. I miss it,” he told students at Duke University in 2016. But, he added, “it just doesn’t work without the trust.”

Read more in this series:

Upon Reflection: In praise of investigative reporting

Note: This is the second in a periodic series of personal reflections on journalism, news literacy, education and related topics by NLP’s founder and CEO Alan C. Miller.

As news reports go, The New York Times’ lead story on Sept. 27 was a blockbuster: Donald Trump paid only $750 in federal income tax the year he won the presidency, $750 in federal income tax his first year in office, and “no income taxes at all in 10 of the previous 15 years — largely because he reported losing much more money than he made.”

I admired the way that Russ Buettner, Susanne Craig and Mike McIntire were able to make these assertions. The Times didn’t even feel the need to provide any attribution for those stunning findings in the story’s opening paragraphs.

That’s because this reporting was based on a trove of tax-return data for Trump and his companies that extended over more than two decades, as well as on other financial documents, legal filings and dozens of interviews. The three reporters, who collectively have decades of experience in unraveling complex financial and political dealings, have been investigating Trump’s finances for nearly four years.

Their efforts culminated in a classic piece of investigative journalism. It broke significant new ground on a subject of enormous public interest with authoritative, compelling and contextual reporting. It did not ask for the reader’s trust; instead, it earned it with detailed documentation. It pulled no punches in sharing its evidence-based findings — while also explaining what remains unknown about Trump’s assets.

The response was telling. A lawyer for the Trump Organization told the Times that the story was “inaccurate” but did not cite specifics. Trump called the report “fake news,” again without citing specific errors. In investigative journalism circles, this is called “a non-denial denial.”

I have a special appreciation for what it takes to do this kind of work. For most of my 29-year newspaper career, I was an investigative reporter. I considered it journalism’s highest calling. In some ways, even as newspapers fold and the number of journalists drops in the face of economic contraction, we are in a new golden age of investigative reporting. Yet amid all the attacks on journalism and the public’s declining trust in it, I believe that most people do not truly understand what it takes to do this work well — and the stakes and standards that lie at the heart of it.

In theory, all reporters should have the ability to do investigative work. Indeed, some of the most iconic investigations have arisen from resourceful beat reporting. But those who devote themselves exclusively to this kind of work — for instance, the members of Investigative Reporters & Editors — are often a different breed who march to a different beat.

They focus principally on corruption, waste, fraud, dishonesty and abuse, whether of human rights or of public trust. They tend to take longer and dig deeper, obtaining records (often through federal or state freedom of information requests), developing a network of inside and expert sources, and thoroughly mastering the subject at hand. Their work typically must endure a multi-layer editing process, often including a review by their publication’s lawyers.

Investigative reporters tend to regard whoever wields power as their primary target. Their north star is impact — to make a difference.

To succeed, their work must be beyond reproach. Most investigations contain hundreds of facts on which findings are based. The subject of such a report will look for any factual error, however inconsequential, to try to undermine the story’s credibility (“If they can’t get even that right, why would you trust their conclusions?”). The threat of a lawsuit, even prior to publication, may hang overhead as well.

In December 2002, following months of reporting, the Los Angeles Times published “The Vertical Vision,” a four-part series on the Marine Corps’ aviation program. My colleague Kevin Sack and I detailed how the Harrier jump jet, the first aircraft the Marines could call their own, had killed 45 pilots — including some of the Corps’ best — in 143 noncombat accidents since 1971, making it the most dangerous aircraft in the U.S. military for decades. We demonstrated that this was the first of three Marine aircraft that would prove to be deeply troubled, painting a portrait of an aviation program whose high cost in blood and treasure was not redeemed on the battlefield.

In our determination to be both fair and accurate, we took the unusual step of reading, word by word, a draft of the series to Marine Corps public affairs officials. In turn, as publication began, the Marines sent supporters a detailed description of what to expect and told them that if they could find any mistakes, however small, the Corps would pounce on those errors to discredit the entire report. (They found nothing. The series led to a congressional hearing and was awarded the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting.)

Investigative reporters must resist a particular kind of confirmation bias: falling in love with the story, or with the thesis behind an investigation. The best reporters follow where the evidence leads, rather than seeking documentation to support a desired conclusion. Failing to do so has consequences, as I discovered in my first journalism job at the Times Union in Albany, New York.

I made a critical mistake on an investigative piece about the city’s Democratic machine when I saw and reported what I expected — and, yes, hoped — to see in a legal document. “Always guard against your own assumptions,” my editor, Harry Rosenfeld, admonished me. (His words held special sway since he had been Bob Woodward’s and Carl Bernstein’s boss at The Washington Post during the Watergate investigation.) That — plus the ensuing Page One correction — proved a powerful lesson for an ambitious young reporter.

(This fealty to accuracy, as well as to accountability in the face of factual errors, stands in stark contrast to other types of content that masquerade as journalism — such as conspiracy theories, whose web of alleged insider information, sinister plots and Byzantine clues can take on the aura of reportorial revelation. But these delusions, which require their followers to suspend belief in reality, fall apart under scrutiny because they cannot be independently documented by credible sources.)

The high expectations placed on investigative reporters also put them under considerable pressure. Producing a series — or even a single story — can take weeks or months, and that time is costly (especially amid tightening budgets). Sources can mislead. Tips don’t always pan out. And a newly discovered fact or document may undo those weeks or months of work by disproving or complicating an investigation’s underlying premise.

Yet overcoming such challenges makes the payoff all the more gratifying: landing an investigation that reveals wrongdoing, prompts public scrutiny, leads to reforms and has meaningful impact.

In early 2003, two months after our Harrier series appeared, a Marine Corps pilot stationed in Kuwait said this to a Los Angeles Times colleague: “Tell Alan Miller that he got it right.” As a result, he added, “Lives will be saved.”

Read more in this series:

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Dec. 3: Combating America’s alternative realities before it’s too late

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 29: High stakes for calling the election

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news