Science teacher couldn’t have planned it any better

His course was ready to meet new media literacy requirement

Illinois high school educator Tom Foss credits his experience with both skeptics and conspiracy theorists and a background in science and humanities for preparing him to teach media literacy.

“I used to be active in scientific skepticism circles. I did presentations on chain letters, scams and conspiracy theories. That was my window in, and I think a lot of critical thinking is just scientific thinking,” said Foss, who teaches chemistry, physical science and physics to grades 9-12 at Newark Community High School in rural Illinois.

Having majored in physics and English in college, he brings these dual perspectives to the classroom. Nearly a decade ago, he began assigning research projects to his chemistry students and included a lesson on how to find reliable scientific sources. Then the pandemic hit, suspending in-person classes. “I needed something to teach on our remote days,” Foss said.

He found the Stanford History Education Group’s Civic Online Reasoning resources and other material for teaching students how to determine the credibility of sources and information. By the end of the 2020-21 school year, he had built a curriculum that brought a science lens to media and news literacy, but he had no place to fit it into his courses.

“I saw much more retention and deeper thinking and more tangible results by doing this as an extended process. This made it really clear we needed more than one unit,” he said.

Mandating media literacy

Foss spoke with teachers who recognized the value of his approach and then learned that Illinois was about to pass a law requiring media literacy instruction beginning in the 2022-23 school year. Foss called it serendipity, but at his school his work was more like the catalyst for a news literacy chemical reaction — a process that generates products which then sustain that process.

With a curriculum in hand, media literacy became a semester-long required class for freshmen at his school in fall 2022. When researching resources for the new class, Foss discovered the News Literacy Project and its Checkology® virtual classroom, which helped him bring a comprehensive approach and common vocabulary to the course. Among the Checkology lessons he teaches are “InfoZones,” “Misinformation,” Understanding Bias” and “Making Sense of Data.”

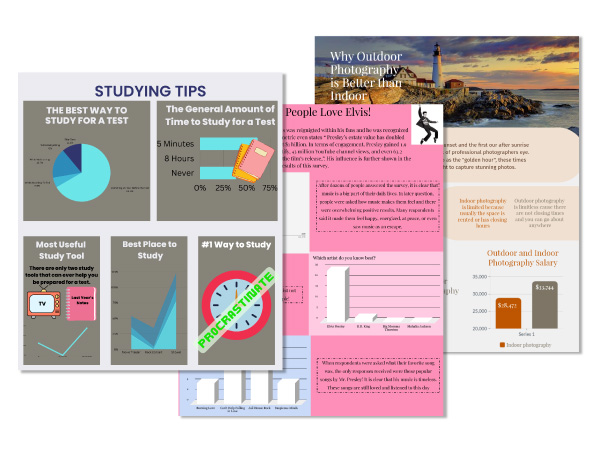

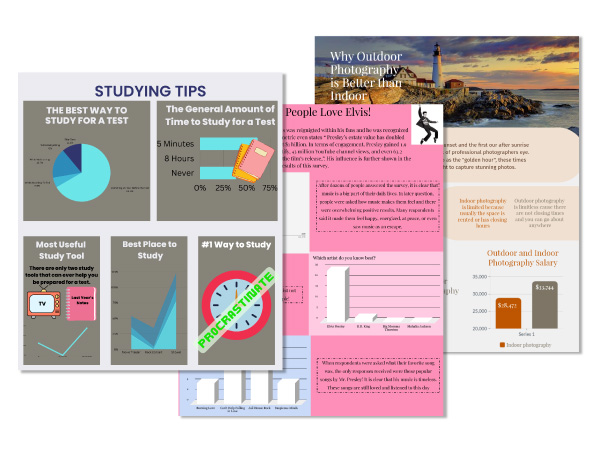

Work done by students in Foss’ class.

Foss wants his students to understand that things often are more complicated than they seem, with a greater level of complexity underneath. “The simple narratives are almost always obfuscation. You should always question simple things that feel right,” he tells his students. He wants them to have the skills to analyze information, find credible sources and be open to changing their minds when confronted with evidence that contradicts their beliefs. “That’s a really hard thing for anyone to do.”

The course has opened students’ eyes to the darker elements of the internet. They are surprised to discover how easily their privacy can be violated, how little control they ultimately have over what they post and how seamlessly legitimate content can be turned into misinformation.

“They’ll notice a deepfake edit but they’ll miss the caption that gives it false context. I tell them the easiest way to fool you doesn’t require Photoshop or After Effects, it can take only a few words,” he said. “I’m really proud when I start seeing the kids make distinctions between what they’re being told and what they’re seeing.”

Artificial intelligence a new challenge

This skill is particularly important given the ways artificial intelligence is making it increasingly difficult to tell what’s real and what’s not. And that goes for educators, too, as students have always found hidden ways to get others to help with assignments. Up to now such interference has been decidedly analog. “It’s more that kids have their friends do their homework. The original AI.” Foss quipped.

Before the 2022-23 school year even ended, he was thinking about ways to improve his curriculum for the fall. He’ll create a “bell ringer” activity to start each class; he’ll tweak the lesson sequence; pare down some sections and beef up others, and give students a more active role. “I want them to do more hands-on work rather than listening to me talk,” he said.

And Foss can’t wait to see what lasting impacts media and news literacy competency has on his students. “I’m really interested to see this group of freshmen four years from now when they do their senior capstone [research] projects.”