The Sift: AI chatbots harming teens | Embracing influencers

| Hi there, This is the last issue of The Sift in 2024! This newsletter is taking a winter break and will return in the new year on Jan. 13. In the meantime, if you find The Sift helpful in your teaching, please consider sharing this newsletter with your colleagues by forwarding this email. Have a wonderful holiday! — The Sift team |

In this issue

AI chatbots harming teens | Embracing influencers | RumorGuard slides | Daily Do Now slides

Daily Do Now slidesDon't miss this week's classroom-ready resource.  |

Top picks

Educators, here are the latest news literacy topics and tips on how to integrate them into your classroom.

| Parents are suing an AI chatbot app for messaging teens and kids about violence, self-harm and sexual content. |

1. When algorithms and AI chatbots cause harm to teens

When Anna Mockel was 14, she aimlessly watched whatever videos YouTube recommended — until her feed was awash in ultra-skinny girls and weight-loss videos. Mockel became fixated on losing weight and was eventually hospitalized with anorexia, she told CBS News. Now 18, Anna said YouTube — the most popular platform for teens — became, for her, a “community of people who are competitive with eating disorders.” She’s far from the only one. A new Center for Countering Digital Hate report found that when YouTube users show signs of being interested in weight loss, nearly 70% of recommended videos include content that may provoke anxiety about body image.

Artificial intelligence chatbots are also resulting in harm to children and teens. A Texas mom said that an AI chatbot app, Character.ai, encouraged her 17-year-old son to cope with sadness through self-harm and suggested he kill his parents [link warning: violent references and self-harm]. The mom recently filed a lawsuit against Character.ai, and she is joined by another parent who said her 11-year-old daughter was exposed to sexual content on the app. In October, Character.ai was also sued by the mother of a teen who died by suicide after chatting with the app.

Following the lawsuits, Character.ai announced that it is adding new safety features for teens, including parent controls, prominent disclaimers that chatbot characters aren’t real people and a pop-up to a suicide prevention hotline when expressions of self-harm are detected.

| Discuss: |

Do algorithms reflect our interests or shape them? Or both? How can algorithms designed to engage people based on their pre-existing ideas and interests cause harm? Do you think most parents are aware that some teens “chat” with AI tools to seek companionship and advice? What can you do to make your peers aware of the hazards of chatbots like Character.ai?

| Idea: |

Use the “Reflect” slide in Week 11 of Daily Do Now to further explore this topic.

| Related: |

- [Link warning: self-harm] “Google-Backed AI Startup Tested Dangerous Chatbots on Children, Lawsuit Alleges” (Futurism).

- [Link warning: self-harm] “Can A.I. Be Blamed for a Teen’s Suicide?” (The New York Times).

- “Violence on social media making teenagers afraid to go out” (The Guardian).

★ NLP Resources:

“Introduction to Algorithms” (Checkology® virtual classroom).

Infographic: “6 things to know about AI”

2. Will journalists start to embrace influencers as allies in 2025?

More Americans are turning to influencers for news. That’s one reason why Marlon A. Walker, managing editor for The Marshall Project, predicts that in 2025 journalists will embrace influencers as allies in amplifying their work and making “complex topics feel accessible and engaging.”

His look ahead is one of 90 year-end predictions of how the field of journalism will change in 2025, published by Nieman Lab. Other notable predictions: norms for conflicts of interests may shift, the rebirth of local news through nonprofit outlets, community demand of local news reporters (who may increase their standing as news influencers), delays to FOIA requests and less pessimism from young journalists.

| Discuss: |

What’s the difference between a journalist and an influencer? Do journalists and influencers have the same editorial standards and ethical guidelines? What similarities do the two groups share? Do you think it’s a good idea for journalists to embrace influencers as allies? Why or why not?

| Idea: |

Share two social media videos with students — one from a journalist or news organization and one from a news influencer. Ask students to compare and discuss the questions below. (For examples of short-form journalist videos, you can try The Washington Post TikTok page or The Wall Street Journal YouTube Shorts page. For examples of popular influencers, Dylan Page discusses news topics on TikTok and Instagram, and Khaby Lame on TikTok has humor videos.)

| Note: |

For tips on teaching what credibility looks like on TikTok, check out “Teach With TikTok: Help Students Stick to the Facts on Social Media,” an edWeb webinar presented by NLP staff.

| Related: |

- “‘News influencers’ are racking up billions of views — and not checking their facts” (The Conversation).

- Video: “Opinion: How Being an Influencer Became a New American Dream” (The New York Times).

★ NLP Resources:

Infographic: “Seven standards of quality journalism”

Poster: “Six zones of information.”

“InfoZones” (Checkology virtual classroom).

3. Journalism: ‘Hear something. Check something.’

Journalists sometimes spend hours working on stories that never get published. This happened recently when ProPublica, a nonprofit investigative news site, stumbled onto a potentially newsworthy scoop: that President-elect Donald Trump’s nominee for secretary of defense, Pete Hegseth, may not have been admitted into West Point — even though Hegseth said he had been.

ProPublica — as part of doing its due diligence — inquired with the U.S. Military Academy to confirm Hegseth’s story. A West Point spokesperson told ProPublica that Hegseth had never applied. Reporters called back to confirm: Did this mean Hegseth was never admitted? Yes, another spokesperson confirmed. As any serious standards-based news organization would, ProPublica contacted Hegseth’s staff to give him a fair chance to respond. They refuted the allegations, and ProPublica continued to dig.

Ultimately, the potential story was false and ProPublica never published it. West Point admitted to an “administrative error.”

ProPublica editor and reporter Jesse Eisinger wrote on Bluesky, “This is how journalism is supposed to work. Hear something. Check something. Repeat steps 1 and 2 as many times as needed.”

| Idea: |

Dig into the work of fact-checkers by sharing this 14-minute NLP News Goggles video featuring Karena Phan of The Associated Press with your students. Then use this viewing guide for students to take notes on how journalists fact-check stories. (This guide also includes teaching notes!)

- Another idea: Connect with a journalist to schedule a visit with your students virtually or in-person through NLP’s Newsroom to Classroom program. Ask them to share examples with your students about the lengths to which they go to verify and double-check even the most minor of facts — and if they’ve ever discovered that an apparent scoop was erroneous.

| Related: |

- Video: “‘Unethical garbage’: ProPublica faces backlash for ‘journalism’ claim after email to Hegseth gets exposed” (Fox News).

★ NLP Resources:

“Practicing Quality Journalism” (Checkology virtual classroom).

“What Is News?” (Checkology virtual classroom).

Lesson plan: “News judges”

★ Featured classroom resource:

|

No, world leaders didn’t sign ‘Age of Death’ treaty

❌ NO: World leaders did not sign a World Economic Forum treaty to introduce “age of death” laws requiring people to seek government approval to live past a certain age in the Western Hemisphere.

✅ YES: This story originated with The People’s Voice, a website with a long history of publishing hoaxes.

❌ NO: The WEF website does not contain any mention of “age of death” laws.

❌ NO: The WEF, an international nonprofit that encourages cooperation among global leaders, does not make policy.

★ NewsLit takeaway

Supposed screenshots of news articles should always be viewed with skepticism as they often turn out to be impostor content or, in this case, trace back to a disreputable website. Here are some things to consider when encountering similar claims online:

- Check the source. Trace a screenshot of a news article back to its source by doing a web search for the headline or title.

- Consider credibility. Search for the site’s name and see if any recognizable and credible news outlet has reported on it.

- Get a second source. Legitimate news stories are covered by multiple credible news outlets. If you can’t find other stories, it’s a red flag.

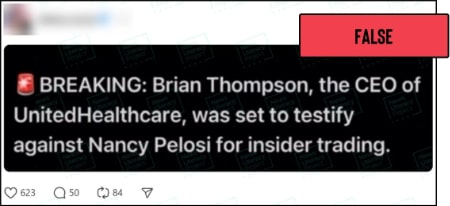

False conspiracy links health care CEO death and Pelosi

❌ NO: Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is not under investigation for insider trading.

✅ YES: UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson was on his way to an annual investors meeting in New York City on Dec. 4 when he was killed.

❌ NO: He was not about to testify against Pelosi.

✅ YES: Thompson was named in a lawsuit this year alleging fraud and insider trading.

★ NewsLit takeaway

A common conspiratorial trope involves the idea that whistleblowers, or people with damaging information against celebrities or government officials, are killed to prevent that information from becoming public. While this idea may be intriguing — and is the plotline of many suspense movies — these claims are largely built on shoddy evidence and faulty connections. Here are a few tips to catch these conspiratorial claims before they spread:

- Look out for the misuse of journalistic terms, such as “breaking” news, which are often used to make fabricated claims seem credible.

- Check for evidence. A social media post containing a sensational claim without any supporting evidence should be viewed with skepticism.

When reading about trending topics, especially ones that elicit strong emotions, it is important to exercise caution, since conspiracy theorists and other purveyors of disinformation frequently use these subjects to spread false claims.

| Need to reset your algorithm? A communications studies professor shares how to do this in this CBS News video. One tip: Mute buttons and privacy settings are helpful, depending on the platform. | |

| Since the Israel-Hamas war started in October 2023, 137 journalists and media workers have been killed, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Most of the journalists killed —129 — were Palestinian. | |

| This year 48 journalists were arrested or detained by police in the United States — more than the previous two years combined. Most of the arrests (90%) occurred around anti-war protests. | |

| Imagine getting a push notification with a headline about a sensational and shocking thing that … never happened. This was a reality recently when Apple Intelligence ran a false AI-generated headline about the Luigi Mangione case and attributed it to BBC News. | |

| Shady and deceptive “nudify” websites use generative AI technology to make fake nude images of real people — causing real life harm, especially to teenage girls in high school. | |

| Ever read the replies under a social media post? A new report found that politicians and online influencers have a significant impact on the spread of climate misinformation online — including through replies their posts elicit. | |

| Can you guess the most popular social media platform among teens? It’s ::drumroll:: YouTube (followed by TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat). That’s according to a new Pew Research Center survey that also found that a third of teens “use at least one of these sites almost constantly.” | |

| TikTok has until Jan. 19 to change ownership or be kicked out of the U.S. While a federal court upheld that a TikTok ban doesn’t violate the Constitution, online speech advocates say it would set a dangerous precedent. | |

| When talking with loved ones about the scientific consensus on vaccinations and other health decisions, one expert recommends actively listening with empathy and respect before sharing evidence. |

Thanks for reading!

Your weekly issue of The Sift is created by Susan Minichiello (@susanmini.bsky.social), Dan Evon (@danieljevon), Peter Adams (@peteradams.bsky.social), Hannah Covington (@hannahcov.bsky.social) and Pamela Brunskill (@PamelaBrunskill). It is edited by Mary Kane (@mk6325.bsky.social) and Lourdes Venard (@lourdesvenard.bsky.social).

You’ll find teachable moments from our previous issues in the archives. Send your suggestions and success stories to [email protected].