The Sift: TikTok’s Footnotes | Fake missing child scam

|

Hi Sift reader, We need your help! Please tell us about your experience using The Sift in our annual reader survey. We aim to make this newsletter as useful as possible for your teaching, and we appreciate hearing your feedback. At the end of the survey, you can also enter a drawing to win one of four $50 Amazon gift cards.😊 Thank you! — The Sift team |

In this issue

TikTok's Footnotes | Fake missing child scam | RumorGuard slides | Daily Do Now slides

Daily Do Now slidesDon't miss this classroom-ready resource.  |

Top picks

Here are the latest news literacy topics and tips on how to integrate them into your classroom.

| A backlog of public records requests at health agencies is expected to worsen. |

1. Will mass layoffs threaten public records release?

Journalists rely on public records for information, but recent mass layoffs at government agencies mean fewer workers to fulfill records requests. Through the Freedom of Information Act, anyone can file a public records request and obtain government data, reports, meeting notes, photos, emails and more — and it’s an essential tool in journalism. But FOIA staff at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services were among 20,000 workers recently dismissed.

FOIA requests help hold government accountable. For example, at federal health agencies public record requests helped push companies into taking unsafe drugs off the market. The department says it will continue processing FOIA requests, but it’s unclear how effective it will be with fewer staff and an ongoing backlog, according to health services researcher Reshma Ramachandran.

| Idea: |

Share this NLP TikTok video (also on Instagram) with students to learn about how Michigan State University student journalists have used public records requests in their reporting.

- Another idea: Use the “Watchdog role” slide from Week 21 in the Daily Do Now resource to further explore this topic.

| Discuss: |

How do FOIA requests help investigative journalists in their watchdog role? In what ways can public records requests bring about social or political change? Why might government agencies redact — or withhold or black out — information on public records?

| Related: |

- Commentary: “In the US, information gets less free” (Reuters).

- “Firings at Federal Health Agencies Decimate Offices That Release Public Records” (KFF Health News).

2. Should algorithms decide what’s popular?

Whether it’s the movies you watch or the clothes you buy, algorithms steer social media users to popular content — and what’s already popular becomes more popular. But some people are pushing back against what journalist and author Kyle Chayka calls “peak algorithm” to build relationships and develop cultural taste outside of machine curation. Because algorithms push users to content that’s similar to what they already like, it can also be challenging to find new content.

Algorithms didn’t always drive social media and streaming content. In the early days of YouTube, a team of “coolhunters” would search for interesting — but not necessarily popular — videos to feature on the site’s homepage. YouTube later shifted to featuring algorithm-driven content.

| Discuss: |

How do algorithms shape your interests? Why do search engines and social media platforms use algorithms? What’s lost when social media users only consume algorithm-recommended content?

| Idea: |

Use the “Analyze” slide from Week 21 of the Daily Do Now resource to further explore the impact of social media algorithms.

★ NLP Resource:

“Introduction to Algorithms” (Checkology® virtual classroom)

| Related: |

- “A Long-Shot Bet to Bypass the Middlemen of Social Media” (The New York Times).

- Opinion: “The outrage algorithm: Social media benefits from division” (The Daily Texan, The University of Texas at Austin student newspaper).

3. TikTok debuts fact-checking Footnotes

TikTok recently began experimenting with crowdsourced fact-checking through its new Footnotes feature. The video-sharing app joins X and Meta as the latest company to invite users to add more context to content on the platform. TikTok will still work with more than 20 fact-checkers on its platform, unlike Facebook owner Meta, which recently ended many of its fact-checking partnerships. Poynter analyses found that crowdsourcing can be effective as “part of a holistic fact-checking approach” — but falls short when used as a standalone solution to curbing misinformation.

| Discuss: |

In your experience, are fact-checking notes effective at countering misinformation on social media? Why or why not? If you were in charge of a social media platform, how would you moderate false or harmful content? What skills are useful with fact-checking or verifying information?

★ NLP Resources:

“Misinformation” (Checkology virtual classroom)

Classroom activity: “Fact-check it!”

| Related: |

- “Meta shift from fact-checking to crowdsourcing spotlights competing approaches in fight against misinformation and hate speech” (The Conversation).

- “Fact-checkers are among the top sources for X’s Community Notes, study reveals” (Poynter).

- “TikTok removes videos promoting birth control misinformation after The Independent investigation” (The Independent).

★ Featured classroom resource:

|

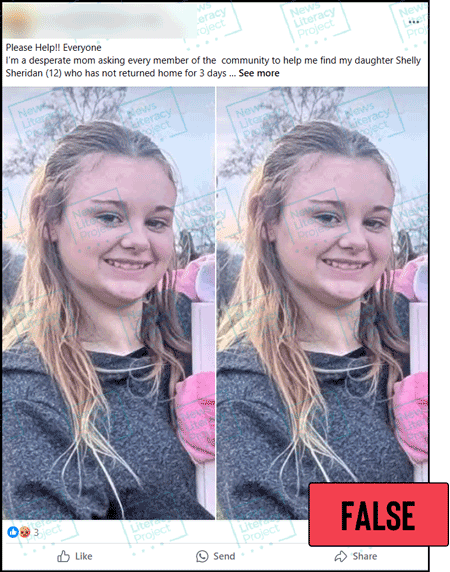

False posts about a missing child spread common online scam

❌ NO: The photographs included in these posts do not show a 12-year-old named Shelly Sheridan who went missing in England.

✅ YES: These photographs actually show a 16-year-old from the United States who briefly went missing in Kentucky in January 2025.

❌ NO: There have not been any police reports or credible news reports about a missing child of this name in England.

✅ YES: Similar social media posts about missing children or other emotionally charged topics that go viral are often online scams with malicious links and bogus offers.

★ NewsLit takeaway

Topics that evoke a strong emotional reaction – such as the disappearance of a child – are frequently exploited by purveyors of misinformation. These posts generate a lot of interest and are often accompanied by requests to “like” and “share,” ensuring they reach a wide audience, which then finds malicious links and scam offers once they click on them. Here are a few tips to avoid these like-farming scams:

Examine the details: The scams often contain obvious errors. In this case, the child above was identified as both “Shelly” and “Sarah” in the viral post.

Look for supporting evidence: It’s likely that a police report or a news article would be filed in the event of a child’s disappearance. If these items are absent, be skeptical of the claim.

Use a reverse image search: Plugging an image from a post into a reverse image search engine reveals important context. Fact-checkers found that this image is from news reports about a missing child in the U.S.

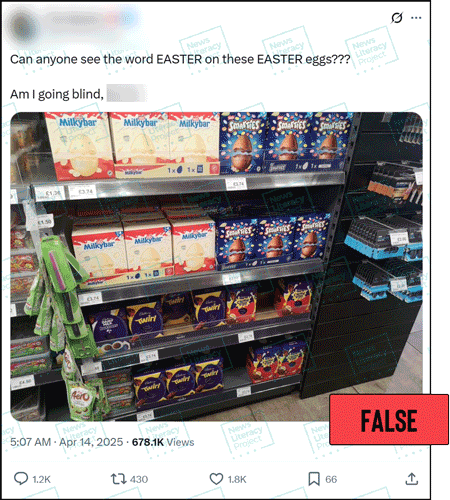

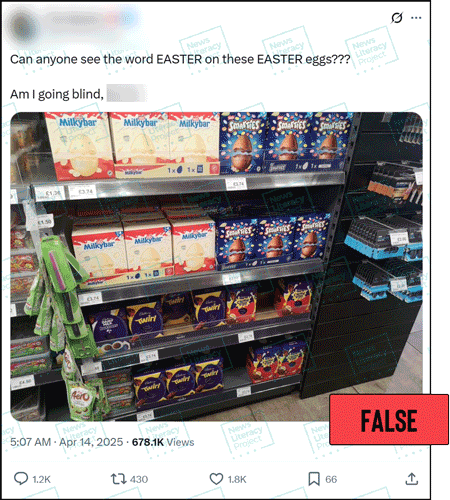

No, Cadbury didn’t stop using ‘Easter’ on its chocolate eggs

❌ NO: Cadbury has not stopped using the word “Easter” in its entire holiday candy collection.

✅ YES: Cadbury continues to cite Easter in its marketing and has done so for more than 100 years.

✅ YES: False claims that the company removed “Easter” from all of its packaging have been circulating online since at least 2016.

✅ YES: The boxes of Cadbury eggs in the above-displayed photograph (bottom two rows) show the word “Easter” on the top of the boxes.

★ NewsLit takeaway

When a social media post provokes a strong emotional reaction, such as outrage, people are more likely to engage with the content and less likely to critically examine it. Here are a few tips to avoid this:

Look beyond the photo: Viral posts often use a single image presented out of context. Check for additional details — such as the product listings on Cadbury’s website — to find out more.

Consider the source: If you aren’t familiar with the account sharing a piece of content, examine its profile and evaluate its other posts to determine if it is trustworthy.

Check the evidence: The image in the post used to support the claim that “Easter” is no longer used in Cadbury’s packaging doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Taking a closer look shows that “Easter” is visible on the boxes in the bottom two rows.

| Ten-dollar Birkenstocks, anyone? Viral TikTok videos claim you can avoid the middleman and buy Chinese-made goods directly, but they’re often a consumer scam preying on Americans with tariff anxiety. | |

| Sticky situation: A scientist paid to study maple syrup has also promoted it on social media, making misleading claims about how maple syrup may help stave off cancer and diabetes. | |

| Sixty percent of Americans surveyed by Pew Research Center say tech companies should help restrict false information online, and 51% say government should also do so, but support has declined since 2023. | |

| The White House recently removed wire news services — including Reuters, Bloomberg News and The Associated Press — from their permanent slot in the White House press pool. | |

| Misinformation researchers have developed an English and Indonesian version of a WhatsApp-inspired game, Gali Fakta, that “prebunks,” or inoculates, players against misinformation by teaching them to think critically about headlines. | |

| Who writes headlines? Editors often do it at news outlets, but at NPR there’s a collaborative headline-writing process, according to the NPR Public Editor newsletter. | |

| Eight out of 10 of the most popular online shows — including Joe Rogan’s — have spread climate misinformation, according to a Yale Climate Connections analysis. | |

| As headlines around the world focused on the death of Pope Francis on April 21, Jon Allsop of Columbia Journalism Review reflected on the late pope’s relationship with the press, including Francis’ support of press freedoms and his concerns about misinformation and polarization during his papacy. |

Thanks for reading!

Your weekly issue of The Sift is created by Susan Minichiello (@susanmini.bsky.social), Dan Evon (@danieljevon), Peter Adams (@peteradams.bsky.social), Hannah Covington (@hannahcov.bsky.social) and Pamela Brunskill (@PamelaBrunskill). It is edited by Mary Kane (@mk6325.bsky.social) and Lourdes Venard (@lourdesvenard.bsky.social).

You’ll find teachable moments from our previous issues in the archives. Send your suggestions and success stories to [email protected].

Subscribe to this newsletterSign up to receive NLP Connections (news about our work) or update your subscription preferences here. |

Check out NLP's Checkology virtual classroom, where students learn how to navigate today’s information landscape by developing news literacy skills.