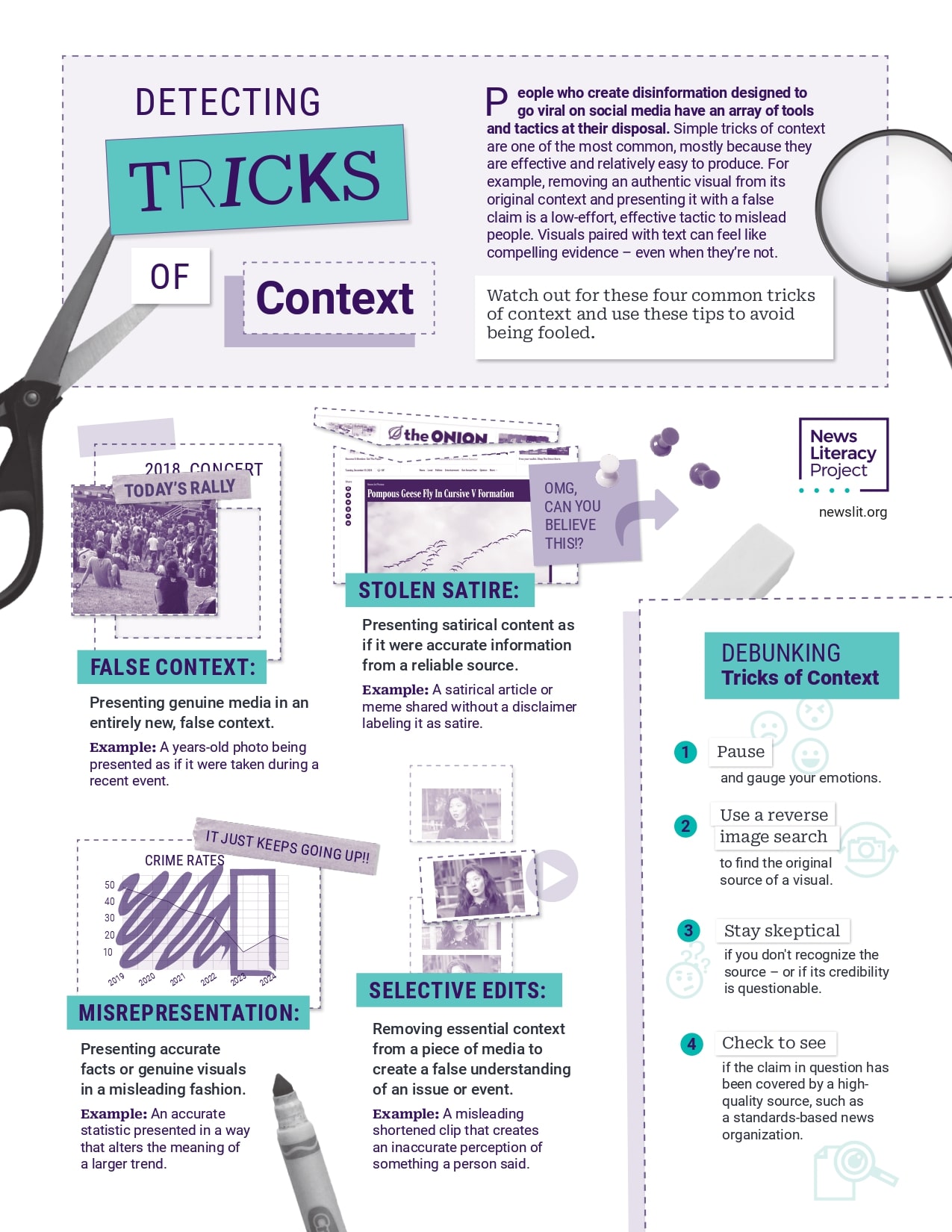

Detecting tricks of context

People who create disinformation designed to go viral on social media have an array of tools and tactics at their disposal. Simple tricks of context are one of the most common, mostly because they are effective and relatively easy to produce.

Watch out for these four common tricks of context:

- False context: Presenting genuine media in an entirely new, false context.

- Example: A years-old photo being presented as if it were taken during a recent event.

- Misrepresentation: Presenting accurate facts or genuine visuals in a misleading fashion.

- Example: An accurate statistic presented in a way that alters the meaning of a larger trend.

- Stolen satire: Presenting satirical content as if it were accurate information from a reliable source.

- Example: A satirical article or meme shared without a disclaimer labeling it as satire.

- Selective edits: Removing essential context from a piece of media to create a false understanding of an issue or event.

- Example: A misleading shortened clip that creates an inaccurate perception of something a person said.

This infographic also includes a list of tips to debunk tricks of context and avoid being fooled.

Evaluate credibility using the RumorGuard 5 Factors

Don’t get caught off guard. Recognize misinformation and stop it in its tracks by using RumorGuard’s 5 Factors for evaluating credibility of news and other information. This classroom poster displays the 5 Factors alongside “Knows” and “Dos” for evaluating credibility.

Learn about RumorGuard | Go to RumorGuard | The 5 Factors on RumorGuard

The 5 Factors

- Authenticity. Is it authentic?

The digital age has made creating, sharing and accessing information easier than ever before, but it’s also made it easier to manipulate and fabricate everything from social media posts to photos, videos and screenshots. The ability to determine whether something you see online is genuine, or has been doctored or fabricated, is a fundamental fact-checking skill.

- Source. Has it been posted or confirmed by a credible source?

Not all sources of information are created equal, but it can be easy to glaze over the significant differences while scrolling through feeds online. Standards-based news organizations have guidelines to ensure accuracy, fairness, transparency and accountability. While these sources aren’t perfect, they’re far more credible and reliable than sources that have no such standards. Viral rumors that confirm one’s perspectives and beliefs or that repeatedly appear in social media feeds can feel true, but if no credible source of information has confirmed a given claim it’s best to stay skeptical.

- Evidence. Is there evidence that proves the claim?

Misinformation lacks sound evidence by its very nature — but it often tricks people into either overlooking that fact or into accepting faulty evidence. Many false claims are sheer assertions and lack any pretense of evidence, while others present digital fakes and out-of-context elements for support. Evaluating the strength of evidence for a claim is a key fact-checking skill.

- Context. Is the context accurate?

Tricks of context are one of the most common tactics used to spread misinformation online. Authentic content — such as quotes, photos, videos, data and even news reports — is generally easy to remove from its original context and place into a new, false context. For example, an aerial photo of a sports championship parade from 2016 can easily be copied and reposted alongside a claim that it depicts a political protest that took place yesterday. In this false context, the photo may easily be perceived as genuine by unsuspecting people online. Luckily, there are easy-to-use tools that can verify the original context of most digital content.

- Reasoning. Is it based on solid reasoning?

Misinformation is often designed to exploit our cognitive biases and vulnerability to logical fallacies. These blind spots in our rational thinking can make baseless conclusions feel plausible or even undeniable — particularly when they reinforce one’s beliefs, attitudes and values. Conspiracy theorists, pseudoscience wellness influencers and propagandists commonly rely on flawed reasoning to hold their assertions together. Learning to logic-check claims is an important element in verifying information.

Know and do

Know:

• Standards of quality journalism

• Types of misinformation

• How cognitive biases work

• What makes evidence credible

Do:

• Reverse image search

• Lateral reading

• Critical observation

• Search internet archives

• Practice healthy skepticism

Three types of election rumors to avoid

Elections are the lifeblood of democracy, but political campaigns are often rancorous, controversial and polarizing events. As if the misleading claims and attack ads weren’t challenging enough for the public, bad actors further muddy the waters by pushing disinformation into our social media feeds.

These harmful falsehoods are designed to cause confusion and to undermine people’s faith in American democracy. Election disinformation can be tricky, but the same false narratives and claims tend to get recycled, which can make it easier to spot.

This infographic outlines three common types of election disinformation that are likely to circulate on social media during election cycles in the United States. It also includes tools and tips for locating credible information in your state or district.

Being familiar with recurring election disinformation themes can help inoculate you against the allure of new incarnations and iterations that occur regularly. It can also help you more efficiently debunk them and warn your friends and family members not to get taken in.

The three types of election disinformation this infographic focuses on are:

- “Ballot mule” accusations: A substantial portion of election misinformation revolves around baseless claims of voter fraud. Accusations of people (“mules”) illegally gathering large numbers of fraudulent ballots and delivering them to ballot drop boxes have become particularly common, despite the fact that such allegations lack evidence. More often, people who are authorized to return multiple ballots — such as designated agents for nursing home residents — are incorrectly portrayed as engaging in schemes to swing elections. Be wary of photos and videos of people delivering ballots that are framed as “evidence” of this type of fraud, which is extremely rare.

- Mail-in ballot rumors: Voting by mail is increasingly popular, but people are vulnerable to believing baseless allegations of mishandling ballots, partly because the chain of custody is less direct than with in-person voting. But mail-in voting is no less secure than in-person voting and examples of fraud remain rare (usually involving someone attempting to return a mail-in ballot previously requested by a since-deceased relative or housemate). If you see a claim about fraudulent mail-in voting, be extremely cautious and take time to verify it at least one credible source.

- Poll worker rumors: The increase in livestreams of election workers doing their jobs has given lots of raw fodder to strong partisans looking for anything they can construe as fraud. Keep in mind that there is legitimate and necessary election work that ordinary people are unfamiliar with and don’t entirely understand. Watch out for video clips and images out of context claiming that poll workers are manipulating the vote.

Don’t forget to check out the resources linked throughout the infographic, including ballot trackers, studies of actual fraud (which, again, is extremely rare) and analyses of viral election misinformation.

News Lit Quiz: Should you share it? Education edition

In brief: Misinformation

Few problems with our information environment are more pressing or prominent than the proliferation of misinformation online. False and misleading content is often designed to target our emotions and use our biases against us, exploiting our most deeply held beliefs and values to bypass our critical, rational thought processes.

But thinking and learning about misinformation can be challenging. Partisans lob strategic accusations of “fake news” at ideas they disagree with, or at news coverage they want to discredit. Social media platforms that have policies against misinformation fail to enforce them in ways that are consistent and effective. Bad actors who create and purposefully amplify disinformation do so for a variety of reasons, including political or financial gain or to simply to cause confusion and social division. They also employ an array of disinformation tactics and cover their tracks in clever ways.

This infographic is designed to help you get your bearings in the misinformation landscape. Why do people share misinformation? What is the difference between misinformation and disinformation? What are some of the different types of misinformation people regularly encounter online? What are some “red flag” phrases and other signs of dubious content that can help people recognize when to remain skeptical and proceed with caution.

It’s important to keep in mind that academic research into mis- and disinformation is ongoing, and our understanding of people’s information habits — including why they might be vulnerable to false and misleading content and motivated to share it — is improving over time.

Misinformation itself is also always changing, attaching itself to current events and controversial issues that gain prominence in the news cycle or national conversation. However, many of the strategies of misinformation — including placing photos, videos and quotes in false contexts, and doctoring or manipulating content — remain the same and can become recognizable with practice.

This infographic is designed to provide a foundational understanding of this urgent problem and help people be more mindful about their information habits.

“TRUST ME” discussion guide on manipulation and misinformation (collegiate guide)

About the film

About the film

Misinformation is all around us, and it has real-world consequences. In today’s information landscape where anyone can publish almost anything, who — and what — can you trust?

“TRUST ME” is a feature-length documentary directed by Oscar-nominated Roko Belic that delves into the topics of manipulation and misinformation by exploring human nature, information technology, and the need for news and media literacy to help people trust one another. The film was produced by the Getting Better Foundation, whose mission is to build trust using the truth. For additional information about the film or its producers, or to get involved, go to the film’s website.

The film is available for purchase from New Day Films: “TRUST ME“.

About this guide

This guide was produced by the News Literacy Project (NLP) and Pamela Brunskill with support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

The guide is intended for adult learners in all settings, such as colleges, correctional facilities and community forums. Leaders should adapt, adopt and adjust these recommendations and ideas as they see fit.

The discussions we recommend are broken up into three sections: before viewing, during viewing and after viewing to help you establish, and build on, the core concepts in the film and reflect on the questions that result. Extension and further reading opportunities are listed at the end of the guide.

“TRUST ME” classroom guide: A unit on manipulation and misinformation

About the film

About the film

Misinformation and disinformation are all around us, and have real-world consequences. In today’s information landscape where anyone can publish almost anything, who — and what — can you trust?

“TRUST ME” is a feature-length documentary that delves into the topics of manipulation and misinformation by exploring human nature, information technology, and the need for news and media literacy to help people trust one another. The film was produced by the Getting Better Foundation, whose mission is to build trust using the truth. For additional information about the film or its producers, or to get involved, visit TRUSTMEdocumentary.com and GettingBetterFoundation.org. The film is available for purchase from New Day Films.

The education cut of the film that accompanies this guide includes 15 segments. Depending on your schedule and objectives, you can show the full documentary or share it in segments.

About this guide

This guide was produced by the News Literacy Project (NLP) and Pamela Brunskill with support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, which also funded the distribution of the education cut of the film.

The guide is intended for students in grades 4-6, 7-9, and 10-12+. The lessons are delineated for a particular grade band when appropriate and are designed for teachers to adapt, adopt, and adjust as they see fit.

The lessons are broken up into three sections: before viewing, during viewing and after viewing to allow for scaffolded development of concepts and understanding. Extension and further reading opportunities are listed throughout each of these sections.

“TRUST ME” discussion guide on manipulation and misinformation (for parents and caregivers)

About the film

About the film

Misinformation is all around us, and it has real-world consequences. In today’s information landscape where anyone can publish almost anything, who — and what — can you trust?

“TRUST ME” is a feature-length documentary directed by Oscar-nominated Roko Belic that delves into the topics of manipulation and misinformation by exploring human nature, information technology, and the need for news and media literacy to help people trust one another. The film was produced by the Getting Better Foundation, whose mission is to build trust using the truth. For additional information about the film or its producers, or to get involved, go to the film’s website.

The film is available for purchase from New Day Films: “TRUST ME“.

About this guide

This guide was produced by the News Literacy Project (NLP) and Pamela Brunskill with support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

The guide is intended for parents and caregivers to aid in discussing the film with their families or other caregivers. They should adapt, adopt, and adjust these recommendations and ideas as they see fit.

The discussions we recommend are broken up into three sections: before viewing, during viewing and after viewing to help you establish, and build on, the core concepts in the film and reflect on the questions that result. Extension and further reading opportunities are listed at the end of the guide.

Fighting falsehoods on social media

The quiz embedded below measures how you know social media platforms’ policies designed to stem falsehoods from flooding your newsfeed. Different tech companies take different approaches, with some being more vigilant than others. In addition to implementing and enforcing their own policies, some platforms allow you to report misleading posts or provide information about the people and/or organizations that manage the page, including where they are located, when the page was created, whether the page has had other names, and whether it is running ads?

More important than ever

We have seen just how important such policies and tools are in 2020, with plenty of misinformation circulating about COVID-19, racial justice protests, wildfires and the presidential election.

For example, when you search “coronavirus” or “COVID-19” on certain platforms —you’ll learn which ones in the quiz — post from authoritative health sources or standards-based news organizations are prioritized at the top of the results. One social media platform has a “medical misinformation” option in its content reporting menu, and others are expected to follow suit.

Different approaches to political advertising

Falsehoods, rumors and manipulated content about elections, campaigns and politicians are nothing new, and some companies are working to keep such misleading content off their platforms. And one tech company banned political ads last fall, arguing that the reach of political messages should not be bought through internet advertising. But another online giant has taken a lenient approach to political advertising. Its policy has exempted politicians’ posts and ads from the company’s third-party fact-checking program because they are considered “newsworthy” even if they are untrue.

So take this quiz and see how much you know about the social media sites that you visit and the measures they are taking to protect the public. You might be surprised by how much you know or don’t know!

Five types of misinformation

The term “fake news” once referred to misinformation designed to look like legitimate news, but the term has been rendered meaningless and counterproductive through overuse and political weaponization. The reality is that different kinds of misinformation vary significantly in their tactics, intent and impact. Therefore, to better understand misinformation, we need a new vocabulary that helps us see and think about these differences.

The term “fake news” once referred to misinformation designed to look like legitimate news, but the term has been rendered meaningless and counterproductive through overuse and political weaponization. The reality is that different kinds of misinformation vary significantly in their tactics, intent and impact. Therefore, to better understand misinformation, we need a new vocabulary that helps us see and think about these differences.

The poster linked below identifies and defines five types of misinformation:

- Satire

- False context

- Impostor content

- Manipulated content

- Fabricated content

Definitions and examples of each type of misinformation are included in the poster linked below. This poster was adapted from the “Misinformation” lesson on our Checkology® virtual classroom. Use it with that lesson or on its own.

Sanitize before you share

Misinformation swirling around the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the importance of consuming and sharing online content with care.

Misinformation swirling around the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the importance of consuming and sharing online content with care.

Public health officials are urging us to practice good hygiene to help stop the spread of this virus — by washing our hands thoroughly and frequently, staying home as much as possible, and keeping a safe distance from others when we do go out.

We can also practice good information hygiene.

Just adopt the four quick and easy steps below to help stop the spread of COVID-19 misinformation. If we sanitize the process around our information habits, we can prevent misleading and false content — some of which is hazardous to our health — from being widely shared and potentially doing harm.

Get smart about COVID-19

Each of us needs to play a role in combating misinformation about the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. When the outbreak hit the U.S. in spring, NLP created resources to provide the public, educators and students with accurate information about the illness.

We also created a quiz to test whether you can sort fact from fiction related to COVID-19 information. The World Health Organization called this deluge of information and misinformation about the pandemic an “infodemic’ for good reason.

Test your knowledge

The quiz embedded below will test your ability to accurately categorize information using a compilation of examples pulled from several sources. You will see news clips, social media posts, images, video, and charts and graphics. Then you must determine whether the content is opinion or news, is supported by valid evidence or whether the source cited is reliable.

If you have been paying attention to news about the pandemic these many months, you might find that some of the examples are easy. Yet others just might trip you up. Remember, this virus poses an ongoing and serious public health challenge. Since it appears COVID-19 will be with us for a while, it’s important to keep your skills sharp when it comes to determining what to trust, share or act on.

Your health and the health of your friends and family might just depend on it.

Should you share it?

When a news event or a significant issue grabs hold of the public’s attention, it’s human nature for us to want to get our hands on as much information as we can as fast as we can. It’s also human nature to act on an impulse to share that information with friends, family and the wider community in an effort to keep people safe from harm.

Unfortunately, large breaking news events — especially those connected to controversial, frightening and complex subjects, like the current COVID-19 pandemic — tend to generate a spike in viral rumors. These stories, anecdotes, ads and memes pass quickly from one person to the next, often with little regard to whether the content is true. Some elements may be accurate, but much is simply a form of digital rumor — half-truths, doctored videos and images, or complete fabrications.

Check your emotions and think critically

They typically appeal to our emotions, provoking anger, fear, curiosity or hope and overriding our rational minds and critical-thinking skills. When we have an immediate strong response to a piece of content online, our impulse is to take action: to “like” it, to share it immediately, to express whatever we’re feeling about it. Because of that impulse, and because Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and other platforms effortlessly connect us to thousands of people (many of whom we’ve never even met), this content spreads rapidly across social media — even from one platform to another.

So think of these rumors like an actual virus. Mike Baker, a New York Times reporter in Seattle, has been tweeting weekly about the exponential increase in confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States. A “like,” share or retweet of false or unverified content on social media spreads the same way — and the numbers are considerably larger.

About the film

About the film About the film

About the film About the film

About the film