‘War of the Worlds’ broadcast kicked off lasting myth

Imagine hearing this startling “news” while relaxing at home on a Sunday evening: “… those strange beings who landed in the Jersey farmlands tonight are the vanguard of an invading army from the planet Mars.”

If you were listening to CBS Radio’s Mercury Theatre on the Air program 81 years ago today, that’s exactly what you would have heard. That evening in 1938, host Orson Welles broadcast an adaptation of The War of the Worlds, the H.G. Wells novel about a Martian invasion of Earth.

At the time, newspapers reported that millions of listeners had believed that a Martian attack really was underway, resulting in mass hysteria. The stories claimed that thousands had fled their homes in panic, the stories claimed.

In truth, the broadcast created little panic. Most listeners understood that it was a dramatization, even though it was described as such only once during the program.

So was coverage of this “fake news” actually fake news? Apparently so.

No mass hysteria

A 2013 article in Slate blamed the mass panic myth on heated competition between newspapers and radio, the relatively new electronic medium that was gobbling up advertising dollars. “The newspaper industry sensationalized the panic to prove to advertisers, and regulators, that radio management was irresponsible and not to be trusted,” according to the authors Jefferson Pooley and Michael J. Socolow.

Ironically, what actually fooled people was not the program itself, but the false coverage of it. While today’s media landscape is nothing like it was in 1938, misinformation persists, and thrives, thanks to the multiplying factor of social sharing.

But news literacy education can counter this phenomenon by teaching us to discern the credibility of information and embrace some healthy skepticism (for example, NewseumED offers a “War of the Worlds”-themed activity). In fact, Welles ended his infamous broadcast with a nudge to do just that: “…if your doorbell rings and nobody’s there, that was no Martian. . . it’s Hallowe’en.”

Curriculum Connection: Facebook, satire and fact-checking

The Wall Street Journal reported last week that Facebook plans to exempt satire and opinion content from its fact-checking program. This would mean that posts that contain demonstrably false claims, but which the platform deems to be either satire or opinion, would not be referred to its network of third-party fact-checkers.

Thus, Facebook would not downgrade this content in its algorithm, and fact-checks would not appear alongside them.

News of the expected policy change came just a week after Facebook, citing a “newsworthiness exemption,” said it would continue to exempt politicians’ posts from its fact-checking program. The exemption would not apply if the politician shares “previously debunked content.” In such cases Facebook would demote the post and would display fact-checking information.

It also follows several contentious incidents involving satirical and opinion content and the company’s third-party fact-checking partner. This includes a debate in July between Snopes and the Christian satire site The Babylon Bee. Another example is a disagreement in August between Health Feedback, which focuses on accuracy in health and medical coverage, and Live Action, an anti-abortion group.

Fact-checking debate

At issue is an ongoing debate about whether satirical and opinion content should be fact-checked, and how Facebook plans to determine which publishers and posts to exempt. A study published in August by three Ohio State University researchers found that false satirical claims are believed by a significant number of people. This is no doubt partially because people don’t always recognize the satirical sources they see on social media. It is also because satire is often insufficiently labeled or is copied and shared out of context.

“Fake news” websites that engage in wholesale plagiarism of satirical pieces as clickbait for ad revenue is well-documented. But individual elements of these stories also go viral. For example, a fake tweet attributed to President Donald Trump and created as a graphic for a piece by a Canadian satire site, The Burrard Street Journal, has a life of its own. (The comments on the piece itself seem to indicate that it, too, was mistaken as legitimate reporting).

Those who intentionally spread disinformation online often claim to have been joking, or merely sharing an opinion, once fact-checkers call them out. That makes Facebook’s enforcement of this anticipated new policy even more difficult.

“Live-trolling”

Satire took on another form when an activist from the far-right conspiracy group LaRouche PAC engaged in a piece of “live-trolling” at a town hall hosted last Thursday by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-New York). The group later claimed the activity was satirical.

Discuss

Do false claims on Facebook based on a staged “satirical” stunt qualify as satire under its new policy? Would a clip or a meme of the satirical performance presented out of context be protected under the new policy?

Go deeper

Put students in the place of decision-makers at Facebook and ask them to issue a ruling for the following cases. Which would they exempt under the platform’s policies, either anticipated or existing, regarding satire, opinion and statements by public officials?

- A well-known satire publication publishes a genuine piece of satire. People online largely mistake it as legitimate. It is clearly labeled as satire in the URL preview on the platform.

- An obscure satire publication posts a genuine piece of satire. People largely mistake it as legitimate. It is not clearly labeled as satire.

- A single element — such as a doctored photo or a fake tweet — of a legitimate satire piece is copied and goes viral outside of its original satirical context.

- An individual celebrity, known for pulling online hoaxes, posts a satirical video that many people mistake as serious.

- A politician repeats a false claim that originated in a satirical publication, but doesn’t attribute it.

- An online troll posts a piece of misinformation but says it’s just a joke.

- A partisan activist posts a piece of misinformation but says that it illustrates an opinion about a larger truth.

Learn more

“Opinion: Facebook just gave up the fight against fake news” (Brian A. Boyle, Los Angeles Times)

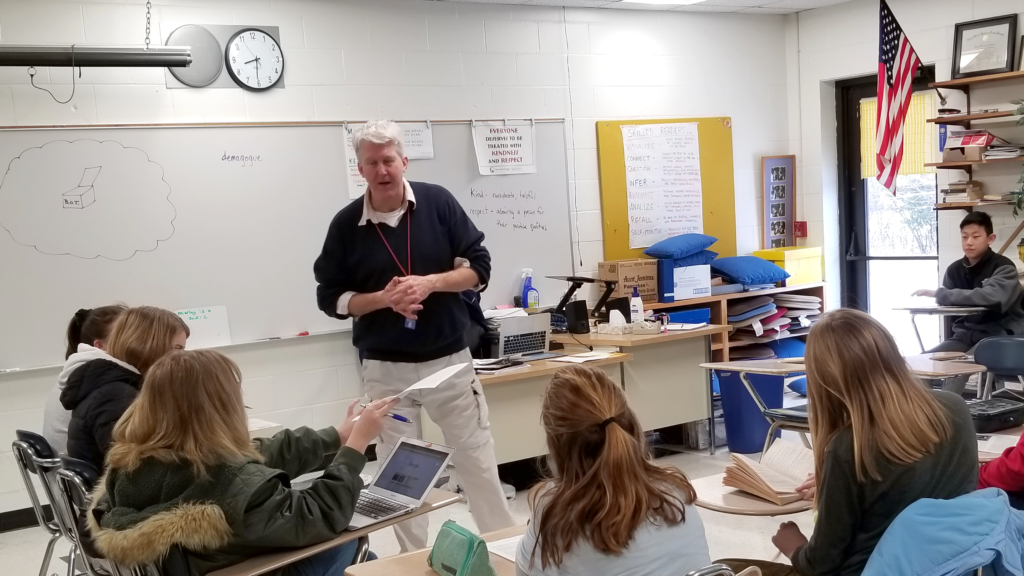

Bringing news literacy to a school, one freshman class at a time

Like many teens asked to research a topic, Catherine Griffin’s students typically would open a search engine, type a word or phrase, and simply use the source at the top of their results.

But once Griffin guides them through the Checkology®virtual classroom, they start digging deeper, citing scholarly articles and database results in their research.

“I think students rush research sometimes, and Checkology just gets them to slow down and process information,” said Griffin, whose class, Computer Essentials, is required for ninth-graders and transfer students at Algonquin Regional High School.

The public school serves the Boston suburbs of Northborough and Southborough, Massachusetts, home to about 25,000 residents. This year, thanks to Griffin and two other educators, all 1,400 students at Algonquin will have completed Checkology’s lessons.

A fundamental skill

The school sees news literacy as a foundational skill and uses the platform as a precursor to an information literacy unit in which students produce a research paper.

“We’re very lucky,” Griffin said. “We’re all thrilled to have the backing of our superintendent, principal and parents who think this is an essential skill.”

She first heard about Checkology in 2016 from the chair of the school’s social studies department, who wanted to use it but couldn’t find time for it in her teachers’ packed curriculum of required lessons. As a certified social studies teacher, Griffin immediately grasped the benefit of news literacy education — and thanks to the greater flexibility afforded by her Computer Essentials course, she has been able to take her students through Checkology in its entirety over a period of three to four weeks.

“It’s an impact that I see right away,” she said. “They’re researching all the time. Questioning: ‘Who wrote it?’ ‘When was it published?’ ‘Who is this guy?’ ‘What is his profession?’ Whether they go to college or get a job, this is a skill they have to have.”

Customizing Checkology

Griffin has customized her approach to Checkology, kicking off the lessons by sharing the results of the 2016 Stanford History Education Group study (PDF) that found a lack of news literacy skills in teens and then having students watch Eli Pariser’s TED Talk on filter bubbles — the algorithmic bias that restricts what an individual user sees online. From there, she aims to complete all 13 lessons, blending in her own assignments along the way. She says the platform’s flexibility is one of its greatest assets.

“You can do it as a group, or we can have days when they are doing it on their own,” she said. “They can access it at home — anywhere they have a computer.”

Even when students are working independently in her classroom, Griffin said, she will see them talking to their neighbor or getting up and walking across the room to discuss a lesson or question with their friend.

“It’s so current, so it’s things they know or have heard of,” she said.

It also introduces them to journalism concepts and terms. “The vocabulary is huge for them,” she said. “Propaganda — knowing what it is. Bias. The word ‘provoke’ came up, and they weren’t sure what it meant.”

A Checkology ambassador

Griffin has become something of a news literacy ambassador in her home state. A couple of years ago, she and a colleague spoke at MassCUE, an annual statewide conference for “computer-using educators.” They led a breakout session on media literacy to a packed room; the bulk of their presentation was focused on Checkology, including a walk-through of the introductory lesson, “InfoZones.” It was, Griffin said, the most crowded session of the conference.

Afterward, she received about a dozen emails from educators wanting to know more. “There is a huge need for this among teachers,” she said.

Checkology has also changed how Griffin approaches information. Now, she said, when she does research, she goes through a checklist of different things to look for. She’s more thoughtful about the sources she consults. She’s more careful in verifying the information she brings to her classroom.

“We teach our students to read,” she said. “News literacy is the same thing. It’s reading and understanding. It is a necessity for these students who will be citizens and make decisions.”

Curriculum Connection: Examining the impact of rising government disinformation

Political parties or government agencies in 70 countries are using “cyber troops” to engage in organized disinformation efforts online, according to a new report from the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford. This is a 150% increase in state- and party-sponsored social media manipulation campaigns since 2017. At that time researchers found such activity in only 28 countries.

Among the key findings:

- Facebook (56 countries) and Twitter (47 countries) are by far the most popular platforms for these efforts.

- A strong majority of countries use human-operated (61 countries) and automated (bot) accounts (56 countries).

- Attacking political opponents (63 countries) is a significantly more common use of computational propaganda than spreading messages that support a government or party (51 countries). (Computational propaganda is defined [PDF] as “the use of algorithms, automation and human curation to purposefully distribute misleading information over social media networks.”)

The report also found that most countries use a combination of tactics in these campaigns. Fifty-five countries create and circulate misinformation, such as memes and “fake news” websites. Fifty-two countries amplify content, including legitimate news, that aligns with government or party interests. And 47 countries employ targeted trolling of journalists and people with opposing opinions.

Often, government and political figures employ “cyber troops” who work with private industry, social media influencers and online communities. And some enlist students and private citizens to post specific messages to social media accounts.

Disinformation training

In addition, the study found several cases in which countries with more established disinformation programs — such as Russia, India and China — provided training and other assistance to countries with upstart disinformation programs.

For educators

Discuss: The report points out that a “strong democracy requires access to high-quality information and an ability for citizens to come together to debate, discuss, deliberate, empathize, and make concessions.” Why are misinformation and disinformation considered threats to democracy?

For further consideration: The final lines of the report pose two key questions that provide an excellent way to spark student engagement.

- “Are social media platforms really creating a space for public deliberation and democracy?”

- “Or are they amplifying content that keeps citizens addicted, disinformed, and angry?”

Activity: Have students reimagine a historic propaganda campaign with access to today’s information environment. Refer to those created during World War II or the Cold War. How would it be different? How might history have been different?

Related: “Disinfo bingo: The 4 Ds of disinformation in the Moscow protests” (Lukas Andriukaitis, Digital Forensic Research Lab, Atlantic Council.)

Curriculum Connection: Complex Kavanaugh story gets tangled in the telling

On Sept. 14, The New York Times published an essay by two of its reporters, Robin Pogrebin and Kate Kelly, that was based on their new book, The Education of Brett Kavanaugh: An Investigation. The Times’ opinion section — which is responsible for the Sunday Review section, where the essay appeared — also posted a tweet promoting the piece. Both the tweet and the essay sparked a firestorm of outrage and criticism across the political spectrum and exposed a series of flawed editorial decisions and blunders.

Within minutes of the posting, @nytopinion deleted it, calling it “poorly phrased.” (It asked whether exposing male genitalia in someone’s face might be considered “harmless fun.”) Soon thereafter, the second tweet also was deleted. Later that evening, @nytopinion described the original tweet as “offensive” and apologized. On Sept. 17, and said it was “misworded.”

Omissions and corrections

The essay also included a new allegation of sexual misconduct against Kavanaugh when he was in college. Some readers were perplexed that the Times hadn’t made this new allegation the focus of the piece. In addition, the essay omitted two important facts included in the book. The female student did not recall the incident, according to friends, and she had declined to be interviewed. The Times later added those details to the essay, along with an Editors’ Note.

Kelly and Pogrebin told MSNBC that there was no intention to mislead anyone, and that the omission occurred while the essay was being edited. The book identifies the female student by name. The Times typically does not do so in such cases. “In removing her name, they removed the other reference to the fact that she didn’t remember,” Pogrebin said of her editors during an appearance on The View.

One conservative publication contended that the Times was admitting to publishing “fake news” by adding the Editors’ Note and the omitted details. However, other outlets called the update a “correction.”

The new allegation led several Democrats running for their party’s presidential nomination to call for Kavanaugh’s impeachment. The Times did cover this development.

Pointing out the omission

News outlets credited Mollie Hemingway, a senior editor at The Federalist, a Fox News contributor and a co-author of Justice on Trial: The Kavanaugh Confirmation and the Future of the Supreme Court, for pointing out the omitted material. (Hemingway is a member of the News Literacy Project’s board of directors.)

Discussion points for teachers

Do you agree that The New York Times should have deleted the initial tweet? Why or why not? What do you think of the way the Times handled the essay and the new allegation it contained? What do you think of the way it handled the criticism? Do you think adding details to a story after initial publication counts as a correction? In its Editors’ Note, should the Times have explained how the omission occurred.?

Global Youth & News Media Prize honors Checkology

I’m delighted to tell you that our Checkology® virtual classroom has won a Silver Award in the News/Media Literacy category from the 2019 Global Youth & News Media Prize.

I’m delighted to tell you that our Checkology® virtual classroom has won a Silver Award in the News/Media Literacy category from the 2019 Global Youth & News Media Prize.

The Global Youth & News Media Prize, established in 2018, honors organizations around the world that innovate as they strengthen engagement between news media and young people while reinforcing the role of journalism in society.

The award — supported by the European Journalism Centre, the Google News Initiative and News-Decoder — recognizes initiatives that effectively educate about journalism and news media in ways that help young audiences navigate all kinds of content as they develop the news habits and knowledge that are key to becoming engaged participants in civic life.

Why Checkology won

In naming Checkology a 2019 laureate, the prize jury said: “We felt that this initiative achieved scale, impact and sustainability, which are rare things to find together in any media literacy programme. The virtual connection to journalists was an innovative and easy-to-access tool that we felt would have the ability to make a lasting impression on the students. Bravo!”

This honor is a further testament to NLP’s innovation and leadership in the field of news literacy. To learn how we plan to continue to scale our impact over the next three years and achieve our vision of embedding news literacy lessons in the American education experience, take a look at our Strategic Framework.

Other prize winners

Top Story of Kenya, a reality television show that features an investigative reporting competition for journalism students, also received a Silver Award. The top prize went to The Student View, a nonprofit based in the United Kingdom that teaches students to become investigative journalists to better understand disinformation.

Journalist of the Year honoree Acevedo ‘proud of the work that we’re doing together’

On Sept. 24, the same day that journalist Enrique Acevedo became a U.S. citizen, the News Literacy Project presented him with its John S. Carroll Journalist of the Year Award.

Acevedo, who was born in Mexico, is the co-anchor of Univision’s Noticiero Univision Edición Nocturna, the network’s late-night news program. He has been involved with NLP since 2017 — most recently at a NewsLitCamp® in April at Univision, where he led a workshop for educators on identifying bias in the news. He is also the host of the first Checkology® virtual classroom lesson offered in English and Spanish, “Practicing Quality Journalism”/ “Practicando el periodismo de calidad.” This game-like simulation lets students assume the role of a rookie reporter covering a breaking news event and is one of the most popular on the platform.

“I’m extremely proud of the work that we’re doing together. I’m grateful that you had the vision to record this lesson in Spanish and to reach a larger audience,” Acevedo said. “NLP is on the front lines on the war on truth and is helping this young audience understand their responsibility, both as consumers and producers.”

Award namesake

The John S. Carroll Journalist of the Year Award — named for one of the most revered newspaper editors of his generation — goes to journalists who have contributed significantly to NLP and its mission. A committee of NLP board members and staff select the honorees, who receive a glass plaque with an etched photo of Carroll and $500. During an acclaimed career spanning four decades, Carroll was the editor of three major U.S. newspapers — the Lexington (Kentucky) Herald-Leader, The Baltimore Sun and the Los Angeles Times. He was one of NLP’s first two board members and served as board chair until shortly before his death in 2015.

Alberto Ibargüen, president and CEO of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, and Jennifer Preston, the foundation’s vice president for journalism, joined Acevedo’s wife, journalist Florentina Romo, and Univision anchor Jorge Ramos at the award luncheon in Miami. Knight Foundation is NLP’s largest funder.

“With Alberto’s and Jennifer’s and Knight’s generous support and the help of outstanding journalists like Enrique, we’ve now reached well over 100,000 students, and we believe we’re on our way to reaching millions. John would be extremely proud,” said Alan C. Miller, NLP’s founder and CEO.

Student appreciation for Acevedo

While the award recognizes the significant role of journalists in our democracy, the program did have its lighter moments. Miller couldn’t resist sharing some of the particularly enthusiastic feedback from students who had completed the Checkology lesson Acevedo hosts:

- “It was really engaging and you kept on wanting to do more and more … I think this is the best lesson EVER!”

- “Enrique was pretty sharp-looking. He was like a Spanish Mark Ruffalo.”

- “Enrique is an angel among us sent forth to help us understand what quality journalism is.”

“So, Enrique, for being an outstanding journalist — as well as a Spanish Mark Ruffalo and an NLP angel sent to help us teach the next generation how to be news-literate — we are delighted to present you with the John S. Carroll Journalist of the Year Award,” Miller said.

Survey: Newsroom diversity lagging

Newsroom diversity continues to be a challenge for news organizations in the United States, according to the 2019 ASNE Newsroom Diversity Survey.

The American Society of News Editors received responses to its 41st annual survey from 429 news organizations. Both print/digital newsrooms and online-only outlets responded to the survey. The results (PDF download), released last Tuesday, found that people of color comprised 21.9% of salaried employees in 2018, compared with 21.8% the year before. Online-only news outlets surveyed said they had increased the racial diversity of their salaried employees by more than 6 percentage points, from 24.6% in 2017 to 30.8% in 2018.

Almost a fifth (19.1%) of newsroom managers at responding news organizations in 2018 were people of color, slightly higher than the previous year’s 17.6%. More than 40% of managers were women (compared with about 42% in 2017); 2% of managers identified as gender nonbinary.

The response rate increased in 2018: Almost a quarter (23%) of the 1,883 news outlets that received the survey returned it, up from 17% — a record low — the year before.

For teachers

Discuss: Is it important that the staffs of local newsrooms reflect the diversity of the community they cover? Why? Should newsrooms that cover communities that aren’t very diverse still make diversity a priority? Why or why not? What kinds of diversity should newsrooms focus on?

Idea: Contact local print and/or online news organizations and ask if they participated in the ASNE Newsroom Diversity Survey. If they didn’t, ask why, and whether they will next year. If they did, ask if they will share their data with your class.

Another idea: Another idea: Ask students to use the U.S. Census Bureau’s American FactFinder portal to research demographic information about their community. Then compare the census data with survey data from a local newsroom (if available) or with the ASNE survey results

Read more about newsroom diversity

- “There’s a gender crisis in media, and its threatening our democracy” (Katica Roy, Fast Company)

- “American newsrooms should employ more people of color, annual ASNE survey finds”

Legacies of Ifill, Pearl come together at Student of the Year Award ceremony

The lives and legacies of journalists Gwen Ifill and Daniel Pearl continue to influence the next generation, as evidenced by this year’s recipient of the News Literacy Project’s Gwen Ifill Student of the Year Award: Valeria Luquin, a 10th-grade student at Daniel Pearl Magnet High School.

The award features an etched photo of Gwen Ifill. Elyse Frelinger

“I’m extremely honored to have been nominated and to be receiving an award that commemorates the unforgettable journalist Gwen Ifill,” said Luquin, 15, during a luncheon on Sept. 17 at the Van Nuys, California, school. “She has left such a huge impact in the field of journalism, especially for women of color like myself, and has made them feel heard in the field.”

The award is presented to female students of color who represent the values Ifill brought to journalism. She was the first woman and first African American to serve as moderator of Washington Week and as a member (with Judy Woodruff) of the first female co-anchor team of a network news broadcast on PBS NewsHour. Ifill, who died in 2016, also was a longtime supporter of the News Literacy Project and served on its board.

Checkology’s impact

NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom was part of a journalism class that Luquin took in ninth grade. “Valeria has taken the lessons she learned from Checkology to heart,” said Alan C. Miller, NLP’s founder and CEO. “She has incorporated them in her work as a student journalist and with her family at home. She has become an upstander for facts and aspires to be a journalist herself.”

In the last year, said her teacher, Adriana Chavira, “I’ve seen her go from being a shy student to a blossoming young journalist. She’s really embraced the knowledge she’s learned from the News Literacy Project.”

Luquin said that Checkology has changed how she engages with information: “I think more critically and I question the credibility of information I hear. We should question the information we take in and be aware about what is occurring around us every day.”

In a video interview with NLP earlier this year, Luquin described how Checkology has had an impact on her life.

A personal connection

Valeria Luquin with NLP founder and CEO Alan Miller (left) and board member Walt Mossberg (right) Elyse Frelinger

Miller and NLP board member Walt Mossberg, a former Wall Street Journal reporter and columnist, presented Luquin with a $250 gift certificate and a glass plaque with an etched photo of Ifill during the award program. The communications and journalism magnet school is named for The Wall Street Journal’s South Asia bureau chief, Daniel Pearl, who was kidnapped and murdered by terrorists in Pakistan in 2002. The school was originally based at Birmingham High School, from which Pearl graduated in 1981.

Mossberg, who worked with Pearl in the Journal’s Washington bureau, also spoke to students in a journalism class. “I just get chills walking into this place,” he said, describing his onetime colleague as “really amazing, a wonderful man. He was a terrific journalist. The fact that this school exists and has his name on it means so much to me — and I’m sure to many others.”

Also attending the award ceremony were Alison Yoshimoto-Towery, interim chief academic officer of the Los Angeles Unified School District; Pia Cruz Sadaqatmul, director of LAUSD’s Local District Northwest; Margaret Kim, administrator of instruction for LAUSD’s Local District Northwest; Pia Damonte, principal of Daniel Pearl Magnet High School; and members of Luquin’s family.

Wondering if content is reliable? Determine its origin

Know the techniques bad actors use to fool you online.

The most essential question to ask of viral online content is also frequently one of the most difficult to answer: Where did this come from?

While this question isn’t new — after all, purveyors of misinformation have always “adapted their workflows to the latest medium” — it has been elevated by an information ecosystem optimized for anonymity, alteration, fabrication and sharing.

It’s a perfect storm, the authors of a new report argue, for “source hacking”: organized information influence campaigns that exploit “technological and cultural vulnerabilities” to strategically amplify — and obscure the provenance of — false information. The paper provides new vocabulary for common tactics employed by bad actors online: viral sloganeering (packaging and pushing claims and talking points); leak forgery (fabricating and “leaking” false documentation); evidence collages (selectively bundling information and examples from multiple sources); and keyword squatting (using sockpuppet impersonation accounts and flooding or “brigading” comments, keywords and hashtags to misrepresent issues, individuals or groups).

Used in combination, these tactics make it difficult to determine the origins of pieces of coordinated misinformation. Disguising the content’s creators and their intent helps false claims get amplified to large audiences by social media influencers and by news outlets debunking or otherwise covering the campaign. But this new vocabulary can help the public move beyond opaque and less useful terms — like “trolling” — to accurately describe and better understand coordinated disinformation efforts online.

Take, for example, the false rumor spread in the wake of a shooting spree in two West Texas towns on Aug. 31. When police identified the gunman the day after the shooting, a false claim quickly spread online (viral sloganeering) that he was a supporter of 2020 Democratic presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke. At one point, this claim comprised more than 13% of all tweets about shooter (keyword squatting). Doctored images of the shooter’s truck with an O’Rourke campaign bumper sticker emerged, as did screenshots of fake online profiles (WARNING: linked page includes examples of hate speech) listing false information about the shooter’s political affiliations and ethnicity (leak forgery). These claims were thencombined (evidence collage) and spread.

Here are some activities for the classroom:

Note: The false information about the Odessa, Texas, shooter is not the only recent example of Donovan and Friedberg’s source hacking techniques in action. Last week, NBC News traced a number of divisive social media accounts impersonating Jewish people back to 4chan’s /pol/ message board, a forum known to be a cauldron of anti-Semitism, sexism and racism.

Also note: The U.S. Department of Defense announced last week that disinformation is a significant enough threat to U.S. security that it is launching an initiative to repel “large-scale, automated…attacks.”

Discuss: Can breaking down and naming the techniques used by disinformation agents online help people better avoid being exploited by mis- and disinformation? Will knowing these four techniques help you?

Related:

- “Tracing Disinformation With Custom Tools, Burner Phones and Encrypted Apps” (The New York Times, featuring Matthew Rosenberg)

- “Disinformation and the 2020 Election: How the Social Media Industry Should Prepare” (Paul M. Barrett, Stern Center for Business and Human Rights, New York University)

- “Bots in Blackface — The Rise of Fake Black People on Social Media Promoting Political Agendas” (Samara Lynn, Black Enterprise)

California high school student named Gwen Ifill Student of the Year

Valeria Luquin, a high school sophomore who applies skills gleaned from the News Literacy Project’s Checkology® virtual classroom in her daily life, has been named NLP’s Gwen Ifill Student of the Year for 2019.

“Valeria has taken everything she’s learned on Checkology to heart,” said Alan C. Miller, NLP’s founder and CEO. “She not only has brought these lessons to bear on her work as a student journalist, but is now considering a career in journalism herself.”

The award commemorates Gwen Ifill, the trailblazing journalist — and longtime NLP supporter and board member — who died in 2016. It is presented to female students of color who represent the values Ifill brought to journalism as the first woman and first African American to serve as moderator of Washington Week and as a member (with Judy Woodruff) of the first female co-anchor team of a network news broadcast on PBS NewsHour. Honorees are selected by a committee of NLP staff and board members.

Luquin will receive the award — a $250 gift certificate and a glass plaque with an etched photo of Ifill — at a Sept. 17 lunch at her high school, the Daniel Pearl Magnet High School in Van Nuys. Pearl, The Wall Street Journal’s South Asia bureau chief, was kidnapped and murdered by terrorists in Pakistan in early 2002.

Checkology lessons were a weekly component of Luquin’s ninth-grade journalism class in the last school year. Her teacher, Adriana Chavira, called Luquin a “remarkable student who has taken her responsibility as a future journalist to heart. She is not afraid to question where people get their information from, and she makes sure she has facts from credible sources to support her reporting.”

Chavira recommended that Luquin join Miller to discuss misinformation on a local public affairs program, In Depth, broadcast on Fox 11 in Los Angeles in April. The show’s host, Hal Eisner, then invited Miller, Luquin and her mother, Lorena, to discuss news literacy in more detail on his podcast, What the Hal.

“I am so honored,” Luquin said when she was told about the award. “Receiving an award in honor of Gwen Ifill means a great deal to me. The legacy she left behind as a journalist inspires me, especially being a woman of color as well.”

In a video interview with NLP earlier this year, Luquin described how Checkology has had an impact on her life. “After doing Checkology, I feel I have gotten better at being a journalism student and identifying real news from fake news,” she said. “It actually makes me kind of want to be a journalist.”

She also said that she feels a need to help others think critically about information they consume and share: “I think I have the responsibility to identify whether different stories on the news are actually factual.”

She even has become an advocate for news literacy at home. For example, she told NLP how she had asked her father about the credibility of the sources in a documentary he had been watching. “He looked at me and told me, ‘I notice that you’ve gotten a lot more critical,’” she said. “That made me realize I do act more critical.”

Luquin also wants to set a good example for her 7-year-old sister: “I can tell she looks up to me, so it’s important that I’m a good role model.”

Enrique Acevedo of Univision named NLP’s 2019 John S. Carroll Journalist of the Year

Enrique Acevedo, co-anchor of Univision’s Noticiero Univision Edición Nocturna, the network’s late-night news program, is the 2019 recipient of the News Literacy Project’s John S. Carroll Journalist of the Year Award.

“Enrique made major contributions to NLP on important fronts in the past year with considerable skill and professionalism,” said Alan C. Miller, NLP’s founder and CEO. “And his work as a journalist reflects the high standards and enterprise reporting that John valued so highly.”

Acevedo will be honored at a luncheon in Miami in September.

About the award

The award — named after one of the most revered newspaper editors of his generation — is given annually to journalists who have contributed significantly to NLP and its mission. The honorees, who receive $500 and a glass plaque with an etched photo of Carroll, are selected by a committee of NLP board members and staff. During an acclaimed journalism career spanning four decades, Carroll was the editor of three major U.S. newspapers — the Lexington (Kentucky) Herald-Leader, The Baltimore Sun and the Los Angeles Times. He was a founding member of NLP’s board and served as its chair until shortly before his death in 2015.

Acevedo first became involved with the News Literacy Project in June 2017 as a moderator for a panel on news literacy and public libraries to mark the launch of NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom in the Miami-Dade Public Library System. A year later, he agreed to host the first Checkology lesson offered in English and Spanish — “Practicing Quality Journalism”/ “Practicando el periodismo de calidad,” a game-like simulation in which students assume the role of a rookie reporter covering a breaking news event. The lesson is one of the most popular on the platform.

He continued his work with NLP in April 2019, leading a session on identifying bias in news reports at a NewsLitCamp®hosted by Univision in Miami. He also follows and promotes NLP on social media.

“I’m thrilled to be part of NLP’s effort to reach Spanish-language audiences,” he said. “I can’t think of a better contribution to the future of journalism and the free press than our partnership with NLP. As journalists, we need to make sure everyone has access to these important tools.”

Notable career

Acevedo, who is also a special correspondent for the Fusion Media Group, has covered news around the world in Spanish and English for print, broadcast and digital media. Highlights of his work include his reports on the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, the AIDS epidemic in Africa, the humanitarian crisis in Haiti and the drug wars in Mexico.

He has interviewed a number of notable figures, including President Barack Obama, philanthropist Melinda Gates and Nobel laureates Bishop Desmond Tutu, Kofi Annan and Jody Williams. His Univision report “La Amazonía: Un Paraíso a La Venta” (“The Amazon: Paradise for Sale”) won an Emmy award for Outstanding Feature Story in Spanish in 2017.

Before joining Univision in 2012, Acevedo served as special correspondent and anchor for NBC-Telemundo and as a senior reporter for Televisa’s special investigations bureau in Mexico. In that role, he was the host of La Otra Agenda, a daily news program on ForoTV, Televisa’s 24-hour cable news channel, and a correspondent for the network’s investigative news magazine, Los Reporteros. He earlier was a national affairs reporter and special projects editor at Reforma, one of Mexico’s leading newspapers.

NLP working to counter the impacts of ‘Truth Decay’

A new report from the RAND Corporation, a nonpartisan nonprofit research organization, confirms what we at the News Literacy Project have long known: There’s an urgent need for media literacy education that is scalable, culturally relevant and readily available.

Released earlier this month, Exploring Media Literacy Education as a Tool for Mitigating Truth Decay was produced as part of a RAND initiative exploring “Truth Decay,” which it defines as “the diminishing role that facts, data and analysis play in political and civil discourse” — in part, because of an increasingly complex information ecosystem. This report aims “to describe the field of media literacy (ML) education and the ways in which ML education can counter Truth Decay by changing how participants consume, create, and share information.”

NLP’s expertise as a leader and pioneer in news literacy education is noted throughout the report, which weighs the input and suggestions of many experts in the field and lays out the challenges to developing meaningful education programs that can be scaled for significant impact.

Challenges and solutions

The RAND researchers describe the obstacles to buildi ng a news-literate population, such as the many skills needed to evaluate sources, to understand context, and to create and share information responsibly. They identify the alarming gap between proficiency in these skills and the abilities of average individuals: a gap that results in harmful consequences — vulnerability to disinformation, misinformation, viral hoaxes and bias.

ng a news-literate population, such as the many skills needed to evaluate sources, to understand context, and to create and share information responsibly. They identify the alarming gap between proficiency in these skills and the abilities of average individuals: a gap that results in harmful consequences — vulnerability to disinformation, misinformation, viral hoaxes and bias.

Our programs provide educators with the tools and resources that enable their students to close that gap and become civically engaged, news-literate adults. While the challenges detailed are real, I can say with confidence that NLP is successfully meeting many of them:

- The report describes the importance of scaling programs for significant impact. At NLP we have laid out a framework for scaling our e-learning platform, the Checkology® virtual classroom, with the goal of creating a community of 22,000 educators teaching 3 million students annually by 2022. Since its launch in 2016, more than 129,000 students have created individual accounts on our browser-based platform (this does not include the many students who have been taught in a one-to-many format), and more than 19,000 educators in all 50 states, four U.S. territories and 108 other countries have registered to use it.

- The report rightly states that for media literacy education to succeed, it must be rigorously nonideological. All of NLP’s programs, including Checkology, are scrupulously nonpartisan and represent a variety of perspectives.

- The report explores whether media literacy education should be a stand-alone offering or integrated across disciplines. Because media literacy is an essential life skill, we have designed our programs for cross-discipline learning and lasting impact. Our curriculum conforms to state standards across disciplines (such as English language arts and social studies) and is used by media, technology and science educators. The critical-thinking and analytical skills that students gain from news literacy education serve them well long after they leave the classroom.

- The report notes the need for more developed assessment and evaluation of media literacy programs. For years, we have used formal assessments of students’ competencies before and after they are exposed to our platform, along with self-reported student feedback, to evaluate and enhance our curriculum. The impact is evident in what we heard from students who completed Checkology lessons in the 2017-18 school year (the most recent data available): 93% are more confident in their ability to detect misinformation, 81% are more likely to become more civically engaged, and 80% are more likely to correct misinformation they see online.

- The report cites experts who emphasize that the most effective media literacy education strategies “are those that reach participants in a format and context with which they are familiar and comfortable.” We reach students where they live — on their devices. And the report indicates the need for context and flexibility. Checkology lessons can be taught in a sequential order, or educators can customize them to serve their students at different grade or skill levels and in a wide range of subject areas.

Working with diverse partners

The authors also stress partnering with media organizations to achieve scale. Right from the start, NLP has partnered with outlets such as The Wall Street Journal, NPR, The Washington Post, The Houston Chronicle and Univision.

We did this for years through our initial classroom program and have continued to do so through our NewsLitCamps®, which bring scores of educators into newsrooms for a day of engaging teacher-driven professional development. This fall, we will fully launch our Newsroom to Classroom program, which will bring journalist volunteers into schools around the country, either in person or remotely. Diverse and dynamic journalists and experts on the First Amendment and digital media guide students through our Checkology lessons as well.

I welcome the conversations, collaboration and increased awareness that RAND’s timely work will prompt and look forward to expanding NLP’s contribution to the growing field of news literacy education.

Mueller testimony shows urgent need for news literacy

Millions of Americans will be paying close attention on Wednesday when former special counsel Robert S. Mueller III testifies before two congressional committees about his investigation into Russia’s election interference in 2016 and possible obstruction of justice by President Donald J. Trump. While Democrats and Republicans will no doubt disagree over Mueller’s testimony, it highlights the importance of developing a bipartisan approach to the threat that such disinformation poses to our democracy.

Mueller’s 22-month probe, which culminated in a 448-page report released in April, included meticulous documentation of how Russia’s Internet Research Agency fabricated news reports, created hashtags for fake groups, used the fake groups to promote simultaneous rallies pitting opposing sides against each other, and posted inflammatory language on social media that spread like digital wildfires. On Facebook alone, content posted by the Internet Research Agency reached more than 126 million Americans — about half the voting-age population — between January 2015 and August 2017.

But Americans would have been less vulnerable to these attacks if we had been taught how to recognize the deceptive tactics that were being employed against us. An electorate trained in news literacy would have had the critical-thinking skills to see through this disinformation.

As we approach the 2020 presidential election, this issue could not be more urgent. Last year, using data provided by Twitter, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology reported that a false news story was 70% more likely to be retweeted than one that was true. They also discovered that while true stories rarely reached more than 1,000 people, the top 1% of false stories were routinely spread by between 1,000 and 100,000.

Even digital natives, like today’s students, are vulnerable: A 2016 study by the Stanford History Education Group found that 80% of middle school students believed that “sponsored content” ads were real news reports, while fewer than 20% of high school students questioned the credibility of a misleading photo. If we don’t take steps to rectify this situation now, we’re potentially dooming our digitally focused future generations to a lifetime of struggling to separate fact from fiction.

To give young people the tools they need to be informed participants in the life of their communities, it’s not necessary to reinvent the wheel. Think of it as an updated version of civics education, one that helps students inoculate themselves from the pandemic of misinformation — whether from trolls, profiteers or adversarial governments — that infects our public discourse.

Lawmakers in a number of states have responded to this moment by introducing or enacting legislation that would support the adoption of media literacy education in public schools. Civics courses, which often include a media literacy component, are returning as a high school graduation requirement; in Illinois, which has such a requirement, a bill that would also mandate civics education in middle schools awaits the governor’s signature.

The News Literacy Project, which I founded 11 years ago and continue to lead, has developed curriculum, resources and programs that give educators the tools to teach middle school and high school students how to determine what is real and verified versus what is false and manipulated. We’ve seen how building news literacy skills helps students become critical thinkers. They learn to approach information with equanimity, not emotion; to value credibility, not clickability. They emerge more confident in their ability to discern and create truthful information and more likely to correct errors when they find them. This deliberative mindset will serve them well through a lifetime of informed decision-making and civic engagement. They are now part of the information solution, not part of the misinformation problem.

I’ll leave it to the politicians to determine their response to Mueller’s testimony. But I hope we all can unite around the idea of empowering teachers to educate young people to become savvy enough to spot any misinformation or disinformation that comes their way. A news-literate public will be cognizant of the challenging information landscape and know how to confidently blaze a trail through the confusion and distortion for others to follow.

‘The Eagle has landed.’ Really.

While it’s an exaggeration to say that the whole world was watching when Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first person to walk on the moon on July 20 fifty years ago, this history-defining moment truly riveted people around the globe.

NASA estimates that 650 million people — almost 20% of the global population in 1969 — tuned in when Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin touched down on the moon’s surface aboard the lunar module Eagle on July 20, 1969.

But the astronauts had barely planted an American flag on the moon’s dusty surface when conspiracy theorists began claiming that the mission was staged. Even overwhelming evidence to the contrary could not dissuade those who believed that the moon landing was an elaborate government hoax. The same is true of people who cling to any number of conspiracy theories today.

Their persistence and appeal

While it may seem easy to dismiss such outlandish beliefs, conspiracy theories can lure us in by turning healthy skepticism into damaging cynicism. In an interview with The Verge, Mike Wood, who teaches psychology at the University of Winchester, suggests that we’re especially vulnerable in certain circumstances. These include when we’re repeatedly exposed to such information, when we’re experiencing significant stress or when a particular theory resonates with our values. Once conspiratorial thinking takes hold, it can spread, leading us to embrace even more dangerous falsehoods.

Don’t be lured in

Milestones, such as the moon landing anniversary, rightly draw legitimate news coverage. However, that coverage can also revive conspiracy theories. Today and every day, be sure to seek out credible sources online, question your assumptions, and recognize when you might be vulnerable to information you would otherwise view with skepticism. And help your family and friends to do the same.

With the help of all of our supporters and friends, NLP is working to empower young people to recognize conspiracy theories — and other misinformation — for what they are.

Photo: Apollo 11 astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin stands beside the United States flag planted on the moon’s surface. Photo credit: NASA.

Starting off our new year with momentum

Although the calendar and the thermometer tell us that it’s summer, it’s a new year at NLP. To better align with the teaching and learning schedules of the educators and students we serve, NLP kicks off its new year in July — not with corks popping or a ball dropping, but with a staff retreat.

We came together last week in Washington for four days of collaboration and camaraderie that celebrated how far we have come and charted where we are going.

On the first day of the retreat, July 8, we welcomed four staff members, including three in newly created positions. They, along with seven others who joined NLP in the past year, are key to achieving our objective of bringing news literacy education to 3 million students annually by 2022.

We also recognized the contributions of Peter Adams, our senior vice president of education, who joined us a decade ago. Peter’s vision, commitment and expertise have been at the heart of what we do. He has been instrumental in the development, refinement and expansion of the Checkology® virtual classroom, the creation and success of our NewsLitCamp® professional development events, and the conception and execution of The Sift®, our weekly newsletter for educators and others interested in news literacy.

Whether veteran or newbie, every staff member at NLP is committed to the vision of embedding news literacy in the American education experience. In the next few months, we will unveil new tools and programs and resources that will help achieve that vision.

But for now, let me introduce you to the newest members of the NLP family:

Mike Webb, senior vice president of communications, joins NLP after serving as a vice president at the Washington public affairs firm BerlinRosen, where he led client teams on youth advocacy issues. Earlier in his career, Mike was the first communications professional hired by ProPublica, the Pulitzer Prize-winning nonprofit news organization, and spent five years there as director and vice president of communications.

Henok Tedla, NLP’s first finance director, has more than a decade of experience with nonprofit organizations. A certified public accountant, he comes to NLP from the Global Business Travel Association, where he was director of accounting.

Alicia Trader is the educator services team’s first service support associate. She previously was the marketing department coordinator at Perma-Bound Books, one of the largest educational resource organizations in the country.

Sara Lewis is NLP’s first office manager, assisting the staff in our Washington headquarters. She has experience as a teacher and nonprofit professional working with students in under-resourced communities.

Photo: The News Literacy Project staff at our annual retreat dinner. Photo credit: Molly Hill Patten for the News Literacy Project.

Even nation’s founders considered impact of misinformation on democracy

How are you celebrating the Fourth of July — with fireworks, a parade, a family cookout?

May we suggest sharpening your news literacy skills? Our nation’s founders would be proud of you.

While they didn’t have to contend with the 24-hour news cycle, internet trolls or disinformation-spewing bots, the Founding Fathers were concerned that misinformation could weaken their young democracy.

As Tim Libretti, a professor of U.S. literature and culture at Northeastern Illinois University, wrote last month on PoliticusUSA.com, the founders were worried about meddling by foreign powers. They also worried about the vulnerability of the population to deceit and manipulation by their fellow citizens.

America was piloting a new form of government. It was a concept based on government of the people, by the people and for the people, as Abraham Lincoln would describe it almost 75 years later. And the Founding Fathers were putting a lot of stock in the people’s ability to make sound decisions based on factual information that served the public good.

Trusting in education

John Adams had his doubts, Libretti noted. He feared that “human reason, and human conscience, … are not a match for human passions, human imaginations, and human enthusiasm.” Thomas Jefferson put his faith in the power of education.

At NLP, we put our trust, resources and hard work into the conviction that education is the most effective approach to developing a news-literate public. Our society relies on people who can think critically, engage responsibly with information, value our democracy and participate in keeping it robust.

Thanks to your support, we are working to bring news literacy education to many thousands of young people in classrooms across the nation.

In turn, these informed consumers and creators of news and other information can impart their skills to the adults in their lives.

NLP’s Newsroom to Classroom program brings journalist visits back to schools

Journalist and Columbia University professor emerita Ann Cooper (center, on screen) “visited” a fourth-grade class at Carl Von Linné School in Chicago June 20 and spoke to students about journalism and the role of a free press in democracy. Photo credit: Jodi Mahoney.

Usually, the last day of school is an exercise in the mundane: emptying lockers, clearing out desks, shelving books in the library. But that wasn’t the case on June 20 for the fourth-graders in Jodi Mahoney’s technology classroom at Carl Von Linné School in Chicago.

They wrapped up the school year with a virtual visit from Ann Cooper, an award-winning radio and print journalist and the CBS Professor Emerita of Professional Practice at Columbia Journalism School in New York City. The topics of the day: why freedom of the press is important, what reporters’ jobs entail and how the students would cover a story about bullying.

Cooper’s visit with Mahoney’s class was the first in NLP’s new Newsroom to Classroom program — a revival of the journalist visits that were a hallmark of our initial classroom and after-school programs in New York City, Chicago, the Washington, D.C., area and Houston. Through this initiative, educators with Premium access to our Checkology® virtual classroom can invite NLP journalist volunteers to visit their classrooms, in person or virtually, and give students the benefit of their experience and expertise.

Based on what Mahoney and Cooper told us, the visit was a success.

‘Students loved it’

“Ann talked to students about how news and access to news has changed, what journalists do, discussed freedom of the press internationally and in the U.S., and had students discuss a real-life example of a student who was bullied on a bus and how they would handle it if they were reporters on their school newspaper,” Mahoney said. “Students loved it.”

Cooper also noted how that real-life example resonated with the class. “To my surprise, many students jumped right in with ideas and questions,” she said.

To ensure that the visit would be meaningful, Mahoney and Cooper discussed topics in advance. They decided to tie the session to the Checkology lesson “InfoZones,” in which students learn to identify the primary purpose of information. Cooper also provided the students’ homeroom teacher with materials for them to review.

During the visit, Cooper described her experiences as a journalist (she was, among other things, NPR’s first Moscow bureau chief), explained why journalism is important to society and spoke to the class about how some governments and lawmakers seek to curb press freedom.

“We specifically talked about the case of Ivan Golunov of Russia, which played out over the previous week,” she said. (Golunov, who has exposed corruption in Moscow for the news website Meduza, had been arrested and held under house arrest for attempting to sell drugs, a charge his supporters said was fabricated; he was released when authorities said there wasn’t evidence to hold him.) “They had watched some videos about the case as it unfolded, and they had good questions and observations.”

‘Valuable learning experience’

At the end of class, Cooper asked the students if they would be interested in becoming journalists. “The entire class enthusiastically raised their hands and shouted ‘Yes!’” Mahoney said. “This was a valuable learning experience for my students.”

Mahoney and Cooper have agreed to schedule a second visit with the same students in the fall.

I was delighted to hear that this initial session went so well and look forward to hearing about many more significant classroom connections in the 2019–20 school year. The Newsroom to Classroom program is just one way that NLP is greatly expanding its reach and impact and enhancing the experience of both educators and students.

So far, volunteers include journalists from such outlets as The New York Times, NPR, The Washington Post, Univision, The Wall Street Journal, ProPublica and WBEZ, Chicago’s public radio station. Journalists interested in participating in Newsroom to Classroom can learn more by emailing [email protected].

A proposal to honor journalists who died doing their jobs

One year ago today, a gunman opened fire in the newsroom of the Capital Gazette in Annapolis, Maryland. The attack took the lives of five people, four of them journalists, on the deadliest day for American journalism in modern history.

With that tragedy in mind, legislation introduced in Congress this week deserves everyone’s support. The Fallen Journalists Memorial Act of 2019 (H.R. 3465 in the House, S. 1969 in the Senate) would authorize the Fallen Journalists Memorial Foundation to raise funds and work to locate and erect a memorial on federal land in Washington to pay tribute to journalists who have died while doing their jobs — including those slain in Annapolis.

This legislation stands apart in this climate of political division and partisan rancor because it has bipartisan sponsorship in both the House and the Senate. And it comes at a time when public officials and others irresponsibly label reporters as “enemies of the people” and decry information unfavorable to them or their cause as “fake news.”

David Dreier, the chairman of the Capital Gazette’s parent company, Tribune Publishing, and a former Republican member of Congress, leads the foundation, which operates under the auspices of the National Press Club Journalism Institute, the press club’s nonprofit affiliate.

The memorial, to be funded solely by money raised privately, would honor fallen journalists from around the world as limits on press freedom and attacks on journalists escalate. Reporters Without Borders’ 2019 World Press Freedom Index noted that threats against reporters are mounting worldwide, with just 24% of countries rated as having a “good” or “satisfactory” climate for the practice of journalism.

At NLP, we value the role of a free press and the practice of responsible journalism. Lessons in our Checkology® virtual classroom help young people understand and appreciate the vital role of a free press in a healthy democracy. Students also gain an understanding of the First Amendment, explore how press freedoms differ around the world, and learn and practice the standards of quality journalism.

Every day, journalists risk their lives to report the news so the public can make informed decisions about their world. Sometimes that work proves to be deadly. This memorial would honor those individuals — from Ernie Pyle to Marie Colvin to Jamal Khashoggi — while also recognizing the incalculable worth of a free press to a healthy democracy.

Checkology changes how student engages with the world

Diego Hernandez, who recently completed ninth grade at Daniel Pearl Magnet High School in Van Nuys, California, believes misinformation can harm your outlook on the world.

But Checkology® virtual classroom, which he used in his journalism class, has changed how Diego approaches news and other information. “Now I’m thinking on both sides of the spectrum,” he says. “It just gives you a whole new way of thinking about certain things.”

The platform also has taught him to take a step back and evaluate information more critically. He has become aware of bias in the information he consumes and seeks out information that is fact-based rather than opinion-based.

“I’ve changed a bit as a person. My opinions have altered a bit,” Diego says.

Learn more about how Checkology has impacted Diego in this video.

Christina Van Tassell and Molly Hill Patten join NLP board

Christina Van Tassell, the chief financial officer at Dow Jones, and Molly Hill Patten, chief operating officer at Ideas42, a nonprofit that applies behavioral science to complex problems around the world, are the two newest members of the News Literacy Project’s board.

“Molly and Christina bring impressive financial experience and acumen to the NLP board, as well as a strong commitment to the mission of news literacy,” said NLP board chair Greg McCaffery. “Their participation is particularly welcome given the dramatic recent growth of our budget and staff as the organization moves to the next level in creating a news-literate next generation.”

Before being named CFO at Dow Jones — publisher of The Wall Street Journal and Barron’s — in 2017, Van Tassell (pictured left) was global CFO at Xaxis, a digital media company, and a partner and CFO at Centurion Holdings, a consulting and investment firm. She began her career in finance at Coopers & Lybrand (now PricewaterhouseCoopers), working in New York City, the United Kingdom and Sweden. She is also a member of the board of directors of Unruly, a video marketplace owned by News Corp.

“I am honored to join the News Literacy Project Board,” Van Tassell said. “The NLP marries two of my passions — young people’s education and the importance of trusted journalism. I am excited to participate in the advancement of this great cause.”

Patten (pictured right) joined Ideas42 in 2018 from Aledade, a health tech start-up, where she was senior vice president of finance and operations. She has an extensive background in finance and business, including at Revolution LLC, where she was vice president of finance; Exclusive Resorts, where she was vice president for financial and strategic planning; and AOL, where she was director of broadband. She was named Financial Executive of the Year by the Maryland Tech Council in 2017.

“Education and a free press are two of the most important institutions of American life,” Patten said. “As Thomas Jefferson said, ‘They are the only sure reliance for the preservation of our liberty.’ I’m very pleased to join the board of the News Literacy Project, a nonpartisan national education nonprofit that supports both institutions.”

Venezuelan reporter brings unique perspective to NLP

For Univision reporter Maria Alesia Sosa, the recent news that press freedom in the United States was now considered “problematic” by an international media watchdog group wasn’t as daunting as it might be to other U.S. reporters.

It’s not that she isn’t concerned about the trend — but she is from Venezuela, which is ranked 148th (the U.S. is 48th) out of 180 countries and regions on the Reporters Without Borders 2019 World Press Freedom Index. And that perspective means a lot to Sosa, who led a session on local journalism at the News Literacy Project’s NewsLitCamp® in Miami in April and is appearing in a video about the state of journalism in her home country for the “Press Freedoms Around the World” lesson on NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom.

“Venezuela right now, we are under a dictatorship and there is zero freedom of the press,” said Sosa, who spent eight years as a reporter there before moving to Miami in 2016. “If you are against the government or if the government knows that you are against them, you will be chased, you will be attacked, you will be followed for your thoughts and for what you write.

“What I’ve really appreciated here is the freedom that I have to write, to do stories, and to report on whatever subject I want.”

Difficult, dangerous work

In Venezuela, mainstream media is dominated by government-owned newspapers and television stations. Reporters who are “driven by truth, and not by politics,” publish their work online to ensure that it will be seen, Sosa said. Reporting is difficult and can be dangerous; for example, Sosa said, when she tried to speak to shoppers in a grocery store about the scarcity of food, she was harassed and chased by the military. She said she could never get a complete answer — or access to what should have been public information — from government officials.

“In Venezuela you are not able to get data,” she said. “There’s no public data.”

By contrast, Sosa said of her work at Univision, “there hasn’t been a story that my boss tells me, ‘Don’t do this, don’t report it.’”

Earlier this year, Sosa and a colleague reported on the deaths of patients who underwent a popular, but often dangerous, type of plastic surgery at “cosmetic centers” in south Florida — facilities that the state Department of Health had no authority to regulate because they were not owned by physicians. As a result of their reporting, and that of other news organizations, the state legislature recently passed a bill, now awaiting the governor’s signature, that would, among other things, allow the state to suspend the operation of these centers, or shut them down entirely, if they were found to pose an “imminent threat” to the public.

“Actually, we changed the law,” Sosa said, calling the end result “surreal.”

“That’s the real sense of journalism, the real watchdog sense of journalism,” she added — something that she said “is impossible in my country. That won’t happen until we have fair institutions in my country.”

Sosa returned to Venezuela in 2017 to report on the ongoing protests against the government of President Nicolás Maduro — a trip where she said her life was in danger.

“That time was one of the most terrible attacks that I suffered,” she said. “Pro-government groups and thugs attacked me and my partner who was working with me. They attacked us with a knife.”

An urgent need

Sosa has great admiration for her former colleagues and other reporters who are still in Venezuela. She also is aware, from experience, how frustrating their work is because of the utter lack of press freedom.

“Their great jobs, their words have no effect,” she said. “I’m sure they will have someday. They win prizes and everything, but the best prize for this is when we change something.”

Reflecting on the climate in the United States, the spread of terms like “fake news,” and the public’s declining trust in media, Sosa understands the urgency of the News Literacy Project’s work. Journalists are “voices for the voiceless,” she said. “But if people don’t watch or don’t read us, we are no one.”

She was emboldened by the NewsLitCamp in Miami, which underscored for her the importance of journalists speaking to groups, such as educators, about their work so the public will understand and trust it.

“We have to open our minds and just tell more people how our jobs are done, how we do our work, how we corroborate,” she said.

She believes that if journalists stick to the facts and give readers and viewers a better understanding of how and why reporting is done — lessons learned throughout Checkology — then trust in journalism can be restored.

“To tell the world how important the facts are — that’s the only way that we reduce bias,” Sosa said.

Photo caption: Maria Alesia Sosa visited a U.S. Coast Guard site in March to report for Univision on the seizure of more than 27,000 pounds of cocaine (in black plastic bags). Photo courtesy Maria Alesia Sosa.

Checkology student wants to set a good example for her sister

Valeria Luquin, a ninth-grader at Daniel Pearl Magnet High School in Van Nuys, California, is one of the thousands of students who have benefited from the News Literacy Project’s Checkology® virtual classroom.

She said it has helped her to become more aware of the news and other information she encounters every day. “I feel like I’ve gotten better at being a journalism student and identifying real news from fake news,” she told us.

She has also brought her news literacy skills home to her family. As an example, she said, she asked her father about the credibility of the sources in a documentary he had watched. “He looked at me and told me, ‘I notice that you’ve gotten a lot more critical,’” she said, adding: “That made me realize I do act more critical.”

And, she noted, “it’s important that I’m a good role model” for her 7-year-old sister: “It’s important for us to be critical, especially because we’re the next generation in the world.”

See more of Luquin’s story below.

Education can solve ‘dueling facts’ phenomenon

The conclusions that political scientists Morgan Marietta and David C. Barker reach in their new book, One Nation, Two Realities: Dueling Facts in American Democracy, are enough to make the reader despair.

Based on data from national surveys conducted from 2013 to 2017, they determined that “dueling fact perceptions are rampant, and they are more entrenched than most people realize.”

In an article published May 8 on the NiemanLab website, the authors noted that, according to their findings, Americans no longer agree on basic questions of fact and often cling to beliefs that align with their values, regardless of evidence to the contrary. And fact-checking by reliable organizations appears to have little success in correcting people’s erroneous views. “This has serious implications for American democracy,” they warned.

I couldn’t agree more.

However, I think that Marietta and Barker are mistaken in their bleak prognosis: “Perhaps the most disappointing finding from our studies — at least from our point of view — is that there are no known fixes to this problem.”

The fix

There is no denying that today’s complex information ecosystem challenges all of us, but I believe that there is a fix to the problem: news literacy education. News literacy must be embedded in the American education experience. Nothing less than the health of our democracy is at stake.

As the founder of the pioneering News Literacy Project, I have seen how real-world news literacy lessons can empower middle school and high school students. The Checkology® virtual classroom, our e-learning platform, reaches them as they are forming the habits of mind and the patterns of content consumption and creation that will last a lifetime, and it does so where they live — online.

The value of these newfound and lasting news literacy skills has resonated with Judy Bryson, a library media teacher at Wilmer Amina Carter High School in Rialto, California. “If students are going to advocate for themselves and become empowered citizens, they need to know where to find quality, trustworthy information,” she said, adding that Checkology has helped her integrate library and research skills into a variety of subjects.

Meaningful engagement

The platform’s relatable examples engage students in meaningful ways. They begin by learning to identify types of information based on its primary purpose (to inform, to entertain, to persuade, to provoke, to sell or to document) and then review examples of content and assign them to the correct categories.

In another lesson, students take on the role of a reporter covering a breaking news story. They learn the importance of evaluating sources, weighing witness accounts, paying attention to attribution and recognizing how the standards of quality journalism come into play. Other lessons explore how to assess the authenticity of photos and videos and determine the credibility of memes and viral hoaxes.

In short, students learn to think like journalists: After all, in the digital age, anyone can be a publisher, and everyone must be an editor.

Critical thinkers

Checkology doesn’t just impart specific news literacy skills; it helps students become critical thinkers. They learn to approach information with equanimity, not emotion; to value credibility, not clickability. This deliberative mindset will serve them well through a lifetime of informed decision-making.

Educators see how transformative this can be in their classrooms — and beyond.

Nicole Finnesand, a middle school language arts teacher in Colton, South Dakota, said that Checkology has provided a framework for her deeply polarized class to have constructive and civil discussions about current events and political issues. Students now come to class armed not just with opinions, but with facts and legitimate sources. (As an example, they no longer cite The Onion’s satire as the basis for their arguments.)

David Teeghman, who spent several years teaching at a Chicago high school, said the platform helped him inoculate his digital journalism students against conspiracy theories and manipulated or fabricated content. He recalled seeing one of his former students post a falsehood on Facebook. Before Teeghman could respond, other former students jumped in to respectfully call it out.

Empowered students

Students immediately begin to apply these lessons in the real world.

Valeria Luquin, a ninth-grade student at Daniel Pearl Magnet High School in Lake Balboa, California, said that her father had recently told her about a documentary he had watched. “Are you sure that the sources and the documentary are credible?” she asked him. She said the ability to think critically about the media “is really helpful and important, because nowadays, with social media, there can be a lot of fake news.”

Sophia Fiallo, now a 10th-grader at The Young Women’s Leadership School of Queens in New York City, said her news literacy skills kicked in last year when a friend shared a photo of Emma Gonzalez, a student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, tearing up the U.S. Constitution. Fiallo discovered that it was a doctored photo of Gonzalez ripping a shooting target as a protest against gun violence. “It didn’t come from a reliable news source,” Fiallo said.

Ultimately, we want students to recognize that they can be part of the information solution, rather than part of the misinformation problem.

Daniela Rangel, one of Luquin’s classmates at Daniel Pearl Magnet High School, exemplifies this goal. “I like to help people in whatever way I can,” she said. “So if that means telling them that they should try to find correct information over what they are seeing on social media, then that’s good.”

Besides, she added, “I think my parents take me a little bit more seriously. Why? Because I’m more literate, and I sound professional now.”

Improving science education through news literacy

You won’t always see Kelly Melendez Loaiza’s students using beakers and Bunsen burners to demonstrate their grasp of the scientific method. That’s because this science teacher brings the rigors of evidence-based inquiry out of the lab and onto the laptop.

“Facts must be supported by reliable sources. They are not feelings or hunches,” Melendez Loaiza recently reminded students.