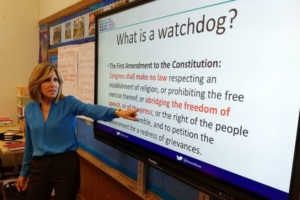

NLP board member Liz Ramos wins California teaching award

NLP is thrilled to offer heartiest congratulations to Liz Ramos, a high school teacher and a member of our board of directors, on being named Outstanding Secondary Level Social Studies Teacher of the Year by the California Council for the Social Studies (CCSS).

NLP is thrilled to offer heartiest congratulations to Liz Ramos, a high school teacher and a member of our board of directors, on being named Outstanding Secondary Level Social Studies Teacher of the Year by the California Council for the Social Studies (CCSS).

The Constitutional Rights Foundation of Los Angeles nominated Liz for the award, which recognizes educators whose classroom teachings and professional practices reflect the goals and purposes of an exemplary social studies education.

Liz told NLP that she was honored to receive the award, adding: “I strive to create a classroom and lessons that engage students, open the world up to them, and help them to become informed and engaged citizens. This is such an amazing time to be teaching with technology and resources that allow teachers to take the students beyond the classroom walls.”

She has taught history and U.S. government at Alta Loma High School in Rancho Cucamonga, California, since 2005. She actively integrates technology into her curriculum, emphasizing media and digital literacy, to help her students to seek information and to demonstrate what they have learned.

Liz began using NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom within weeks of its release in May 2016, first with students in summer school and then with her college prep and AP government classes in the fall. The platform, she says, has helped give all of her students “the tools to evaluate credible takes on a story, examine and understand the various purposes of news and media, and to be aware of bias and deceit by providing a framework to question the news and social media postings and be critical thinkers for reference in life moving forward.”

She was a member of NLP’s strategic plan steering committee and joined the NLP board in 2017. She has attended our NewsLitCamp® professional development events in Los Angeles and Chicago and led a workshop that featured Checkology (“Empowering Students to Navigate Today’s Challenging Media Landscape”) at the National Council for the Social Studies’ annual conference in 2017.

Liz and the other award winners will be honored on March 15 at an event during the CCSS annual conference in San Jose.

What is engagement bait?

In a previous post I described how debunking misinformation is a meaningful civic action. When we discuss misinformation, we often focus on the types that elicit strong emotional responses and are trying to influence political, social or cultural views. There is another common type of misinformation that we should be paying closer attention to: It’s called “engagement bait,” and, as the name implies, we engage with it often.

Engagement bait is a type of social media post that is designed to get you to interact with (seemingly) innocuous content through likes, follows, shares and comments. These posts are often created by accounts that have two specific goals in mind: First, build a large following for the account; then, monetize that following.

Here’s one example:

In this image, photo editing software was used to add the weapons. A reverse image search brings up several variations of the picture, along with a link to a Corgi owners discussion forum where the person who took the original photo talks about how it went viral.

As an account like this one accumulates followers, increases engagement and becomes more popular, the owner can use a service such as PaidPerTweet or SponsoredTweets to monetize its following through advertising. Eventually the owner can sell the account — and all of the followers it built up.

At this point you might be asking, “So what? Why should we care about fluff items about cute animals?” After all, these manipulated images of animals or nature scenes seem harmless enough. Social media platforms routinely serve us ads anyway, so we probably don’t notice.

But beware: Some engagement bait posts can leave you vulnerable to identity theft.

Many of us have been tagged by friends to answer questions about ourselves: What was the first concert you went to? What color was your first car? “Tag baiting” is another type of engagement bait, and it counts on you and your friends tagging each other, either in the comments of a post or in a post you share on your timeline, so that the post spreads from friend to friend.

What you may not realize while sharing fun facts about yourself is that many of these seemingly innocent questions are remarkably similar to security questions for online banking and other secure accounts. If you get enough people to respond and share, you have a gold mine of personal information.

In December 2017, Facebook announced that it was taking steps to address five specific types of engagement bait:

- Vote baiting: These often take advantage of Facebook’s reactions. Users will see two options (such as images) and are asked to “like for option 1, love for option 2.” The more people “vote,” the more popular the post appears, making it appear in more timelines. On Twitter this would be “like for option 1, retweet for option 2.”

- React baiting: This is similar to vote baiting, but usually only involves one example in the post.

- Share baiting: A post appears in your feed, asking you to “share” or “retweet” if you like it or agree with it. The more the post is shared or retweeted, the more popular it appears.

- Tag baiting: As noted above, a post asks you to tag a friend in the comments or share the post to your friend’s page. That makes the post appear in your friend’s news feed, where it encourages your friend to tag their friends. The more people get tagged, the more popular the post appears. (Seeing a pattern?)

- Comment baiting: A post asks you to write specific words or phrases in the comments section. As more people comment, the post appears to be more popular.

These types of posts try to leverage Facebook’s news feed algorithms to boost both more typical engagement bait posts (adorable animals, “amazing” nature photos, etc.) and posts for companies, products or services — often for unethical and sometimes illegal purposes. The same is true for Twitter and Instagram, though the engagement obviously varies by platform.

(Since that announcement, Facebook has expanded the demotion of “engagement bait” posts to include those written in 22 languages other than English. The company also is demoting comments that contain engagement bait, meaning that those comments are less likely to appear in users’ timelines.)

Sometimes, the engagement bait is being used to promote a legitimate business or a cause — a form of viral social media marketing. Here’s an example from the DC Extended Universe, promoting the movie Aquaman:

This post is designed to encourage people to follow the DCEU account and generate popularity through retweets — meaning the company doesn’t have to pay for it to be a promoted post on Twitter. Marketing efforts like this are common, but they’re still engagement bait.

Compare the DCEU promotion with this, however:

Several fake Lululemon accounts on Instagram posted an image advertising a fake brand ambassador program. This used a combination of engagement bait tactics, and it was widely shared by thousands of users. (In fact, Lululemon does have an ambassador program, but it is managed through individual stores — not online.) While the account that posted the original hoax no longer exists, the image it created continued to spread. (And the date can be manipulated, so this falsehood could continue into this year and beyond.)

Other social media platforms are also attempting to mitigate engagement bait. Last month, Twitter suspended the @oldpicsarchive account, which routinely posted images that were manipulated, were posted in false context or were complete fabrications. Such posts are debunked daily by accounts — such as @HoaxEye and @PicPedant— that follow engagement bait accounts and use digital forensics skills to debunk false images, hoaxes and other misinformation.

Understanding the difference among the various types of engagement bait is just as important as knowing how to identify news, opinion, propaganda, advertising, entertainment and raw information. It applies the same analysis skills to determine what is true and what is false. The Aquaman post is real, and that can be verified. The Lululemon post is not real, and that can also be verified. Many other forms of engagement bait use manipulated or fabricated images and other forms of misinformation to generate likes, shares and follows; these can also be verified using digital forensics and fact-checking skills.

With most forms of engagement bait, if it looks too good to be true, it probably is — so don’t like, share, follow, retweet or comment on it!

NLP’s Adams looks at migration in the context of news literacy

Messages and images that appear online, in print and on television strongly influence how people think about issues such as migration, according to Peter Adams, NLP’s senior vice president of education.

“People see different things in the way stories are reported, or in photos that are used to represent a situation or person,” Adams told Adam Strom of UCLA’s Re-imagining Migration project, noting that the way a group of migrants is identified in the media — as “an army” or as “a pilgrimage,” for example — can affect a reader’s or viewer’s perception. “If a piece of information causes you to have a strong emotional reaction, you need to be careful — because when our emotions are high, they can override our rational minds and cause us to miss key details.”

Chicago students tackle what’s real and what’s fake

When David Teeghman, a teacher at Michele Clark Academic Prep Magnet High School in Chicago, first heard about the Checkology® virtual classroom, it was a no-brainer: “I was like, ‘YES, this is a resource that my students need to have access to.’”

Navigating the information landscape these days is difficult enough for adults — and even more challenging for his students, many of whom had never seen The New York Times or The Washington Post and didn’t know the difference between an unreliable source and a credible one.

“These skills were missing in my students,” Teeghman said. “They would be susceptible to conspiracy theories, they couldn’t differentiate a real from a fake piece of content, they couldn’t tell when something had been manipulated or put in the wrong context — or had just been fabricated entirely.”

In the three years since he introduced Checkology in his classroom, Teeghman has noticed consistent improvement in his students’ ability to trust what he calls their “spidey sense” — the feeling that something isn’t right — and find the facts.

“The biggest challenge as a teenager about getting information is knowing if it’s real or not,” said Nayaisha Edmond, a student in Teeghman’s digital journalism class. “I improve day by day as I get on Checkology.”

Teeghman, too, has only praise for the platform: “I love how decentralized it is, I love how individualized it is, and I love that students can work at their own pace.” He is also impressed by the diversity of representation in the lessons. His students, he said, “can see themselves in the videos.”

But what’s most important to this educator is that his students take their newly acquired news literacy skills out into the real world, and that after they leave his classroom, they continue to apply what they have learned. Much to his delight, they do.

Once his students have finished his class, he said, he allows them to “friend” him on Facebook. One day, he noticed that a former student “unfortunately” posted something false on his feed —and he was gratified to see that other former students — in an online conversation he described as “very respectful” yet ”spirited” — “jumped in to correct that before I even had a chance to say anything!”

Watch this video from our visit to his classroom.

NLP students join Broadway stars to consider ‘true’ versus ‘true-ish’

NLP’s Alan Miller (left) moderated the talkback session with Lifespan of a Fact director Leigh Silverman and actors Bobby Cannavale, Daniel Radcliffe and Cherry Jones. Photo by Miriam Romais/The News Literacy Project

“Facts have to be the final measure of truth.”

That’s what fact-checker Jim Fingal (portrayed by Daniel Radcliffe) says in the play The Lifespan of a Fact. At the News Literacy Project, we believe that the lifespan of a fact is eternal.

The play, based on a 2012 book by Fingal and writer John D’Agata (played by Bobby Cannavale) about Fingal’s fact check of an essay by D’Agata, shone a light on the tension between accuracy and creative license. And on Tuesday, students from two New York schools that use NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom — the Young Women’s Leadership School of Astoria and the Bronx Collaborative High School — attended the play and participated in a talkback session with Radcliffe, Cannavale, Cherry Jones (who plays Fingal’s boss, a magazine editor), and the play’s director, Leigh Silverman. NLP founder and CEO Alan Miller moderated the discussion.

The 30-minute Q&A covered a number of topics, such as the importance of the arts and the ability to enjoy a movie “based on a true story” without looking up every fact upon leaving the theater. The actors also had a strong message for the students, describing how their roles in the play had strengthened their respect for journalism and for real-life fact-checkers. In fact, in preparation for this part, Radcliffe shadowed a fact-checker at The New Yorker.

“It gave me incredible faith,” Radcliffe said, noting that he was “inspired” by the “people out there who are doing this job and doing it amazingly rigorously.”

Checkology students Christina Wright (left) and Kelis Williams from Bronx Collaborative High School. Photo by Miriam Romais/The News Literacy Project

The play, in a limited run at Studio 54 in New York City, centers on Fingal’s fact check of an essay by D’Agata before it is published in a magazine. It devolves into a philosophical argument over “true” versus “true-ish”: Fingal and D’Agata disagree, for example, over whether specific numbers — how many strip clubs there are in Las Vegas, for example — must always be accurate (the fact-checker’s opinion) or can be changed to serve a literary purpose (the essayist’s opinion). The audience applauded when Fingal described facts as “the final measure of truth.”

All three actors responded to the students’ questions with answers that led to a similar conclusion: A play might not be based on facts, but the news you consume every day needs to be. Every time.

“It’s just the world we’re living in now, isn’t it, where every day people in power play fast and loose with the facts,” said Jones, adding that it’s only because of “superb journalism” that their misstatements are known.

The night ended with a group photo — and NLP bumper stickers (“My facts just ran over your fiction”) for the actors and the director as a reminder to continue to fight for facts. The students thanked Radcliffe, Cannavale, Jones and Silverman for the opportunity. Amazingly, no one asked Radcliffe anything about Harry Potter.

And that’s a fact.

To track local news coverage, curate a list of local journalists

ProPublica Illinois (@ProPublicaIL) regularly uses Twitter to answer questions about journalism. Recently a reader asked: “How do you go about finding those new ideas? Is it by brainstorming? Or following on tips?”

Here’s the response from ProPublica journalist Jodi Cohen:

“Reporters are always on the lookout for ways to inform the public about the world we live in, including wrongdoing. We go to all kinds of public meetings — for school boards, city councils and park districts — and not only report the daily news but look for the bigger stories by spotting trends, questionable spending and more. We ask a LOT of questions.”

So who’s going to these meetings and asking the questions in your community? As part of a project to track local news coverage and encourage students to contact and interact with journalists, consider curating a list of local journalists. Most journalists routinely use Twitter for their work. If you have a Twitter account you use for your classes, here’s how to create a Twitter list:

- Click on your profile icon. (On a computer, the profile icon is in the upper right corner of the screen between the search box and “Tweet”; on mobile devices, it’s in the upper left corner.)

- Click on “Lists.”

- Click “Create new list.”

- Select a name for your list and give it a short description. List names cannot exceed 25 characters or begin with a number. Decide if you want the list to be private (only you can see it) or public (anyone can subscribe to it).

- Click “Save list.”

Next, add the Twitter accounts of local journalists to your list:

- Once you’ve identified an account that you want to add to your list, click the overflow icon on the journalist’s profile page (on a computer, the three vertical dots next to the Follow/Following button; on mobile devices it may be the same three vertical dots and others the gear).

- Select “Add or remove from lists.” You don’t need follow an account to add it to your list.

- A pop-up will appear with the lists you have created. If you’d like to add the journalist to a list, click the checkbox next to the list name. To remove an account from a list, simply uncheck the box.

- To see if the account was included, go to “Lists” on your profile page. Click the list name, then click “Members.” You should see the account that you added.

- Sometimes people will put “no lists” in their Twitter profile. Please respect that request.

As an example, here’s my Twitter list of education reporters. Once you have created your list and added journalists, just click on the list to see a feed of tweets from those accounts. Over time, you will undoubtedly see patterns emerge in the topics and issues the journalists are covering.

As part of this effort, look for a calendar of public meetings in your community. For example, the Chicago City Clerk’s office maintains a calendar of council and committee meetings. These calendars typically include the date, time and location for the meeting, along with general public information and agendas. If there is a meeting your students are interested in, they can contact journalists on your list to see who might be covering it. Many journalists also live-tweet the meetings so people can know what’s happening in real time, especially if the meeting is of some importance.

Finally, this list can be useful when students want to engage with journalists directly, either by asking questions or offering their perspectives about news coverage. This is one of our indicators of civic engagement and can be an excellent avenue for student voice. And it provides you with information about your community from those whose job it is to determine what’s going on: local journalists and news organizations.

Using Checkology® to improve civil discourse in the classroom

For Nicole Finnesand, integrating current events into her lessons at a middle school in the southeast corner of South Dakota was daunting — until she encountered the News Literacy Project and its Checkology virtual classroom.

She teaches in Colton, a tiny town (population 676, according to 2017 Census estimates) about 25 miles northwest of Sioux Falls. As she put it during a recent phone conversation, “Sometimes, here in the Midwest, we feel very insular.”

You might think that such a small population would be more likely to share political beliefs, but Finnesand said that the students in her seventh- and eighth-grade language arts classes reflect the fractures in the country as a whole.

They are, she said, “very divided on social issues. That was very intimidating for me as an educator to talk about someone like Kim Jong Un or Donald Trump or any political anything in my classroom, knowing that the answer to it would be very polarized.”

A search for resources

Finnesand first heard the term “news literacy” after the 2012 election, but it wasn’t until 2016 — with the country more divided than ever — that she felt compelled to research resources that might help her discuss current events with her students and show them how to think critically about what was happening in their community, their country and the world.

That’s when she discovered Checkology, and it didn’t take her long to become a dedicated user.

“I have really loved all of the resources I’ve gained and the knowledge my students are walking away with,” she said. Also important, she added, are “the skills that they’re able to apply to their own reading and consumption of media.”

As an example, she said that before they were exposed to Checkology, some of her students would produce articles from the satirical publication The Onion as truthful sources for persuasive writing exercises.

“That was shocking,” she said, “but they had no idea what that whole genre of satire is. And certainly with the political climate of our country, there were students that were just shouting ‘fake news’ at things without knowing what that meant, or knowing what they’re saying, or what is fake news. They really couldn’t tell me.”

She knew that her students were capable — but that they didn’t know how to determine what was credible news or how to find it.

Enter Checkology — and a classroom transformed.

Civil discourse

Suddenly, students began coming to class not just with opinions, but with facts and legitimate sources to back them up. They may have strongly different views on some topics, Finnesand said, but civil discourse now feels possible.

Suddenly, students began coming to class not just with opinions, but with facts and legitimate sources to back them up. They may have strongly different views on some topics, Finnesand said, but civil discourse now feels possible.

“I think the Checkology platform gave us a tool that was engaging without telling the students, ‘Here’s the right answer, here’s the way to view it,’” she said. “It gave them talking points that we could all agree on or agree to disagree on. …

“We get to use our class as a space to discuss ‘Well, what are the two sides? And how do we know what’s real and what’s not real?’”

Finnesand has watched her students gain an appreciation for — and understanding of — quality journalism. One “lightbulb moment,” as she put it, came when they learned, through the Checkology lesson “Democracy’s Watchdog,” that journalists act as detectives and hold those with power in check. They have also enjoyed tying current issues to Checkology; “The First Amendment” gave them a starting point to discuss the recent efforts by the White House press office to lift the press credentials of CNN reporter Jim Acosta.

It’s a challenge for anyone, adults included, to consume news responsibly and discuss it civilly. But Finnesand says she has seen a real change in her students since introducing Checkology, and she believes that they can be agents of change.

“I’m learning with my students what kinds of things we can read about and agree to disagree and work on,” she said, adding: “Hopefully our country isn’t always so divided and we can still have conversations about issues without alienating each other.”

News literacy and conspiracy theories

Misinformation spreads rapidly on social media following natural disasters, mass shootings, terrorist attacks and other dramatic news events. In addition to seeing doctored photos and patently false “breaking news,” we’re also likely to be bombarded with conspiracy theories — another subset of misinformation. Since many of these involve alleged actions by the government, we need to make sure that our students have the news literacy skills they need to prevent them from believing these falsehoods and becoming distrustful of the government.

In his book The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory, published in 2013, Jesse Walker defined five types of conspiracy theories:

- The “Enemy Outside” refers to theories based on figures outside a community alleged to be scheming against it.

- The “Enemy Within” finds the conspirators lurking inside the nation, indistinguishable from ordinary citizens.

- The “Enemy Above” involves powerful people manipulating events for their own gain.

- The “Enemy Below” features the lower classes working to overturn the social order.

- The “Benevolent Conspiracies” are angelic forces that work behind the scenes to improve the world and help people.

In a 2018 study (PDF download) of people who believe in conspiracy theories, Mattia Samory and Tanushree Mitra of Virginia Tech’s computer science department examined 10 years of posts (and four crisis events) in the Reddit community r/conspiracy and defined three types of participants:

- “Veterans” are long-term active members of r/conspiracy.

- “Converts” were active in other discussions on Reddit and joined r/conspiracy in response to a specific crisis.

- “Joiners” became Reddit users and joined r/conspiracy specifically in response to a crisis or other event.

How do conspiracy theories manifest on social media? Let’s take a hurricane as an example. Amid the misinformation and hoaxes that typically appear before, during and after such storms (such as the inevitable “shark on the flooded highway” image), posts claiming that the government can alter the weather will start appearing. There will be references to chemtrails (the condensation trails from aircraft engines that conspiracy theorists say are laden with weather-changing chemical or biological agents) and to HAARP, an actual research program, based at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks, that studies the properties and behavior of the ionosphere. These posts will often link to sites or discussion groups that have compelling and detailed descriptions of how HAARP and other government programs can control the weather.

Without the skills to critically evaluate the content and sources for these posts, sites and other discussion groups, students can easily be persuaded that what’s being said is factual. They may even contribute to the viral nature of the ideas by sharing them — in short, becoming a “joiner.”

Samory and Mitra found that “joiners” demonstrated a very high level of engagement in the online discussions, posting longer and more detailed content that was comparable to that of the community’s “veterans.” “Converts” in these discussions tended to come and go, with lower levels of engagement overall. Perhaps most troubling is that the longer the “joiners” engaged in these communities, the more likely they were to become “veterans.”

This is where the importance of news literacy comes in. People who believe conspiracy theories are not necessarily the stereotypical “tinfoil hat” types. In a 2017 study, Stephanie* Craft, Seth Ashley* and Adam Maksl found that anyone can end up believing a conspiracy theory, since most of them are structured with a compelling story that provokes strong emotional reactions and has a connection to an existing bias or belief.

For their study, Craft, Ashley and Maksl surveyed 397 people to determine what they knew about the news media and the extent to which they believed several conspiracy narratives. Perhaps not surprisingly, they found a correlation between respondents’ knowledge about how the news media works and belief in conspiracy theories: “The greater one’s knowledge about the news media — from the kinds of news covered, to the commercial context in which news is produced, to the effects on public opinion news can have — the less likely one will fall prey to conspiracy theories,” the researchers wrote.

At the News Literacy Project, we emphasize the importance of news literacy as an antidote to misinformation and a catalyst for becoming a critical consumer of news and information. Discussing conspiracy theories with students can be tricky, and doing so is not typically part of the curriculum. But if students fall prey to this type of misinformation, their ability to be critical and open-minded about all types of information, including news, is compromised. And if their belief in conspiracy theories leads them to become fearful and cynical about the government, they are less likely to become active, informed and engaged participants in our country’s civic life.

*An earlier version of this post misspelled the first name of Stephanie Craft (not Stefanie) and the last name of Sean Ashley (not Astley).

Five ways to celebrate Media Literacy Week

Nov. 5-9 is Media Literacy Week — our favorite week of the year, when champions of news and media literacy raise awareness of the critical need and available tools to discern and create credible information as students, consumers and citizens.

Here are some things you can do each day during Media Literacy Week to support these efforts:

Monday: Double-check your facts (before you vote). Take The Easiest Quiz of All Time, then watch our video to see how others did. Warning: It’s not that easy!

Tuesday: Check your ballot! It’s Election Day, and news literacy education empowers the well-informed voters who keep our democracy strong.

Wednesday: Check in. Visit our online “booth” at the virtual fair hosted by the National Association for Media Literacy Education. On Wednesday between 3 and 5 p.m. ET, our own Jordan Maze will answer questions about our programs and about news literacy in general.

Thursday: Image check. People instinctively trust images more than words — but many images are manipulated or taken out of context. Brush up on your reverse image searching skills so you can teach someone else how to find out if that compelling photo is real or fake.

Friday: Check and correct (kindly). If you see that someone has shared misinformation online, let them know in the spirit of giving facts a fighting chance.

Everyone has to work harder than ever these days to avoid misinformation and manipulation. Keep fighting for facts!

Before you vote, pop your filter bubble by getting news from all sides

Americans head to their polling places in less than two weeks — and in each election cycle, it’s becoming more and more difficult to make sure that we actually know what we need to know before casting our ballots. (Check out our “Double-Check Your Facts” PSA to see how people did on The Easiest Quiz of All Time.)

To be active, engaged participants in the civic life of our communities, we all must take proactive steps to better understand the issues we care most about — especially since Facebook, Twitter and other social media have become, for many of us, our primary sources of information. By relying on these platforms for news, we’re likely to become encased in a filter bubble — a phenomenon that, in essence, limits what we read, watch and hear.

We end up inside these bubbles when the algorithms used by these platforms attempt to select content that they feel we want to see and that aligns with what they perceive as our personal preferences. And when our online friends and connections share our opinions, we’re trapped even more: We become insulated from opposing viewpoints, making it increasingly difficult to understand all sides of the issues. (Another description for this is the “echo chamber” effect — meaning that our beliefs are repeated and amplified by our connections.)

How do we pop these filter bubbles? We can’t expect any of the platforms to do it for us. We have to be proactive by engaging with new sources of information. Here are a few that will help.

Blue Feed, Red Feed

This site, from The Wall Street Journal, was launched several months before the 2016 presidential election. The concept is simple: Click on one of eight pre-selected topics (such as health care or immigration) and scroll through a series of Facebook posts that have been shared from sources that a study by Facebook has identified as “very liberal” or “very conservative.” Each post in the feeds has at least 100 shares, and the sources for the posts have more than 100,000 followers.

The strength of this tool is that it allows users to see the latest arguments for their selected issues side by side. People from across the political spectrum can consider their own beliefs against opposing viewpoints to come to a clearer understanding of their position — or perhaps change it to a new view.

ISideWith.com

This site was started in 2012 by Taylor Peck, a political analyst and marketing expert, and Nick Boutelier, a web designer and developer, who wanted to find ways to increase voter engagement and knowledge. Users can choose from more than 30 countries and select from 22 languages (including several variations of English).

For U.S. voters, the site has a 2018 midterm voter guide that asks users to rate their beliefs on a wide range of issues — economic policy, foreign policy, education, health care and more — and then presents information about candidates whose views concur with the users’. There are also guides to candidates for Congress and state legislatures. In the Polls section, users can see how others have answered the questions about their beliefs on issues, with both sides represented on the same page.

This site has an almost overwhelming amount of information — but it’s this comprehensiveness that makes ISideWith an excellent resource.

Vote Smart

Originally known as Project Vote Smart, this nonpartisan organization was founded in 1992 by Richard Kimball, a former Arizona state senator who had run unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate against John McCain in 1986. Users can enter their ZIP code to see who currently represents them (federal, state and local offices) and who is running for office; when they click on a name, they can learn more about the official’s or candidate’s voting record, positions, speeches and funding. Similar to ISideWith, Vote Smart created Vote Easy, which allows users to explore candidates running for federal office (in 2018, the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House) and their positions on key issues.

Other resources

The challenge with sites such as Vote Smart and ISideWith is that they tend to focus on enabling voters to find candidates whose political beliefs reflect their own. This actually serves to reinforce the filter bubble. If we look only for candidates with positions that agree with ours, we’re not really learning about opposing viewpoints.

ProCon.org focuses on the issues, not individual candidates. Users choose from an extensive list to see arguments for and against specific topics. Examples include:

- Should student loan debt be easier to discharge in bankruptcy?

- Should the drinking age be lowered from 21 to a younger age?

- Should marijuana be a medical option?

- Should bottled water be banned?

The site provides citations for all sources listed in the results. The arguments are listed side by side for easy comparison.

BalancedPolitics.org also lists arguments for specific positions side by side and provides background and links to additional resources. Finally, Debate.org is an online community (free to join) where members can vote and contribute their own opinions to current issues.

Civic engagement is more than voting. We must find ways to increase our knowledge and understanding of the issues that affect us and our communities. To do so, we first must be aware that we are inundated with information through our social media feeds and that we must critically evaluate everything that we encounter. Next, we need to seek out content that shows us opposing positions and ideas. What we find can either reinforce what we already believe or allow our positions to evolve.

When we burst our filter bubbles and are ready for our positions to be challenged, we’re taking an uncomfortable but important step. It’s one we have to take, though, if we want to become active and engaged participants in civic life — and informed voters.

Before you vote, double-check your facts

Election Day is just two weeks away — and in each election cycle, it gets more and more difficult for us to make informed decisions before casting our ballots. As political rhetoric tips toward misinformation frenzy, it’s increasingly difficult to discern fact from fiction and truth from outright falsehoods.

Russian troll farms, bots and other types of political chicanery are certainly part of the problem — but the perception that misinformation is spread only by people who are intentionally trying to muddy the waters is far from accurate. It’s the unintentional sharing of misinformation that really causes misinformation to spread. Certainly, most of us don’t go out of our way to share bad information with our family members and friends. But that doesn’t mean we haven’t — even a casual “like” or retweet can give misinformation a broader audience.

So we at the News Literacy Project have teamed up with Edelman, a global communications marketing firm, to create a public service campaign that we’re calling The Easiest Quiz of All Time. Hosted by comedian and filmmaker Mark Malkoff, this humorous street quiz tests passers-by about frequently misremembered facts. Contestants learn, for example, that Darth Vader did not actually say “Luke, I am your father.” They also learn that overconfidence and a failure to double-check what you think you know can lead to incorrect answers — and, potentially, uninformed decisions.

As we were making this video, I was reminded once again that the skills to be a well-informed and active participant in civic life should not be taken for granted. If you see something that sounds like it might not be true, take a minute to find out before you pass it on. The spread of misinformation is not inevitable, and stopping it comes down to each of us taking a little time to double-check the facts.

We’re urging you to share this video between now and Election Day with your family, your friends, your neighbors, your co-workers and your networks, using the hashtag #doublecheck.

And most importantly, remember to vote — after double-checking your facts!

‘Practicing Quality Journalism’: ¡Ahora en español!

We are diversifying our news literacy efforts in all sorts of new ways, and here’s one that’s truly exciting: One of the most popular lessons in our Checkology® virtual classroom is now available in Spanish!

“Practicing Quality Journalism”/“Practicando el periodismo de calidad” is a game-like simulation in which students assume the role of rookie reporters to cover a breaking news event. The lesson is taught by Enrique Acevedo — news anchor of Noticiero Univision: Edición Nocturna (Univision News: Late Edition), special correspondent for the Fusion Media Group and an experienced journalist who has covered breaking news around the world for print, broadcast and digital media. In this lesson, which he delivers in both English and Spanish, Acevedo guides students as they work to meet the standards of quality journalism while reporting on an accident that has caused a tanker truck to leak a mysterious green slime.

“I’m thrilled to be part of NLP’s effort to reach Spanish-language audiences,” Acevedo said. “I can’t think of a better contribution to the future of journalism and the free press than our partnership with NLP. As journalists, we need to make sure everyone has access to these important tools.”

“Practicing Quality Journalism”/“Practicando el periodismo de calidad” is available with either Basic or Premium levels of access to the virtual classroom. Gracias, Enrique — and thanks also to the Facebook Journalism Project for making this, our first lesson in Spanish, possible!

To sign up for Checkology or to learn more, click here.

A guide to understanding — and debunking — misinformation

Civic engagement in action: A voter registration table, hosted by the League of Women Voters, at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia.

As civics education is increasingly part of the national conversation, and as school districts and state legislatures increasingly call for more of it, we need to have a good understanding of what civic engagement looks like for young people in the 21st century. How many civic actions from previous generations remain unchanged? How many have been affected, in both good ways and bad, by the enormous technological changes of the last two decades? And what new forms of civic engagement do we need recognize, refine and support in the classroom?

NLP’s approach to civic engagement consistently builds on news literacy as a foundation. After all, credible information is the very basis for civic literacy and engagement; it is what drives meaningful civic actions. If we don’t have that foundation, misinformation can cause people to take actions that are civically disempowering — not in their interests, or in the best interests of the republic.

Here are 10 important indicators of civic engagement that we’ll be discussing over the coming weeks (these assume that students already have the key skills needed to navigate today’s information landscape):

10 Indicators of Civic Engagement

- Pay attention to and understand how misinformation spreads on social media and debunk misinformation or false comments in a constructive, responsible manner.

- Pay attention to, and understand, issues being debated locally, statewide or nationally.

- Participate in a discussion about politics or current events — in school, with my friends or family, or online.

- Cast a ballot in an election (when I’m old enough) as a well-informed voter.

- Pay attention to, and understand, issues relating to individual freedom of expression and protected speech in the United States and abroad.

- Contact a reporter or news organization by email, social media or phone.

- Pay attention to, and understand, ongoing discussions about journalism and the state of the news media, including press freedom in the United States and internationally.

- Document something in my community and share it with others.

- Question or engage in conversations with my elected officials by email, social media or phone.

- Volunteer or advocate for a cause, idea, mission-driven organization or political campaign — one that aligns with my personal beliefs, that I’ve researched and that I have a deep understanding of.

In the coming weeks, I’ll be posting more detailed explanations and examples of how to connect specific news literacy skills with these civic actions. Today, let’s start with the first indicator: Pay attention to and understand how misinformation spreads on social media and debunk misinformation or false comments in a constructive, responsible manner.

As students become more immersed in the news and other information that surrounds them, the more misinformation, hoaxes, viral rumors and propaganda they will come across. Critically evaluating what they read, watch and hear and identifying the various types of misinformation they encounter are critical news literacy skills. Once they can do this, they can take an active, constructive role in debunking misinformation.

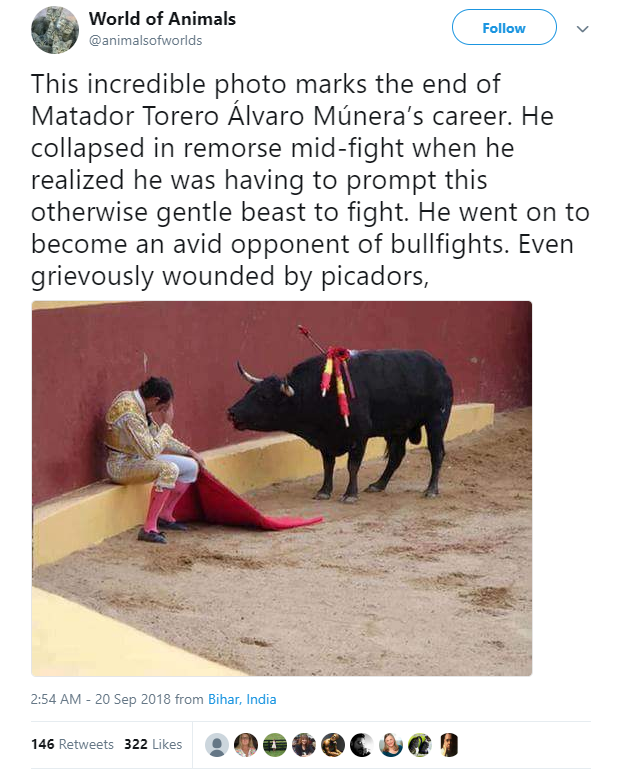

On Sept. 20, this tweet showed up in my feed:

To be sure, it’s a powerful image and message — one that animal lovers would readily agree with and quickly retweet. My critical eye thought that it was a little too perfect. There isn’t enough information in the tweet to provide credible evidence for what it says. When I scrolled through the replies, I quickly discovered that a few people had already called out the image.

I did a reverse image search and found two key articles debunking both the image and the explanation. It turns out that the photo is of a different bullfighter. In addition, what the bullfighter is doing is actually part of the act. As explained in the blog The Last Arena and confirmed by the fact-checking site Snopes.com:

“Sitting on the ‘strip’ around the ring after the sword has been placed in the bull is a known desplante, or act of defiance, within the part-scripted, part-improvised spectacle that is the corrida de toros.”

The bullfighter mentioned in the original tweet did eventually become an animal rights activist, but only after he was left permanently disabled after being gored by a bull.

This tweet reinforces the importance of reading through the comments or replies before retweeting. Others responded to it by sharing the same links I referenced above, tagging it #fakenews, calling out the original tweet for “harming the cause” or simply describing it as “utter tosh.” Yet some replied favorably, accepting the tweet as being true without checking further.

Some of the messages debunking the tweet were more effective than others — and the key to this civic action is teaching students the most effective ways to do this. In two published meta-analyses of studies about correcting misinformation from a variety of topics, researchers described strategies that are more effective at swaying beliefs and countering false information – along with those which are ineffective.

In their 2017 study, “Debunking: A Meta-Analysis of the Psychological Efficacy of Messages Countering Misinformation,” authors Man-pui Sally Chan, Christopher R. Jones, Kathleen Hall Jamieson and Dolores Albarracín made three key recommendations.

- Reduce the generation of arguments in line with the misinformation.

- Create conditions that facilitate scrutiny and counterarguing of misinformation.

- Correct misinformation with new detailed information, but keep expectations low.

If the debunking message includes arguments that are in line with the misinformation, it’s “difficult to eliminate false beliefs,” they wrote. The emphasis should be on the counter-argument or on the facts being used to debunk the misinformation — not on the original belief or false claim. Simply labeling the misinformation as being “wrong” or “false” also makes accepting the debunking message less likely.

Students should create a counter-message that is detailed and supported by facts — but don’t expect it to always work. The stronger someone believes misinformation initially, the harder it is to change their view.

A similar study, “How to unring the bell: A meta-analytic approach to correction of misinformation” by Nathan Walter and Sheila T. Murphy, highlights other factors to emphasize when debunking misinformation:

“Appeals to coherence tended to be best at correcting misinformation, compared to fact-checking and source credibility. In other words, providing alternative explanations that were internally coherent was more successful than providing ratings of the accuracy of specific statements or highlighting the credentials of a source.”

Relating to the recommendation of keeping expectations low, Walter and Murphy found that it was more difficult correcting misinformation relating to politics and science than misinformation in other areas, such as health, crime and marketing.

If you want your debunking message to be read loud and clear:

- Don’t just label something as “wrong,” “false” or “fake.”

- Don’t focus solely on fact-checking the content or source of misinformation.

- Make your message clear and detailed, and support it with facts.

- Emphasize an alternative explanation that brings clarity to the subject.

- Don’t expect everyone to readily accept your message.

People who pass on misinformation shouldn’t feel as if they are being personally attacked. In a way, a good debunking message is one in which those who shared a falsehood feel as if they came to the right conclusion by themselves — with a little nudge from you.

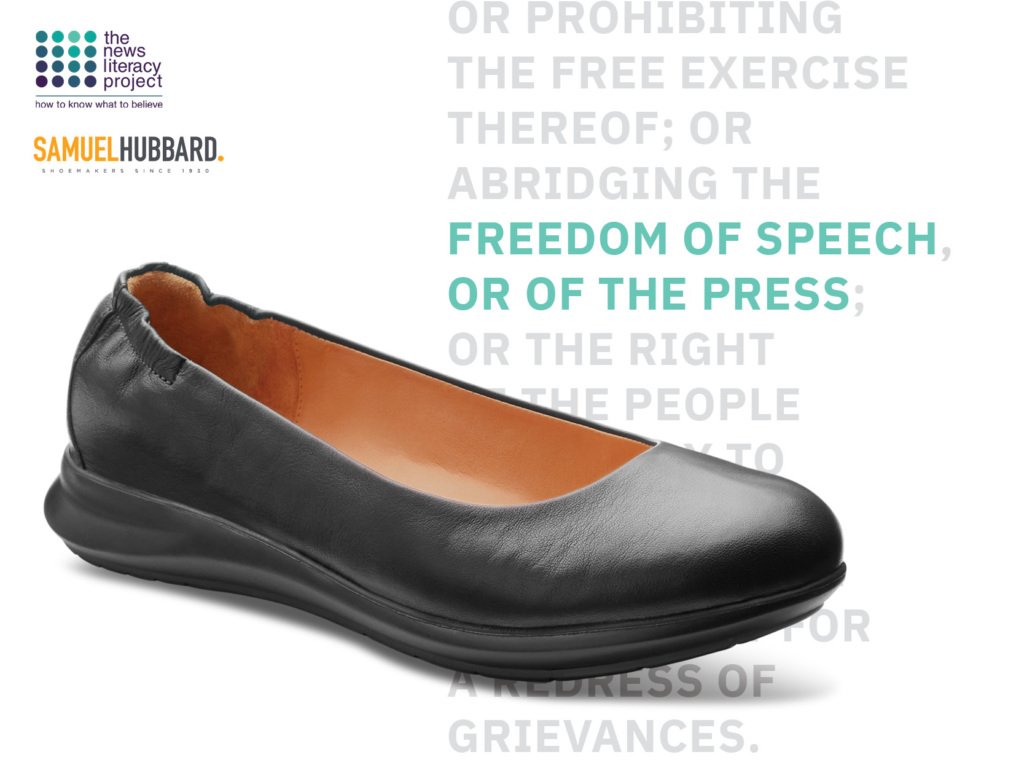

New line of support for the News Literacy Project (and democracy)

I’m always pleased to announce new partners in news literacy, but this one is especially gratifying because it offers support in a distinctive way. The Samuel Hubbard Shoe Company has shown generosity matched by creativity in pledging to give $20 to the News Literacy Project for every pair of shoes bought online from its new Freedom Shoe line for women.

Needless to say, I’m thrilled that the donations will help us expand our news literacy education efforts by sponsoring our weekly newsletter, The Sift, for the entire school year. But here is, well, the kicker: The First Amendment is literally built into the offer.

To be exact, every shoe that is part of this line will have the First Amendment engraved on its sole. That means that when people buy a Freedom Shoe, they are bearing (and wearing) a foundational element of our Constitution.

Samuel Hubbard will donate to us through March 1, 2019, or until donations reach $100,000, whichever comes first. It’s also promoting us in a company brochure about the First Amendment that will be shipped with every pair — which means even more people will learn about us and champion news literacy in their communities.

We at the News Literacy Project are pushing to get into as many schools as possible to help students understand the powerful role the press plays in our country and the protections guaranteed under the First Amendment. This partnership with Samuel Hubbard promises to reach the public in a whole new (and fun) way, giving people instant access to a crucial part of news literacy and of our democracy.

A recent study found that only 3 percent of Americans know all five rights guaranteed by the First Amendment (though 36 percent can name at least one). I make that point to underscore how this agreement will provide support in multiple ways: If you wear these shoes, you are supporting our cause financially as well as spreading word of the First Amendment. And there is every reason to believe that you’ll be providing great support for your feet, too!

Samuel Hubbard Shoe Company founder and CEO Bruce Katz says this about designing the Freedom Shoe line: “The First Amendment is a simple and elegant statement of where our freedom begins — and it’s essential that today we remember what it stands for.”

Thank you, Samuel Hubbard!

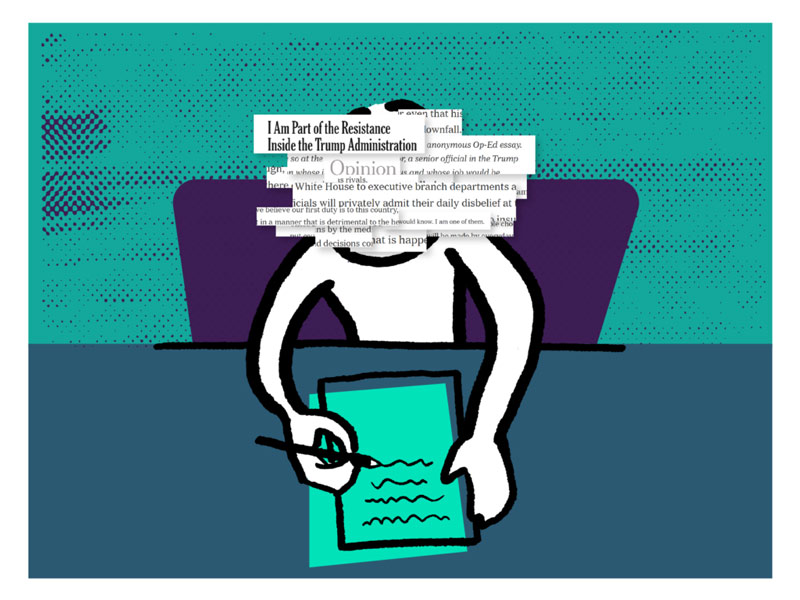

Evaluating unnamed sources in news reports

On Sept. 5, the editors of The New York Times’ opinion page took what they called “the rare step of publishing an anonymous Op-Ed essay.” The action raises an important issue in journalism and an opportunity to teach students about evaluating unnamed sources in the news.

By “unnamed sources,” I am referring to the people who provide information published in news reports, editorials and other opinion pieces but whose names are not given. (It’s important to remember that the source’s identity is unknown to us — the readers, viewers and listeners — but is known by the journalist and, usually, at least one editor at the news organization.)

Being a critical consumer of news includes understanding and evaluating different types of sources — such as official sources, eyewitness sources, raw video and documents — to determine whether a news article is credible. Evaluating the words of individuals who are not named requires a closer look at both the journalist and the news organization.

Most news articles routinely attribute key facts to a source who is identified by name and, often, by title — information telling us why the source is in a position to know about and comment on the topic. When the source is unnamed, news consumers should consider two key elements: why the source desires anonymity, and what is behind the source’s decision to share this information.

Here is how The Associated Press, a global news agency that produces more than 2,000 news stories per day, defines the terms used in granting anonymity (parenthetical information in the definitions is not from AP). Other news organizations may have their own definitions of these terms. Both the reporter and the source must agree to these ground rules before an interview.

- On the record: The information can be used with no caveats, quoting the source by name.

- Off the record: The information cannot be used for publication. (But the reporter can use this knowledge to get the information verified elsewhere.)

- On background: The information can be published but only under conditions negotiated with the source. Generally, the sources do not want their names published but will agree to a description of their position. (Other news outlets may refer to this as “not for attribution”; some may even distinguish between “not for attribution” and “on background.”)

- On deep background: The information can be used but without attribution. The source does not want to be identified in any way, even on condition of anonymity.

Why do journalists use unnamed sources, especially since it might endanger the trust the public has in their work? After all, the public should know whether these sources are in a position to be fully informed on the matter or are offering a skewed version that serves their purposes, not ours.

The news organization’s obligation

For starters: Good news organizations do not publish information from unnamed sources without consideration and thorough vetting. As reporter Jason Grotto of ProPublica Illinois wrote, his organization’s ethics guidelines allow sources to remain unnamed “only when they insist upon it and when they provide vital information,” “when there is no other way to obtain that information” and when the journalist knows that the source is “knowledgeable and reliable.”

Typically, journalists share the names of these sources with their editors, who assess whether those criteria are met.

As the Society of Professional Journalists’ ethics code notes, “Consider sources’ motives before promising anonymity. Reserve anonymity for sources who may face danger, retribution or other harm, and have information that cannot be obtained elsewhere.”

Motives, of course, vary. The source may be acting as a whistleblower, exposing corruption or other illegal conduct. The source may feel compelled to share information with the public that is being withheld for some reason. Or — and good journalists know this — the source might have personal interests at heart. That does not necessarily disqualify the accuracy of the information, but it is why one standard of quality journalism is verification of facts by multiple sources.

News organizations that use unnamed sources owe it to their readers, viewers and listeners to clarify, as much as possible, why the source was granted anonymity, and why the source’s motives did not invalidate the value of the information.

The news consumer’s obligation

The challenge for news consumers is that the use of unnamed sources provides no outside way to verify what the journalist has written. We must decide whether to trust the journalist and the news organization. Fortunately, there are some actions we can take that help build that trust.

When evaluating a news article that uses unnamed sources, take a step back and engage in lateral reading* about the journalist who wrote the article and the news organization that published the report. Take a look at other articles by that journalist: How often does he use unnamed sources? (Is he lazy, or is he privy to officials who have great — but classified — information?) Does she write about this particular subject regularly, indicating that she has in-depth knowledge? Does the journalist also write opinion pieces? (If so, this could indicate a bias that must be evaluated.)

Consider, too, whether the journalist has provided sufficient context to determine whether the source is reliable and credible. In “When To Trust A Story That Uses Unnamed Sources,” Perry Bacon Jr. of FiveThirtyEight gives five details that readers should look for when considering a story that uses unnamed sources. His follow-up post, “Which Anonymous Sources Are Worth Paying Attention To?,” explains how to evaluate the description applied to an unnamed source — such as “a Pentagon official,” “a person familiar with” or “a law enforcement official.” The more details the journalist provides about a source, the more comfortable we can be trusting what that source has to say.

More fundamentally, has the article explained why the source was granted anonymity? Explaining why a source isn’t named — for example, attributing behind-the-scenes information about congressional action to “a committee aide who was not authorized to speak publicly about the meeting” — is something we can evaluate. Check to see if the news organization has a published policy on using unnamed sources (such as these from The Washington Post and NPR).

We shouldn’t dismiss the use of anonymous sources out of hand. Particularly when reporting about the government, journalists often must rely on sources who have a justifiable concern about being named; at the same time, they must recognize that using anonymous sources may make their work appear less credible. In 2013, Margaret Sullivan, then the public editor of The New York Times, quoted a national security editor who said of government sources, “It’s almost impossible to get people who know anything to talk,” especially on the record. “So we’re caught in this dilemma.”

As for that op-ed in The New York Times, the author is described as “a senior official in the Trump administration whose identity is known to us and whose job would be jeopardized by its disclosure.” Whether the opinion page editors made a good decision in publishing the piece remains up for debate. And that’s what we, as critical consumers of news, should be able to do: Evaluate the available information and make our own determination about the credibility of what was published.

Further reading:

- Chapter 59: Sources of information (The News Manual)

- “Which Anonymous Sources Are Worth Paying Attention To?” (Perry Bacon Jr., FiveThirtyEight)

- “When To Trust A Story That Uses Unnamed Sources” (Perry Bacon Jr., FiveThirtyEight)

- “How do you use an anonymous source? The mysteries of journalism everyone should know” (Margaret Sullivan, The Washington Post)

- “Using anonymous sources with care” (H.L. Hall, Journalism Education Association)

- “What Does ‘Off the Record’ Really Mean?” (Matt Flegenheimer, The New York Times)

**The lateral reading concept and the term itself developed from research conducted by the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG), led by Sam Wineburg, founder and executive director of SHEG.

Teachers, it’s time to embrace Wikipedia

Roman Pyshchyk / Shutterstock.com

Fact-checking is an essential skill that we need to teach students — and to reinforce as a habit for daily consumption of news and other information. Do a search on just about any topic, and there is a high likelihood that a Wikipedia article will come up in the initial results.

You may find this next statement surprising, but hear me out: When it comes to verifiable, objective facts, Wikipedia is an excellent starting point for fact-checking, and one we should encourage students to use.

Let’s start by talking about what Wikipedia is and whether it should be considered reliable.

According to its own “about” page, “Wikipedia is a portmanteau of the words wiki (a technology for creating collaborative websites, from the Hawaiian word wiki, meaning ‘quick’) and encyclopedia. Wikipedia’s articles provide links designed to guide the user to related pages with additional information.”

In effect, Wikipedia is designed to be a jumping-off point to additional, more detailed sources. This is a particular strength in that articles without proper referencing can be rejected. Sources that are not acceptable include:

- Blogs.

- Social media.

- The subject’s own website.

- Press releases.

- Tabloid journalism.

There is a learning curve for those contributing to Wikipedia. They must learn to write according to Wikipedia’s standards; they also must learn the technical aspects of editing articles. According to Wikipedia, “All articles must strive for verifiable accuracy, citing reliable, authoritative sources, especially when the topic is controversial or is on living persons. Editors’ personal experiences, interpretations, or opinions do not belong.” Contributors may be asked to justify their edits. Some edits may be changed by another user.

Wikipedia’s standards, you’ll see if you review them, are quite high and follow many of those set forth for academic writing or journalism.

A common criticism of Wikipedia is that anyone can edit an article at any time. This is not entirely accurate. While most articles can be edited by anyone, even anonymously, there are different levels of protection for articles to prevent acts of vandalism and partisan “edit wars.” For some of these levels, only a confirmed user (registered users with accounts created a specified number of days ago and with a number of accepted edits to articles) can edit an article; under the most restrictive protection, only “official” Wikipedia editors can make changes. These levels of protection are generally determined by either moderators or Wikipedia administrators.

The articles on Wikipedia are continually monitored by site administrators, moderators, confirmed users and bots. (Bot aren’t always bad: According to Wikipedia, a bot is an “automated tool that carries out repetitive and mundane tasks to maintain the 45,699,154 pages of the English Wikipedia. Bots are able to make edits very rapidly” for routine edits.) Some articles are monitored more closely than others, but generally, if someone vandalizes an article by editing it to include false or malicious information, corrections are made in a relatively short period of time.

Article vandalism is one of the most common problems on the site. A study published in 2015 showed that controversial topics (specifically in science, such as evolution and global warming) had more edits and word changes than articles on non-controversial topics. But the study also showed that many of those edits were corrections to the vandalism. I would argue, as did the authors, that this means we should evaluate Wikipedia as critically as we do any other source, rather than disregard it entirely.

That criticism that anyone can edit Wikipedia at any time? In my view, that’s a strength, because the overwhelming number of people who edit Wikipedia do so to make the site better and more useful as a source of information. That is why I joined as a confirmed user and contribute when I have time. As of this writing, there are 34,331,716 registered “Wikipedians,” with over 121,000 of those being active editors.

A last note about the site’s reliability: If you search on Google for “reliability of Wikipedia,” the first search result is a Wikipedia article titled “Reliability of Wikipedia.” Skipping that for now, let’s look at some other sources. In 2016, a group of German researchers examined both the English and German versions of Wikipedia using drug information as a test subject area. They found that while Wikipedia articles were rated at 83.8 percent for completeness, the information published in the articles was 99.7 percent accurate. In 2001, Live Science compared Wikipedia with the more scholarly Encyclopedia Britannica and found little difference between the two for accuracy of selected articles. (Remember, I’m focusing on using Wikipedia for fact-checking, not in-depth research.)

Here are some ideas for what specifically to teach students about using Wikipedia.

An excellent starting point to introduce Wikipedia’s value is to teach students the requirements of editing an article on the site. Have students examine Wikipedia’s Five Pillars, which summarize the “fundamental principles of Wikipedia.” Discuss the criteria for an article to be considered a “good article” or a “featured article”; I expect that many students will be surprised by the strictness of the criteria. Explore the talk pages (connected to articles and where users debate edits, suggestions and content) of prominent articles to see what edits are being discussed. Discuss the requirements to be a Wikipedia moderator or administrator.

If you want to go a step further, consider having your students join a WikiProject — a group of people working together to improve articles relating to a specific topic. In a WikiProject, there is usually a list of topics and articles that have varying levels of priority. Some are articles that need to be researched and created. Others are stubs (short articles) that need to be expanded. There are articles that need to be edited to be in line with Wikipedia’s standards of sourcing and neutral point of view.

If we’re going to empower our students to be independent fact-checkers and critical consumers of information in all its forms, we need to recognize that Wikipedia is a deep, reliable source of factual information. As a starting point for fact-checking, Wikipedia is a powerful tool; in their day-to-day efforts to separate fact from fiction, students can — and should — use it confidently.

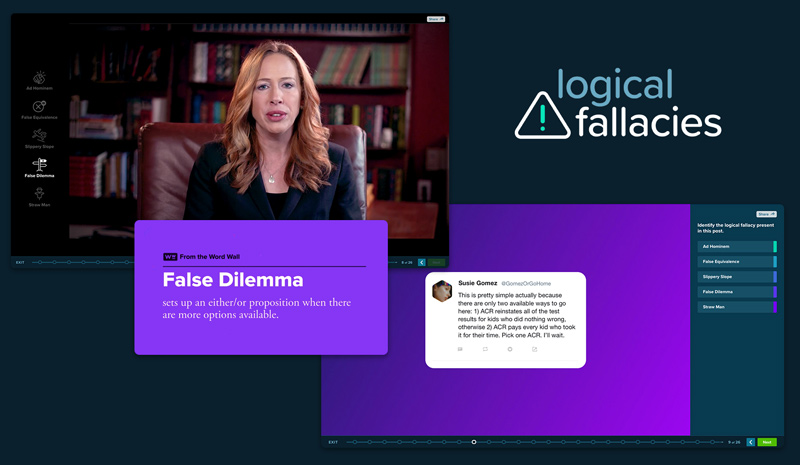

Evaluating arguments and identifying logical fallacies

In a previous post, I discussed holding controversial conversations about current events in the classroom. As an extension of that topic, I’m sharing some ideas and resources about a challenge common in public debate, commentary and social media: the use of logical fallacies.

Just what are logical fallacies? The Purdue University Online Writing Lab (OWL, one of my favorite resources) describes them as “common errors in reasoning that will undermine the logic of your argument. Fallacies can be either illegitimate arguments or irrelevant points and are often identified because they lack evidence that supports their claim.” Examples include:

- Ad hominem: An attack on the person making an argument, rather than on the argument itself.

- False dilemma: An argument suggesting that only two options exist, when in fact there are more. Also called the “either/or,” “false choice” or “black and white” fallacy.

- False equivalence: Opposing arguments falsely made to appear as if they are equal.

- Slippery slope: An argument suggesting that a course of action, starting from a simple premise, will lead to disastrous results.

- Argumentum ad populum: An argument believed to be sound and true because it is popular. Usually referred to as “the bandwagon.”

In today’s social media world of character limits, memes and overflowing feeds, it’s increasingly difficult to convey a persuasive argument that is supported by evidence — and it’s really easy to share a short blast of opinion with a logical fallacy at its center. Those sorts of posts are notable specifically for their lack of credible evidence to support a claim or an argument, with fallacious reasoning used to fill the gaps. Here’s an example:

We must stop kids from playing video games. You buy them a game system and it’s only a matter of time before they’ll be fat and lazy, never leaving your basement. Parents all over this country agree that video games have no value whatsoever. We must either ban video games entirely for kids under the age of 16 or prepare for a generation of high school dropouts. The makers of these gaming systems are clearly greedy, manipulative predators out to keep our children addicted to their screens.

As young people engage in conversations about political, social or cultural issues, they need to be able to recognize logical fallacies — not just when others use them, but when they’re framing their own arguments. The ability to closely evaluate claims and arguments is a key element of critical thinking.

In “Arguments & Evidence” — a new lesson in our Checkology® virtual classroom — we discuss five of the most common types of logical fallacies. In developing that lesson, I researched resources for evaluating arguments and spotting logical fallacies. These are among the ones that I found most informative; they provide definitions, examples and context:

- “Monty Python and the Quest for a Perfect Fallacy”: This comprehensive lesson plan was developed by the Annenberg Classroom, a project of the Leonore Annenberg Institute for Civics at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center. It includes definitions, examples and reproducible materials for students.

- “Thou Shalt Not Commit Logical Fallacies”: This site was developed by The School of Thought International, a nonprofit that develops education resources on “critical thinking, creative thinking, and philosophy.” It has flashcards and posters — available both for purchase and as free PDF downloads — that integrate logical fallacies as part of critical-thinking exercises.

- An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments: This free online book by Ali Almossawi, an engineer at Apple who writes about both critical thinking and computer science, contains wonderful illustrations and explanations for logical fallacies.

- Rational Wiki: “Logical fallacy”: Rational Wiki is owned and operated by the RationalMedia Foundation, a nonprofit whose mission “is to promote and defend science, critical thinking and public interest dialog in a free and open forum.” This comprehensive article offers great examples of logical fallacies focusing on science, statistics and studies.

- “18 Common Logical Fallacies and Persuasion Techniques”: In this Psychology Today article, Christopher Dwyer, a post-doctoral researcher in psychology at the National University of Ireland, describes “18 forms of persuasion techniques, illogical argumentation and fallacious reasoning” commonly encountered in social media.

- “Spot the Flaw in a Politician’s Argument With This Guide to Logical Fallacies”: This guide from Lifehacker focuses on fallacies used by politicians.

If you have a go-to resource for teaching logical fallacies, or another suggestion for incorporating such lessons into the classroom, please share it with me (Twitter: @MrSilva; email: [email protected])!

A reimagined Checkology®: More power in our fight for facts

As the urgency grows for a more news-literate nation, so does demand grow for the News Literacy Project. And today we are more prepared than ever to meet that demand: I’m thrilled to announce the launch of version 2.0 of our Checkology virtual classroom, an expansion made possible thanks to a $1 million grant from the Facebook Journalism Project.

When we introduced the Checkology platform in May 2016, we knew that it would be a powerful way to achieve the goal I set 10 years ago when I founded the News Literacy Project — to give students the skills to become informed and active participants in the civic life of their communities. And powerful it has been: Checkology has proved to be a sophisticated tool to teach students how to assess the flood of information that hits us every day … to separate fact from fiction … to know what to trust, share and act on.

Version 2.0 of Checkology hones the tools that we know are working. It includes new lessons on teacher-requested topics, along with the voices of even more journalists. This update also improves the ways that educators can customize the curriculum to meet their own objectives and their classrooms’ needs.

I’d like to highlight some of our new resources:

- In a lesson on press freedoms around the world, NPR’s Soraya Sarhaddi Nelson explains the ways through which governments can restrict or weaken the press. The lesson also includes videos of journalists recounting their experiences reporting in several countries with varying degrees of press freedom.

- Kimberley Strassel, a member of The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board, hosts a lesson on arguments and evidence, walking students through the virtual experience of an event and its aftermath — raw footage, viral rumors and contradictory claims — that students must then evaluate.

- The Check Tool expands to become the Check Center. Through four key areas, this resource helps students learn to incorporate new ways to think critically about what they encounter online.

Checkology continues to shine a light on crucial aspects of the Information Age and democracy through its lessons about the First Amendment, the role of algorithms in personalizing what we see, and categories of information. In short, it reflects every aspect of what it means to be news-literate today, offering students absorbing ways to learn in real-world settings.

Our partnership with the Facebook Journalism Project is also enabling us to create what we’re calling a “global playbook” for news literacy. The News Literacy Project will offer guidelines and guidance to 10 organizations that are building news literacy efforts in 10 countries. We’ll be telling you more about that soon.

I invite you to check out these lessons — “InfoZones” (categorizing information), “Democracy’s Watchdog” (investigative journalism) and “Practicing Quality Journalism” (covering a breaking news event) — then tell us what you think by emailing us at [email protected]. (And if you’re an educator, please register for an account!)

Understanding and evaluating endorsements

The 2018 midterm elections are only three months away — and as political candidates ask people for their support, they will often feature the endorsements they receive from editorial boards, political organizations, unions and even celebrities. These endorsements can be a useful resource as voters decide how to cast their ballots, and they are often an indication of a candidate’s popularity among specific sectors of the electorate.

Yet students may not realize that these endorsements are, in their own way, a form of persuasion. They must be carefully evaluated, and the motives for making them examined. Here is an overview of different types of endorsements typically seen during a campaign, along with links to resources.

Endorsements by a newspaper’s editorial board

A newspaper’s editorial board is usually composed of journalists, each with expertise in specific topics, who together determine the publication’s “voice” on a variety of issues. Editorials — including political endorsements — reflect the opinion of the newspaper as agreed upon by a majority of the editorial board. Editorials are part of a publication’s opinion section, and the editorial board is typically kept separate from the news-gathering process.

Each outlet has its own process for making endorsements; some never do so, and some do so only for specific races. Candidates or their representatives may appear in person before the editorial board to answer questions. Occasionally, an endorsement decision may take the form of a closed-door debate between candidates. In many cases, candidates submit answers to lengthy questionnaires prepared by the board. After vetting the candidates, the board meets to deliberate and decide whether (and whom) to endorse; their decision is then published as an editorial.

- “Political Newspaper Endorsements: History and Outcome” (Micah Cohen, FiveThirtyEight/The New York Times).

- “A Brief History of Newspaper Endorsements” (Ethan Trex, Mental Floss).

- “Newspaper Endorsements: Do They Matter?” (Sharon Shahid, Newseum).

Endorsements by a political party

A political party’s endorsement of a candidate is typically an indicator that the candidate agrees with most or all the key statements in the party’s platform. The platform is an official document that outlines the party’s ideals or its political goals. It offers guidance to party members on how they should advocate for — and vote on — political and social issues.

The national party platforms are debated and finalized every four years, in advance of the presidential nominating conventions:

In addition, state and local party organizations may also publish platforms, focusing on issues that are most important to voters in a specific state or locality:

- 2018 platform of the Texas Democratic Party.

- 2018 platform of the Texas Republican Party.

- “How the Texas Democratic and Republican Party Platforms Compare” (Naema Ahmed, Cassi Pollock and Alex Samuels, The Texas Tribune).

Endorsements by a political organization/political action committee

These endorsements are generally focused on a single political or social issue. They can come from advocacy or special interest groups, industry lobbying organizations, community groups, nongovernmental organizations or other similar groups. The key to understanding an endorsement from one of these organizations is to focus on the specific issues that are central to its mission.

Endorsements by a union

Like political organizations, labor unions have political priorities and goals that are aligned with the needs of their members. The process varies depending on whether the union is national, state or local; it often involves a questionnaire or interview with a committee or panel formed by the union. This group will make recommendations that may be voted on by the union’s delegates or its full membership.

- “A beginner’s guide to understanding labor politics” (Philip Bump, The Washington Post).

Endorsements by celebrities

In rhetoric, this type of endorsement is known as the “bandwagon effect”or “appeal to popularity”; it wants you to vote for a candidate simply because a celebrity says you should.

For example, candidates hope that endorsements from popular sports figures will sway fans of the team or sport associated with the endorser. In the 2016 presidential campaign, former Chicago Bears coach Mike Ditka and former Indiana University basketball coach Bobby Knight supported Donald Trump, while two of the most popular players in the National Basketball Association — Stephen Curry of the Golden State Warriors and LeBron James of the Cleveland Cavaliers — backed Hillary Clinton.