A guide to understanding — and debunking — misinformation

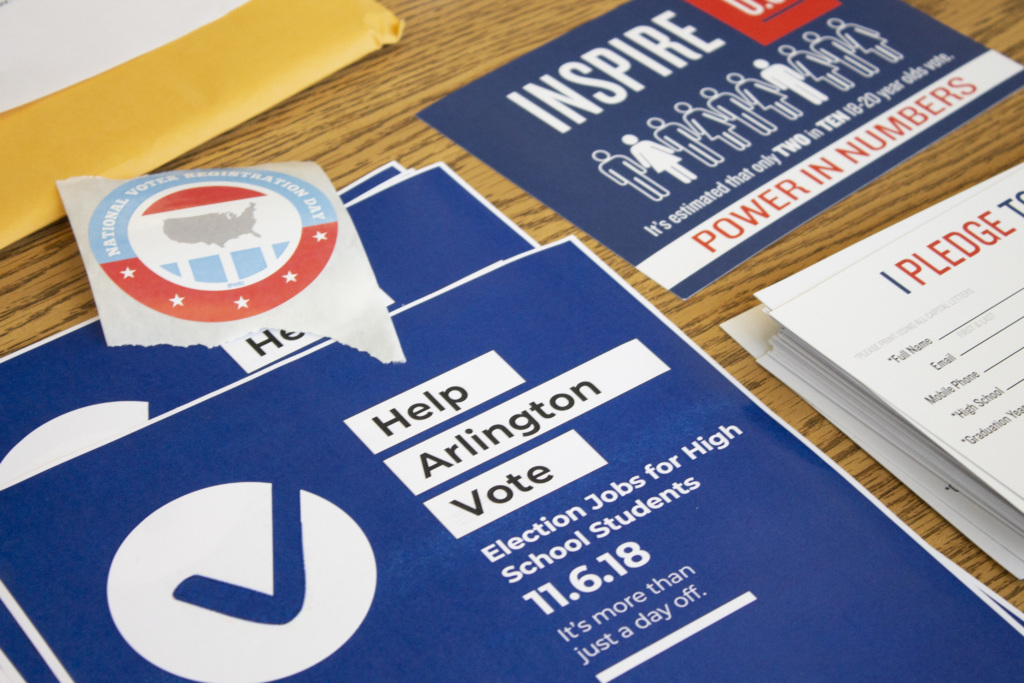

Civic engagement in action: A voter registration table, hosted by the League of Women Voters, at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia.

As civics education is increasingly part of the national conversation, and as school districts and state legislatures increasingly call for more of it, we need to have a good understanding of what civic engagement looks like for young people in the 21st century. How many civic actions from previous generations remain unchanged? How many have been affected, in both good ways and bad, by the enormous technological changes of the last two decades? And what new forms of civic engagement do we need recognize, refine and support in the classroom?

NLP’s approach to civic engagement consistently builds on news literacy as a foundation. After all, credible information is the very basis for civic literacy and engagement; it is what drives meaningful civic actions. If we don’t have that foundation, misinformation can cause people to take actions that are civically disempowering — not in their interests, or in the best interests of the republic.

Here are 10 important indicators of civic engagement that we’ll be discussing over the coming weeks (these assume that students already have the key skills needed to navigate today’s information landscape):

10 Indicators of Civic Engagement

- Pay attention to and understand how misinformation spreads on social media and debunk misinformation or false comments in a constructive, responsible manner.

- Pay attention to, and understand, issues being debated locally, statewide or nationally.

- Participate in a discussion about politics or current events — in school, with my friends or family, or online.

- Cast a ballot in an election (when I’m old enough) as a well-informed voter.

- Pay attention to, and understand, issues relating to individual freedom of expression and protected speech in the United States and abroad.

- Contact a reporter or news organization by email, social media or phone.

- Pay attention to, and understand, ongoing discussions about journalism and the state of the news media, including press freedom in the United States and internationally.

- Document something in my community and share it with others.

- Question or engage in conversations with my elected officials by email, social media or phone.

- Volunteer or advocate for a cause, idea, mission-driven organization or political campaign — one that aligns with my personal beliefs, that I’ve researched and that I have a deep understanding of.

In the coming weeks, I’ll be posting more detailed explanations and examples of how to connect specific news literacy skills with these civic actions. Today, let’s start with the first indicator: Pay attention to and understand how misinformation spreads on social media and debunk misinformation or false comments in a constructive, responsible manner.

As students become more immersed in the news and other information that surrounds them, the more misinformation, hoaxes, viral rumors and propaganda they will come across. Critically evaluating what they read, watch and hear and identifying the various types of misinformation they encounter are critical news literacy skills. Once they can do this, they can take an active, constructive role in debunking misinformation.

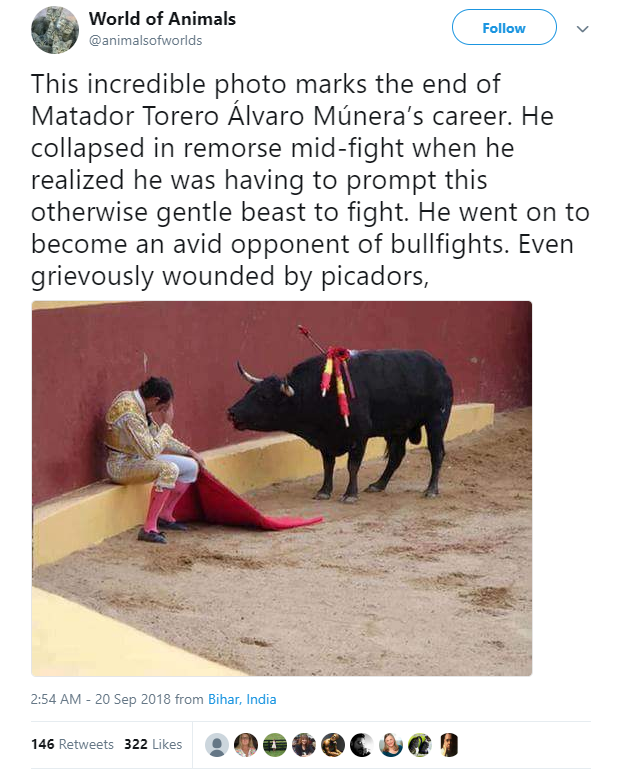

On Sept. 20, this tweet showed up in my feed:

To be sure, it’s a powerful image and message — one that animal lovers would readily agree with and quickly retweet. My critical eye thought that it was a little too perfect. There isn’t enough information in the tweet to provide credible evidence for what it says. When I scrolled through the replies, I quickly discovered that a few people had already called out the image.

I did a reverse image search and found two key articles debunking both the image and the explanation. It turns out that the photo is of a different bullfighter. In addition, what the bullfighter is doing is actually part of the act. As explained in the blog The Last Arena and confirmed by the fact-checking site Snopes.com:

“Sitting on the ‘strip’ around the ring after the sword has been placed in the bull is a known desplante, or act of defiance, within the part-scripted, part-improvised spectacle that is the corrida de toros.”

The bullfighter mentioned in the original tweet did eventually become an animal rights activist, but only after he was left permanently disabled after being gored by a bull.

This tweet reinforces the importance of reading through the comments or replies before retweeting. Others responded to it by sharing the same links I referenced above, tagging it #fakenews, calling out the original tweet for “harming the cause” or simply describing it as “utter tosh.” Yet some replied favorably, accepting the tweet as being true without checking further.

Some of the messages debunking the tweet were more effective than others — and the key to this civic action is teaching students the most effective ways to do this. In two published meta-analyses of studies about correcting misinformation from a variety of topics, researchers described strategies that are more effective at swaying beliefs and countering false information – along with those which are ineffective.

In their 2017 study, “Debunking: A Meta-Analysis of the Psychological Efficacy of Messages Countering Misinformation,” authors Man-pui Sally Chan, Christopher R. Jones, Kathleen Hall Jamieson and Dolores Albarracín made three key recommendations.

- Reduce the generation of arguments in line with the misinformation.

- Create conditions that facilitate scrutiny and counterarguing of misinformation.

- Correct misinformation with new detailed information, but keep expectations low.

If the debunking message includes arguments that are in line with the misinformation, it’s “difficult to eliminate false beliefs,” they wrote. The emphasis should be on the counter-argument or on the facts being used to debunk the misinformation — not on the original belief or false claim. Simply labeling the misinformation as being “wrong” or “false” also makes accepting the debunking message less likely.

Students should create a counter-message that is detailed and supported by facts — but don’t expect it to always work. The stronger someone believes misinformation initially, the harder it is to change their view.

A similar study, “How to unring the bell: A meta-analytic approach to correction of misinformation” by Nathan Walter and Sheila T. Murphy, highlights other factors to emphasize when debunking misinformation:

“Appeals to coherence tended to be best at correcting misinformation, compared to fact-checking and source credibility. In other words, providing alternative explanations that were internally coherent was more successful than providing ratings of the accuracy of specific statements or highlighting the credentials of a source.”

Relating to the recommendation of keeping expectations low, Walter and Murphy found that it was more difficult correcting misinformation relating to politics and science than misinformation in other areas, such as health, crime and marketing.

If you want your debunking message to be read loud and clear:

- Don’t just label something as “wrong,” “false” or “fake.”

- Don’t focus solely on fact-checking the content or source of misinformation.

- Make your message clear and detailed, and support it with facts.

- Emphasize an alternative explanation that brings clarity to the subject.

- Don’t expect everyone to readily accept your message.

People who pass on misinformation shouldn’t feel as if they are being personally attacked. In a way, a good debunking message is one in which those who shared a falsehood feel as if they came to the right conclusion by themselves — with a little nudge from you.