Education can solve ‘dueling facts’ phenomenon

The conclusions that political scientists Morgan Marietta and David C. Barker reach in their new book, One Nation, Two Realities: Dueling Facts in American Democracy, are enough to make the reader despair.

Based on data from national surveys conducted from 2013 to 2017, they determined that “dueling fact perceptions are rampant, and they are more entrenched than most people realize.”

In an article published May 8 on the NiemanLab website, the authors noted that, according to their findings, Americans no longer agree on basic questions of fact and often cling to beliefs that align with their values, regardless of evidence to the contrary. And fact-checking by reliable organizations appears to have little success in correcting people’s erroneous views. “This has serious implications for American democracy,” they warned.

I couldn’t agree more.

However, I think that Marietta and Barker are mistaken in their bleak prognosis: “Perhaps the most disappointing finding from our studies — at least from our point of view — is that there are no known fixes to this problem.”

The fix

There is no denying that today’s complex information ecosystem challenges all of us, but I believe that there is a fix to the problem: news literacy education. News literacy must be embedded in the American education experience. Nothing less than the health of our democracy is at stake.

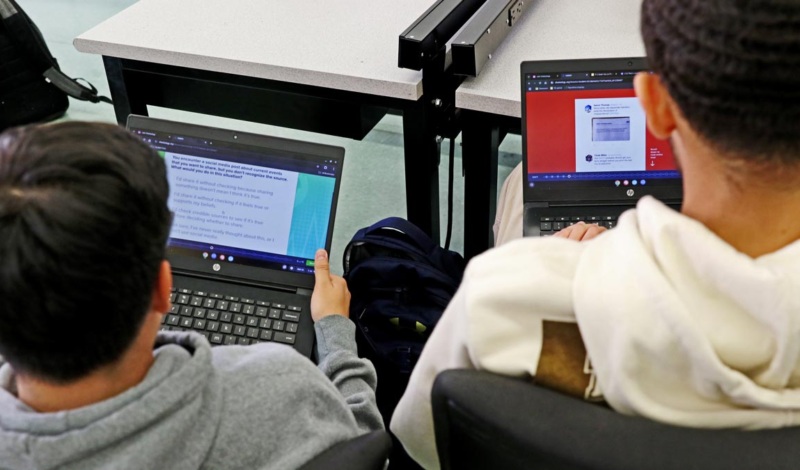

As the founder of the pioneering News Literacy Project, I have seen how real-world news literacy lessons can empower middle school and high school students. The Checkology® virtual classroom, our e-learning platform, reaches them as they are forming the habits of mind and the patterns of content consumption and creation that will last a lifetime, and it does so where they live — online.

The value of these newfound and lasting news literacy skills has resonated with Judy Bryson, a library media teacher at Wilmer Amina Carter High School in Rialto, California. “If students are going to advocate for themselves and become empowered citizens, they need to know where to find quality, trustworthy information,” she said, adding that Checkology has helped her integrate library and research skills into a variety of subjects.

Meaningful engagement

The platform’s relatable examples engage students in meaningful ways. They begin by learning to identify types of information based on its primary purpose (to inform, to entertain, to persuade, to provoke, to sell or to document) and then review examples of content and assign them to the correct categories.

In another lesson, students take on the role of a reporter covering a breaking news story. They learn the importance of evaluating sources, weighing witness accounts, paying attention to attribution and recognizing how the standards of quality journalism come into play. Other lessons explore how to assess the authenticity of photos and videos and determine the credibility of memes and viral hoaxes.

In short, students learn to think like journalists: After all, in the digital age, anyone can be a publisher, and everyone must be an editor.

Critical thinkers

Checkology doesn’t just impart specific news literacy skills; it helps students become critical thinkers. They learn to approach information with equanimity, not emotion; to value credibility, not clickability. This deliberative mindset will serve them well through a lifetime of informed decision-making.

Educators see how transformative this can be in their classrooms — and beyond.

Nicole Finnesand, a middle school language arts teacher in Colton, South Dakota, said that Checkology has provided a framework for her deeply polarized class to have constructive and civil discussions about current events and political issues. Students now come to class armed not just with opinions, but with facts and legitimate sources. (As an example, they no longer cite The Onion’s satire as the basis for their arguments.)

David Teeghman, who spent several years teaching at a Chicago high school, said the platform helped him inoculate his digital journalism students against conspiracy theories and manipulated or fabricated content. He recalled seeing one of his former students post a falsehood on Facebook. Before Teeghman could respond, other former students jumped in to respectfully call it out.

Empowered students

Students immediately begin to apply these lessons in the real world.

Valeria Luquin, a ninth-grade student at Daniel Pearl Magnet High School in Lake Balboa, California, said that her father had recently told her about a documentary he had watched. “Are you sure that the sources and the documentary are credible?” she asked him. She said the ability to think critically about the media “is really helpful and important, because nowadays, with social media, there can be a lot of fake news.”

Sophia Fiallo, now a 10th-grader at The Young Women’s Leadership School of Queens in New York City, said her news literacy skills kicked in last year when a friend shared a photo of Emma Gonzalez, a student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, tearing up the U.S. Constitution. Fiallo discovered that it was a doctored photo of Gonzalez ripping a shooting target as a protest against gun violence. “It didn’t come from a reliable news source,” Fiallo said.

Ultimately, we want students to recognize that they can be part of the information solution, rather than part of the misinformation problem.

Daniela Rangel, one of Luquin’s classmates at Daniel Pearl Magnet High School, exemplifies this goal. “I like to help people in whatever way I can,” she said. “So if that means telling them that they should try to find correct information over what they are seeing on social media, then that’s good.”

Besides, she added, “I think my parents take me a little bit more seriously. Why? Because I’m more literate, and I sound professional now.”