Early news literacy ‘lessons’ benefit Washington Post reporter

When Shane Harris, an intelligence and national security reporter at The Washington Post, was in fourth grade in the mid-1980s, he received an informal introduction to news literacy.

As part of his language arts and English class, Harris and his classmates spent a week learning how to read the newspaper. They started with the front page, as the teacher explained how stories placed there were likely the most important of the day. Then they turned to the opinion pages, learning the difference between columns and news stories.

“That is basic news literacy,” Harris said recently, “and it kind of informed a lot of my behavior as a news consumer ever since.”

Harris has reported about intelligence and national security for two decades and is the author of two books: The Watchers: The Rise of America’s Surveillance State and @War: The Rise of the Military-Internet Complex. He’s also a firm believer in news literacy as a solution to today’s convoluted information landscape. So Harris quickly jumped on board when the Post’s executive editor, Marty Baron, told the newsroom about the News Literacy Project’s Newsroom to Classroom program , which connects journalists with students.

“I was just really pleased that as an institution, we were encouraging our reporters to go talk to young people about how to read the news and how to be smarter consumers about it,” Harris said.

Connecting Washington Post, classroom

Once he signed up, Harris, who lives in Washington, D.C., connected with Cade Elkins, a high school teacher in Huntington, West Virginia. Initially, the session was going to take place over Skype with Elkins’ students in the room to ask questions of the journalist. But then COVID-19 hit and the school went remote. Elkins solicited questions from his students and presented them to Harris during an insightful, hour-long video conversation.

You can watch it here.

Harris was not surprised that the students asked pointed questions. He said he always enjoys speaking with young people, because they think of topics he’s not normally asked in everyday conversations about his job.

Harris was not surprised that the students asked pointed questions. He said he always enjoys speaking with young people, because they think of topics he’s not normally asked in everyday conversations about his job.

“They tend to ask like really frank questions that oftentimes go to just core basic issues about what we do, how we do what we do,” Harris said. “And I was also really impressed that they were clearly discerning. They had skeptical questions, too, about how we report and what they read and what they see.”

Elkins and Harris talked at length about an issue that Harris sees as critically important to having an informed public that trusts standards-based reporting — demonstrating how quality journalism is done.

Lifting the curtain on journalism

“I think that sometimes we hide behind the mystique of what we do to kind of convey some level of authority to it of, ‘Just trust us, we’re professionals,’” Harris said. “Well, you know, to a degree, yes, we’re professionals, but that doesn’t mean we’re above explaining how we do things to people.”

That’s a big part of what the Newsroom to Classroom program — and our NewsLitCamp® — are all about. If students have a better understanding of how reporting works and that a story doesn’t start and end in a day but develops over time, Harris noted, they will be more likely to trust good reporting and believe in its importance.

Journalists also can gain trust by helping students — and the general public — understand that they are doing their jobs to inform readers and are not insiders armed with special information that they choose to disclose based on personal motivations.

“I think the more that we can convey to people that what we do is a job and that we’re moving through the world just like everybody else, it makes it seem, I hope, that what we’re doing is more trustworthy and certainly more transparent,” Harris said.

News literacy a must

In high school, Harris’ favorite class was civics. He loved learning about government. But a lack of civics knowledge and education is a problem in the U.S. Almost half of adults questioned about civics couldn’t name all three branches of the government, according to the 2020 Annenberg Constitution Day Civics Survey. Given that reality and the immensely challenging information landscape, Harris thinks news literacy is a must for students and the public.

“We’re talking about basic tools that you have to equip people with not just to be good citizens participating in a democracy, but to ensure that they’re not exploited and they’re not taken advantage of,” he said. “I feel really strongly that news literacy is an important part of that kind of curriculum.”

The Newsroom to Classroom program is part of the solution.

If you are a teacher signed up for Checkology®, reach out to a journalist in the directory. If you are a reporter interested in talking about your profession to students, learn more about the program here.

Free news literacy resources for the public

Since 2008, NLP has helped students across the U.S. and beyond learn to sort fact from fiction. Now, to meet the urgent need for news literacy among people of all ages, we are unveiling free tools and resources for the public. This includes a customized version of our signature e-learning platform, Checkology®.

This expansion of our mission comes in response to the growing crisis of false information in America.

“We believe misinformation and a lack of news literacy skills and knowledge pose an existential threat to our democracy,” said Alan C. Miller, NLP’s founder and CEO. “We recognize the critical need for people of all ages to have the ability to determine what news and information to trust and to understand the importance of a free press as informed and engaged participants in a democracy.”

News literacy lessons for all

We have developed a version of Checkology that provides the public with a comprehensive news literacy program. And it is now available at no cost. Launched in 2016, Checkology is widely used by educators to teach middle and high school students news literacy skills, habits and mindset.

This new public version includes foundational lessons, supplemental practice opportunities and fact-checking tools for reverse image searches, geolocation and more. In addition, it teaches users how to identify credible information, seek out reliable sources, understand media bias — as well as their own. It also helps users learn to apply critical thinking skills to differentiate fact-based content from falsehoods. And users gain an understanding of the importance of the First Amendment and the watchdog role of a free press.

Learn more by watching our video:

New podcast

And today, we launched the podcast Is that a fact?, featuring experts who address the question, “How can American democracy survive and thrive in our toxic information environment?” The first episode, featuring writer and professor Brendan Nyhan of Bright Line Watch, is available on our website and on various podcast platforms. Upcoming guests include Kara Swisher of Recode and The New York Times, Maria Ressa of Rappler and Michael Luo of The New Yorker.

The 10-episode season is hosted by Darragh Worland, NLP’s vice president of creative services. The show will include conversations with leading American thinkers, journalists, foreign policy experts, psychologists and authors. It will seek to help listeners understand how they can become part of the solution to the misinformation crisis. Future segments will drop every Wednesday.

Additional resources

Also, starting Tuesday, Sept. 22, we will publish a free weekly newsletter for the public called Get Smart About News. This publication is adapted from our popular free newsletter for educators, The Sift®. It will highlight and debunk timely examples of the most widespread conspiracy theories, hoaxes and rumors. Readers will find tips and tools to help navigate today’s complex information landscape. Get Smart About News will arrive in subscribers’ inboxes every Tuesday.

Finally, in 2019, we launched a free mobile app Informable®. Updated in 2020 to address COVID-19 misinformation, Informable helps people of all ages practice four distinct news literacy skills in a game-like format using real-world examples.

PSAs to help voters learn to navigate election misinformation

NLP and The Open Mind Legacy Project (OMLP) released public service announcements today to educate voters on how to avoid being misinformed about the November elections. Comcast, The E.W. Scripps Company and public media stations will air the video and audio PSAs, which also will be featured in a paid and organic digital ad campaign on social media and other streaming platforms.

As the election approaches, misinformation and disinformation about the voting process by both domestic and foreign sources have the potential to undermine the democratic process. U.S. intelligence officials have issued warnings that other countries are already using such tactics to sow confusion and interfere in the election.

The initiative aims to prevent voters from being misled by false information, such as being told that they can vote by text or by phone, that the election is canceled or that polling places are closed or have been moved.

PSAs in English and Spanish

The PSAs include four 30-second and two 15-second videos in English and Spanish, as well as audio versions of the spots. They will debunk myths about voting, address the need for voters to break out of their filter bubbles and advise them to verify facts before sharing social media posts. The PSAs will drive viewers to a special webpage created to help the public understand how misinformation can influence elections. The page will include real-time examples of falsehoods, free resources for the public, blog posts with tips on understanding election-related data, downloadable graphics that show people how to identify misinformation, and quizzes and other tools to help build news literacy skills in the weeks leading up to the election.

The PSA campaign will focus on communities targeted in previous election-related misinformation campaigns that remain vulnerable to voter suppression tactics, including Black and Latinx populations. The effort is expected to reach millions of Americans.

You can watch and listen to the spots here. Anyone interested in airing them can download them or contact NLP for more information at www.newslit.org.

About The Open Mind Legacy Project

The Open Mind Legacy Project, a civic education and media nonprofit, produces The Open Mind, a weekly public affairs broadcast and daily podcast, supporting fact-based discourse, deliberative democracy and engagement of ideas.

Making sense of data: How to be savvy about data in the news

Making sense of data: How to be savvy about data in the news is is the conclusion of a series, presented by our partner SAS, exploring the role of data in understanding our world. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

Data is one of the best ways to understand our world, but it can also be one of the most challenging things to get right. Over the course of this series we’ve looked at the power and shortcomings of data and data visualizations. If you aren’t paying close attention, data easily can be used to mislead you. Common areas of concern arise in each step of data collection, analysis and presentation. Additionally, data can also be misleading in infographics and social media, two increasingly popular ways people are exposed to data. But, with this series and more practice, you can feel more confident about the way you are exposed to and consume data.

As we all experience increased exposure to media and data-driven messaging, we need to stay vigilant in how we read and respond to those messages. So, here are the top six takeaways from this series on how to be a savvy data consumer:

Be a critical thinker

What is the author trying to convey with the data? Does the data match the argument? Is more information needed to better understand the data?

Go beyond the numbers and search for context

Also, where did the numbers come from? What exactly does each number represent? Gather all the information you can about how the data was collected and why to help you understand what it really means.

Ask and answer your own questions

So, what does the data make you curious about? Does it prompt you to want to learn more? Are you able to answer your questions with the data that’s been provided? Try doing your own analysis on the data and see what you find.

Check important chart elements

And remember to double-check the most important elements of the chart to see if the data visualizations may be misleading in any way. This includes checking the scale on both axes as well as legends and labels to ensure they match what you expect.

Look past design

Is the visualization you’re looking at focused more on being beautiful or on accurately presenting information? Focus your attention on the underlying data and not the visual elements.

Be skeptical of flashy messaging

Big, bold titles and messages can be misleading. Confirm whether eye-catching content really matches the data presented. Even when you see subtle mentions of the author’s conclusions, it’s good to double-check those, too.

And keep in mind that data is all around us. It’s not only important to be a savvy consumer of data but also to give data the context it deserves when presenting your own findings. Continue to think critically about the data you see and be sure to take a closer look if something appears misleading. With these guidelines in mind, you have the power to use data to better understand and describe the world.

Test yourself: Take our data quiz (here or below)!

Related articles:

- 6 Strategies for making sense of data in the media

- Diving into charts and graphs in the news

- Exploring statistics in the media

- Understanding complications with data collection

- Evaluating claims made from data

- Special look at issues with infographics

- Spotlight on data in social media

- Quiz: Can you make sense of data?

![]() About SAS: Through innovative analytics software and services, SAS helps customers around the world transform data into intelligence.

About SAS: Through innovative analytics software and services, SAS helps customers around the world transform data into intelligence.

Making sense of data: Spotlight on data in social media

Making sense of data: Spotlight on data in social media is the sixth in a series, presented by our partner SAS, exploring the role of data in understanding our world. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

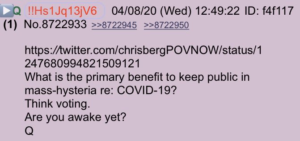

Like infographics, social media and other forms of user-generated content pose unique challenges regarding data. Many news outlets and journalists have checks and balances in place to ensure that information reported (especially information based on data) is as accurate as possible. But those same checks and balances do not hold true for those creating and sharing content. Social media gives user-generated content a wider reach and greater influence than ever before. Sharing content on social media poses additional challenges. For example, it can be difficult to identify the original source, and consequently, its credibility. In this post we’ll examine common issues that arise with user-generated and shared social content.

Social media posts are often criticized for allowing users to share pieces of information without putting it in context. This is particularly problematic with data. While the numbers and charts may represent real information, the reader needs context to interpret information correctly. Readers may inadvertently share questionable charts or statistics because social media platforms make it easy to do so. Images of graphs and charts pulled from research articles can quickly be shared without citing the source. These images might then circulate widely without context.

Intended for sharing

Even thoughtfully designed charts and graphs taken out of context can be problematic, but what happens when content is designed specifically for social media? Authors of social content know that readers often prefer brief messages instead of a large amount of information. Knowing shorter content is more likely to quickly spread to a wider audience, authors may intentionally design their social posts with content that will catch the eye of the audience they wish to reach.

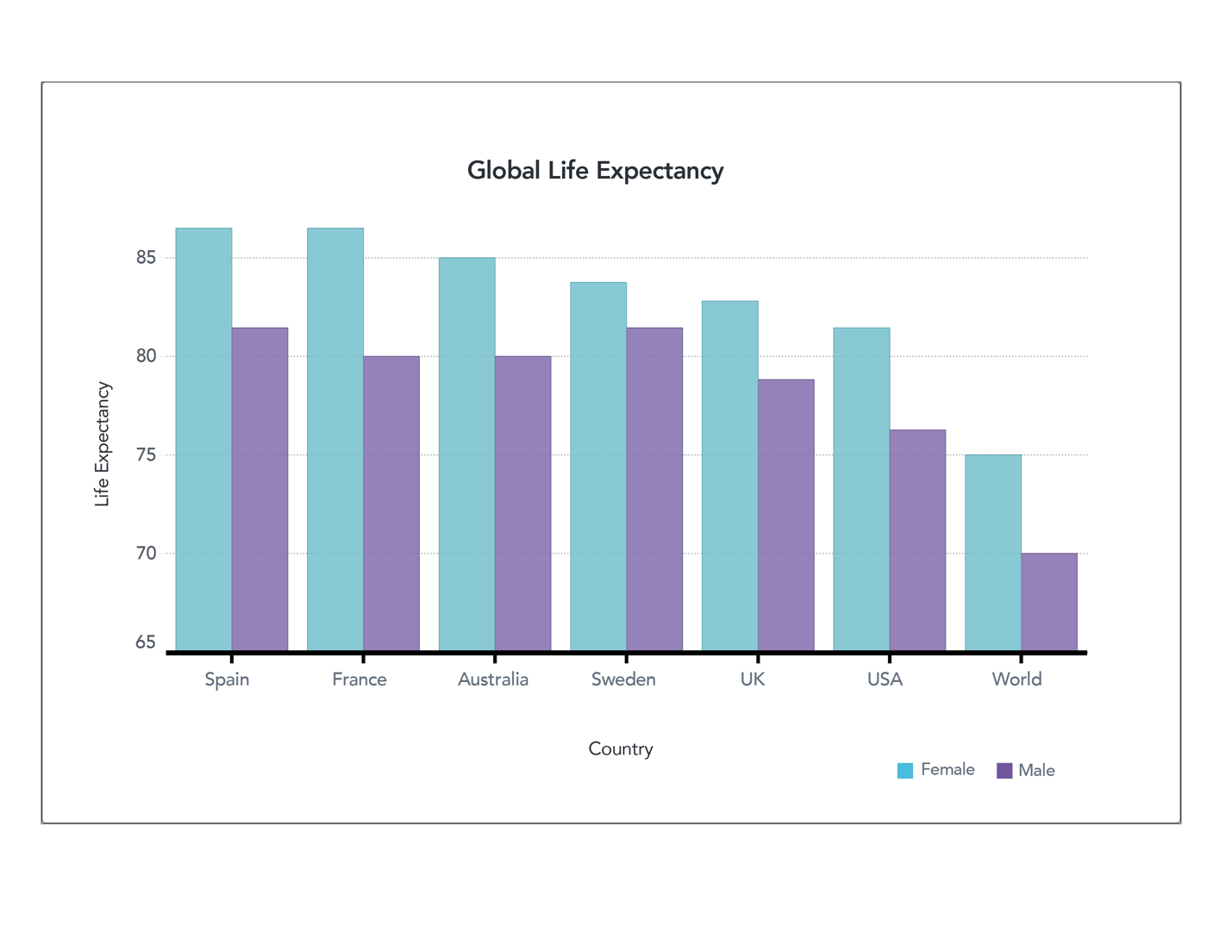

In earlier posts, we’ve discussed features that can make data and data visualizations hard to interpret correctly. Whether it’s logarithmic scales or truncated axes, we’ve seen how these may make data easier to read, but may unintentionally cause readers to draw inaccurate conclusions. While these mistakes are often unintentional, some users may intentionally manipulate visualizations to reinforce a specific point of view.

A fresh look

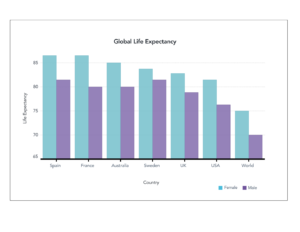

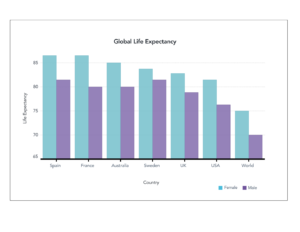

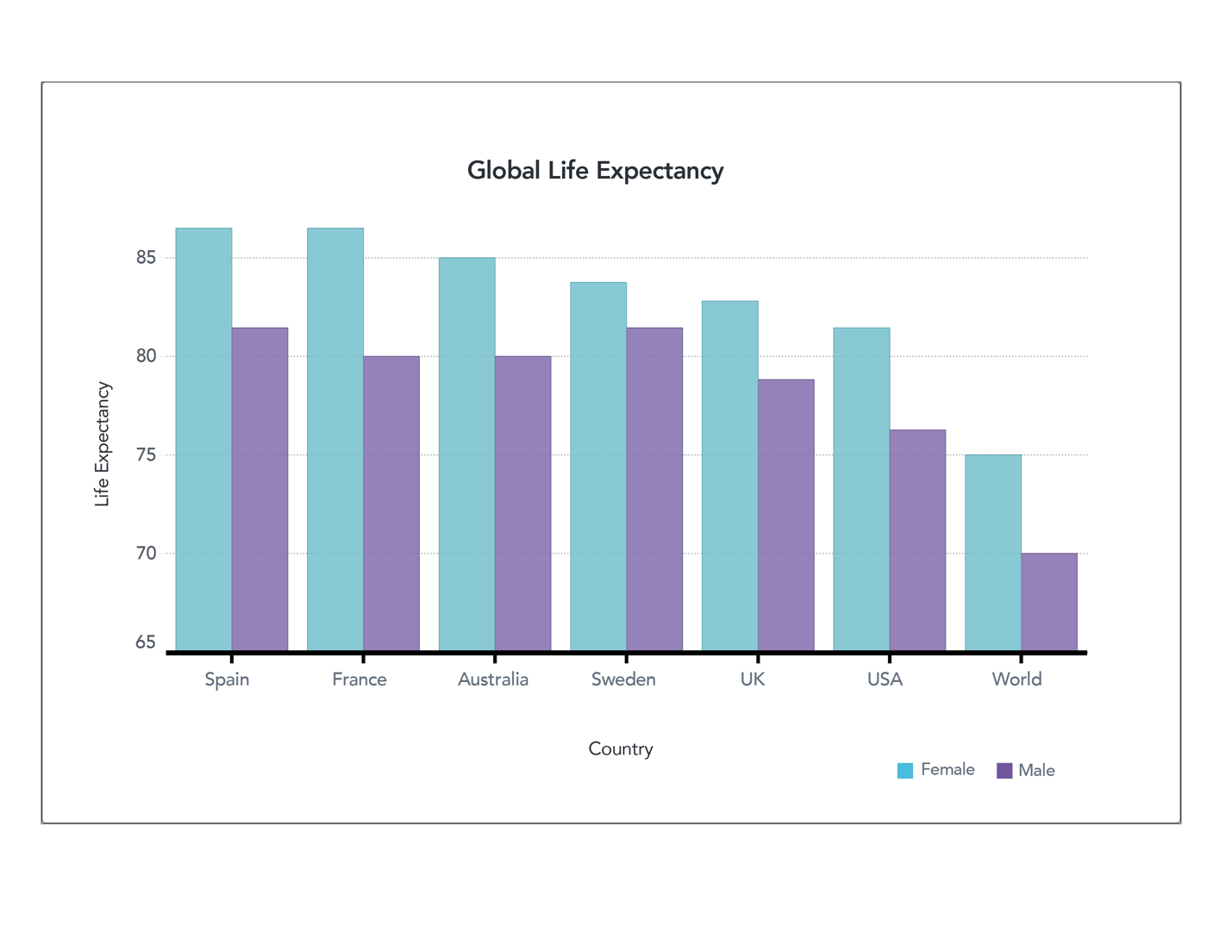

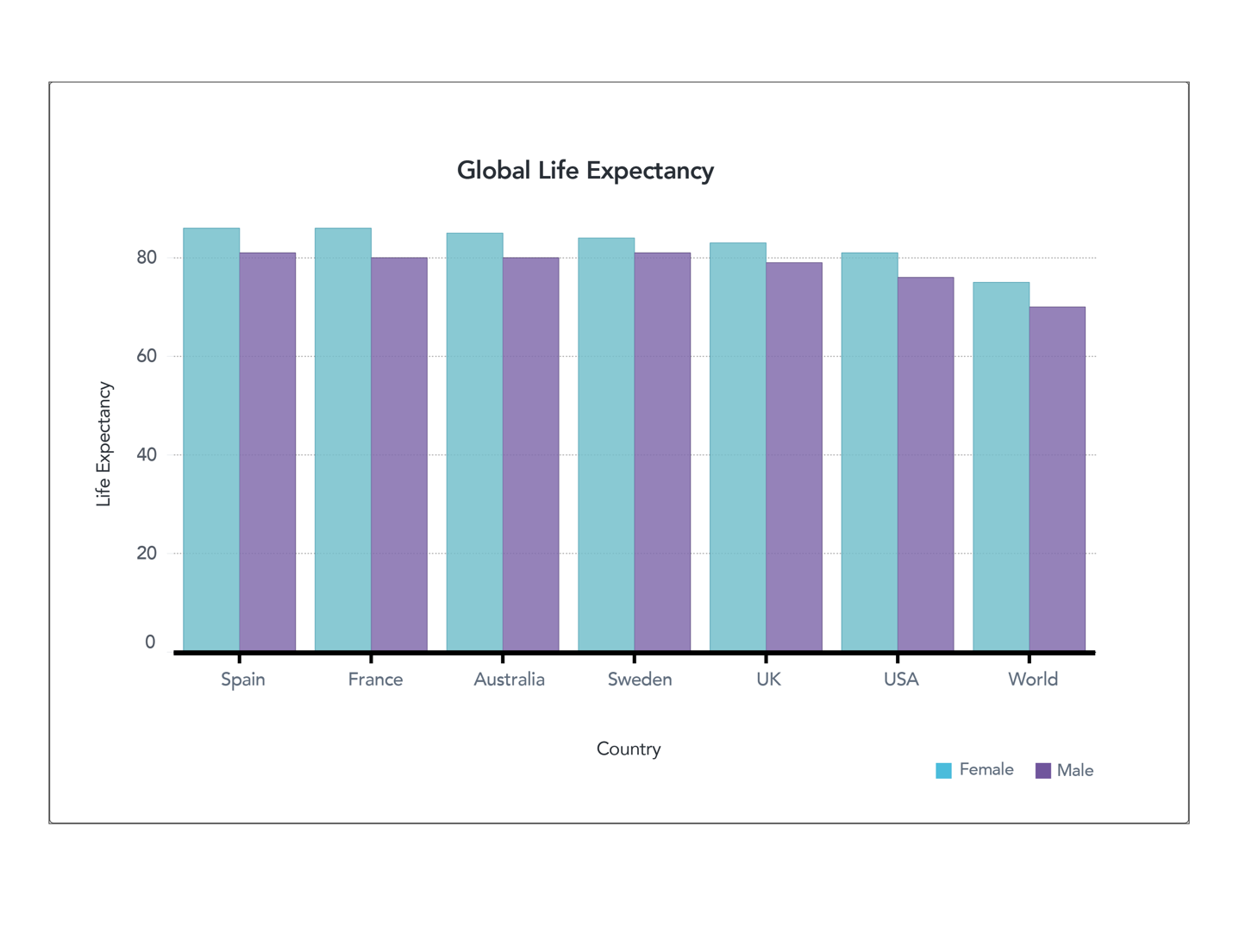

Figure 2. Global Life Expectancy (full axis) World Bank (male) World Bank (female)

Figure 1. Global Life Expectancy (truncated axis) World Bank (male) World Bank (female)

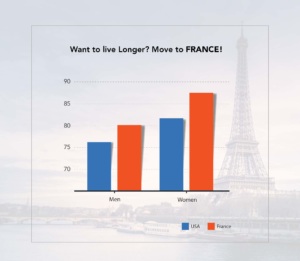

Let’s take another look at some of the data we examined before. These two charts show life expectancy in different countries. We demonstrated how truncating the axes allow you to see the differences in data, but also might lead readers to view those differences as more significant than they really are. Now suppose this isn’t an honest mistake, and the author wanted to create content to convince you of something – perhaps that you should move to France to live longer. If that were the case, the author might create a chart like the one below.

Does this seem like something you might see on your social media feed? The is the same data as in previous charts, but it’s been heavily manipulated so that you focus on what the author wants you to see. First, it includes a large title with the conclusion the author wants you to make – that moving to France will lead you to live a longer life. It doesn’t mention that this is solely the life expectancy of the country’s residents. A variety of cultural and lifestyle factors come into play, and would not apply if you simply move to a place. Also, removing gridlines and shrinking the size of the font showing age makes it harder to read the scale of the data. The choice of colors also further conveys the purpose — implying that the U.S. is worse than France.

Manipulating data to make a point

Let’s take a look at another chart. Here’s data from the same source, presented two different ways.

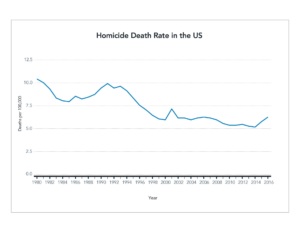

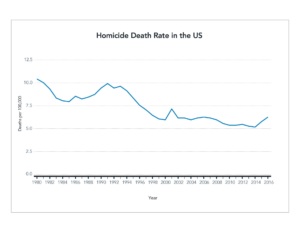

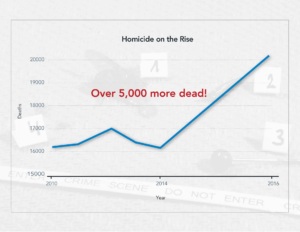

Figure 4. Homicide Rate Line Chart CDC

Figure 5. Homicide Rate Social Media Post CDC

The first shows the death rate by homicide relative to the population. It charts the rate over 36 years and indicates a mostly steady decline. Despite some bumps and dips, but overall, the trend is downward. However, look how the data can be manipulated to prove a specific point. The second graph uses a different unit, the raw number of homicides each year. It dos not average it out as population increases. The scale of years also is manipulated slightly. The first half of the graph represents four years, while the second half represents only two years. However, this isn’t brought to the reader’s attention. The axes are truncated, and the width is even reduced to further exacerbate the angle of the line. Again, the chart has a bold title with a random (and in this case meaningless) statistic tossed in for good measure.

There are many ways to manipulate data to prove a specific point. These graphs are just two examples of the ways people may present data to make a particular point, especially when sharing on social media. If you see a graph like the one above, with a catchy headline and no additional context, take a careful look and see if you can find how the author may have manipulated information to emphasize a point.

Disregard suspect data

It is challenging and sometimes impossible to conduct further research on social media posts or find the source or context of data presented. If you can’t find a reputable source that provides this context, it’s best to ignore the information. Approach it as an opportunity to be a responsible consumer of data — don’t share or “like” such posts! If you’re particularly curious about a point being made, see if you can find your own data to back it up and perhaps create your own content in a thoughtful, context-driven way.

To learn more see Diving into charts and graphs in the news or our full list of related articles below.

Test yourself: Take our data quiz (here or below)!

Related articles:

- 6 Strategies for making sense of data in the media

- Diving into charts and graphs in the news

- Exploring statistics in the media

- Understanding complications with data collection

- Evaluating claims made from data

- Special look at issues with infographics

- How to be savvy about data in the news

- Quiz: Can you make sense of data?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Making sense of data: Special look at issues with infographics

Making sense of data: Special look at issues with infographics is the fifth in a series, presented by our partner SAS, exploring the role of data in understanding our world. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

Infographics are one of the most visual ways to tell stories with data. They are designed to catch the reader’s eye, and they use visuals to provide a lot of information in a small amount of space. However, we’ve learned there are many ways data can mislead a reader, and those same issues often come up when using infographics. Let’s explore some of the special features of infographics that make these representations particularly challenging to interpret correctly.

Over-designing infographics

Infographics are intended to attractively display information and often incorporate several design elements. But sometimes those design elements overpower the data and distract the reader from the underlying information. Common design elements inspire the infographic below.

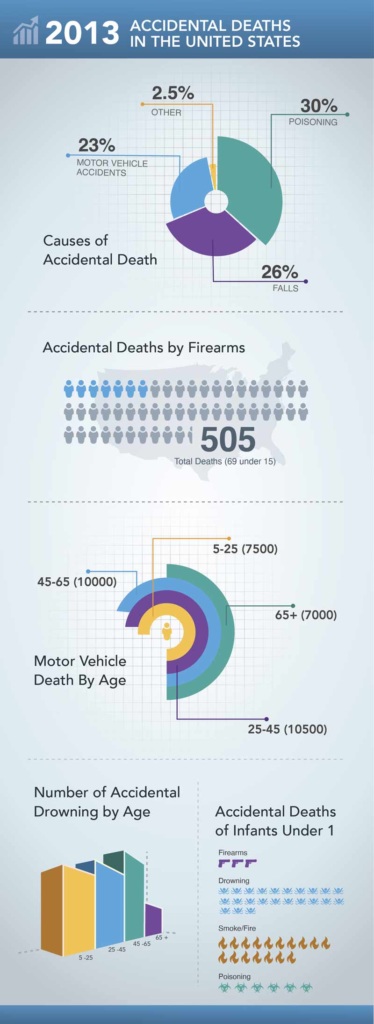

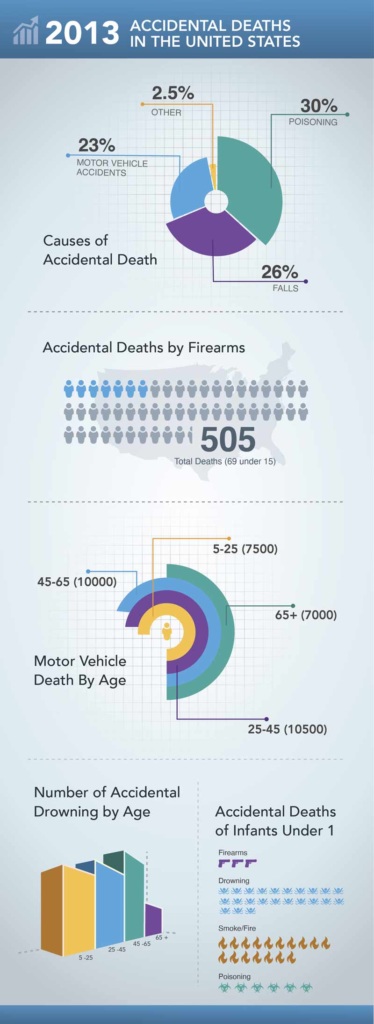

Figure 1. Example Infographic CDC

This infographic communicates facts regarding the causes of accidental deaths in the U.S. in 2013. The charts are designed to be visually appealing, and they are. However, the data itself could be communicated in a clearer and more concise manner if the creator used traditional graphs and charts.

Let’s start with the pie chart. It shows the main causes of accidental death. There isn’t much of a difference between the rates of poisoning (30%), falls (26%) and motor vehicle accidents (23%). Yet, the enlarged wedges imply that poisoning deaths far exceed deaths in motor vehicle accidents. This type of design violates the principle of proportional ink.

The next graphic shows a rounded bar chart depicting motor vehicle deaths by age. Here again, this type of display alters the perception of the data. Because the inner circle has a smaller radius, the yellow bar appears to go farther than any other bar. But if you look at the actual data, it should be much smaller than the purple or blue bars. The manipulation of the graphic makes it appear more significant than it is.

Consider size and scale

The use of icons to represent data, as seen in the chart showing accidental deaths of infants, is a common infographic design. However, if the creators aren’t careful, the size and scale of the icons can make the data difficult to accurately interpret. In this graphic, the drowning icon is smaller in scale than the others, hiding how many more deaths are caused by drowning compared to other causes. This graphic would be much easier to interpret correctly if the scale of the icons was equal.

The next bar chart, showing drowning by age, uses a different design treatment — a 3D view. This makes the chart more appealing than a traditional bar chart, but again, the design makes it harder to read. The 3D view doesn’t display axes so the only thing the reader can do is compare the different categories, not make judgments on the total numbers. The perspective on the chart is misleading as well. The scale of the first bar (ages 5-25) looks significantly larger than the last bar that’s further away (65+) but, the actual difference in these values is not substantial (710 and 554 respectively). This is another case where the design treatment of the graph makes it easy to draw incorrect conclusions.

The last graphic, accidental deaths by firearm, uses icons to communicate a statistic, but the graphic isn’t particularly helpful. Here each image icon represents 10 people accidentally killed by firearms, but the use of the graphic doesn’t help the user understand the scale of deaths. It is simply there to add visual display to a statistic.

Prioritizing design

In addition to the design issues above, important information may be left out of an infographic. The creator isn’t intentionally trying to mislead readers in this case, but rather, he or she is prioritizing design because the additional data might detract from the overall product. This can include important features such as axes, labels and other elements that are critical for reading and understanding a chart. Consider the 3D bar chart in our example. Without an axis labeling the value of those bars, it is impossible to interpret the chart accurately.

Context is often one of the most important things infographics can lack. We’ve talked in detail about the importance of asking questions about the data you’re reading, such as “what did the survey ask?” and “where does this data come from?” That information is often present in longer articles able to describe the methodology and sources of data. Infographics may not have this context to help you answer critical questions. A good infographic will provide at least a reference to where the data comes from, or where you can find more information, but this isn’t always the case. You may see infographics with data from a variety of sources, which means it may have been collected using different methodologies or samples, making it challenging to piece together a cohesive picture.

Overall, infographics can be a nice way to engage readers with data and information. However, issues arise when the design of the infographic takes precedence over accurately communicating information. Creators of infographics should carefully focus on readability first, before considering design. And readers should recognize that the issues we have covered about interpreting data in reports, articles and surveys hold true when interpreting infographics, and may be especially challenging in this case.

Test yourself: Take our data quiz (here or below)!

Related articles:

- 6 strategies for making sense of data in the media

- Diving into charts and graphs in the news

- Exploring statistics in the media

- Understanding complications with data collection

- Evaluating claims made from data

- Spotlight on data in social media

- How to be savvy about data in the news

- Quiz: Can you make sense of data?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Making sense of data: Evaluating claims made from data

Making sense of data: Evaluating claims made from data is the fourth in a series, presented by our partner SAS, exploring the role of data in understanding our world. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

Every day people use data to better understand the world. This helps them make decisions and measure impacts. But how do we take raw numbers and turn them into information that we can easily understand?

We make claims, or statements, about what we think the data tells us. And we often get our information from what the media report about data. And authors use data to support arguments or inform the public. However, the claims may depend heavily on how and what type of data was collected. We discussed some issues with data collection in the last post, but let’s go into more detail about issues that may arise when authors use data to build arguments or make claims.

Control or comparison groups

People often use data to draw comparisons between different types of groups or behaviors. It’s important to pay attention to the questions asked and who is being asked. And, it’s equally important to ask what researchers are comparing their claims against.

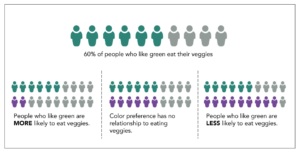

Imagine we poll people and find that 60% say green is their favorite color and they eat vegetables every day. We could claim that liking the color green means a person is more likely to eat vegetables. While the survey indicates that most people who like the color green eat vegetables daily, it’s hard to draw further conclusions without a comparison group.

If only 20% of people who don’t like the color green eat their vegetables, this might suggest an interesting relationship. However, it might also be true that 60% of people who don’t like green eat their vegetables – the exact same proportion. In this case, liking the color green has absolutely nothing to do with vegetable consumption. You might also find that 90% of people who don’t like the color green eat vegetables daily. This shows a negative relationship between liking the color green and eating vegetables daily.

As you can see, if an author presents only one number without comparison, interpreting the true value of the statement can be difficult. We need to compare that number against another group to get a better picture of its significance.

Learn more: Making Sense of Data on Checkology

Interventional studies

This is especially important when researchers conduct interventional studies in areas such as medicine, fitness, food, and other areas to investigate a particular outcome. In these cases, researchers use a control group. This is a special population that serves as a comparison and does not receive whatever is being tested. Designing an appropriate control group can be tricky because things can change simply because the group is aware it is being observed.

Imagine we conduct a trial for a new weight loss drug. Participants are split in half. One group receives the new drug, and the other group receives nothing. Our goal is to determine which group loses the most weight. It may be that the people who receive nothing realize that the situation remains the same and they are not receiving treatment. It’s unclear how this might affect their behavior. Similarly, the people taking the drug assume something might happen, and perhaps this affects their attitude and behavior. We can’t tell if the drug had the impact or if the act of taking a pill changed their behavior. For this reason, many studies include a placebo, a pill that doesn’t contain any chemicals at all, as part of the comparison. This works well especially if researcher and participants do not know who gets the placebo and who gets the real drug.

More challenging studies

This can be much harder in studies that don’t involve medication. Perhaps my intervention is an exercise program. How can I design a fair control group? Do I give my control group advice to not exercise? Do I ask them to do exercise that is similar to my program but not exactly the same? Each of these decisions directly impacts the comparisons I might be able to make and how I will communicate results.

When reading such study data, it’s important to look at the actions of both the experimental group and the control group. Ask yourself if the comparison seems fair, or if it seems as though one group had an advantage or disadvantage. What other factors might explain the results you see?

Bias in research

Finally, why the studies are being conducted and who is interested in the research are of particular concern in data and research studies. Specifically, organizations collecting data on their own products may be motivated to prove those products work or that people like them. They may unintentionally make decisions in designing their research questions or comparison groups that increase the chances they get the results they’d like to see. Researchers who receive money from a specific organization may also make decisions that favor the group that funded their research. As we’ve already learned, there are many complicated decisions that go into collecting data that will inevitably impact the quality of the final result, so it’s important to critically analyze these choices.

While data allows us to measure and better understand our world, it is not a perfect representation of reality. There are many opportunities for bias or flaws when collecting data that can impact the quality of the results. Critical thinking is the best way to find these biases or flaws when reading about data. Ask how the data was collected and from whom. Look for who was included and who was left out. If there is something that seems impressive, ask “compared to what?” To gather those answers, you may have to do some digging of your own, but it will help you determine what data you can trust and recognize data that may be too biased or flawed and should be disregarded.

Test yourself: Take our data quiz (here or below)!

Related articles:

- Six strategies for making sense of data in the media

- Diving into charts and graphs in the news

- Exploring statistics in the media

- Understanding complications with data collection

- Special look at issues with infographics

- Spotlight on data in social media

- How to be savvy about data in the news

- Quiz: Can you make sense of data?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Making sense of data: Understanding complications with data collection

Making sense of data: Understanding complications with data collection is the third in a series, presented by our partner SAS, exploring the role of data in understanding our world. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

As we have seen, statistics and visual representations of data can be misleading. But what happens when the data itself is misleading? And if data is supposed to be based on fact, you might wonder how data can be misleading. It comes down to the way it is collected. It is essential to have a strict process of collecting data before analyzing or presenting it. To ensure the data is accurate and as representative as possible, we must pay special attention to how data is collected.

Here are some of the most important questions to consider when understanding how data is collected:

- Who or what is represented in this data?

- What questions are being asked?

Sample selection and data collection

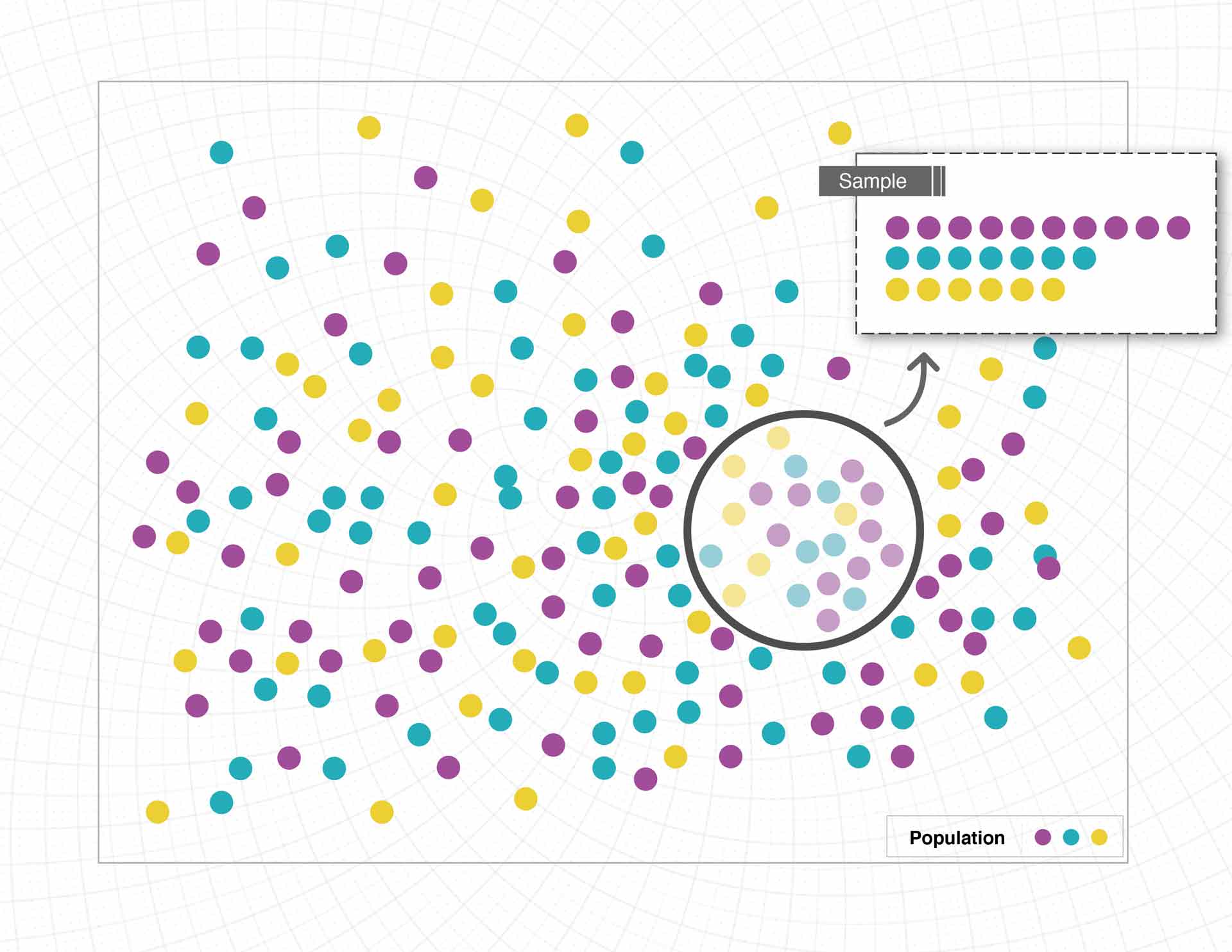

Without collecting data on an entire population, it’s nearly impossible to report it with complete accuracy because of sampling limitations. Suppose we want to better understand the eating habits of Americans. The only way to ensure we have an accurate picture of American eating habits is to monitor every single American, every second of the day, and record everything they eat. Since this is impossible, researchers will oft en use a sample, or a small portion of the population of interest. When the sample selected isn’t representative of the larger group, you get misleading data.

Consider how this might play out if someone was conducting a dietary study of Americans. In this case, the study asks 100 people about their eating habits. But how are those people selected? Options are endless:

- Collect data from 100 friends. That’s a convenient sample, but most people’s friends are about their age and eat similar types of foods.

- Gather data from a local restaurant or grocery store. Again, this might impact the type of data collected. For example, surveying people in a fast-food restaurant may give very different answers than surveying people in an upscale restaurant or a health food store.

- Conduct surveys at a non-food establishment, such as a library. This could be problematic, as library–goers might eat differently than the rest of the population. But even more concerning, those library–goers all come from the same area. The type of food people eat varies by locale. Those who live in cities likely eat different foods than those who live in rural areas. Food preferences can also vary depending on a person’s background or culture.

All of these are confounding factors or present possible issues with data. If we want a representative sample, we need to gather data from a cross section of age, gender, race, residence, income level, and so on. Finding such a representative sample can be incredibly difficult, and so it doesn’t often happen. Researchers typically report the population used in samples. This helps the reader understand who is reflected in the sample and the impact that might have on the results. As a consumer of data, it’s important to pay close attention to this piece of information. Ask yourself if the results presented by the researchers apply to the whole population or if those results only apply to the population sampled.

Additionally, there can be issues when how the data is collected, or the questions asked, only tell part of the story. We said before that the best way to see what people are eating is to consistently monitor what they do, but getting firsthand access to information like this is often impossible or unethical. Instead, researchers design studies or questions to gather similar information. Consider the following scenarios:

- Researchers ask participants to keep a food log for a week that details everything they eat and track total servings of fruits, vegetables, meat, etc.

- Researchers ask participants “In general how many servings per day do you have of fruits, vegetables, meat, etc.?”

- Researchers ask participants “What kind of foods do you usually eat?”

Each of these scenarios is trying to answer the same question: What do people eat? But the information is being gathered in very different ways.

Scenario 1 seems closest to our observation study, but there are some ways that the data may be biased. One concern is that people know they’re recording their foods, and this may lead them to eat differently for the duration of the study. The data could also vary depending on the time of year. Many people make different food choices in the summer compared to the winter.

Scenario 2 also presents problems. This question asks people to think more holistically but relies on memory and judgment. Individual estimates of what is typical may vary from what is actually eaten. People may intentionally or accidentally make themselves appear to be healthier eaters than they really are. It can also be difficult to accurately judge your own behavior.

In Scenario 3, the question isn’t specific enough to gather good information. While people might report the amount of fruits and vegetables they eat, the question leaves room for general or unrelated answers, such as cuisine type (Italian, Mexican or others), or a preference to eat out or at home.

As you can see, the way questions are asked, and who is asked those questions, makes a big difference in the kind of information collected. Some questions are better than others. When interpreting data, see if you can find the questions asked by the researchers. Are they good questions? And are the results influenced by how the researcher asked them or how they gathered the data?

Test yourself: Take our data quiz (here or below)!

Related articles:

- Six strategies for making sense of data in the media

- Diving into charts and graphs in the news

- Understanding complications with data collection

- Evaluating claims made from data

- Special look at issues with infographics

- Spotlight on data in social media

- How to be savvy about data in the news

- Quiz: Can you make sense of data?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Making sense of data: Exploring statistics in the media

Making sense of Data: Exploring statistics in the the media is the second in a series, presented by our partner SAS, exploring the role of data in understanding our world. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

“Numbers don’t lie” is a phrase we often hear to support the idea that something must be true if you can cite data or statistics about it. But even accurate numbers can paint a misleading picture, particularly if people don’t know what to look for. Several common ways to report metrics and statistics can easily mislead readers. Let’s explore how statistics can be misinterpreted.

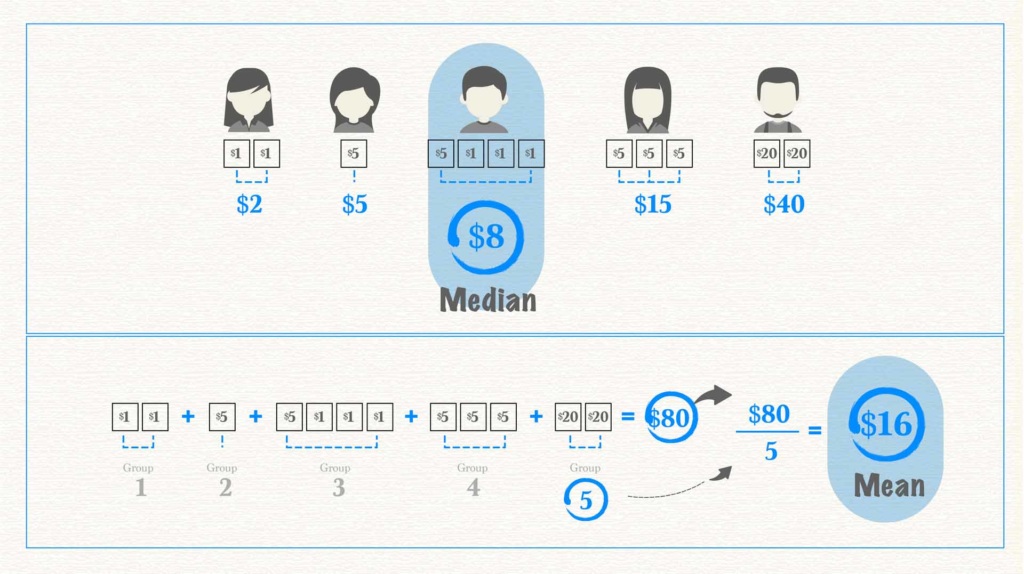

Mean vs. Median

Mean and median are two statistical concepts that often get muddled. Both are measures of central tendency, meaning the values are intended to represent the “middle” of the data. But this can be done in different ways, which is important to understand.

To find the mean, or average, add together the value for every member of a group and divide it by the total number of members. Say you and four friends were trying to figure out the average amount of money in your wallets. You’d count up the total amount of all your money and divide it by five. Median, on the other hand, represents the value in the very middle. In this case, you’d arrange each person’s money from the least amount to the greatest. The median is the amount in the middle. Two people have larger amounts, two people have smaller amounts. The person with the median amount of money is smack in the middle.

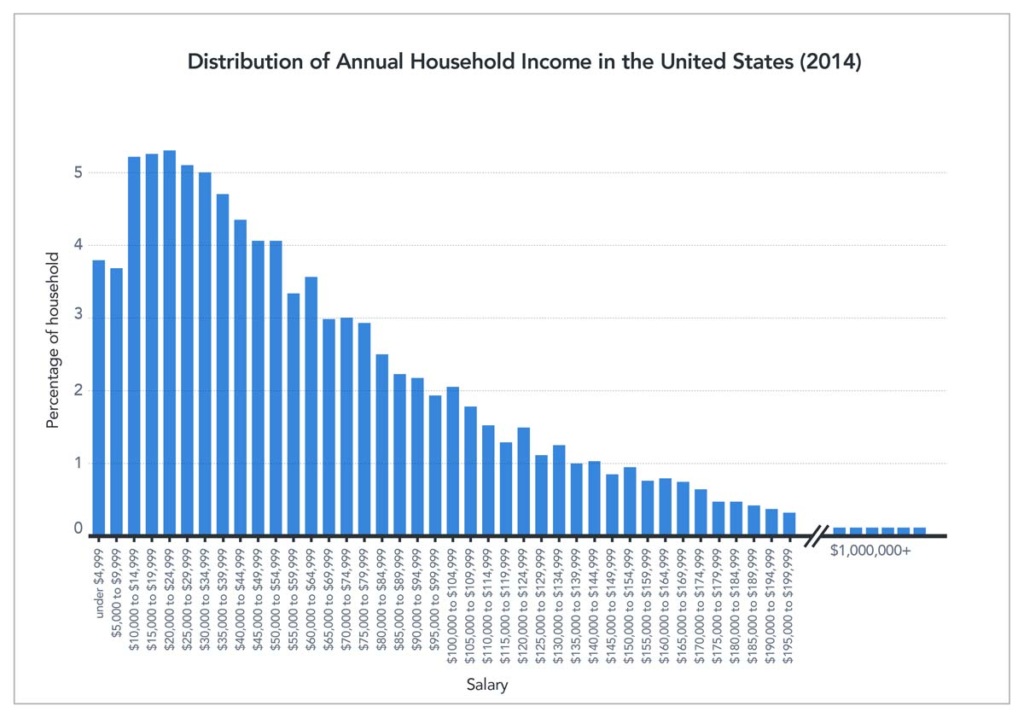

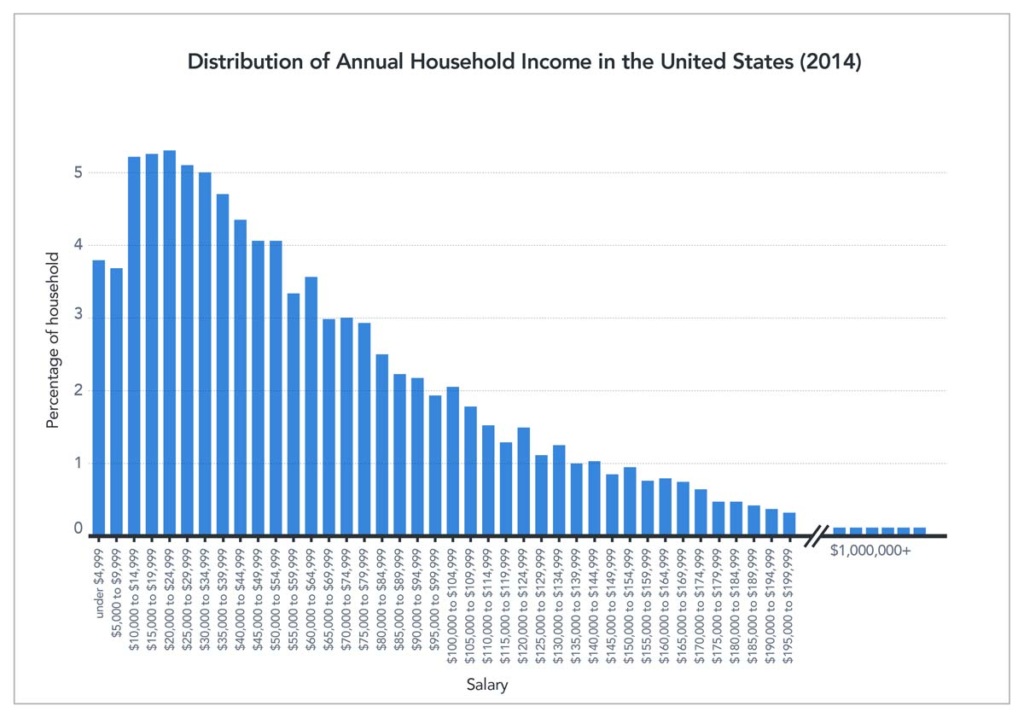

As you can see in the image above, the average and the median are not always the same. In fact, with heavily skewed data, they can be quite different. When we talk about skewed data, we’re referring to data with a heavy concentration of values on one end and only a few values on the other end. This often happens when discussing income, which is easily skewed because most of us have middle- or low-income levels while only a small percentage have very large incomes. Take U.S. income data from 2014, for example.

Figure 2. Distribution of Annual Household Income in the United States (2014) U.S. Census Bureau

Don’t be misled

The median income in the U.S. is approximately $33,000, while the mean (average) income is approximately $50,000. This data shows half the U.S. population makes $33,000 or less. However, if you consider the total of 2014 incomes across the population and divide by income-level breakdowns, the average salary is $50,000. This average salary might lead you to believe that the “average American” is doing better than he or she actually is. In reality, people who make the median salary would love the 50% raise the average salary represents. The value reported can make a big difference in how people understand information.

Impact on decision-making

A solid understanding of these metrics is especially important when statistics influence decision-making. Consider how life expectancy is often reported. Though we rarely see the term “average” used, that is what the data show. The average age at death in the U.S. is around 79, but the median age at death is about 83. This difference has a big impact on decision-making, such as retirement planning. It is quite different to say, “the average person dies at 79” compared to “half of adults live 83 years or longer.” Our retirement funds would likely be more of a priority in the second instance than in the first.

So, which measure is the best one to give when explaining data? Whenever possible, the answer is both. Knowing both mean and median gives the reader a better understanding and clearer picture of the data at hand and helps them draw accurate conclusions. But having people apply this thinking is not always in the best interest of the person reporting the numbers. You’ll notice that lottery tickets often advertise the “average winnings,” which can be enticing, compared to the “median winnings,” which are usually $0.

Percent Change

Changes, when given as a percentage, are another type of statistic commonly misused or misinterpreted, and can cause confusion.

One particularly confusing case arises when the value that is changing is, itself, a percentage. Suppose a local politician is performing “fairly well” with an overall approval rating of 50%. Then, this politician opposes a bill to fill all the potholes in town, and with that, the politician’s public approval plummets. If the politician’s approval rating dropped by 20 percent, that is 20% of the initial 50%, giving the politician a 40% approval rating. The narrative changes if the politician’s approval rating drops 20 percentage points. This brings the rating of 50% down to 30% — 20 points lower. The language sounds very similar but the resulting numbers are quite different.

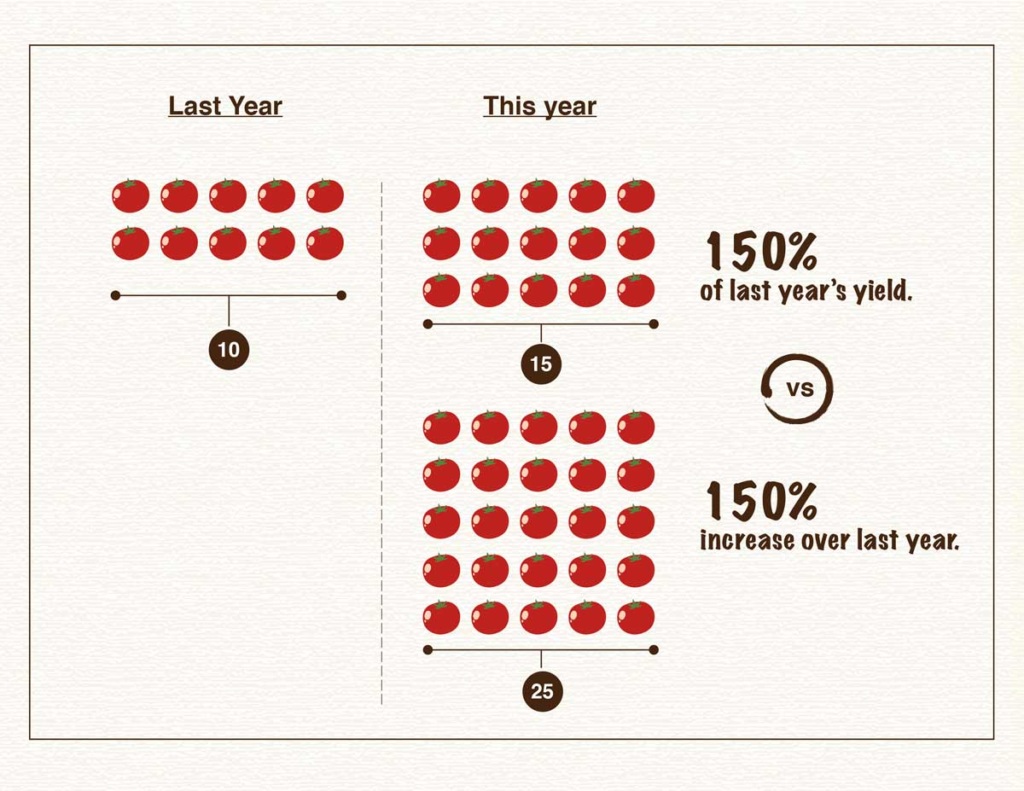

Another common source of confusion arises when something increases over 100%, or doubles. Imagine we’re talking about a garden and how many more tomatoes were grown this year compared to last. If 100% more tomatoes were grown this year compared to last year, that means the yield doubled — 10 tomatoes became 20. What if the yield went from 10 tomatoes to 15? The yield increased by 50%, but the total yield is 150% of the previous year. Confusing? Yes! That’s why statistics can be difficult to interpret.

Avoiding confusion

Sometimes authors confuse the two and report that something increased 150% when it only increased 50%. Say the garden produced 25 tomatoes this year, an increase of 150%. But someone might interpret that to mean the garden had 150% of the yield and only had 15 tomatoes. It’s often confusing, and when reading someone else’s reporting it can be hard to tell if the correct percentage is being cited since these terms are often and easily misused accidentally, or perhaps by design. If reporting an increase, an easy way to solve this problem and help the reader fully understand the metric being used is to provide all the numbers up front. One could report, “the garden’s yield increased from 10 to 25 tomatoes. That’s a 150% increase!”

Another tricky area when interpreting data involves the unit an author chooses to present. Sometimes, the same information can look very different depending on the unit presented. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic we’ve seen different sources report new cases, total cases and cases per capita, all of which have very different patterns of behaviors across states and countries. Authors also might talk about total deaths, deaths per capita or deaths as a proportion of positive cases. This post provides more detail about the differences these numbers represent and how those differences in reporting can impact how we understand data.

A significant influence

The types of statistics and metrics authors use to communicate data can have a significant influence on how information is interpreted, especially if the author is not careful to fully explain the reasoning behind them. Authors can also make mistakes when presenting and interpreting statistics because of nuanced differences in language and calculations.

To ensure you understand data you encounter, carefully consider whether the metric used is the relevant one, given what the author is trying to communicate. If you don’t feel it is, try to find more information about what might be missing. If you are presenting your own data, the safest route is to carefully explain the metrics being used and the motivation behind those metrics. Working through this explanation helps you as well, providing the opportunity to confirm you’re reporting information in the best way possible.

Test yourself: Take our data quiz (here or below)!

Related articles:

- Six strategies for making sense of data in the media

- Diving into charts and graphs in the news

- Understanding complications with data collection

- Evaluating claims made from data

- Special look at issues with infographics

- Spotlight on data in social media

- How to be savvy about data in the news

- Quiz: Can you make sense of data

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Making sense of data: Diving into charts and graphs

Making sense of data: Diving into charts and graphs is the first in a series, presented by our partner SAS, exploring the role of data in understanding our world. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

Charts and graphs are useful tools for communicating complex information. They allow consumers to see — rather than read or calculate — differences and trends. Charts and graphs provide readers the ability to visually consume information, answer their own questions and draw novel conclusions. Yet, these types of data visualizations are often designed to communicate the purpose of the creator. Those creators make decisions while designing charts and graphs to potentially emphasize characteristics of the data that lead users to draw specific conclusions.

Need an example? Let’s start with this chart showing life expectancy for males and females in different countries.

Figure 1. Global Life Expectancy (truncated axis) World Bank

This chart was specifically designed to highlight the differences among groups. It’s very clear that in all the countries selected, women outlive men by several years. We see that the high-income countries selected in this chart have greater life expectancy compared to the rest of the world, but people in the U.S. have a lower life expectancy than those in other industrialized nations.

If we examine the chart more carefully, we see that it violates the principle of proportional ink. This principle of data visualization recommends that the amount of ink used to represent values be proportional to the value it represents. This chart violates this principle with a truncated — or shortened — vertical axis that starts at age 65. When you look at the difference between male and female life expectancy across the world, twice as much ink is used for the female bar as for the male bar. If viewers don’t double–check the labels on the axis, this may inadvertently lead them to think that women are living twice as long as men. More likely, readers notice the labels but still perceive the difference as being very significant.

Figure 2. Global Life Expectancy (full axis) World Bank

Alternatively, the above chart represents the same data but follows the principle of proportional ink. The height of each bar is proportional to the value it represents. Here, the significance of the trends is visible but much less stark. We can again see that women outlive men and that the U.S. is a bit behind the rest of the industrialized nations, but this chart highlights that the differences are a matter of a few years and not a much higher order of magnitude.

If an author were trying to discuss the differences, you could imagine that this chart would be less compelling than the first. Neither is inaccurate; they just use visual cues to highlight different aspects of the data, which can lead readers to draw different conclusions.

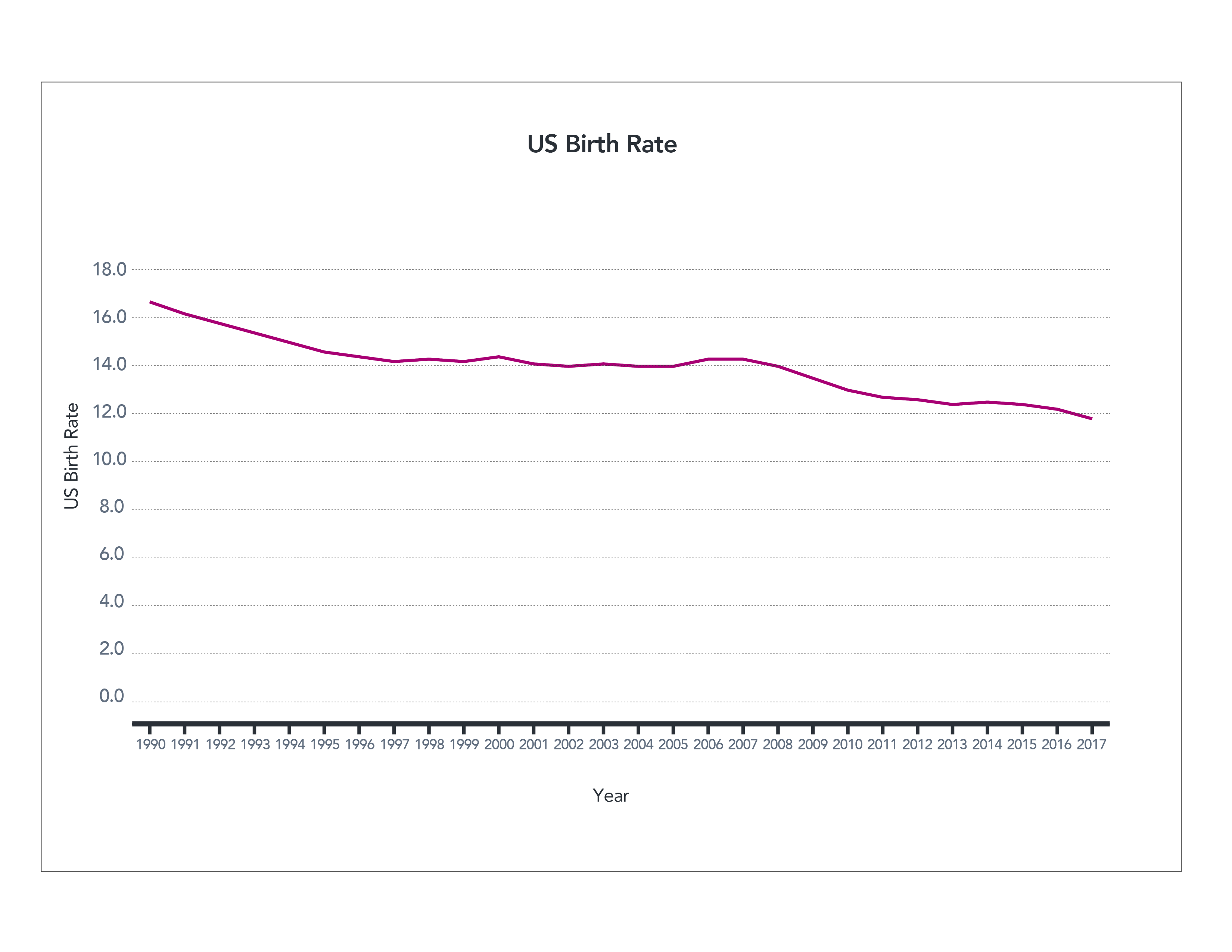

Looking at a line chart

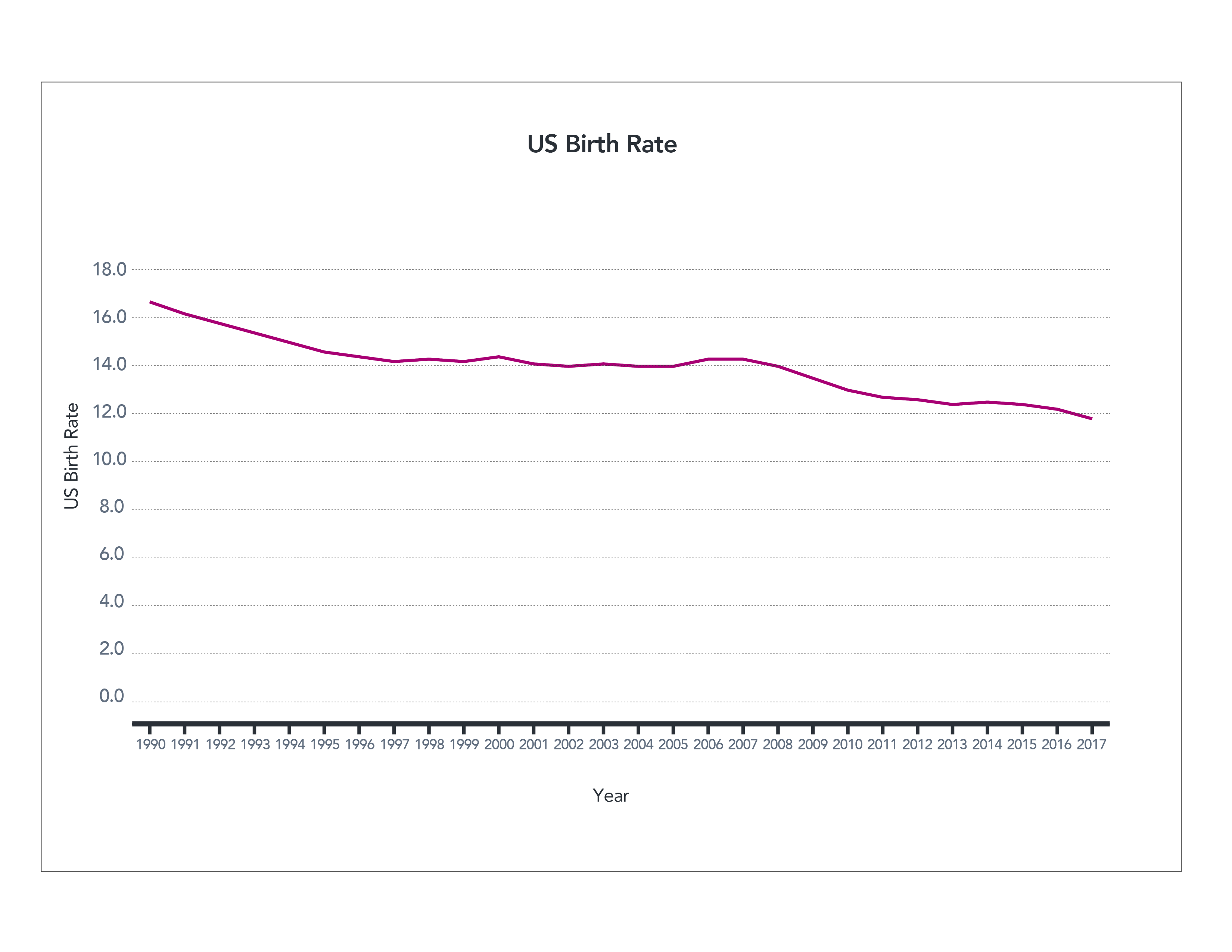

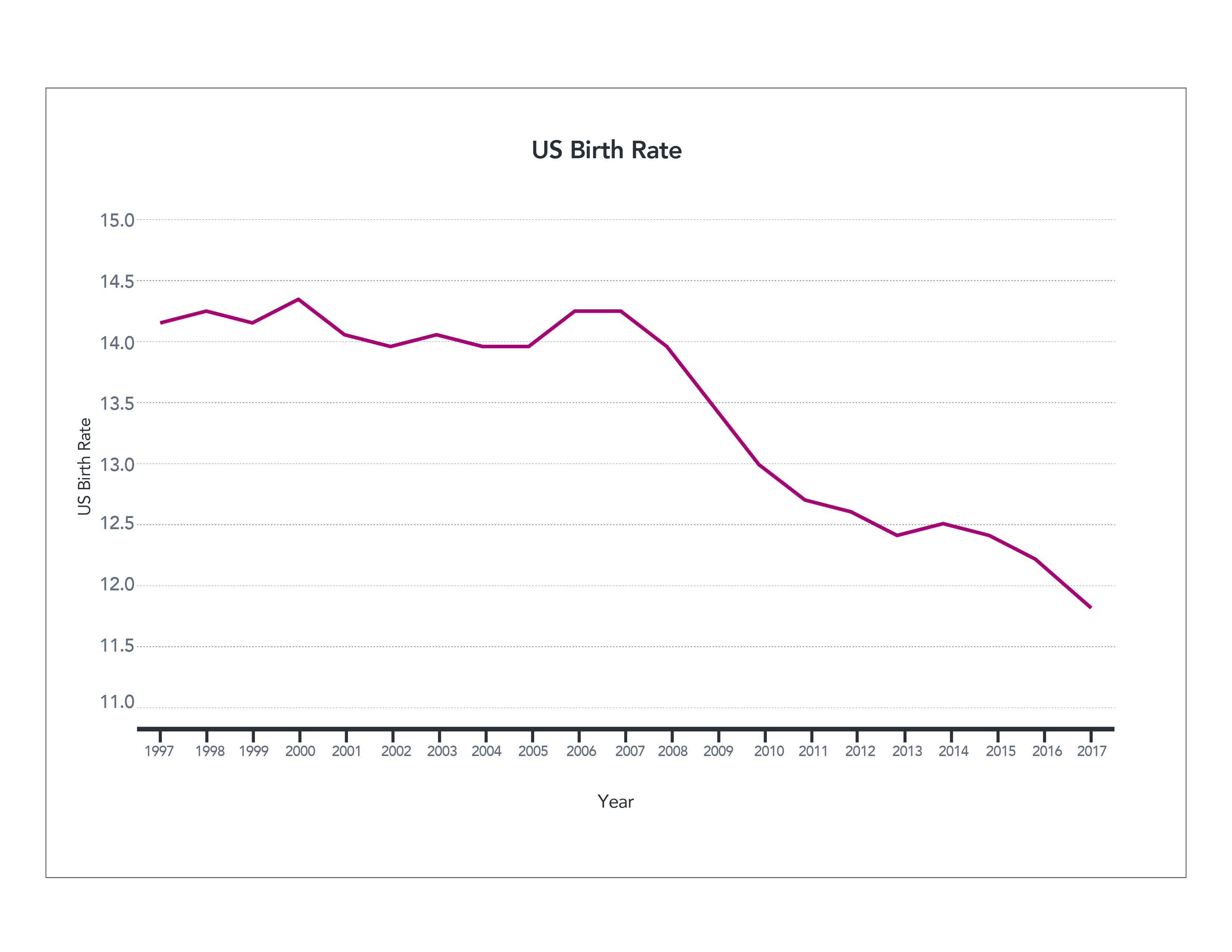

Let’s explore a different approach using a line chart. The chart below shows changes in the U.S. birth rate (births per 1,000 people) over time. This line appears to be moving slowly and steadily downward, representing a decline in births over time.

Figure 3. US Birth Rate (full axis) World Bank

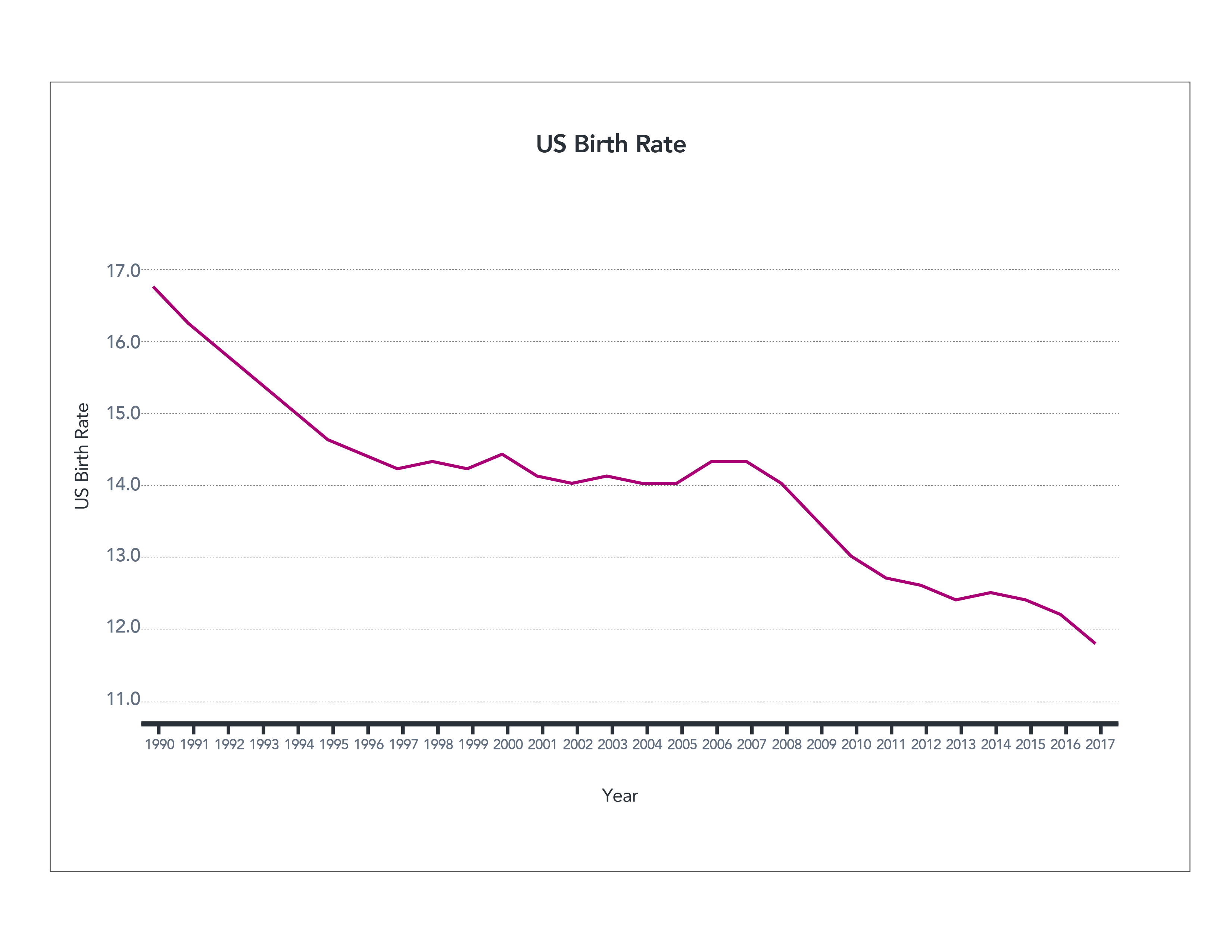

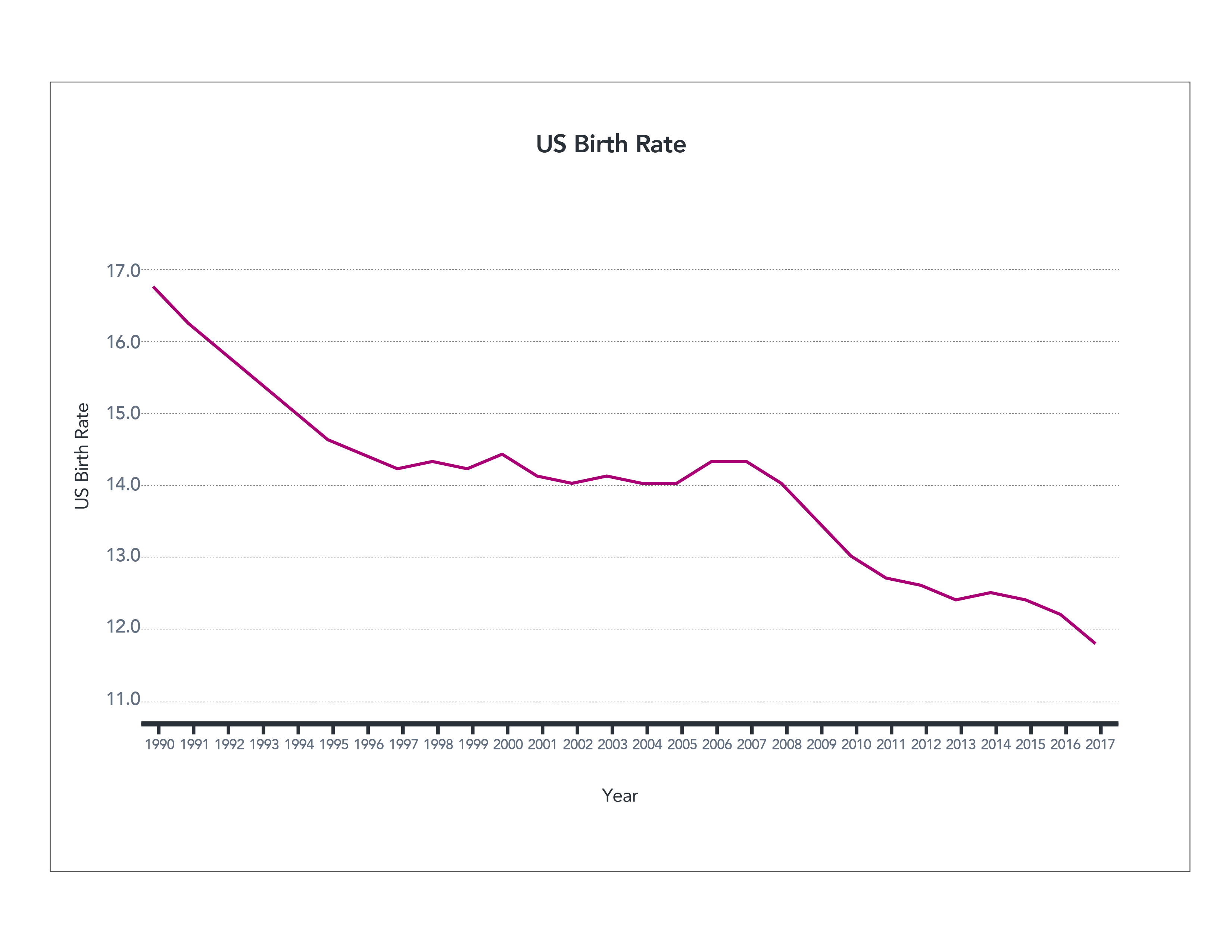

The information is correct, but what happens if we truncate the axis again?

The declining birth rates begin to look much more significant in the following chart. This visualization also highlights that the steady decline seen above wasn’t actually so steady. From 1997 to 2008, the birth rate stayed more or less the same. So which graph is accurate? Again, technically both.

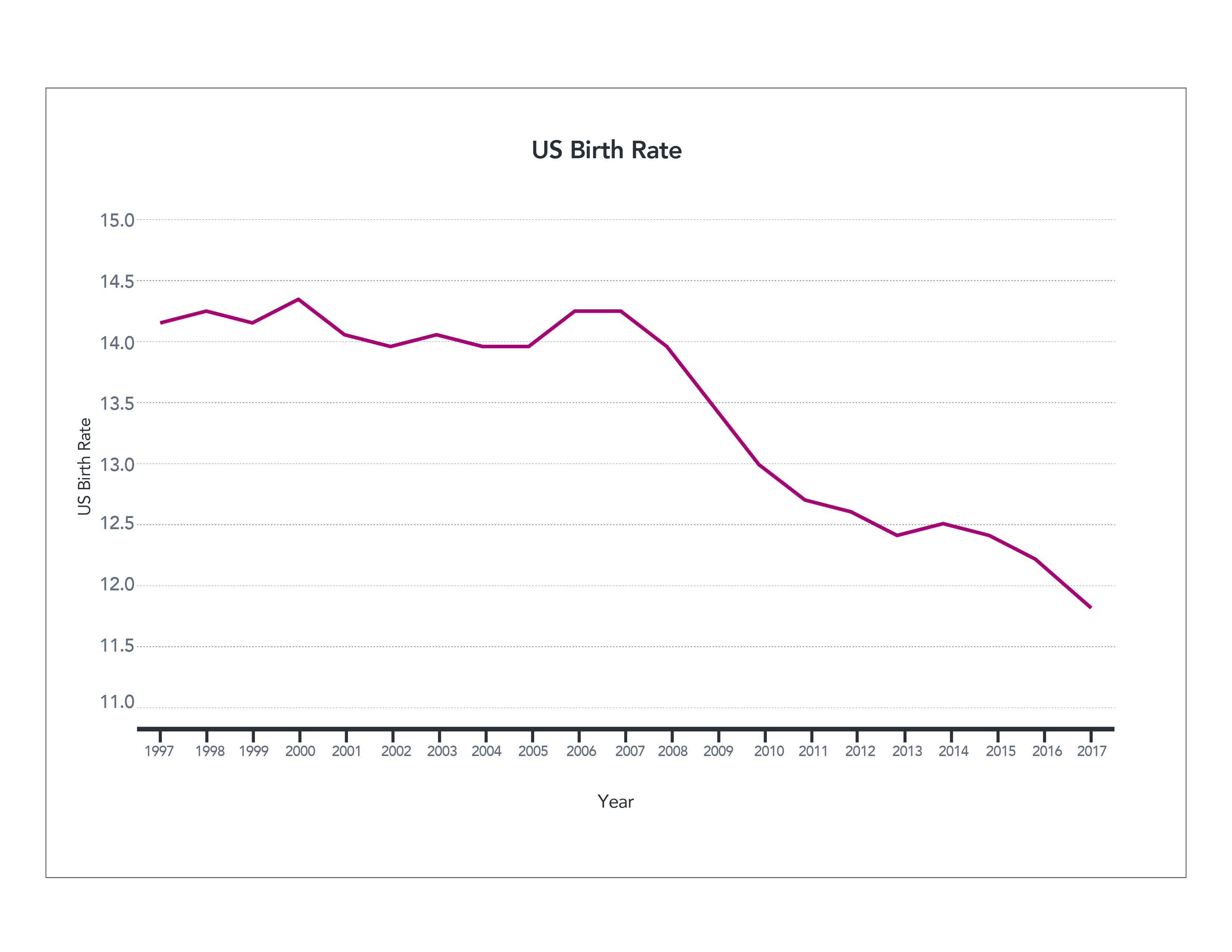

Both highlight different aspects of the story using the same data. If an author wanted to highlight the pattern of steadiness from 1997 to 2008, they might use the second graph. If they wanted to highlight the slow and steady decline, they might choose the first. An author may even further manipulate the information by focusing on a specific time frame.

Figure 4. US Birth Rate (truncated axis) World Bank

Now take a look at a graph depicting birth rates that starts in 1997, below. This data visualization makes it look like something happened in 2008 that caused a sudden, unprecedented downturn in birth rates. When we have access to the larger historical perspective, we can see that declining rates occur over the last 30 years, but the context is lost in this presentation. This could be a case of intentionally misleading the reader. The author may choose not to give the reader the full picture in order to reinforce a specific point.

Figure 5. US Birth Rate (1997-2017) World Bank

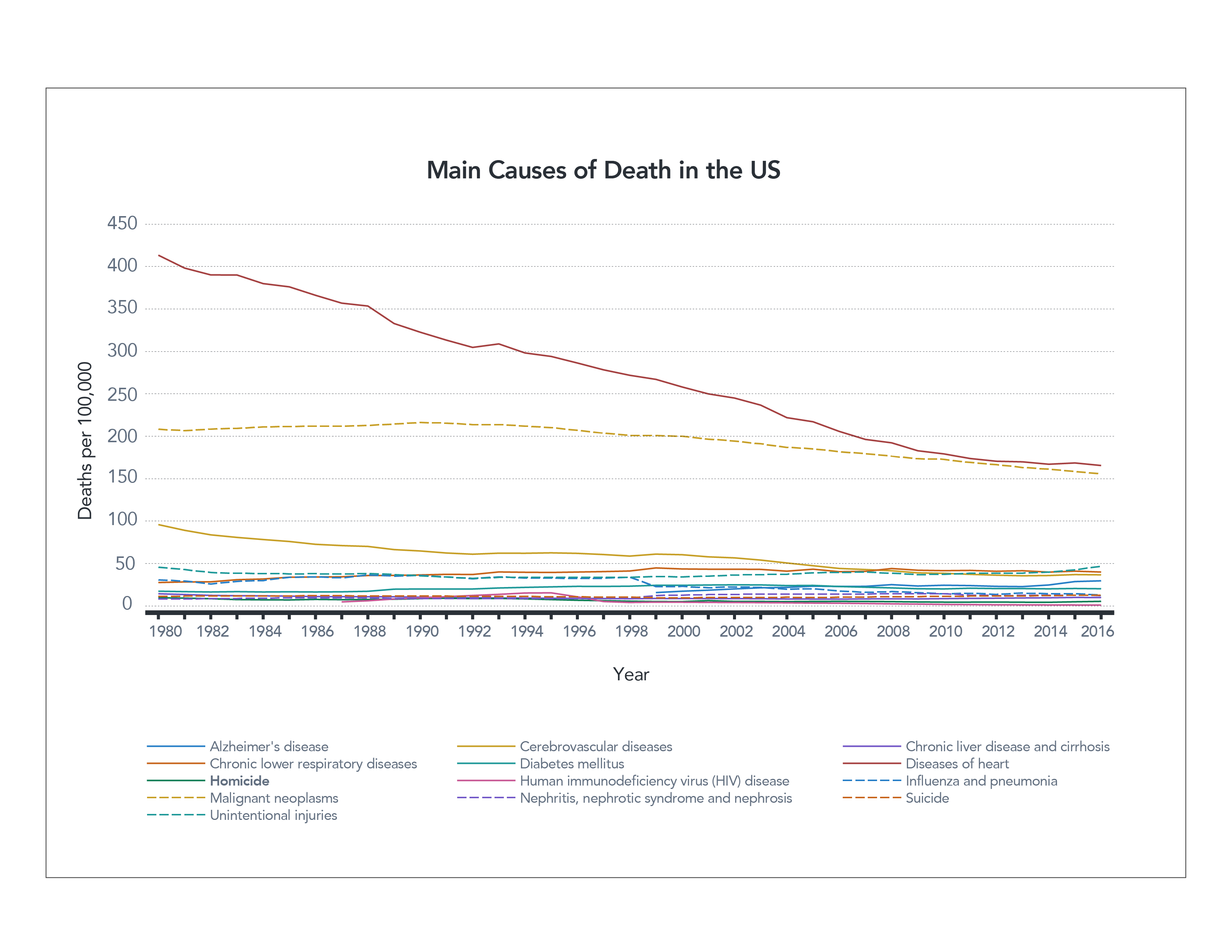

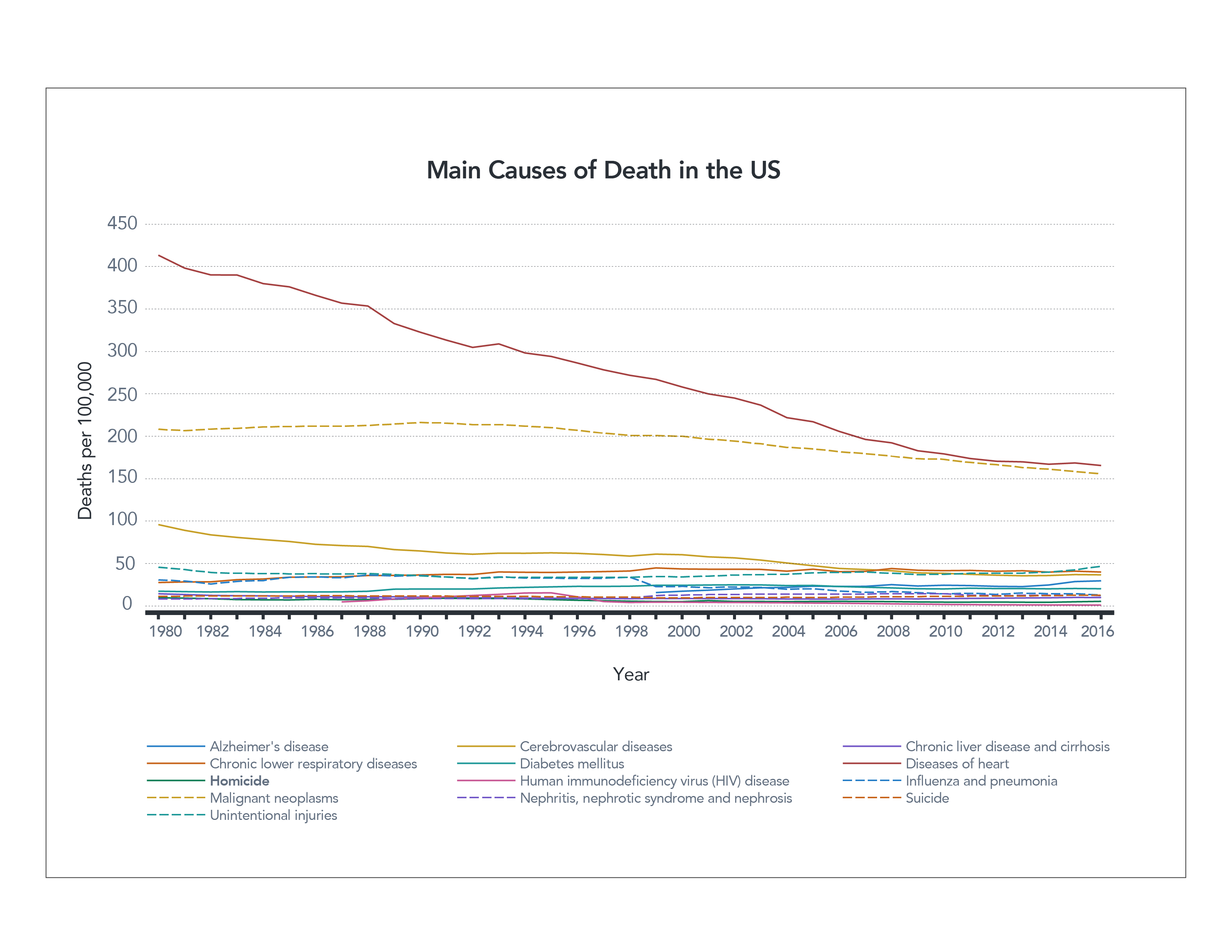

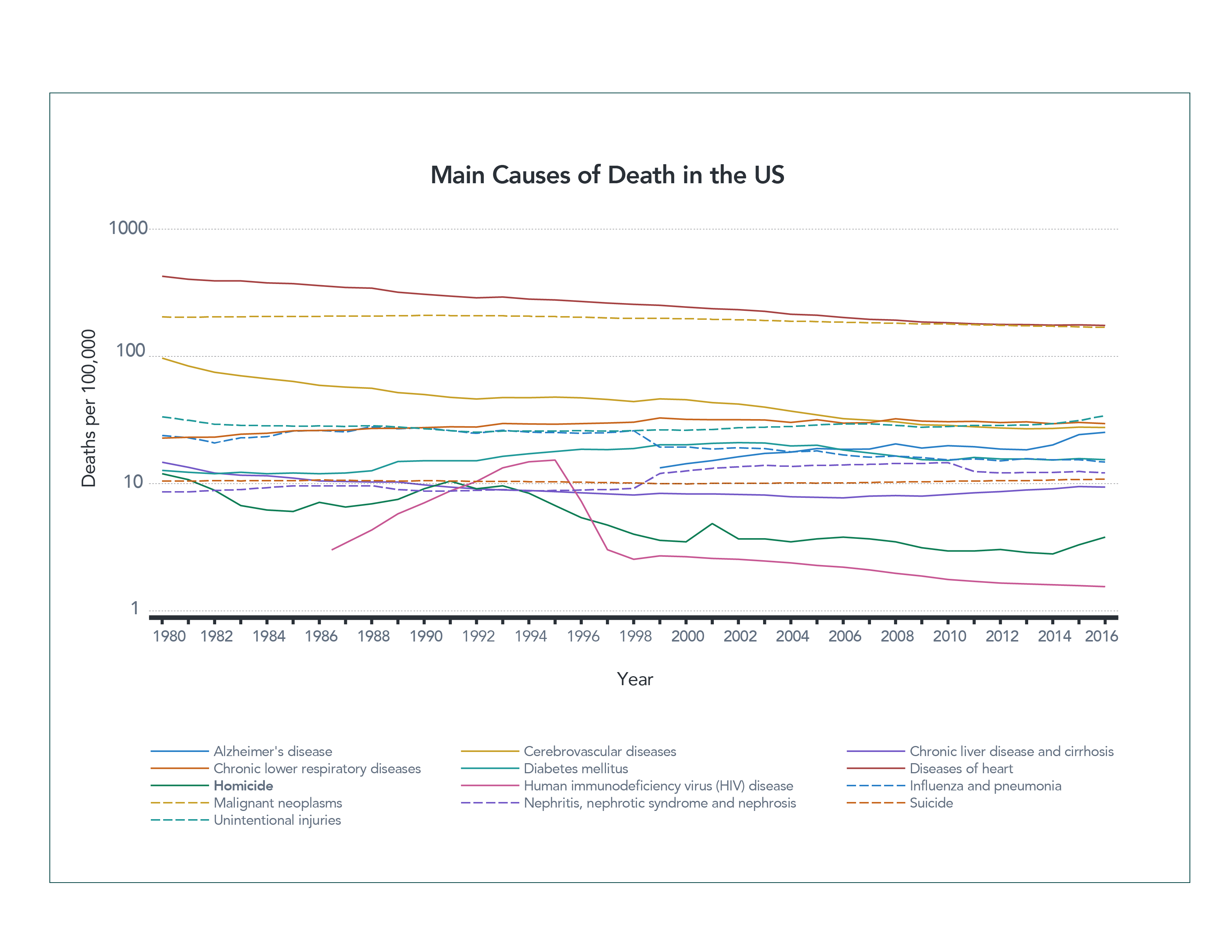

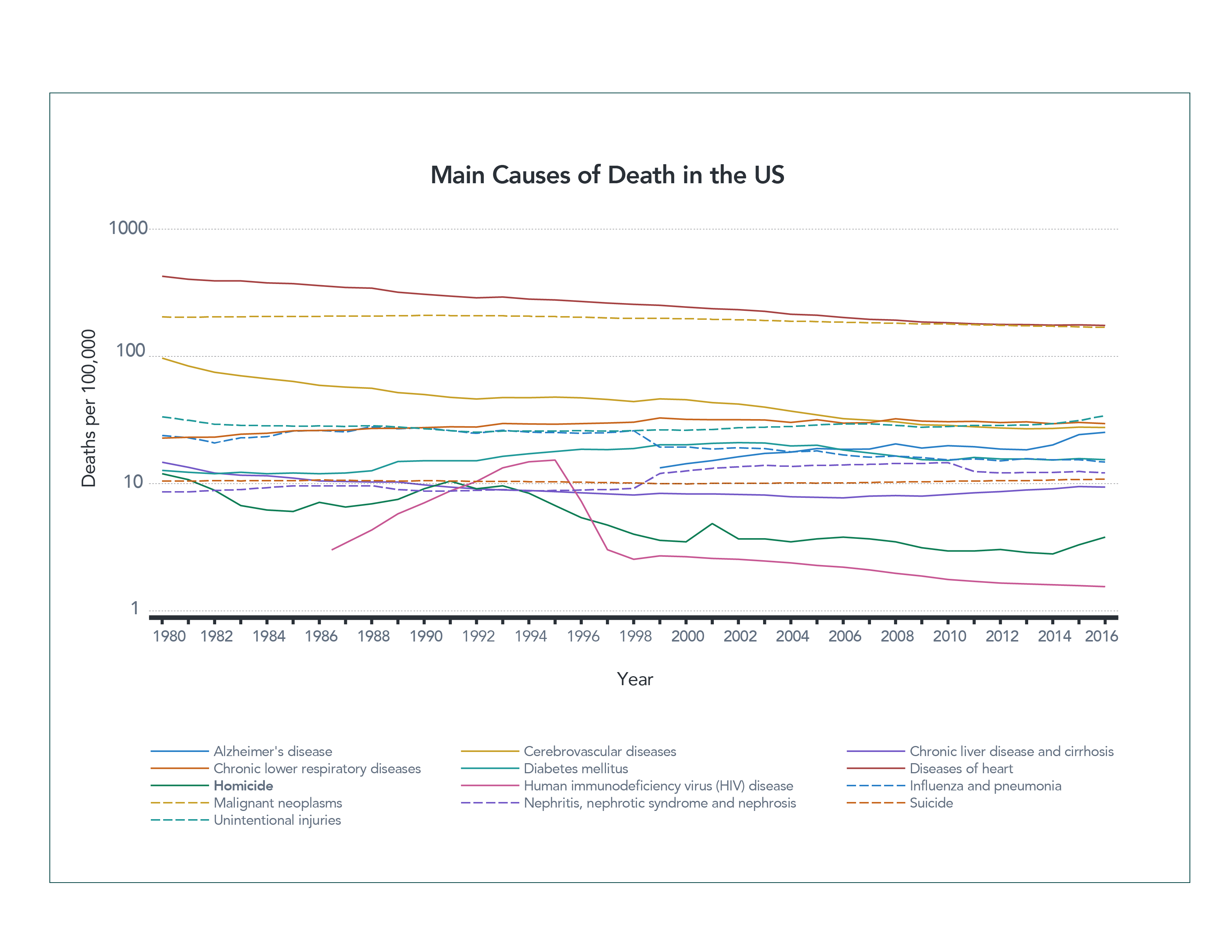

Here’s another example that may be particularly hard to interpret. Sometimes authors wish to present data that occurs on very different scales. The chart below shows the leading causes of death in the U.S. over time. Heart disease, the number one cause of death, killed around 400 people per 100,000 in 1980. The fourth most common cause of death, unintentional injuries, killed approximately 40 people per 100,000. What’s harder to see are the rates of the lowest–ranked causes of death. They’re all clustered at the bottom because of the scale of the vertical axis, making them hard to read.

Figure 6. Main Causes of Death in the US (linear axis) CDC

Understanding a logarithmic scale

One way to fix this is by using a logarithmic scale. This means that values from 1-10 are given the same vertical real estate as values 10-100, and 100-1,000. Using a logarithmic scale can help spread out data that have significant differences in values. You then can see individual trends in each line much better. By spreading out the data in the chart below, you can see the drop in deaths from HIV much more clearly than in the first graph.

However, logarithmic scales are not necessarily something most people are familiar with, and they can be challenging to read properly. You might look at this chart and note that there has been a slight decrease in the number of deaths caused by heart disease from 1980 until now, but in reality the number has been reduced by more than half, from about 400 to 160 people per 100,000.

Figure 7. Main Causes of Death in the US (logarithmic axis) CDC

Both graphs have their value. One allows you to see the lower values more clearly; the other is easier for most people to interpret. Which is the appropriate one to use? Unfortunately, the answer is “it depends.”

As with all other forms of information, authors will choose the one that most accurately communicates their purpose. That purpose might be to persuade you or simply present a particular piece of information more prominently. What matters most is how you, the reader, respond to the data.

You can be a better consumer of data visualizations by examining the charts and graphs you see more carefully. Take note of whether a vertical axis has been shortened or distorted in some way, for example. Consider what the data might look like if presented differently. Examine the data that’s been chosen, what’s been left out, and if the graph tells the whole story. Could you gather more information to give the graph better context?

Asking and answering these types of questions will make you a smarter and more responsible consumer of data. You’ll be able to find the true answers behind the data and distinguish those from the information the author was specifically trying to draw attention to.

Test yourself: Take our data quiz (here or below)!

Related articles:

- Six strategies for making sense of data in the media

- Exploring statistics in the media

- Understanding complications with data collection

- Evaluating claims made from data

- Special look at issues with infographics

- Spotlight on data in social media

- How to be savvy about data in the news

- Quiz: Can you make sense of data?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Making sense of data: Six strategies for making sense of data in the media

The series described below, presented by our partner SAS, explores the role of data in understanding our world. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

Data can be a powerful tool. It helps us to understand the world with more precision and greater clarity. Data is often the foundation for research, news articles and social media posts. Authors rely on data to help tell their story or prove their point. Because of its power to influence our understanding and decision–making, it’s essential that we learn how to confidently and critically consume the data we encounter.

If data is so intertwined with our daily lives, how then do we gain the skills to make sense of it, ask the right questions and draw the right conclusions?

We will address these questions and more in this blog series and cover a number of data analysis and presentation topics.

Diving into charts and graphs

When we talk about data visualizations, we’re referring to charts and graphs that help people visually make sense of large amounts of data rather than comparing raw numbers. Charts and graphs make it possible to see patterns and trends more clearly. At times, however, they can create confusion due to the way they’re presented. They can be misleading even if the underlying data is accurate. We’ll explore some of the common decisions that graph designers make when presenting information and how these decisions may impact what you see and understand.

Exploring statistics in the media

Whether it’s climate change or economic growth, statistics are often used to reinforce and better explain issues we face. Yet, there are many ways to use statistics to represent similar information. The type of measure or statistic used can significantly alter the story being told, so it’s important to be careful and understand the numbers. We’ll look at commonly used statistics and how they are often presented to help you understand what those numbers really mean.

Understanding complications with data collection

Even though data represents relevant issues, it is largely impossible to capture a completely accurate picture of the world around us. Instead, researchers rely on data collection methods to gather a close approximation. Unfortunately, the tools used can unintentionally skew the results. Therefore, it is important to understand the context of data creation. We’ll discuss key questions about the data collection process so you can determine what conclusions you can draw from the data.

Evaluating claims made from data

Data is often used to justify claims or statements about our world. However, it’s important to consider the context in which that data was collected to understand whether those claims are justifiable. We’ll look at two areas of concern – when authors use data to make comparisons and when research funding may introduce bias.

Special look at issues with infographics

Infographics are designed to be visually appealing tools that can communicate a lot of information. But their focus on visual design often makes them hard to interpret correctly. We’ll discuss some common issues with infographics and how they tie into the principles we discussed previously.

Spotlight on data in social media

Social media is a powerful tool for communication, and many people are creating their own content to share messages broadly. However, individual content creators may be more likely to post data and graphs that are misleading. One reason is that the flashiest stories are often shared the most rapidly and widely. We’ll discuss how social media encourages users to forgo the guidelines discussed in previous posts.

That’s a lot of information about data to cover, but it’s important. Data matters, and we’re excited to start the journey to understanding it better with you.

Test yourself: Take our data quiz (here or below)!

Related articles:

- Diving into charts and graphs in the news

- Exploring statistics in the media

- Understanding complications with data collection

- Evaluating claims made from data

- Special look at issues with infographics

- Spotlight on data in social media

- How to be savvy about data in the news

- Quiz: Can you make sense of data?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

March on Washington demonstrates democracy at work

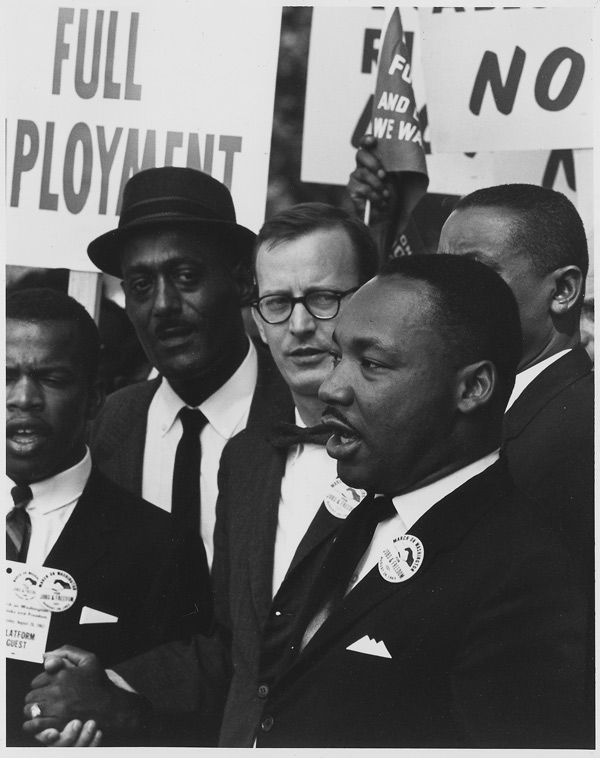

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks at the March on Washington. National Archives, Records of the U.S. Information Agency, Record Group 306 (National Archives Identifier 542014)

The rights of all Americans to freely assemble and to bring grievances to the government’s doorstep are intrinsic to American democracy and enshrined in the First Amendment. It’s what we’ve done for generations, perhaps most memorably on Aug. 28, 1963, when 250,000 people descended on Washington, D.C., to participate in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. That day, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial, and it became a lasting touchstone of the civil rights movement.

But earlier that summer this now-seminal event was far from a sure thing. President John F. Kennedy initially opposed the march over fears of unrest that could derail civil rights legislation. After he decided to support the march, the Los Angeles Times received a message that its headquarters would be bombed unless the paper called the president a racial slur in print.

And during the planning, death threats targeted King and other key figures. Activists around the nation also received bomb threats. Meanwhile, opponents in Congress sought legislation to block the march. Some argued the demonstration was an “illegal assembly” that would cause violence and should be banned.

Despite this atmosphere of intimidation, the march took place peacefully, galvanized a movement and proceeded into the history books.

2020 march on Washington

This Friday, on the 57th anniversary of the march, the American tradition of public protest will continue when thousands of people again travel to Washington to call for racial justice. The Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network organized the march in response to frustration over the killing of George Floyd in the custody of Minneapolis police in May, as well as other acts of violence against people of color. The Black Lives Matter movement also will march.

And just as in 1963, Friday’s demonstration faces challenges. Because of COVID-19 public health concerns, the event will include requirements for limited seating, social distancing, and other safety protocols. These concerns also prompted the NAACP to instead schedule a 2020 Virtual March on Washington, while the Movement for Black Lives will hold a virtual Black National Convention.

At NLP, we help young people understand the essential roles of the rights guaranteed by the First Amendment in a robust democracy. As Americans, we all must recognize the importance of these rights and ensure their protection for everyone.

Opposition to 19th Amendment relied on false narratives

This week marks the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which gave women the right to vote. It took the women’s suffrage movement decades to achieve that goal, thanks to entrenched discrimination that severely restricted women’s lives.

Opposition to women’s suffrage relied on false narratives that seem particularly outrageous, and sometimes comical, even for that era. For example, an Atlantic magazine article Why Men Thought Women Weren’t Made to Vote noted the common theory that the mental effort of voting could make women infertile. In addition, mainstream science also deemed women’s brains to be unfit. “And if women overexerted their already inferior brains, the thinking went, their health could suffer,” the article explains.

Brutality and discrimination

Yet, the supposedly fragile nature of women did not prevent authorities from treating suffragists with brutality. Consider the 1917 arrests and imprisonment of nearly three dozen women picketing outside the White House. Their jailers gave them maggot-infested food, beat the women and force-fed those who went on a hunger strike. The D.C. Court of Appeals ruled the arrests unlawful, and freed the women.

While the 19th Amendment extended the vote to all women, in reality, black women (and for a time, Native American women) could not broadly exercise that right. Discriminatory laws in the South kept many Blacks — women and men — from the polls until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. The voter suppression tactics targeted at people of color also were based on false narratives.

False narratives persist

However, while these events and the opposition to the right to vote might sound like relics of an ancient civilization, it’s important to remember that false narratives persist. Such tactics can boost efforts to deny people their rights as citizens and denigrate segments of our population. In modern elections, false narratives raise false alarms about voter fraud and sow distrust of widely accepted voting methods.

Remember, news literacy is essential to being well-informed about how government works and to recognizing false narratives. Use your news literacy skills and knowledge during this election season to avoid misinformation — and to help others do the same.

NLP’s e-learning platform is now free

NLP is now offering its signature e-learning platform Checkology® free to help ease the transition to remote teaching and hybrid learning environments for educators and families. By removing barriers to access, NLP will support educators across the country with essential news literacy lessons at a time of urgent need. Misinformation about COVID-19, the upcoming presidential election and nationwide demonstrations against racial injustice has sown confusion, divided voters and put people’s lives at risk.

Checkology teaches young people to recognize and debunk misinformation, understand the vital role of a free press in a democracy, and become informed and engaged participants in civic life. Leading journalists, along with First Amendment and digital media experts, guide students through the platform’s 13 interactive multimedia lessons. (One foundational lesson is translated into Spanish.) Featuring real-world examples from social media and news sites, these learning experiences resonate with students, test their understanding and teach them critical-thinking skills. Checkology has been updated for the 2020-21 school year, making it even easier to use, with one-click integration, drag-and-drop lesson customization and in-platform support.

NLP now on Flipgrid

In addition to free Checkology, NLP is partnering with Microsoft’s platform Flipgrid to help educators connect with more students through social learning. Teachers create “grids” around available topics, or develop their own topic material for the platform, with question prompts that students answer by video. NLP’s content includes various news literacy topics, many building on Checkology lessons, as well as activities for students, including fact-checking “missions” and misinformation “quests.”

To further support educators, and to build a community around news literacy education, NLP is also creating a national news literacy educator network. As part of this new educator network, NLP is training teachers, librarians and school administrators across the country to support a news literacy curriculum, help find opportunities for local partnerships and build channels of communication for their communities as local news literacy champions.

Educators interested in becoming ambassadors can access NLP’s online application at www.newslit.org, starting on Aug. 17. The network will formally launch in January 2021. You can send questions to [email protected].

NLP board welcomes journalist Enrique Acevedo and political consultant Whit Ayres

We are pleased to welcome two esteemed colleagues to NLP’s board of directors: Enrique Acevedo and Whit Ayres. Enrique and Whit bring diverse perspectives, significant professional expertise and a passion for our mission to NLP’s board. Their contributions will help us implement our strategic expansion and solidify our position as the nation’s leading provider of news literacy education.

Enrique Acevedo is a correspondent for the 60 Minutes spinoff program 60 in 6 on Quibi. Previously, he was an Emmy-award winning anchor of Univision’s Noticiero Univision Edición Nocturna, the network’s late-night news program. He has covered major news stories around the globe in English and Spanish for print, broadcast and online media, including three U.S. presidential elections, the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, the humanitarian crisis in Haiti and the drug wars in Latin America.

Whit Ayres is a leading Washington, D.C. political consultant with over 30 years of experience in polling and survey research for high-profile political campaigns and associations. He is the author of 2016 and Beyond: How Republicans Can Elect a President in the New America and founder and president of North Star Opinion Research, a national public opinion and public affairs research firm in Alexandria, Virginia.

The Voting Rights Act remains relevant 55 years after passage

The sixth of August marks 55 years since President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law. The legislation outlawed discriminatory voting practices adopted in many Southern states after the Civil War, including literacy tests and poll taxes.

The Act’s goal was to make it impossible to thwart the aims of the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which nearly a century earlier established the right to vote for Black men in America. In the decades after the amendment was passed, Black voters faced obstacles to voting in many states, including voter intimidation. It took the Voting Rights Act of 1965, with its enforcement powers, to remove many of the barriers preventing Black people from fully exercising their voting rights.

Because of a Supreme Court ruling seven years ago, however, the issues the Voting Rights Act raised and the voter suppression it sought to address remain relevant today.

In December the U.S. House of Representatives passed legislation to restore a key provision of the Act. The bill would return election oversight of some state and local jurisdictions to the federal government as a way to prevent voter suppression, a provision the Supreme Court struck down in 2013. And last week, the House approved a proposal to rename the legislation in honor of Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), the civil rights icon who died of cancer on July 17.

Voting rights in 2020

Efforts to suppress voting and disenfranchise marginalized communities continue. But today it often involves social media content that misleads voters. Tactics include spreading rumors that polling places have closed or moved, sharing falsehoods that an election has been canceled or wrongly telling voters they can vote by text or phone.

Such methods occur every election year, and you can expect to see them gain momentum as November’s presidential election nears. That’s why NLP will launch a voter education campaign this fall to help the public identify credible sources of information and become more news-literate.

That’s because news literacy skills enable voters to discern credible sources of information regarding early voting, voting by mail, and other voting issues. They also help protect every voter’s right to make his or her vote count in November. And news literacy can build the essential critical thinking skills citizens need to remain engaged and informed participants in our democracy.

Understanding COVID-19 data: Age isn’t everything

This piece is part of a series, presented by our partner SAS, that explores the role of data in understanding the COVID-19 pandemic. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field. (Check out other posts in the series on our Get Smart About COVID-19 Misinformation page.)

As the United States enters its seventh month in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen myths created and debunked, fears and hopes elevated and dashed, and initial assumptions become lessons learned.

The most important piece of conventional wisdom proven false is that the virus targeted only older people and that younger generations were largely safe from infection. However, data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on June 19 tells a different story. As of May 30, 70% of those who tested positive for COVID-19 were under 60. In March, by comparison, approximately 25% of positive cases occurred in people under 50.

One theory for the surge of cases in those under 60 is that in the early days COVID-19 testing was restricted to only the sickest patients. Therefore, many people with mild cases — often those under age 65 — may not have been diagnosed. Regardless, the new CDC report underscores that younger generations are vulnerable to COVID-19 infections and can get very sick or die.

Yet, the elderly and those with certain chronic health conditions do remain most vulnerable to severe illness and death. Experts have been exploring questions about vulnerability and how to protect at-risk populations since an outbreak of 129 cases of COVID-19 among patients, staff and visitors resulted in 40 deaths at a Kirkland, Washington, nursing home in February.

COVID-19 risk factors about more than age

Initially, public health officials focused primarily on age when evaluating COVID-19 vulnerability. But the definition of vulnerability quickly expanded to include those with underlying health conditions like diabetes, asthma, cardiovascular disease, and obesity. We now know that individuals over age 65 who contract COVID-19 are more likely to develop severe complications not solely due to age, but also because they may also have underlying health conditions. This partly explains why 40% of U.S. deaths from COVID-19 have occurred in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities.

Knowing that age and underlying health conditions help determine the risk of vulnerability is important, but it doesn’t fully explain why so many cases occur in those facilities.

Other factors that aid in the spread of infectious disease may be present:

- Shortages of personal protective equipment like masks and gowns can hinder necessary precautions.

- Shared bedrooms and common living spaces among residents make it nearly impossible to effectively socially distance.

- Transfers of residents from hospitals and other locations can introduce exposure to disease.

- Frequent visitors, employees and other providers coming from outside the facility further increase risk.

Data makes the difference

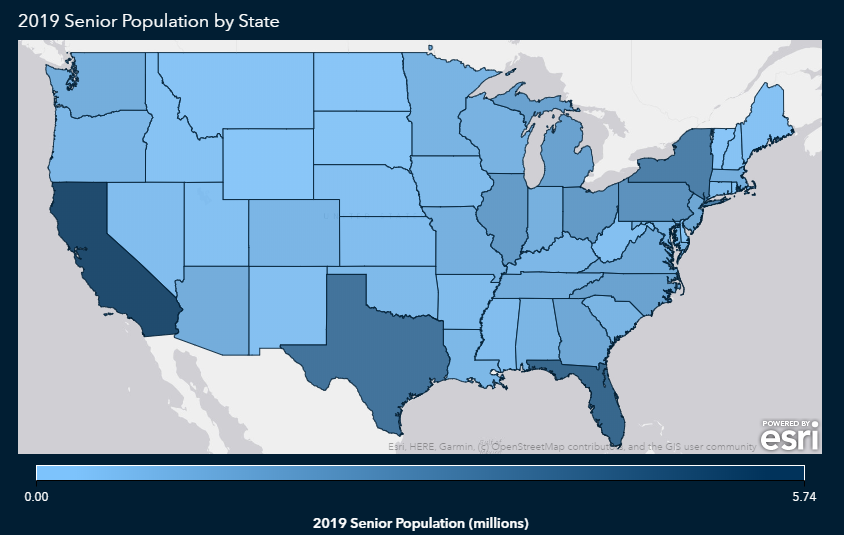

Analyzing data about aging populations helps us better understand why these individuals are at greater risk for COVID-19. For example, we can use data to see where the most vulnerable populations are located and how they are impacted by the virus. When we look at the geographic distribution of population by age along with data on secondary conditions that may be present, we get a better idea of the dangers facing aging populations. This deeper knowledge reveals how contributing factors can lead to high susceptibility to COVID-19 and helps us understand how to protect these populations

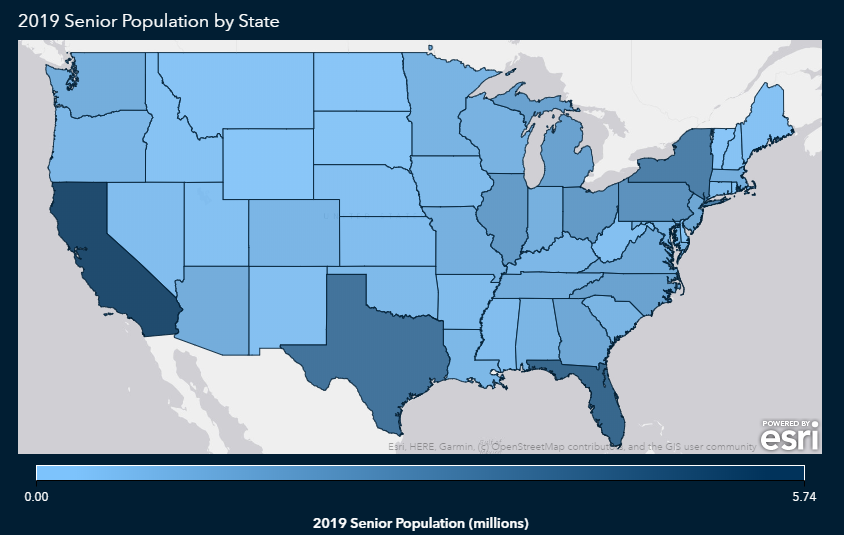

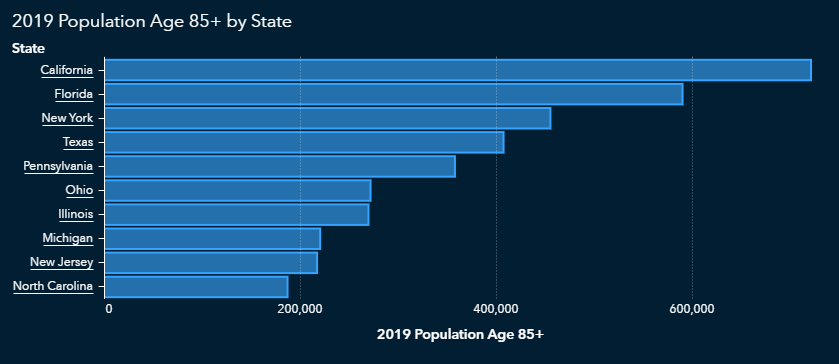

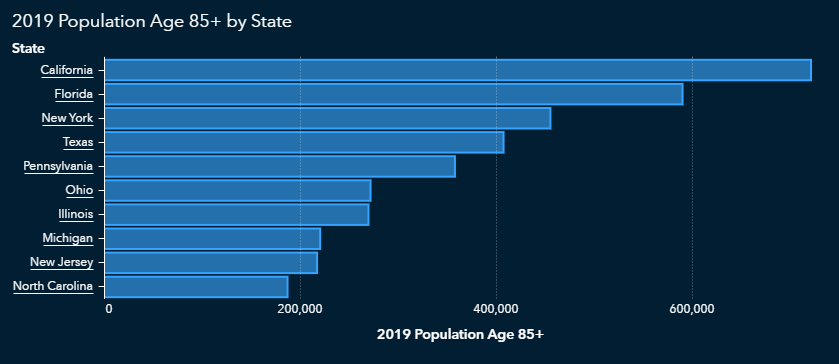

There are more than 50 million Americans over the age of 65. California, Florida, Texas and New York have the highest number of older Americans, with Sumter County, Florida, having the highest overall percentage in the nation.

As we might expect, those states also have higher concentrations of people over age 85, since that’s a subset of the 65-and-over population.

Do COVID-19 risk factors follow state lines?

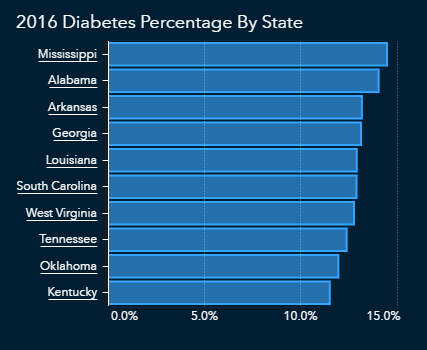

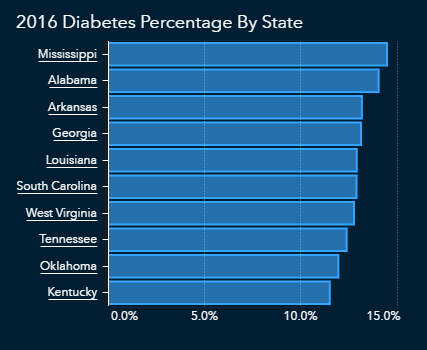

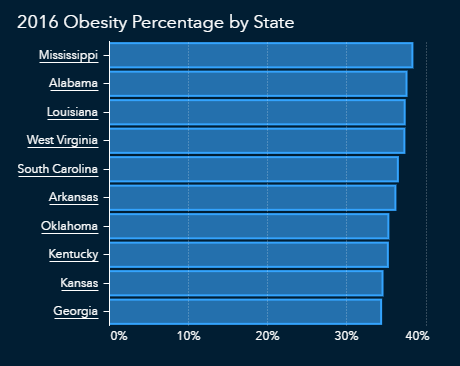

Obesity and diabetes often go together, and according to CDC data, the states most affected by obesity and diabetes overlap and tend to be concentrated in the southern United States.

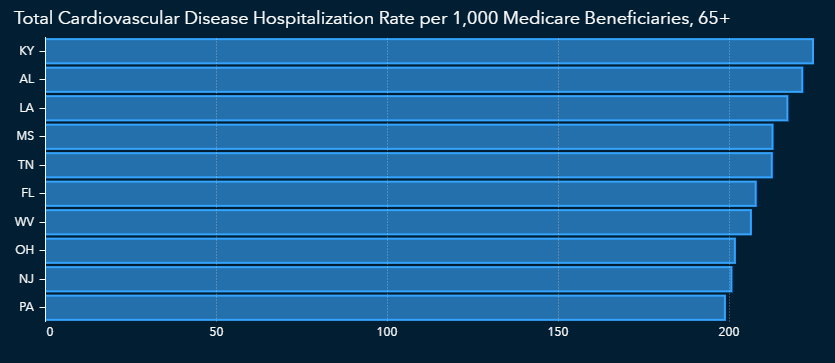

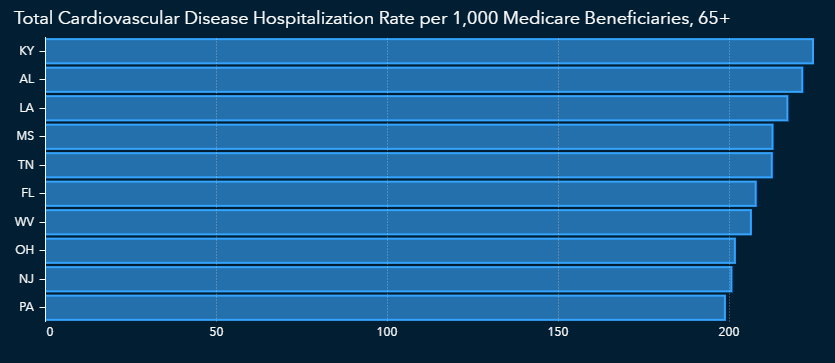

The CDC also reports cardiovascular disease in terms of hospitalizations, with a focus on those over age 65. The data shows an overlap with states that have higher numbers of diabetes and obesity. This could mean that those hospitalized with cardiovascular disease might also have diabetes and/or obesity, which would put them at even higher risk of severe complications from COVID-19.

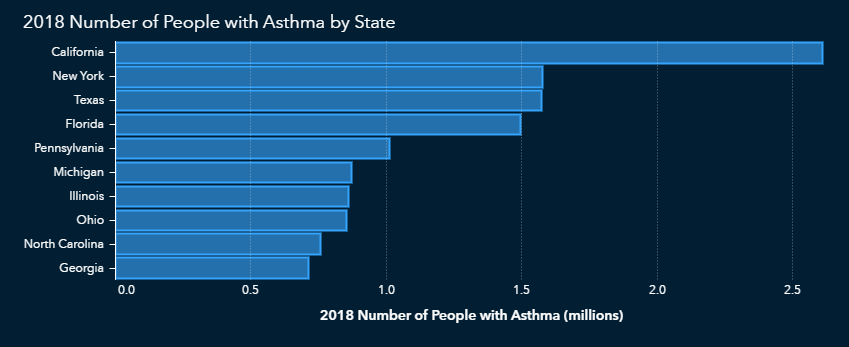

Finally, we must look at data regarding lung conditions such as asthma. Some states with a high incidence of asthma cases overlap with those states that have large populations with at least one of the other risk factors we’ve examined.

What does all this mean?

The data appears to show that there are vulnerable people everywhere in the U.S., but there are concentrations in several areas. As states loosen restrictions initially put in place when the pandemic hit the U.S., it becomes important to evaluate population data within each state to ensure that those who are most vulnerable are protected. In recent weeks we have seen upticks in cases in some states that loosened restrictions.

It is crucial that we identify risk factors and set up proper safeguards. By evaluating additional risk factors and analyzing data within our own communities, we gain a more complete understanding of the COVID-19 impact. When we consider the whole individual, rather than age alone, we better understand what it means to be vulnerable during this pandemic and going forward.

Other articles in this series:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Virginia high school teacher named NLP’s 2020 Educator of the Year