Alan Miller tackles confirmation bias in NCSS Journal

Reprinted with permission of the National Council for the Social Studies:

Confronting Confirmation Bias: Giving Truth a Fighting Chance in the Information Age

By Alan C. Miller

Guns. Immigration. Climate change. Abortion. Race relations. Trade. Global terrorism.

Across the spectrum of politically charged issues confronting the nation, Americans are more deeply divided along ideological lines than they have been in decades. This division extends beyond partisanship: The Pew Research Center reported earlier this year that ideological divides are widening along educational and generational lines as well.

Across the spectrum of politically charged issues confronting the nation, Americans are more deeply divided along ideological lines than they have been in decades. This division extends beyond partisanship: The Pew Research Center reported earlier this year that ideological divides are widening along educational and generational lines as well.

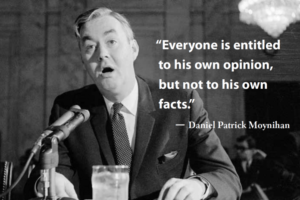

These days, it’s well worth recalling a comment by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a former Harvard University professor, White House aide and four-term senator: “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.” This is underscored on an almost daily basis by the 2016 presidential campaign, where civic discourse has been anything but civil, and truth seems to be under hourly assault.

In fact, Americans increasingly tend to see their news through prisms of red and blue — to seek confirmation of their existing beliefs, rather than information that might contradict or complicate them. We often gravitate to sources aligned with our own biases and partisan leanings, and we are served a steady diet of reinforcing information and images by algorithms that shape and filter what we discover through online searches and social media.

Confronting students with this reality is a crucial component of teaching news literacy, which we define as the ability — as a student, as a news consumer and as a citizen — to discern credible information from raw information, opinion, misinformation and propaganda. However straightforward that may sound, it’s actually astonishingly complex. Today’s information ecosystem presents students with unprecedented opportunities to access and parse an enormous and rapidly growing sea of information; to create and share and contribute to the national conversation; to be empowered and have their voices heard. But it also offers an incredible array of challenges to know what to believe — a proliferation of raw information, viral rumors and fake news sources; pervasive clickbait; videos of events staged to promote a cause or advertiser; repurposed images; and stealthy propaganda.

Giving students the ability to navigate this terrain involves teaching them skills that draw on core concepts borrowed from the practice of journalism itself. Students need to be able to understand newsworthiness, sourcing, documentation, fundamental fairness and the aspiration of minimizing bias in a dispassionate search for truth. They also need to be familiar with concepts of transparency and accountability. Not only do they need to be reminded that all information is not created equal, they also need to learn the conceptual language, the critical tools and the habits of mind to examine news and information and determine its credibility for themselves — and to do so as objectively as possible.

This is especially important since research shows that when faced with information that contradicts our beliefs, the thinking portion of our brain — our capacity to reason — tends to shut down, and our emotional defenses kick in. Facts, in theory, should prompt us to change (or at least reassess) our views; instead, they often cause us to grasp ever more tightly to our erroneous beliefs or misconceptions. Moreover, those with more education and higher levels of political knowledge are actually more prone to engage in this behavior than those with less education.

In a 1985 study, when researchers at Stanford University showed televised images from American media coverage of the 1982 war in Lebanon to two groups of viewers — one pro-Israel and the other pro-Arab — each side concluded that the reporting was slanted in favor of the other. In short, the researchers wrote, “Our results provide a compelling demonstration of the tendency for partisans to view media coverage of controversial events as unfairly biased and hostile to the position they advocate.” It is not difficult to imagine this study repeated with any number of divisive subjects today.

The first step in countering the natural tendency to confirm our biases is to recognize it — to teach students how our biases affect the way we seek, accept, share and act on information. This so-called confirmation bias prompts people to believe assertions they agree with more readily and less critically, even when these claims are provably false. Conversely, disconfirmation bias is the tendency to disregard assertions that challenge one’s beliefs, even when they are demonstrably true, or to simply dismiss them as the result of media bias.

“If you specifically train people to recognize these biases and they have a mental checklist of what to watch out for, they can overcome them,” said Daniel J. Levitin, the James McGill Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Neuroscience at McGill University and author of the recently published A Field Guide to Lies: Critical Thinking in the Information Age.

Such training is especially important, since this sort of bias can lead to a belief that any news reports that contradict one’s own views are automatically biased. This can, in turn, lead to the cynical view that all information, including news reports, is driven by ideological, commercial or personal bias.

Such a lack of distrust of the news media is reflected in a recent survey by the Gallup Organization (sponsored by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the Newseum Institute) that found that 59 percent of college students have little or no trust in the press to report the news accurately and fairly and that only half turn to a traditional news organization first to get an accurate picture of world events on issues they care about.

It is vital that we teach students how to understand and react to news coverage (or what purports to be news) with skepticism, rather than cynicism. While they may indeed encounter reporting that is inaccurate, unfair or biased, they need to be able to make such judgments on a case-by-case basis, rather than generalizing and dismissing the news media because they disagree with what they are seeing, reading or hearing.

Once students are made aware of confirmation bias, it is important to guide them through experiences that help to make them increasingly aware of their own biases. One tool is Harvard University’s Project Implicit, where anyone can take an online test to assess his or her own conscious and unconscious biases on 90 different topics, including politics, ethnicity and religion.

A valuable next step is to educate students about the hidden role of algorithms — which, by determining what users encounter online, can serve to reinforce these biases.

Personalization algorithms use our gender, age, location and online activity to guess the information — advertisements, news reports, social media posts, search results and almost anything else available online — that we want or are most likely to interact with. This, in turn, determines the information that is provided, prioritized and featured in our searches and social media feeds and on the websites we visit. For all the useful filtering these complex calculations do as they learn to serve us information that aligns with our current interests and needs, they also deliver information that reinforces — rather than challenges — our existing ideas and ideological leanings. Combined with the natural inclination to seek out news sources or publications with which we’re likely to concur, personalization can create what best-selling author and internet activist Eli Pariser has called a “filter bubble.”

Examples of this personalization are vividly captured in The Wall Street Journal’s “Blue Feed, Red Feed,” which demonstrates Facebook’s role in creating ideological “echo chambers.” This site allows users to see two contrasting feeds that emerge when they plug in a controversial subject — such as guns, abortion, Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton.

The Journal explains: “If a source appears in the red feed, a majority of the articles shared from the source were classified as ‘very conservatively aligned’ in a large 2015 Facebook study. For the blue feed, a majority of each source’s articles aligned ‘very liberal.'”

But filter-bubbling isn’t the only pitfall of algorithms. Because they are valuable and proprietary, algorithms are also extremely resistant to transparency. This makes it difficult to understand what they use (what consumer actions generate usable data), what they have (what pieces of data they gather about anyone) and how they work (what third-party data they are tapping to make assumptions about you). There is also evidence that algorithms can reflect the biases of their creators, who are disproportionately male and white.

Moreover, there are growing concerns about privacy, now that new tools that generate even more data are infiltrating every corner of our lives. They include social media platforms that try to learn about our dispositions, our friends and family, and even our senses of humor; mobile operating systems and apps that learn our daily routines, travel habits and favorite destinations; and web-based services that can see other websites we visit — sometimes even when we’re logged off.

While there are ways to opt out of personalization and data collection, it is becoming increasingly difficult to do so. These data-producing digital tools are now necessary in our daily lives, and algorithms do have a legitimate purpose: helping us to filter and navigate an information landscape that would otherwise be impossibly large and unwieldy.

Once students are made aware of their biases — and the ways that algorithms can reinforce them — they can be encouraged to overcome these cognitive barriers by consuming news from a wide range of sources, and by seeking out opinion pieces from a variety of points of view. On social media, they can “like” or follow credible sources of news — including those they may not be inclined to agree with — so that these will show up on their feeds, along with posts shared by friends. They can, in short, work to control and diversify their information diets.

Another teaching tool is to urge students to try to withhold judgment when they first learn of an event, especially on fast-breaking, chaotic and polarizing stories such as the recent shootings by or of police. The immediate aftermath of such events is invariably marked by waves of speculation, rumors, false reports and even conspiracy theories. It is imperative to follow the reporting over time until a verified, contextual and accurate account of events emerges.

Today’s ubiquitous, always-on, warp-speed torrent of news and information offers educators an abundance of teachable moments. This applies to a wide range of disciplines — including social studies, history, government, English, journalism and science — across nearly all grade levels. Teaching news literacy is also an engaging way to connect to the real world and contemporary issues.

But no single activity or tool can replace news-literate habits of mind. And when it comes to combating confirmation bias specifically, there is growing evidence that teaching students to follow these habits of mind can make a difference.

“Individuals who reported high levels of media literacy learning opportunities were considerably more likely to rate evidence-based posts as accurate than to rate posts containing misinformation as accurate – even when both posts aligned with their prior policy perspectives,” scholars Joseph E. Kahne and Benjamin Bowyer write in a soon-to-be published report, Educating for Democracy in a Partisan Age: Confronting the Challenges of Motivated Reasoning and Misinformation. “Those who reported no exposure to media literacy education, in contrast, were not more likely to rate posts with evidence-based arguments as more accurate than posts that contained misinformation.”

Two new resources are available to help educators develop their students’ ability to combat confirmation bias as well as other news literacy skills. The News Literacy Project’s checkology™ virtual classroom includes lessons that focus on bias, including confirmation bias, and the pervasive role of algorithms. The News Literacy Project also worked with Facing History and Ourselves to create Facing Ferguson: News Literacy in a Digital Age, a multimedia unit designed to help students become responsible consumers and producers of news and information.

Alan C. Miller, a Pulitzer Prize-winning former investigative reporter with the Los Angeles Times, is the founder and president of the News Literacy Project, a national education nonprofit, which recently launched the checkology™ virtual classroom.