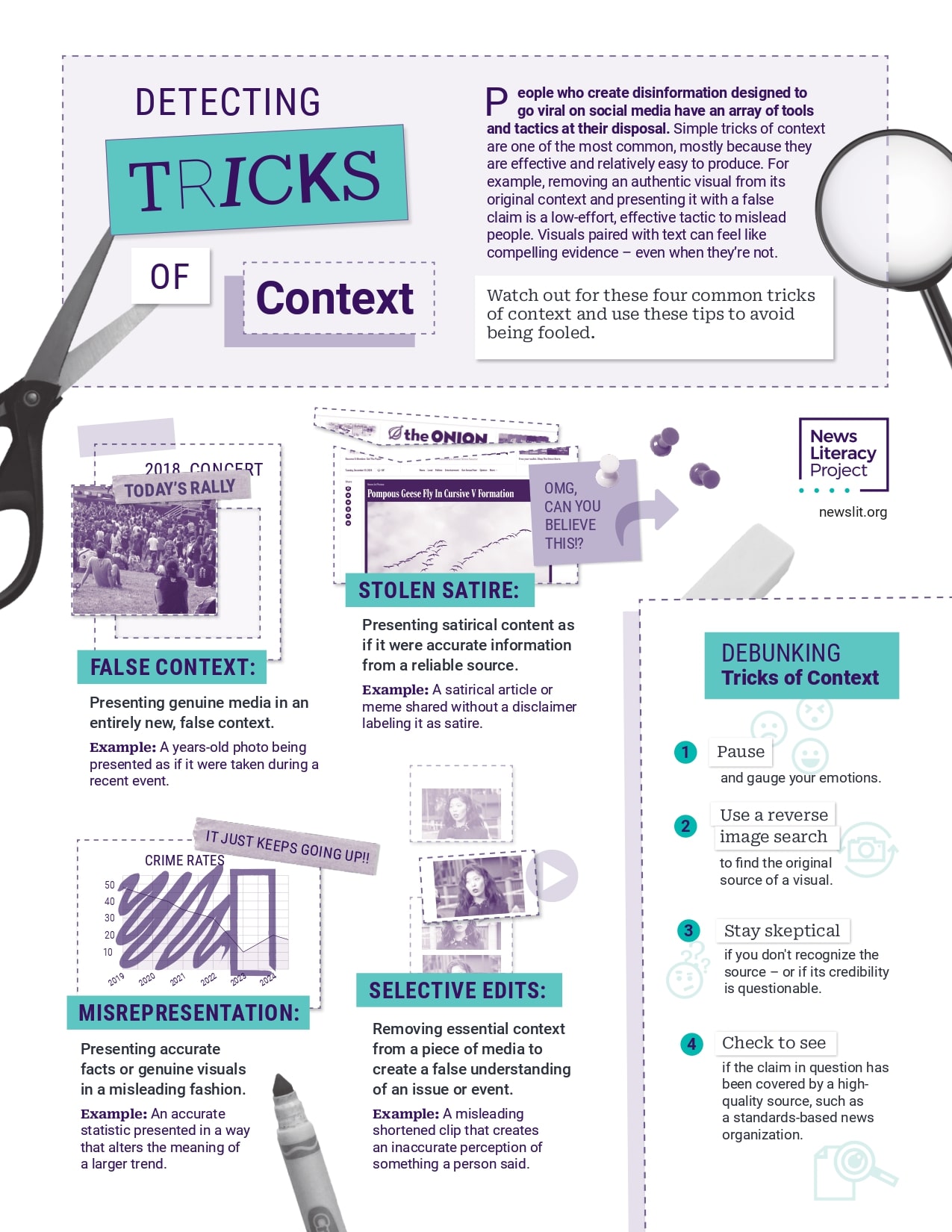

Detecting tricks of context

People who create disinformation designed to go viral on social media have an array of tools and tactics at their disposal. Simple tricks of context are one of the most common, mostly because they are effective and relatively easy to produce.

Watch out for these four common tricks of context:

- False context: Presenting genuine media in an entirely new, false context.

- Example: A years-old photo being presented as if it were taken during a recent event.

- Misrepresentation: Presenting accurate facts or genuine visuals in a misleading fashion.

- Example: An accurate statistic presented in a way that alters the meaning of a larger trend.

- Stolen satire: Presenting satirical content as if it were accurate information from a reliable source.

- Example: A satirical article or meme shared without a disclaimer labeling it as satire.

- Selective edits: Removing essential context from a piece of media to create a false understanding of an issue or event.

- Example: A misleading shortened clip that creates an inaccurate perception of something a person said.

This infographic also includes a list of tips to debunk tricks of context and avoid being fooled.

“News Matters” Unit Plan

The News Literacy Project and TIME for Kids teamed up to create “News Matters,” a three-week unit plan intended for grades 3–6. Students begin by viewing and discussing a TikTok video created by the News Literacy Project that introduces the knowledge and skills students will explore throughout the unit. Then students proceed with a pre-assessment and introductory activities before heading into the lessons.

The core main lessons are:

- Distinguishing Fact from Opinion

- Zoning Information

- Recognizing Quality Journalism

- What Makes Something Newsworthy

- Learning the Lingo (journalism vocabulary review)

Each lesson builds foundational news literacy skills and provides opportunities for students to apply those skills through rich discussion prompts, collaborative group activities and challenging independent work.

The unit includes formative and summative assessments, such as a media scavenger hunt for students to demonstrate their understanding of the unit’s knowledge and skills goals and a “Stoplight Exit Ticket” that requires students to reflect on their own news consumption habits.

Like our Framework for Teaching News Literacy, this unit plan follows the three-stage, “backward design” process of Understanding by Design (UbD)®, a widely used curriculum design framework developed by Wiggins and McTighe. UbD focuses on building the conceptual understandings (the “big ideas”) associated with becoming news-literate and preparing students to apply their learning in authentic ways. UbD connects best practices in planning, teaching and assessing based on research in cognitive psychology and validated by studies on student achievement. It ensures educational value by offering time to teach and time to learn through deepened understanding with clearly articulated desired results.

Fact-Checker

In this lesson, students review examples of misinformation, identify a rumor pattern and create a list of red flags to watch out for. Then students will create a social media post warning others to be on the lookout for this type of misinformation and directing them to credible sources about the subject. Finally, students will discuss the impact of misinformation on a democratic society.

Intended for grades 3 and up, this lesson plan includes everything educators need to lead the lesson: essential questions, electronic materials, vocabulary, procedural directions, ideas for differentiation, checks for understanding, examples, an evaluation rubric, and ideas for an extension opportunity. Depending on the classroom, it could take between 30-60 minutes, or be broken up over a few class periods. At the News Literacy Project, we recognize educators are professionals and best understand the needs of their classroom. As such, we expect educators to take and adapt our resources, including this lesson plan, as they see fit.

Below is a preview of some of the elements in the lesson plan:

NLP standard 4: Students demonstrate increased critical habits of mind, including effective verification skills and the ability to detect misinformation and faulty evidence.

Essential Questions

- What are some different types of misinformation?

- What does it look like to be a responsible and news-literate participant in a democracy?

- If I see misinformation, how should I respond?

- How can misinformation and false beliefs undermine an individual’s participation in a democracy and threaten the political process?

- Can misinformation that other people believe still affect those who aren’t fooled by it?

Vocabulary

- Misinformation: Information that is misleading, erroneous or false. While misinformation is sometimes created and shared intentionally, it is often created unintentionally or as humor (for example, satire) and later mistaken as a serious claim by others.

- Viral rumor: An unsubstantiated claim that spreads widely on social media and elsewhere online. Viral rumors often use deceptive techniques (such as out-of-context or doctored images) to stir up strong emotions and amplify false or misleading ideas.

News Goggles: Karena Phan, The Associated Press

Standards-based news organizations care about getting the facts right. When false claims spread online, journalists and fact-checkers often step in to investigate and share their findings to help set the record straight.

This week, we talk to Karena Phan, a reporter for the news verification team at The Associated Press. Phan discusses the steps she takes to find and debunk misinformation trending online. We examine Phan’s recent fact check on a viral video falsely claiming to show the world’s tallest tree and explore how simple tools — such as a Google search or a reverse image search — can go a long way in separating fact from falsehood. Ready to fact-check like a pro? Grab your news goggles!

Note: Look for this newsletter feature the first Monday of the month. You can explore previous News Goggles videos, annotations and activities in NLP’s Resource Library under “Classroom Activities.”

Resources:

- “Misinformation” (NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom).

- “MisinfoChallenge: Fact-checking 101” (Checkology virtual classroom).

- Infographic: “Eight tips to Google like a pro” (NLP’s Resource Library).

Dig Deeper: Use this viewing guide for the featured News Goggles video to help students take notes on how to think like a fact-checker and verify information online.

News Goggles annotations and activities provide news literacy takeaways on timely topics. These resources feature examples of actual news coverage, including full news reports, headlines, breaking news alerts or excerpts.

This video originally appeared in the March 6, 2023, issue of The Sift® newsletter for educators, which explores timely examples of misinformation, addresses journalism and press freedom topics and examines social media trends and issues. Read archives of the newsletter and subscribe here. Stock music in this video was provided by SoundKit from Pond5.

Have feedback about this resource? Or an idea for a future News Goggles? Please share it with us at [email protected].

PitchIt! Student essay contest

PitchIt! Student essay contests happening in Colorado, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania and Texas

Grades: 6-8, 9-12

About

Student voices are catalysts for positive change in schools and communities. You can empower them to be well-informed and civically engaged when you participate in the News Literacy Project’s PitchIt! contest.

This is an authentic way to get middle and high school students to learn about and express their thoughts about current events from a news literacy perspective. In addition to exploring an issue important to them, they can help combat misinformation or work to protect freedom of the press.

To have your students participate in PitchIt! and get the most out of it, use NLP’s free resources and curriculum guides. You choose the top essays from your class to submit for judging and prizes.

Click here for a printable, one-page guide to participating in PitchIt!

It is the ideal time to start using Checkology® and other free resources to prep your students. You can also email your questions to [email protected] for more information.

- Pennsylvania deadline, March 1, 2024: Click here for details.

- Colorado deadline, April 15, 2024: Click here for details.

- Florida deadline, May 24, 2024. Click here for details.

- New York deadline, April 19, 2024: Click here for details.

- Texas deadline, April 26, 2024: Click here for details.

Not in one of these regions? NLP encourages you to contact your local news literacy ambassador or our staff ([email protected]) and adapt our contest rules to create a contest for your learning community.

Curious to what participating teachers had to say?

“PitchIt! utilizes news literacy curriculum to broaden the understanding of how media influences all of us every day. Students then analyze and learn for themselves the power of using information with and without bias. I highly recommend facilitating part or all of the curriculum in classrooms across the board in Social Studies, English, Science, and more. It shows students that language, facts, and biases impact us comprehensively.”

— Renee A. Cantave, iWrite magnet educator, Arthur and Polly Mays Conservatory of the Arts, Miami, Florida

“PitchIt! was a great experience for my students. Not only did it raise awareness among them regarding the importance of good writing and of an important current issue in our community, the culminating event gave contest winners a chance to verbally express their positions, while receiving important feedback.”

— Rolando Alvarez, Coral Way K-8 Center, Miami, Florida

Tired of feeling like you’re working in a vacuum? Sign up for NewsLitNation and our private NewsLitNation Facebook Group to connect and share with other educators across the country passionate about news and media literacy. As a member of NewsLitNation® you’ll receive special perks and the NewsLitNation Insider, our monthly newsletter that keeps you up to date about all things news literacy!

Evaluate credibility using the RumorGuard 5 Factors

Don’t get caught off guard. Recognize misinformation and stop it in its tracks by using RumorGuard’s 5 Factors for evaluating credibility of news and other information. This classroom poster displays the 5 Factors alongside “Knows” and “Dos” for evaluating credibility.

Learn about RumorGuard | Go to RumorGuard | The 5 Factors on RumorGuard

The 5 Factors

- Authenticity. Is it authentic?

The digital age has made creating, sharing and accessing information easier than ever before, but it’s also made it easier to manipulate and fabricate everything from social media posts to photos, videos and screenshots. The ability to determine whether something you see online is genuine, or has been doctored or fabricated, is a fundamental fact-checking skill.

- Source. Has it been posted or confirmed by a credible source?

Not all sources of information are created equal, but it can be easy to glaze over the significant differences while scrolling through feeds online. Standards-based news organizations have guidelines to ensure accuracy, fairness, transparency and accountability. While these sources aren’t perfect, they’re far more credible and reliable than sources that have no such standards. Viral rumors that confirm one’s perspectives and beliefs or that repeatedly appear in social media feeds can feel true, but if no credible source of information has confirmed a given claim it’s best to stay skeptical.

- Evidence. Is there evidence that proves the claim?

Misinformation lacks sound evidence by its very nature — but it often tricks people into either overlooking that fact or into accepting faulty evidence. Many false claims are sheer assertions and lack any pretense of evidence, while others present digital fakes and out-of-context elements for support. Evaluating the strength of evidence for a claim is a key fact-checking skill.

- Context. Is the context accurate?

Tricks of context are one of the most common tactics used to spread misinformation online. Authentic content — such as quotes, photos, videos, data and even news reports — is generally easy to remove from its original context and place into a new, false context. For example, an aerial photo of a sports championship parade from 2016 can easily be copied and reposted alongside a claim that it depicts a political protest that took place yesterday. In this false context, the photo may easily be perceived as genuine by unsuspecting people online. Luckily, there are easy-to-use tools that can verify the original context of most digital content.

- Reasoning. Is it based on solid reasoning?

Misinformation is often designed to exploit our cognitive biases and vulnerability to logical fallacies. These blind spots in our rational thinking can make baseless conclusions feel plausible or even undeniable — particularly when they reinforce one’s beliefs, attitudes and values. Conspiracy theorists, pseudoscience wellness influencers and propagandists commonly rely on flawed reasoning to hold their assertions together. Learning to logic-check claims is an important element in verifying information.

Know and do

Know:

• Standards of quality journalism

• Types of misinformation

• How cognitive biases work

• What makes evidence credible

Do:

• Reverse image search

• Lateral reading

• Critical observation

• Search internet archives

• Practice healthy skepticism

Three types of election rumors to avoid

Elections are the lifeblood of democracy, but political campaigns are often rancorous, controversial and polarizing events. As if the misleading claims and attack ads weren’t challenging enough for the public, bad actors further muddy the waters by pushing disinformation into our social media feeds.

These harmful falsehoods are designed to cause confusion and to undermine people’s faith in American democracy. Election disinformation can be tricky, but the same false narratives and claims tend to get recycled, which can make it easier to spot.

This infographic outlines three common types of election disinformation that are likely to circulate on social media during election cycles in the United States. It also includes tools and tips for locating credible information in your state or district.

Being familiar with recurring election disinformation themes can help inoculate you against the allure of new incarnations and iterations that occur regularly. It can also help you more efficiently debunk them and warn your friends and family members not to get taken in.

The three types of election disinformation this infographic focuses on are:

- “Ballot mule” accusations: A substantial portion of election misinformation revolves around baseless claims of voter fraud. Accusations of people (“mules”) illegally gathering large numbers of fraudulent ballots and delivering them to ballot drop boxes have become particularly common, despite the fact that such allegations lack evidence. More often, people who are authorized to return multiple ballots — such as designated agents for nursing home residents — are incorrectly portrayed as engaging in schemes to swing elections. Be wary of photos and videos of people delivering ballots that are framed as “evidence” of this type of fraud, which is extremely rare.

- Mail-in ballot rumors: Voting by mail is increasingly popular, but people are vulnerable to believing baseless allegations of mishandling ballots, partly because the chain of custody is less direct than with in-person voting. But mail-in voting is no less secure than in-person voting and examples of fraud remain rare (usually involving someone attempting to return a mail-in ballot previously requested by a since-deceased relative or housemate). If you see a claim about fraudulent mail-in voting, be extremely cautious and take time to verify it at least one credible source.

- Poll worker rumors: The increase in livestreams of election workers doing their jobs has given lots of raw fodder to strong partisans looking for anything they can construe as fraud. Keep in mind that there is legitimate and necessary election work that ordinary people are unfamiliar with and don’t entirely understand. Watch out for video clips and images out of context claiming that poll workers are manipulating the vote.

Don’t forget to check out the resources linked throughout the infographic, including ballot trackers, studies of actual fraud (which, again, is extremely rare) and analyses of viral election misinformation.

“Storm Lake” discussion guide on the importance of local journalism

This guide serves as a companion for adult learners and community members viewing the PBS documentary Storm Lake, a film about the struggles of sustaining local journalism and shows what these newsrooms mean to communities and American democracy overall. The guide has three main components: pre-viewing, during viewing and post-viewing activities.

The pre-viewing activities use one or more essential questions to focus on viewers’ engagement with news and their opinions about its relationship to their community and to American democracy. The essential questions are:

- What is news?

- What role does news play in your family members’ lives? In your community?

- Is news important in a democracy? Why or why not?

The during viewing portion includes discussion questions that can be completed whole or in-part, individually, or in small groups. These questions include:

- Is profit a motivation for the [Cullen] family? Why or why not?

- Art Cullen: “A pretty good rule is that an Iowa town will be about as strong as its newspaper and its banks. And without strong local journalism to tell a community’s story, the fabric of the place becomes frayed.”

- a. In your own words, what point is being made in this quote?

- b. Do you agree? Why or why not?

- c. How does this quote fit into your definition of news and its role in the community?

The post-viewing activities return to the essential questions raised prior to viewing and seek to extend engagement with local journalism. These options include keeping a news log for a week and evaluating a source (log included in the guide), interviewing family or friends about their news habits, engaging directly with local news organizations on social media or writing a letter or email to an editor with a suggestion for a story.

News Goggles: Seana Davis, Reuters

News Goggles annotations and activities provide news literacy takeaways on timely topics. These resources feature examples of actual news coverage, including full news reports, headlines, breaking news alerts or excerpts.

This video originally appeared in the March 7, 2022, issue of The Sift® newsletter for educators, which explores timely examples of misinformation, addresses journalism and press freedom topics and examines social media trends and issues. Read archives of the newsletter and subscribe here. Stock music in this video was provided by SoundKit from Pond5.

Misinformation thrives during major news events and can spread rapidly on social media by tapping into people’s beliefs and values to provoke an emotional reaction. Pushing back against falsehoods in today’s information environment is no small task, but a few simple tools can go a long way in the fight for facts. This week, we talk to Seana Davis, a journalist with the Reuters Fact Check team, about her work monitoring, detecting and debunking false claims online.

Misinformation often stems from “a grain of truth,” Davis said. “So it’s all about trying to weed out what is true and what is not.”

Davis sheds light on some common ways that viral falsehoods spread — including through miscaptioned videos and digitally altered headlines — and demonstrates how to fact-check false claims like a pro, using digital verification techniques such as reverse image search and advanced searches on social media. Grab your news goggles!

Resources:

- “Misinformation” (NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom)

- Reverse image search tutorial (Checkology virtual classroom)

- Infographic: “Eight tips to Google like a pro” (NLP’s Resource Library)

- Expert mission: “Can you search like a pro?” (Checkology virtual classroom).

Dig deeper: Use this viewing guide for the featured News Goggles video to help students examine how to recognize and debunk some common types of misinformation online.

Have feedback about this resource? Or an idea for a future News Goggles? Please share it with us at [email protected].

Fact-check it!

In this classroom activity, students join an “expert” group to learn one specific digital verification skill, then reorganize and join a “jigsaw” group to share what they learned with their classmates and to fact-check and analyze one example (or more) of viral rumors.

“Jigsaw” groups will work as a team to answer a series of questions about the authenticity and origins of visual examples (photos and videos) and the accuracy of any claims made (in an accompanying social media post or meme, for instance). Then, students extend their skills to explore each example further.

Each group will learn about five digital verification skills and consider how these skills can help them be more digitally savvy online as they work together to investigative a viral rumor. These verification skills include:

- Critical observation

- Reverse image search

- Geolocation

- “Lateral reading”

Students can review these skills by watching video tutorials available in the Check Center through the News Literacy Project’s free Checkology® virtual classroom.

This news literacy activity is suggested for grades 7-9 and 10-12+. It also makes the following essential questions available for exploration:

- What different types of misinformation exist?

- Why do people believe misinformation?

- What skills and tools do people need to effectively debunk misinformation?

The activity can help students apply what they have learned in the “Misinformation” lesson on Checkology. In this foundational lesson, misinformation expert Claire Wardle of First Draft — a disinformation research organization — examines five common types of misinformation. Students gain a new vocabulary to distinguish between different kinds of false content online.

About classroom activities:

NLP’s activity plans are designed to be “evergreen” news literacy resources that help educators introduce and reinforce specific news literacy skills and concepts. They are often best used as follow-up and extension activities from specific NLP lessons, either in the resource library or on Checkology.

Critical observation challenge: Was Elsa really arrested?

This upper elementary slideshow activity introduces students to critical observation skills, or the ability to identify key elements in a piece of visual information text. By closely examining an actual social media post by a police department in Illinois about the “arrest” of Elsa from Disney’s Frozen, students identify evidence indicating that the photos and claims in the post are misleading. Students also consider and discuss the primary purpose of the post and what led to people’s confusion.

Essential questions

- How can social media posts be misunderstood?

- Why are critical observation skills important when using social media?

- What problems can arise when people take a joke on social media seriously?

- How can a joke fail on social media?

This news literacy classroom activity is suggested for grades 4-6.

Key terms

- Critical observation

- Evidence

- Purpose

How to speak up without starting a showdown

Misinformation is always problematic, but when it appears alongside pet photos and family updates on social media, it can be especially frustrating and unwelcome. It’s one thing if a stranger spreads falsehoods online. But what should we do when we see misinformation shared by family and friends?

Misinformation is always problematic, but when it appears alongside pet photos and family updates on social media, it can be especially frustrating and unwelcome. It’s one thing if a stranger spreads falsehoods online. But what should we do when we see misinformation shared by family and friends?

Stepping into the role of fact-checker when it comes to loved ones can be tricky and stir strong emotions, so it’s worth preparing for — especially as more falsehoods seep across social media and into family and friend group chats.

While every scenario is different, following some general best practices can help keep the conversation civil and make the interaction worthwhile. Use these six tips — with some helpful phrases for getting started — as a guide on how to speak up without starting a showdown. It may not be easy, but talking to loved ones about false or misleading content can help them think twice about what to share in the future.

News Goggles: Can you trust it? Dolly Parton in People magazine

News Goggles annotations and activities offer news literacy takeaways on timely topics. These resources feature examples of actual news coverage, including full news reports, headlines, breaking news alerts or excerpts.

This News Goggles resource originally appeared in a previous issue of The Sift newsletter for educators, which explores timely examples of misinformation, addresses journalism and press freedom topics and examines social media trends and issues. Read archives of the newsletter and subscribe here.

After news broke on Nov. 16, 2020, that early data showed a vaccine from the drugmaker Moderna was nearly 95 percent effective, fans of American singer-songwriter Dolly Parton praised her $1 million donation to help fund COVID-19 vaccine research. Major news organizations including The Washington Post, The New York Times, CNN and BBC News covered the story.

But let’s imagine you came across this news online by seeing an article from People magazine. Can you trust it? Is People a credible source for news about this story? How do you know? In this edition of News Goggles, we’re going to examine sourcing and the use of hyperlinks in news reports as we consider what makes information credible. Grab your news goggles!

★ Featured News Goggles resources: These classroom-ready slides offer annotations, discussion questions and a teaching idea related to this topic.

Discuss: What makes a news source credible? When are hyperlinks important or useful to include? How can you fact-check information in a report that has been “picked up” from another news organization? Are magazines like People more or less reliable than news organizations like The New York Times? Considering the audience and purpose of each, which source do you trust more and why?

Idea: Ask students to read an online article from a standards-based news organization on a topic of their choosing, paying special attention to any hyperlinks in the text. Direct them to take notes on which details and phrases incorporate links, where each hyperlink leads and how its inclusion impacts the news report. (Does it add context? Lead to sources? Jump to previous coverage? Offer evidence or support?)

Resource: “Practicing Quality Journalism” (NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom).

Have feedback about this resource? Or an idea for a future News Goggles? Please share it with us at [email protected]. You can also use this guide for a full list of News Goggles from the 2020-21 school year for easy reference.

Sanitize before you share

Misinformation swirling around the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the importance of consuming and sharing online content with care.

Misinformation swirling around the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the importance of consuming and sharing online content with care.

Public health officials are urging us to practice good hygiene to help stop the spread of this virus — by washing our hands thoroughly and frequently, staying home as much as possible, and keeping a safe distance from others when we do go out.

We can also practice good information hygiene.

Just adopt the four quick and easy steps below to help stop the spread of COVID-19 misinformation. If we sanitize the process around our information habits, we can prevent misleading and false content — some of which is hazardous to our health — from being widely shared and potentially doing harm.

How to know what to trust

Misinformation comes at us every day, across many platforms and through a variety of methods. It’s all part of an increasingly complex and fraught information landscape. But what exactly do we mean when we say misinformation?

Misinformation comes at us every day, across many platforms and through a variety of methods. It’s all part of an increasingly complex and fraught information landscape. But what exactly do we mean when we say misinformation?

We define it as information that is misleading, erroneous or false. While misinformation is sometimes created and shared intentionally, it is often created unintentionally or as humor — satire, for example — that others later mistake as a serious claim.

Misinformation can include content that is wholly fabricated, taken out of context or manipulated in some way. Purveyors of misinformation often seek to exploit our beliefs and values, stoke our fears and generate anger and outrage. For example, during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, foreign governments, as well as organizations and individuals abroad and within the United States, flooded social media with disinformation. This nefarious form of misinformation is designed to sow discord, often around political issues and campaigns.

Don’t throw up your hands

While we might feel overwhelmed by the volume, frequency and increasing sophistication of misinformation in all its forms — from deepfakes and doctored images to outright propaganda — we can push back and regain a sense of control. News literacy skills that are easy to adopt can help us become smart news consumers.

To begin, we have identified seven simple steps that help you know what to trust. These steps can apply to information you encounter in the moment and over time. As these behaviors become ingrained in your information consumption habits, you will deepen your expertise.

You will then become savvy enough to flag misinformation when you see it, warn others about misleading content and help protect them from being exploited. In this way, you become part of the solution to the misinformation problem.

So start right here, right now by exploring the seven simple steps to learn “how to know what to trust.”