Adams discusses new survey, spread of misinformation on Facebook

Peter Adams, senior vice president of education, discussed a recent survey examining COVID-19 misinformation on Facebook in an August 4 interview with Chicago’s PBS affiliate, WTTW.

Adams was asked to weigh in on what social media companies can do to curb the spread of misinformation on their platforms, and why misinformation spreads so quickly across platforms like Facebook.

When asked how big a role social media plays in allowing COVID-19 vaccine misinformation to spread to the general public, Adams responded, “You know, the cause and effect is a little tricky here. It might well be that people who are cynical and nihilistic toward mainstream media turn to Facebook. It might be that folks who are not that way to start with seeing messages on Facebook that enflame them and turn them to misinformation. It’s probably both, but what we know for sure is that despite Facebook’s statements saying that they will take down misinformation if they see it, there’s a lot of COVID mis- and disinformation on the platform.”

View the full segment here.

Upon Reflection: The media’s dismissal of the Wuhan lab theory

For more than a year, the theory that the COVID-19 global pandemic began with the leak of a previously unknown coronavirus from a laboratory at China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology in late 2019 was roundly, even vociferously, dismissed by many scientists and most in the news media.

A New York Times report called it “a conspiracy theory.” Facebook deemed it “false” and took down posts making that claim. The fact-checking site PolitiFact dismissed it as “inaccurate and ridiculous. We rate it Pants on Fire!” (a term reserved for its most discredited assertions).

These conclusions were published despite the fact that the virus’s origin had not been definitively identified. The Wuhan Institute of Virology, located in the city where COVID-19 first surfaced, engages in cutting-edge studies of coronaviruses — but from the start of the pandemic, the Chinese government shared little information and blocked independent inquiries into the source of the outbreak.

Instead, based on disease outbreaks caused by other coronaviruses, the gospel among public health officials and the news media was that the deadly pathogen likely jumped from animals to humans in a market where live animals are sold.

That is, until recently.

In the past two months, the “lab-leak” theory has gone from “debunked” (The Washington Post) to “plausible” (The Wall Street Journal). In a May 5 article in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, veteran science writer Nicholas Wade made the case that it deserved serious consideration. Nine days later, the journal Science published a letter, signed by 18 leading scientists, calling for an independent investigation. On May 23, The Wall Street Journal reported that according to U.S. intelligence, three workers at the Wuhan lab sought hospital care in November 2019 “with symptoms consistent with both Covid-19 and common seasonal illness.” And in a statement on May 26, President Joe Biden announced that after an initial analysis, the U.S. intelligence community had “coalesced around two likely scenarios” for the virus’s origin — a species jump and a lab leak. He also ordered a second intelligence analysis, to be completed within 90 days, “that could bring us closer to a definitive conclusion.”

As a result, some news outlets have revised or corrected some of their prior reporting. Facebook reversed its ban. PolitiFact removed its fact-check from its database, but archived it “for transparency” and added an editor’s note.

The newfound credibility of the lab-leak theory has also sparked widespread criticism of media coverage, particularly from conservatives, and soul-searching among journalists themselves about a story that has enormous stakes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has already caused more than 176 million infections and 3.8 million deaths worldwide, along with catastrophic economic damage and dislocation. Confirmation that the virus (formally known as SARS-CoV-2) had escaped from the lab would be devastating for China’s standing in the world. It would also raise grave doubts about the types of research — and the safety procedures — at the Wuhan lab and at similar facilities around the world.

Should the lab leak be confirmed, the initial coverage of the pandemic would represent a massive journalistic failure. In any case, the mainstream news media was misguided in dismissing a theory that was always plausible.

This rush to judgment is a teachable moment, both for the producers of journalism and for those who read, watch and listen to their work.

The first lesson is that journalists in general, and science journalists in particular, were too credulous and reliant on outspoken scientists and failed to probe their potential conflicts of interest. For example, on Feb. 19, 2020, The Lancet, an influential medical journal, published a statement, signed by 27 public health scientists, that “strongly condemn[ed] conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin.” That statement “effectively ended the debate over COVID-19’s origins before it began,” according to a Vanity Fair investigationpublished on June 3 of this year.

But several months after the statement was published, a public records request revealed that the scientist who organized, drafted and signed it was involved in providing funding — including repackaged U.S. government grants — to the Wuhan Institute of Virology. “Conflicts of interest, stemming in part from large government grants supporting controversial virology research, hampered the U.S. investigation into COVID-19’s origin at every step,” Eban wrote.

Just four months ago, during a press conference in Wuhan, the leader of a World Health Organization team that was allowed into China for a four-week investigation called the lab-leak theory “extremely unlikely.” But China is an influential member of that organization, and the WHO team was given only limited access to independent data and Chinese facilities.

The second lesson concerns the predilection of journalists to dismiss the lab theory because President Donald Trump, who perpetuated so many falsehoods during his four years in office, was promoting it. His comments, along with his racially offensive references to the “China virus” and “kung flu,” were widely seen as attempts to deflect attention from his administration’s mishandling of the pandemic in the United States.

(One of the earliest proponents of the lab-leak theory, Sen. Tom Cotton, an Arkansas Republican and Trump ally, was also derided when he suggested during a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing in January 2020 that the virus may have originated in a Wuhan “superlaboratory.”)

“The ‘boy who cried wolf’ metaphor is at the heart of this,” Kelly McBride, the chair of the Craig Newmark Center for Ethics and Leadership at the Poynter Institute, told me. She said numerous journalists had told her that they had disregarded the leak theory because it was being espoused by Trump, so they viewed it as yet another example of disinformation.

The third lesson is to tread carefully when telling readers, viewers and listeners what to think by labeling something as false or fabricated.

Despite the lack of conclusive evidence for either the species-jump theory or the lab-leak theory, journalists didn’t simply express skepticism about the latter possibility; they dismissed it entirely, saying it had been “debunked” or calling it a ”fringe theory.” Particularly during the last two years of Trump’s presidency, the media became bolder in calling out his disinformation — but in this case, the circumstances didn’t support this extreme step.

“You can be too inconclusive when the conclusive evidence is there, a la climate change,” McBride told me. “And you can be overly conclusive when the evidence isn’t there, a la Wuhan.”

A small number of scientists and journalists did give the lab-leak theory credence early in the pandemic — but they were like trees falling in the forest that no one was around to hear.

As a result, journalists fell into a common narrative — some critics call it “groupthink” — that failed to give dissenting voices their due. In this respect, and because of the overreliance on self-serving sources, the media’s response to assertions that the virus had escaped from the Wuhan lab is reminiscent of the widespread failure of journalists to challenge the claims of the George W. Bush administration that Saddam Hussein was harboring weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

“Good journalism, like good science, should follow evidence, not narratives,” opinion columnist Bret Stephens wrote in The New York Times last month. “It should pay as much heed to intelligent gadflies as it does to eminent authorities. And it should never treat honest disagreement as moral heresy.”

And what are the lessons for all of us who read, watch and listen to the news?

- Seek out a wide range of sources, including those who challenge the conventional wisdom.

- Maintain a healthy skepticism. Even the most credible sources can be wrong. While, in most cases, a broad consensus of credible media and other sources (including scientists) can be trusted, this may not apply when evidence is unavailable or hidden.

- Don’t rush to judgment, especially where science is involved and evidence is inconclusive. Check your own biases; don’t automatically disregard everything that someone you typically disagree with says.

- Finally, follow the story as it evolves. Truth can take time to emerge. In this case, the story is far from over.

Read more from this series:

- Jun. 3: Recalling a great newspaper editor and what he represented

- May 20: Supporting journalists serving local communities of color

- May 6: The First Amendment and the need for vigilance

- Apr. 22: Spotlight — a special resonance

- Apr. 8: The 19th* — a nonprofit news startup made for the moment

- Mar. 25: How I became a ‘pinhead’ — a news literacy lesson

- Mar. 11: Fighting the good fight to ensure that facts cannot be ignored

- Feb. 26: Students’ enduring rights to freedoms of speech and the press

- Feb. 11: We need news literacy education to bolster democracy

Vaccines and Misinformation | How to interpret data on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines

This article is part of a series presented by our partner SAS that explores the role of data in understanding COVID-19. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

If there’s one thing people want to know most about a vaccine, it’s this: Does it work?

So naturally, as COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials were being completed and vaccines were being considered for emergency use authorization, the numbers that featured most heavily in the news were efficacy rates.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine boasted an efficacy rating of 95%, Moderna 94% and Johnson & Johnson 72%. But what do those numbers really mean? How can individuals use these numbers to make decisions for their families?

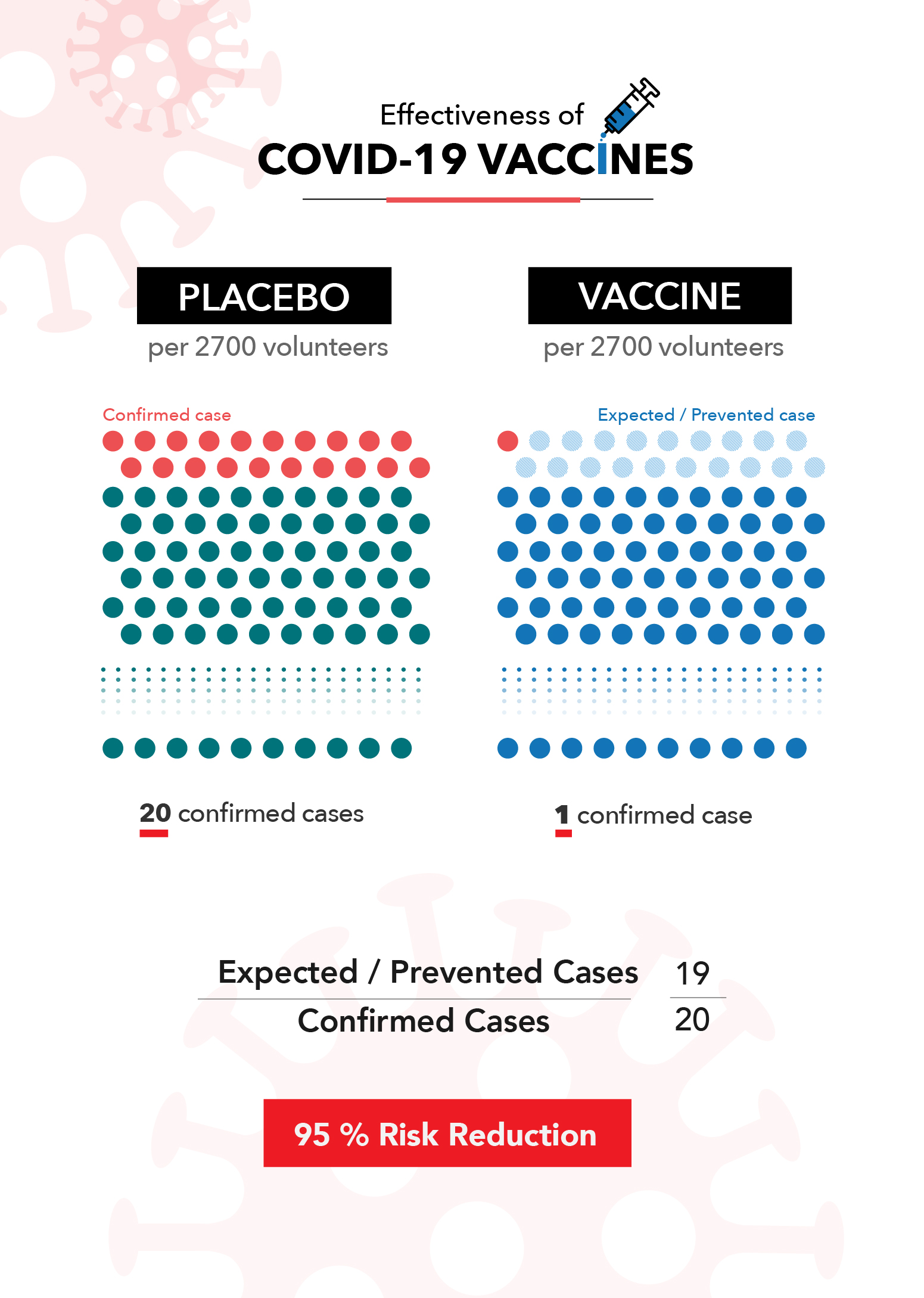

One common misconception is that a 95% efficacy rate means that 5% of the participants in the trial contracted COVID-19, and that similarly, 5% of the vaccinated population will catch it as well. That is not the case. The purpose of the efficacy rating is to show how much the RISK of catching the disease is reduced.

One common misconception is that a 95% efficacy rate means that 5% of the participants in the trial contracted COVID-19, and that similarly, 5% of the vaccinated population will catch it as well. That is not the case. The purpose of the efficacy rating is to show how much the RISK of catching the disease is reduced.

Let’s look at what this means using the Pfizer-BioNTech clinical trial. According to their released data, 160 out of the 21,728 people in the placebo group tested positive for COVID-19. Conversely, more than a week after receiving the second vaccine dose, only eight out of 21,720 people tested positive.

This means that over the course of the trial, it could be expected that the average unvaccinated person had a 0.7% chance of catching COVID-19. Alternatively, if you had received the Pfizer vaccine, you had a 0.04% chance of catching it. This is where their 95% efficacy rating comes from. It means that there were 95% fewer cases than would have been expected if the trial participants were not vaccinated.

Clinical trials can be hard to compare to one another because they occur during different time periods, in different places and have different definitions and criteria. This is a major reason health officials caution against comparing the efficacy numbers of different vaccines against one another. Small variances in the details of the trial can impact the final numbers.

The unique nature of clinical trials can also lead people to wonder how the vaccines perform in the real world, especially when issues like new variants come into play. Thankfully, we’re already seeing evidence that the real-world effectiveness of these vaccines matches up with the numbers reported in their clinical trials.

Now that a significant portion of the population is fully vaccinated, we can also examine recent, in-the-wild data to further understand how the vaccines reduce risk. We know that the vaccines aren’t perfect, and the CDC is actively collecting data on breakthrough cases (confirmed infections among vaccinated people).

As of April 26, the CDC reported 9,245 infections among the more than 95 million Americans who had been fully vaccinated. Using historical data* as a benchmark, an average of 264 vaccinated Americans tested positive for COVID-19 per day over the last two weeks of April. During that same period, the U.S. saw an average of 62,800 new cases per day among the entire population. That roughly equates to three cases per 1 million vaccinated Americans per day, compared to about 260 cases per 1 million unvaccinated Americans per day. It’s not perfect, but it represents a significant reduction in risk.

During that same two-week period, the U.S. recorded 8,926 total deaths due to COVID-19, 58 of which were fully vaccinated individuals. Given what we know about the size of the vaccinated and unvaccinated population, this means that vaccines likely saved at least 3,000 lives in those two weeks alone. The total lives saved is likely even higher, when one accounts for the fact that the demographics of the first groups of vaccinated Americans were among the most vulnerable for severe complications and death due to COVID-19.So what does all of this mean as you consider whether the vaccine is a good choice for you and your family? Getting the vaccine does not offer a guarantee that you won’t catch the disease or get seriously ill from it. But it does offer a very significant reduction of risk.

For example, consider that wearing seatbelts in a car is estimated to carry a 45% reduction in risk of death, and doing so is a choice most of us would make whether it was the law or not. Even if we believe our risk of an auto accident is low, we still make a conscious choice to further reduce the possibility of severe injury. Seatbelts don’t offer 100% protection, and neither do COVID-19 vaccines, but the data shows the added safety is worth it.

* As of May 14 the CDC has changed how they report breakthrough cases. Visit the CDC website for up-to-date information.

About SAS: Through innovative analytics software and services, SAS helps customers around the world transform data into intelligence.

About SAS: Through innovative analytics software and services, SAS helps customers around the world transform data into intelligence.

Vaccines and Misinformation | Understanding how misinformation can fuel vaccine hesitancy

Misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine is contributing to a hesitancy to get vaccinated. In an effort to separate fact from fiction and provide a better understanding of the reasons for that reluctance, we’re going to spend this week focusing on the issue and providing trustworthy information about it.

NLP’s staff members snapped selfies while getting their vaccine shot.

We’re starting with an update to our COVID-19 webpage, which includes links to credible health care organizations and reporting that have debunked many of the myths surrounding the vaccines. Additional resources dive more directly into the reasons people have expressed for not getting a shot. Our friends at SAS are providing context to the data about the vaccines that we hope will show you how effective they’ve been in preventing the spread and harm from the virus.

We’re also producing a special episode of our podcast Is that a fact? We’ll get insight from Dr. Erica Pan, California state epidemiologist and deputy director for the Center for Infectious Diseases at the California Department of Public Health, and Brandy Zadrozny, a senior reporter for NBC News who covers misinformation, extremism and the internet. They share their expertise on how the vaccines were created, their effectiveness, the impact of misinformation on vaccine hesitancy and how anti-vaxxers have used the pandemic to sow more confusion and grow their ranks.

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced new guidelines stating that “fully vaccinated people no longer need to wear a mask or physically distance in any setting,” along with some specific exceptions. It’s clear that the vaccinations are saving lives, reducing the health risks of the virus and helping us return to some semblance of normalcy. We hope that by providing this information, you can help the people in your community make informed decisions about getting the vaccines. Please share these resources, and remember, the best advice we can offer people who are hesitant to get a vaccine is to suggest that they talk to their health care provider about the benefits and risks of getting vaccinated.

Adams discusses covid rumors in New York Times piece

NLP’s Senior Vice President of Education Peter Adams discusses misinformation and conspiracy theories in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic with The New York Times in the Feb. 12 piece Get Wise to Covid Rumors.

During this pandemic, spreaders of misinformation have targeted people by using everything from printed newsletters to viral videos. But you’re most likely, said Mr. Adams, to encounter false information when it’s shared by people you know and care about — even if they’re doing it accidentally. Spreaders of false information are relying on that fact,” the article notes.

The reporter advises readers to keep in mind that misinformation is shared for the benefit of the person creating it, not the consumer. “Some individuals who share or create false information ‘are just looking for prominence online,’ said Mr. Adams. ‘They’re looking for attention, likes and shares.’ Others have been seduced by larger conspiracy theories with long histories, like the anti-vaccine movement, and may genuinely believe they are trying to help,” the article concludes.

Upon Reflection: Media needs to get COVID-19 vaccine story right

This column is a periodic series of personal reflections on journalism, news literacy, education and related topics by NLP’s founder and CEO, Alan C. Miller.

When it comes to reporting on the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines, context is everything.

As millions of doses are injected into the arms of people around the world, adverse events are inevitable, even under the best of circumstances.

A small percentage of the population will have allergic reactions. Because the two vaccines now in use in the United States (from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna) are highly, but not completely, effective, some recipients may become infected with the virus. And some people who have been vaccinated will get sick — or even die — from unrelated, if coincidental, causes.

The media needs to be discerning about the vaccination-related events it reports, and how it does so. Above all, it must avoid sensationalizing such incidents, whether in news reports or on social media.

Read the full commentary on Poynter.org.

Read more in this series:

- Dec. 17: Journalism’s real ‘fake news’ problem also reflects its accountability

- Dec. 3: Combating America’s alternative realities before it’s too late

- Nov. 12: “Kind of a miracle,” kind of a mess, and the case for election reform

- Oct. 29: High stakes for calling the election

- Oct. 15: In praise of investigative reporting

- Oct. 1: How to spot and avoid spreading fake news

Understanding COVID-19 data: Examining data behind racial disparities

This piece is part of a series, presented by our partner SAS, that explores the role of data in understanding the COVID-19 pandemic. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field. (Check out other posts in the series on our Get Smart About COVID-19 Misinformation page.)

by Mary Osborne

Are communities of color at greater risk for COVID-19? The question of COVID-19 racial disparities has circulated across media outlets since the start of the pandemic. Science tells us that viruses do not target individuals by race or ethnicity, and yet, this novel virus significantly impacts communities of color in disproportionate ways.

To understand why communities of color are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, we must look beyond race alone and consider other risk factors that may draw dividing lines. By examining why certain populations are more severely impacted than others, we can begin to identify the underlying causes. To do that, we have to look at the data. Although the data is limited within many communities of color, there is enough to better understand the impact of COVID-19 in certain communities.

Data has demonstrated how a person’s age or underlying medical conditions can be the difference between surviving COVID-19 or succumbing to it. But are there other risk factors to be considered and could any of those factors be tied to racial inequalities?

Population, race and COVID-19

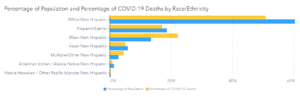

It’s no secret that minority populations have been greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, often at rates that are disproportionate to those of white people. The Black Non-Hispanic population has been hit particularly hard. While they represent 13% of the population in the United States, Black Non-Hispanics comprise over 22% of COVID-19-related deaths.

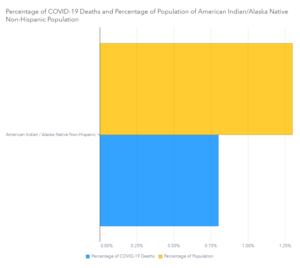

The disparities in cases and deaths by race vary from state to state, driven by percentages of population. However, a negative trend has emerged in one of the nation’s smallest populations — the American Indian/Alaska Native Non-Hispanic (AI/AN) group. AI/AN people make up around 1.5% of the U.S. population but have experienced almost 1% of total COVID-19 deaths. Let’s read that again: 1% of total COVID-19 deaths are attributed to the AI/AN population, which is enormous considering that this community is such a small percentage of the total population.

Source: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have reported that the AI/AN population has a case rate that is 2.8 times higher than the White population, a death rate that is 1.4 times higher than the White population, and a hospitalization rate that is 5.3 times higher than the White population. The hospitalization rate is higher for this population than any other population in the U.S.

Source: US Centers for Disease Control

Secondary risk factors and healthcare access

Yet, the COVID-19 numbers we see in the AI/AN population aren’t dissimilar to those seen in other communities of color. This is likely because they may share risk factors with other minority populations. Similar to members of the Black and Hispanic populations, many Native American families live in close quarters — sharing their homes with more than one generation or extended family. That is partially unique to the AI/AN population because housing on reservation lands is limited, and an increase in the Native American population in the last decade has put a strain on housing resources. These types of living arrangements pose a higher risk of spreading diseases like COVID-19.

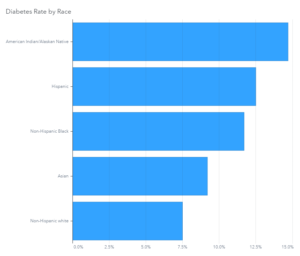

Within the AI/AN population, diabetes, obesity and hypertension have emerged as factors that increase risk of severe COVID-19 disease and the need for hospitalization. According to the American Diabetes Association, this disease is more prevalent in the AI/AN population than in any other racial or ethnic group. And AI/AN people are 50 percent more likely to suffer from obesity than Non-Hispanic white people. Hypertension is also common in this population, especially among people with diabetes.

Source: American Diabetes Association

Economic impacts

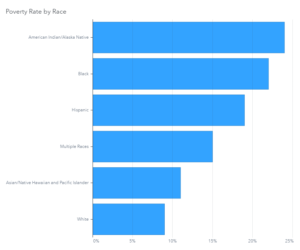

The long-term economic impacts from the virus also are disconcerting. AI/AN people have the highest poverty rates of any other U.S. racial ethnic group. Sociologist Beth Redbird from the Institute for Policy Research has found unemployment to be the most significant factor driving poverty in Native American populations. Given the current uncertainty with job markets and employment, an improvement in poverty rates is unlikely.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau/American Community Survey

Access to healthcare is another factor to consider. In some cases members of the AI/AN communities drive an hour or more to reach a medical provider. This is further complicated by a lack of transportation on most reservations. The Indian Health Service (IHS) is underfunded and lacks medical providers, equipment and facilities to handle critical patients. It runs 24 hospitals, which have fewer than 71 ventilators and just 33 ICU beds.

So, are there COVID-19 racial disparities?

We know that the color of one’s skin doesn’t make a person more susceptible to COVID-19. But what we’ve seen from the data is that AI/AN communities are disproportionately affected because of other contributing factors. These same factors amplify the risk of COVID-19 among all communities of color.

This pattern of impact isn’t unique to COVID-19 — other diseases behave in much the same way. Instead, COVID-19 has placed a necessary spotlight on these issues because of its devastating effects. The data reaffirms that more research is needed —regarding inequality of healthcare access and how certain populations are affected by viruses like COVID-19. We need to increase society’s diligence to understand and address the unbalanced systems affecting communities of color. While the AI/AN population is often overlooked because of its small numbers, statistical insignificance doesn’t mean members of these communities are insignificant.

Other articles in this series:

- Comparing data across countries.

- Comparing data across time.

- Case fatality rate vs. mortality rate vs. risk of dying.

- Age isn’t everything.

COVID-19 misinformation causes, factors topic of segment

NLP’s Peter Adams discusses COVID-19 misinformation causes and contributing factors in an Aug. 31 segment for Northern Public Radio, What Contributes to COVID-19 Misinformation?

Some causes include a lack of understanding about the science involved in addressing a pandemic, the public’s inability to recognize the difference between fact-based journalism and opinion, the proliferation of news sites and postings that lack credibility, and consumers’ failure to identify credible information.

On the latter point, Adams says: “Trustworthy information doesn’t actually ask you to trust it. It shows you why you should.”

The segment was rebroadcast Sept. 1 on Peoria Public Radio (WCBU) and on All Things Considered on NPR affiliate WSIU.

Silva offers advice on navigating misinformation about COVID-19

John Silva, NLP’s senior director of education and training, talks about Navigating Misinformation in the Time of COVID-19 in Flipboard’s Aug. 19 educators blog. “What we don’t talk about enough is that while we are self-isolating and social distancing, we can’t maintain our social connections. So we are turning to social media to maintain those connections, and social media is where so much of this misinformation is so easily spread,” Silva notes. He offers simple steps and overall guidance for avoiding misinformation and determining the credibility of information and sources regarding the coronavirus and any other topic.

Podcast “Fighting Misinformation in the Age of COVID-19” features Adams

The EdSurge Podcast’s July 7 episode Fighting Misinformation in the Age of COVID-19 featured Peter Adams, NLP’s senior vice president of education. Adams stressed the real harm that health misinformation can do. He also shared simple steps anyone can take to stop the spread of falsehoods and hoaxes.

Understanding COVID-19 data: Age isn’t everything

This piece is part of a series, presented by our partner SAS, that explores the role of data in understanding the COVID-19 pandemic. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field. (Check out other posts in the series on our Get Smart About COVID-19 Misinformation page.)

As the United States enters its seventh month in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen myths created and debunked, fears and hopes elevated and dashed, and initial assumptions become lessons learned.

The most important piece of conventional wisdom proven false is that the virus targeted only older people and that younger generations were largely safe from infection. However, data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on June 19 tells a different story. As of May 30, 70% of those who tested positive for COVID-19 were under 60. In March, by comparison, approximately 25% of positive cases occurred in people under 50.

One theory for the surge of cases in those under 60 is that in the early days COVID-19 testing was restricted to only the sickest patients. Therefore, many people with mild cases — often those under age 65 — may not have been diagnosed. Regardless, the new CDC report underscores that younger generations are vulnerable to COVID-19 infections and can get very sick or die.

Yet, the elderly and those with certain chronic health conditions do remain most vulnerable to severe illness and death. Experts have been exploring questions about vulnerability and how to protect at-risk populations since an outbreak of 129 cases of COVID-19 among patients, staff and visitors resulted in 40 deaths at a Kirkland, Washington, nursing home in February.

COVID-19 risk factors about more than age

Initially, public health officials focused primarily on age when evaluating COVID-19 vulnerability. But the definition of vulnerability quickly expanded to include those with underlying health conditions like diabetes, asthma, cardiovascular disease, and obesity. We now know that individuals over age 65 who contract COVID-19 are more likely to develop severe complications not solely due to age, but also because they may also have underlying health conditions. This partly explains why 40% of U.S. deaths from COVID-19 have occurred in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities.

Knowing that age and underlying health conditions help determine the risk of vulnerability is important, but it doesn’t fully explain why so many cases occur in those facilities.

Other factors that aid in the spread of infectious disease may be present:

- Shortages of personal protective equipment like masks and gowns can hinder necessary precautions.

- Shared bedrooms and common living spaces among residents make it nearly impossible to effectively socially distance.

- Transfers of residents from hospitals and other locations can introduce exposure to disease.

- Frequent visitors, employees and other providers coming from outside the facility further increase risk.

Data makes the difference

Analyzing data about aging populations helps us better understand why these individuals are at greater risk for COVID-19. For example, we can use data to see where the most vulnerable populations are located and how they are impacted by the virus. When we look at the geographic distribution of population by age along with data on secondary conditions that may be present, we get a better idea of the dangers facing aging populations. This deeper knowledge reveals how contributing factors can lead to high susceptibility to COVID-19 and helps us understand how to protect these populations

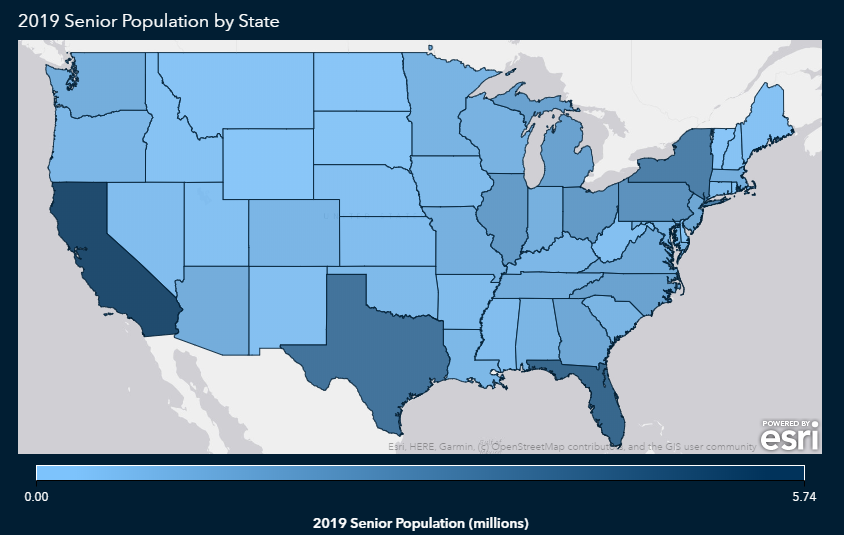

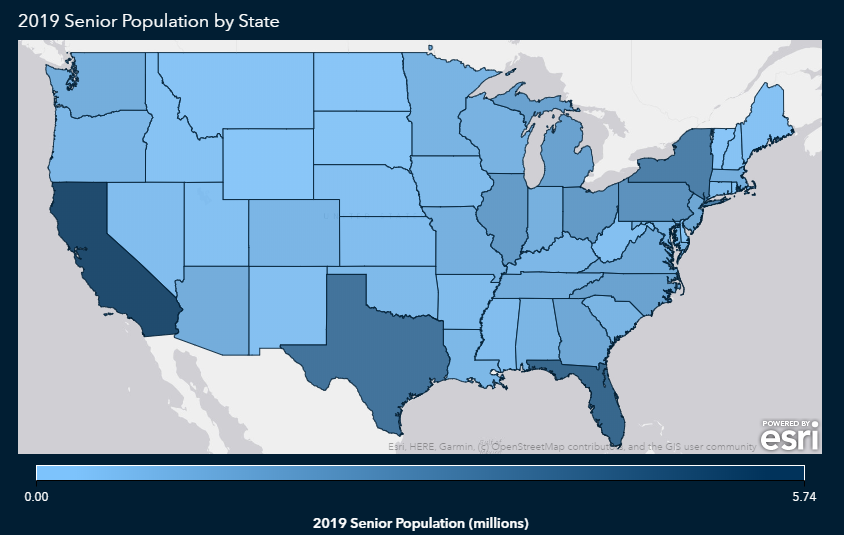

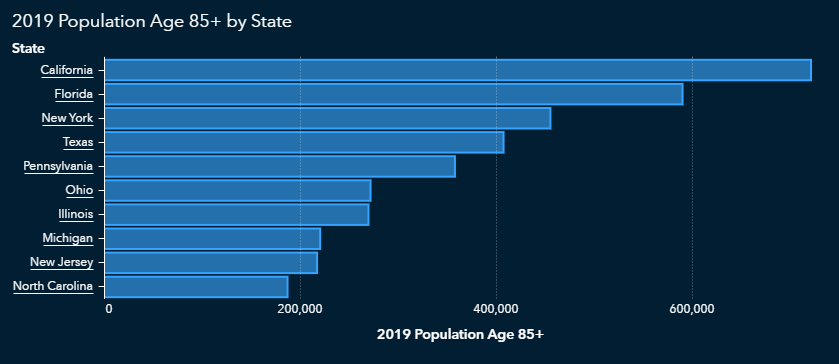

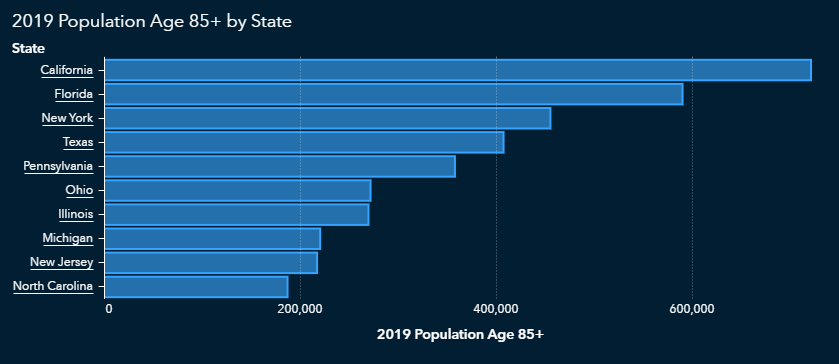

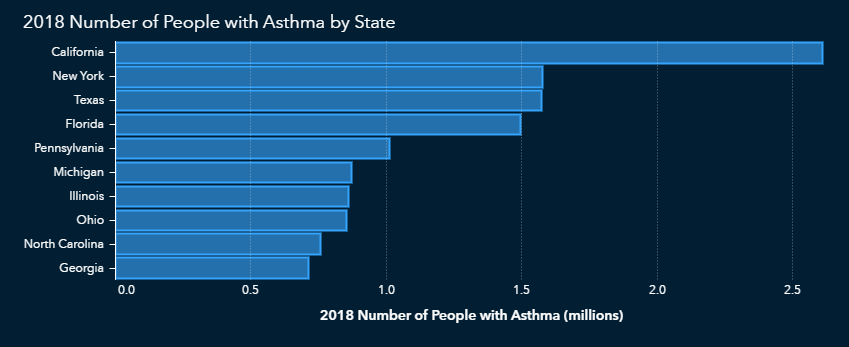

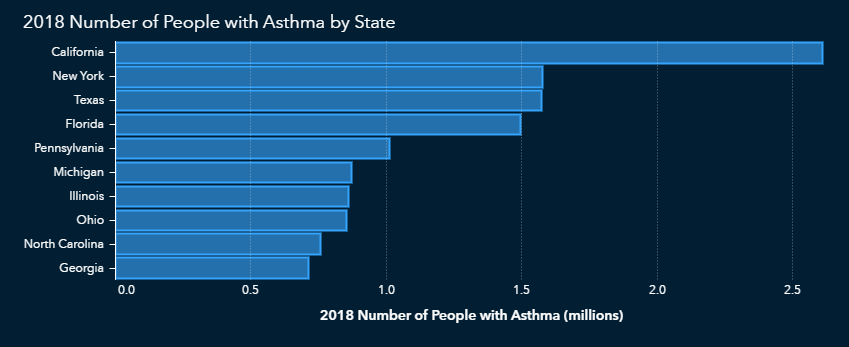

There are more than 50 million Americans over the age of 65. California, Florida, Texas and New York have the highest number of older Americans, with Sumter County, Florida, having the highest overall percentage in the nation.

As we might expect, those states also have higher concentrations of people over age 85, since that’s a subset of the 65-and-over population.

Do COVID-19 risk factors follow state lines?

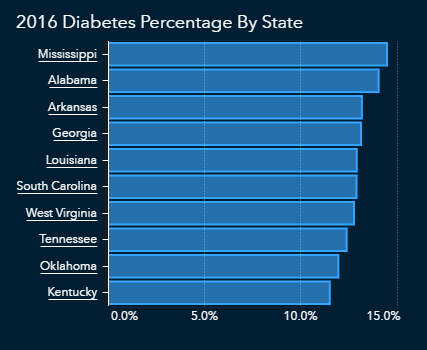

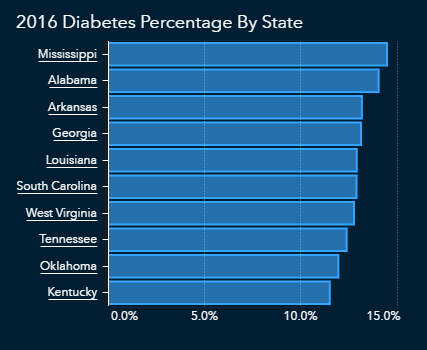

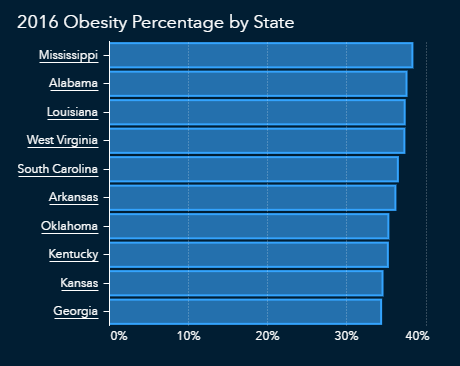

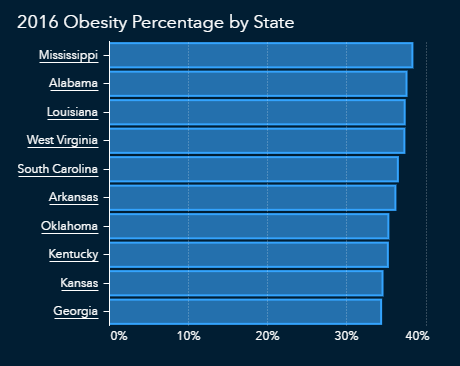

Obesity and diabetes often go together, and according to CDC data, the states most affected by obesity and diabetes overlap and tend to be concentrated in the southern United States.

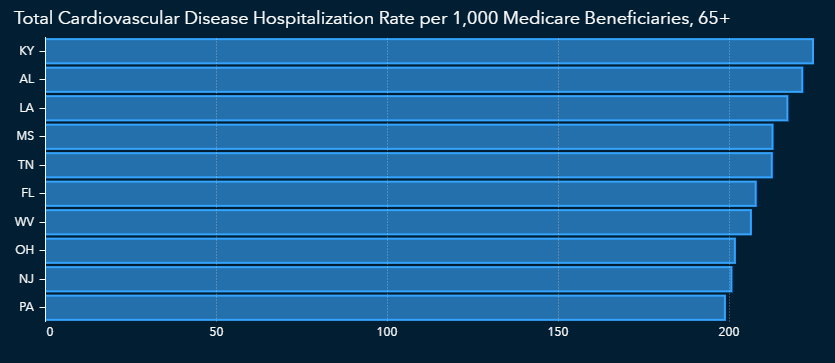

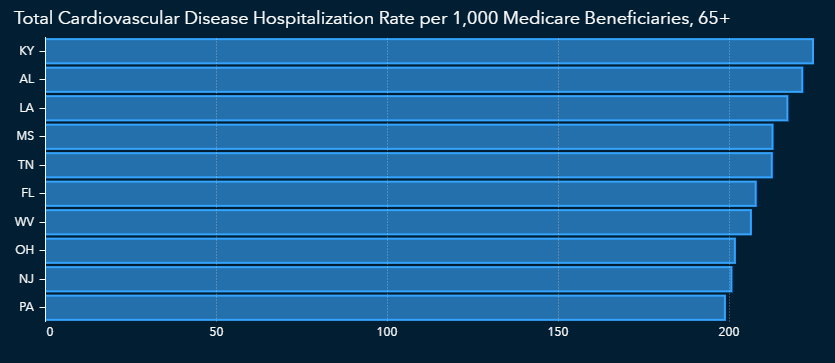

The CDC also reports cardiovascular disease in terms of hospitalizations, with a focus on those over age 65. The data shows an overlap with states that have higher numbers of diabetes and obesity. This could mean that those hospitalized with cardiovascular disease might also have diabetes and/or obesity, which would put them at even higher risk of severe complications from COVID-19.

Finally, we must look at data regarding lung conditions such as asthma. Some states with a high incidence of asthma cases overlap with those states that have large populations with at least one of the other risk factors we’ve examined.

What does all this mean?

The data appears to show that there are vulnerable people everywhere in the U.S., but there are concentrations in several areas. As states loosen restrictions initially put in place when the pandemic hit the U.S., it becomes important to evaluate population data within each state to ensure that those who are most vulnerable are protected. In recent weeks we have seen upticks in cases in some states that loosened restrictions.

It is crucial that we identify risk factors and set up proper safeguards. By evaluating additional risk factors and analyzing data within our own communities, we gain a more complete understanding of the COVID-19 impact. When we consider the whole individual, rather than age alone, we better understand what it means to be vulnerable during this pandemic and going forward.

Other articles in this series:

![]()

![]()

Georgia student sees impact of news literacy education

As the COVID-19 pandemic began delivering a surge of misinformation to our social media feeds and inboxes, a student in Denise Wood’s Honors World Literature and Composition class emailed her.

“I thank

Wood, an educator at Union Grove High School in McDonough, Georgia — outside Atlanta — teaches news literacy using the Checkology® virtual classroom. “I had become very concerned about the credulousness I noticed in my students. They often seemed to believe that if something was published, it must be true,” she says.

But she was not surprised to see Ahmad apply what he learned to critically assess information about COVID-19. “Afnan is a very committed student who is intensely curious about the world,” she says. He was definitely engaged (in Checkology) from the get-go. He asked questions in class and came up with several relevant examples.”

Ahmad says Checkology helped him to learn how to filter online content and be more discerning. “The unit really taught me how I should be aware of what I’m exposed to on Instagram and Twitter,” he says. “So much information is created to scare someone and instill hatred.” Previously, Ahmad said he assumed all news sources were credible.

And throughout this pandemic he has seen plenty of dubious content. “It’s a problem especially for more vulnerable populations,” Ahmad says. “A lot of family back in Bangladesh, where my parents are from, they don’t have the exposure to information we have. They might see a fake cure and believe that.”

Helping others

He also helps his parents view social media content with more skepticism. For example, regarding posts from impostor websites that mimic legitimate news outlets, he demonstrates the steps he follows to verify credibility. These include examining the source, checking for biases and considering them, and looking at how other sites report the same information.

And he does the same with peers, especially regarding COVID-19. “For the most part, I’m the one educating my friends about it. They are often surprised that everything they see is contradicted. It is hard to keep up with the information and the contradictions.”

Still, some of what Checkology taught Ahmad is less tangible. “It makes me have a sense of confidence that I’m looking at the correct post and correct source and can help my family and people around them.”

International perspective

Ahmad travels widely and brings an international perspective to his news consumption. “News stories in other countries focus on global news, but in the U.S. we focus on domestic news,” he says. “We have a focus on empowering ourselves.” Other countries focus internally, but also pay attention to what’s occurring around them, Ahmad observes. “It’s important for me to have all those perspectives.”

He also has a strong interest in propaganda, content that distorts and manipulates facts and information. Wood covers that topic in class. “I’ve combined the Checkology lessons with a larger unit on propaganda, which I connect with both current events and literature,” she says. “We usually use this concurrently with reading Animal Farm.”

And he said he is more attuned to spotting propaganda. “Now I know even a public announcement can be bias and propaganda. It’s not straightforward, and it can be subconscious in really subtle ways.”

And he expects to apply news literacy skills as he considers a career in medical research. “It has a grounding in what I’ve learned about information being credible.”

Educator relies on Checkology in class — and for teaching remotely

A few years ago Heather Turner, a teacher librarian in the Fabius-Pompey Central School District in central New York, saw social media posts from other librarians about Checkology® virtual classroom, and she was intrigued.

“I was looking for something to augment what I was already doing with digital citizenship,” says Turner, who has been an educator for a dozen years.

She then began using Checkology, NLP’s e-learning platform, in her classroom. “I teach media literacy in all of its facets so that my students are citizens who can discern the bias and information behind and about media,” she says.

Teaching remotely

And when the COVID-19 pandemic forced the closure of schools in Turner’s district earlier this year, she relied on Checkology as she transitioned to distance learning.

Perhaps surprisingly, she found similarities in online and classroom teaching. “I find that sometimes the students need a little bit of direct instruction as well as the videos and questions,” a major component of Checkology. She also supplemented Checkology’s 13 lessons with hyperdocs, which include comprehensive resource links, so the students can demonstrate their learning.

Two months into the COVID-19 education disruption, Turner has found that her students are adapting to the changes needed with distance learning. “They are doing much better now than when it first started,” she says.

But there are still challenges for students, educators and families, she notes. “I think we have to think of this as emergency school, not distance learning. This is not something students or staff signed up for and the stress has been hard for everyone.”

As COVID-19 continues to impact our lives, Turner said she is working to help students see the connections between the pandemic and the related “infodemic” of an overwhelming amount of information, much of it false and misleading.

Newsy piece looks at rise of QAnon conspiracy theory

In a May 21 segment for Newsy, QAnon Conspiracy Movement Gains Followers In Uncertain Times, NLP’s Darragh Worland discusses the rise of the far-right QAnon claims. The movement is based around the theory that President Donald Trump is bringing about a “great awakening” and will expose prominent political figures — the Deep State — for child abuse and political cover-ups. “Our democracy cannot really function the way it is supposed to in a world in which conspiracy theories are on equal footing in the marketplace of ideas with your credible information and reporting,” Worland says.

Education webcast, article discuss importance of critical thinking

Peter Adams, senior vice president of education at NLP, took part in the May 14 webinar Critical Thinking in the Age of Fake News hosted by the School Library Journal (SLJ) and the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE). He was joined by panelists Renee DiResta, research manager at Stanford University Internet Observatory, and Jennifer LaGarde, an educator and the co-author of Fact vs. Fiction: Critical Thinking Skills in the Age of Fake News. SLJ also posted the article The Importance of Critical Thinking in the Age of Fake News, based on the segment, to its website on May 19.

Critical Thinking in the Age of Fake News

Classroom connection: ‘Overwhelmed’ by information and misinformation

While 58% of Americans report being “well-informed” about COVID-19 and the virus that causes it, more than a third (36%) say they feel “overwhelmed” by the information (and misinformation) circulating about the pandemic: That’s a key finding from a new survey conducted by Gallup and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation as part of the Gallup/Knight Foundation Trust, Media and Democracy initiative.

The survey was conducted online between April 14 and April 20 with a random sample of 1,693 members of the Gallup Panel (a research panel designed to be representative of the U.S. adult population); the margin of error is plus or minus 3 percentage points. Results were published on May 11.

Other findings

- Almost 80% of respondents said that “false or inaccurate information about the coronavirus has been a major problem.”

- Almost half (47%) named “the Trump administration” as the primary source of misinformation about the pandemic; a third (33%) named “the mainstream national news.” But when respondents’ second choices were added in, “social media websites and apps” was the combined “winner” (the first choice of 15% and the second choice of 53%, for an overall total of 68%), followed by the Trump administration (the second choice of 7%, for an overall total of 54%).

- Respondents were evenly divided (42% for both) over whether social media platforms should immediately remove posts that are suspected of containing coronavirus misinformation or whether they should leave the posts up until the information in them is either confirmed or debunked.

In addition, younger adults (18-34) were more likely than older adults (55+) to say they are overwhelmed, though the reasoning for this was unclear.

Trust in news organizations played a part in responses, the survey found: Those with a favorable opinion of the media were “nearly twice as likely as those who view it negatively to say they are well-informed, 79% to 41%.

Classroom discussion

The World Health Organization describes the overwhelming spread of information — and misinformation — about COVID-19 as an “infodemic.” How would you describe your experience with this “infodemic”? How difficult is it to find credible information about COVID-19? How often do you encounter information that you’re not sure about? Where do you encounter questionable information? Have mainstream news outlets gotten anything wrong about the pandemic? If so, what was it?

Another idea

Have students review the Gallup report and replicate it by asking people 18 and older in their households the questions featured in the report. How do students’ results compare with the survey findings?

Classroom connection: QAnon conspiracy theory paved way for other hoaxes

Conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 pandemic can be described in a variety of ways — alarming, outlandish, dangerous — but they shouldn’t be surprising. Even the Plandemic “documentary” that suddenly swept its way across social media earlier this month did so on a path paved with fragments of pandemic conspiracy theories that were already in circulation.

But as a report by Adrienne LaFrance in the June issue of The Atlantic points out, if one theory has established conspiratorial thinking as an “acceptable” option in the modern marketplace of ideas, it’s QAnon.

Born in the aftermath of the Pizzagate debacle with two cryptic, anonymous posts published to the controversial message board 4chan in October 2017, QAnon has grown into a large and nebulous belief system. Its “leader,” known only as Q, is “a purportedly high-ranking government official.” At its heart is the baseless notion that President Donald Trump is secretly working to bring about a “Great Awakening” to expose an elite cabal of child sex abusers — including prominent political figures in Washington — that has been concealed by intelligence agencies, or “the deep state.”

QAnon conspiracy theory aims to simplify complex issue

In many ways, QAnon is a quintessential conspiracy theory: It offers its adherents simple explanations in place of complexity, a coherent entity on which to place blame for the transgressions of modern life, and a sense of control and populist purpose. But in other ways, it seems to have tapped into deeper veins of moral gratification: an apocalyptic vision of a renewed America that resonates deeply with evangelical Christian beliefs about the End Times. (Indeed, at least one church has been founded on QAnon belief principles.)

Whether they see QAnon as prophecy, as self-described “research” or as an “open source intelligence operation,” its followers have grown so numerous, and pushed its rhetoric so persistently on so many fronts online, that its most anodyne permutations — vague references to a coming reckoning for immoral Washington elites — are disturbingly present in mainstream discourse. They appear as Q icons and slogans at political rallies and are popularized by an increasing number of social media influencers and public officials.

Related

- “’Immune to Evidence’: How Dangerous Coronavirus Conspiracies Spread” (Marshall Allen, ProPublica).

- “I was a conspiracy theorist, too” (Dannagal G. Young, Vox).

Discuss: What are the characteristics of conspiratorial thinking? How can entirely baseless conspiracy theories “feel” so right to some people? What role does evidence play in conspiracy theories? Why do you think conspiracy theories tend to arise during periods of great social and economic change? How do fear and anger contribute to the belief in conspiracy theories?

Santa Fe misinformation program features NLP consultant

Damaso Reyes, a former NLP staff member now working as a consultant from Barcelona, Spain, discusses the current misinformation landscape in the May 19 segment of Here and There with Dave Marsh on KFSR, Santa Fe’s public radio station. It was Reyes’ fourth appearance on the program discussing news literacy issues.

‘Plandemic’ provides teachable moment for PBS segment

The viral conspiracy theory video Plandemic led to a wider discussion of how to identify credible news stories during a May 15 segment of Metrofocus, a program on WNET/New York Public Media. In an interview with reporter Jenna Flanagan, NLP’s John Silva explains how false stories gain traction and offered advice on how parents can model responsible news consumption habits. “If I was going to say something specifically to parents — and this is something I try to practice with my son — it’s that we need to practice these habits ourselves of fact-checking and verifying things … and modeling that for our kids,” he tells viewers.

Classroom connection: ‘Plandemic’ brings conspiracy theory mainstream

Purporting to be a preview of an upcoming “documentary,” Plandemic relies on a single source — Judy Mikovits, a discredited scientist — to vaguely contend that a powerful cabal of public health officials and others is exaggerating the current outbreak and seeking to exploit it for profit. Mikovits also makes a number of demonstrably false medical statements, including that wearing a mask “activates” viruses that people might be carrying and that “healing microbes” in seawater and “sequences” in sand can boost immunity.

The video, posted May 4, garnered more than 8 million views and hundreds of millions of engagements on social media before YouTube, Vimeo and Facebook started to remove it three days later. Produced by filmmaker Mikki Willis, whose Ojai, California-based production company, Elevate Films, creates “transformative media,” Plandemic positions Mikovits as a victim-turned-whistleblower, presenting a highly misleading and one-sided account of her career that includes a number of accusations made against Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and a member of the White House Coronavirus Task Force.

Falsifield details

It paves over the retraction in 2011 of a controversial study of chronic fatigue syndrome that Mikovits had co-authored two years before; it also falsifies details about her arrest in 2011 on two charges related to the theft of a computer, flash drives and other materials from the Whittemore Peterson Institute in Reno, Nevada, where she had worked as research director. (The charges were dropped.)

Footage of the interview with Mikovits, who in recent years has been an outspoken critic of vaccinations, is interspersed with a number of video segments that seem to bolster her claims but are actually highly misleading or unreliable. The b-roll footage includes out-of-context clips of Fauci, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates and other public figures; a portion of a report from CGTN, the Chinese state global news network; and several clips of people in medical scrubs calling into question the scientific consensus about the pandemic, including YouTube footage of Eric Nepute, a St. Louis chiropractor who suggested that the quinine and zinc in tonic water could treat COVID-19. Also prominently featured is footage from an April 22 press conference held by two physicians, Dan Erickson and Artin Massihi, who own urgent care facilities in Bakersfield, California, and have made a case to reopen California based on deeply flawed statistics.

Note: While the viral spread of Plandemic was aided by its slick production values and slippery sourcing, it also stitched together a number of baseless conspiratorial claims — anti-vaccination rhetoric, misinterpretations of COVID-19 Medicare payments to hospitals, possible COVID-19 treatments such as hydroxychloroquine, and the complicity of tech platforms — that felt familiar to a broad number of people who had already seen them online.

Related

- “I’m an Investigative Journalist. These Are the Questions I Asked About the Viral ‘Plandemic’ Video.” (Marshall Allen, ProPublica).

- “Why It’s Important To Push Back On ‘Plandemic’—And How To Do It” (Tara Haelle, Forbes).

- “The Falsehoods of the ‘Plandemic’ Video” (Angelo Fichera, Saranac Hale Spencer, D’Angelo Gore, Lori Robertson and Eugene Kiely, FactCheck.org).

- “Virus Experts Aren’t Getting the Message Out” (Renée DiResta, The Atlantic).

- “How covid-19 conspiracy theorists are exploiting YouTube culture” (Abby Ohlheiser, MIT Technology Review).

Discuss: What made Plandemic spread so widely so quickly? Were social media platforms correct to remove it? Why might a video like this — offering a simple explanation and a focal point for blame — appeal to so many people right now? What other conspiracy theories do this?

Idea: Have students share their stories of seeing Plandemic go viral last week, and ask whether they still have questions about points it raises. Work together to seek credible sources to answer those questions.

Parents find that Checkology enhances daughter’s distance learning

Not long after schools closed in Jackson, Wyoming, in March due to COVID-19 health concerns, Charlotte Krugh found that her daughter, Julia, 11, had too much free time on her hands. The sixth-grader’s distance learning assignments occupied her about three hours a day. Her sister Eliza, 9, who attends a different school, had a full day of work.

Krugh and her husband Brad were unhappy with how much time Julia spent watching YouTube videos while they were busy working from home. So they began to look into resources that would be meaningful and that Julia also might enjoy.

“We wanted something that would keep her engaged and not be busy work,” Krugh says.

That’s when she discovered that the News Literacy Project was offering its Checkology® virtual classroom free to U.S. educators and parents in response to school closures.

“At first she didn’t want to do it,” says Krugh, who, a former teacher well familiar with students’ resistance to additional work. “Then last week, she started to get into it.”

‘Aha!’ moments in distance learning

After a few lessons, Julia made some discoveries. For example, she had never given much thought to propaganda — a category of information in the InfoZones lesson. And she gained a new perspective on the YouTube crafting channel she watches. Krugh had told Julia that her favorite crafter might be getting paid to feature some of the products used in her videos, but she dismissed that idea. After completing a Checkology lesson that discussed sponsored content, Julia changed her mind. She told her mom: “You know, she might want to be trying to sell me something.”

Julia Krugh, 11, works on a Checkology lesson. Photo courtesy of Charlotte Krugh

“She is learning and we’re really pleased,” says Krugh.

And Julia wasn’t the only one in the family benefiting from distance learning. “One of the things that surprised me, I feel like I am pretty news savvy, but I got a few things wrong,” Krugh says. She was referring to the Checkology lesson on Branded Content that describes how some blog posts are actually deftly disguised advertisements. “I think there is something we all can learn from it.”

With that in mind, she also might introduce Eliza to Checkology. And she hopes to engage the group of friends Julia has virtual lunch with most days. “I’m hoping that some of her friends might be interested in it. It would be fun to have them do it,” Krugh says.

In the context of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic also provides opportunities for Julia and Eliza to broaden their perspectives, based on diverse sources of information. They take part in video calls with a great aunt who is an infectious disease doctor and stay in touch with friends they made in Spain, where the family once lived. That country has been hit hard by COVID-19, and the girls’ friends have been allowed outside to play only recently after many weeks indoors.

And a slide presentation that Eliza worked on provided a chance to discuss the validity of sources for COVID-19 information the friend provided. “I think that having a variety of ideas inform you is super important,” Krugh says. “It gives us an opportunity to talk about different ideas and where they come from.”

That’s also a basic tenet of news literacy education. This resonates with the family.

“We are not teaching critical thinking skills early enough. Anything we can do to improve academic success and beyond, we should be doing,” Krugh says. “We want our kids to question and wonder and be curious.”

Pandemic misinformation, NLP tips topic on South Carolina public radio

South Carolina Public Radio’s May 7 program, An Rx for BS: A Look at Media Literacy in Crisis Mode, focuses on the hazards of encountering COVID-19 pandemic misinformation and disinformation —much of it dangerous. The program includes tips from the News Literacy Project for identifying potential red flags when scrolling social media, or anywhere a person might consume information.

Classroom connection: YouTube search results to include fact-checker information

YouTube users in the United States will soon see information panels from third-party fact-checkers at the top of some search results, the company announced on April 28, citing the rapid spread of misinformation about COVID-19. The panels will appear in searches for specific claims and will feature relevant articles from “an open network of third-party publishers” of fact checks.

More than a dozen U.S. fact-checkers are already involved, the company said. These include FactCheck.org, PolitiFact, The Washington Post’s Fact Checker and The Dispatch. Participants must use the ClaimReview tagging system, a protocol developed by Duke Reporters’ Lab that extracts key details from fact checks so they can be displayed on other platforms. (Bill Adair, creator of PolitiFact, is head of Duke Reporters’ Lab.) Fact-checkers must be what YouTube calls an “authoritative publisher.” This is what YouTube considers an “established and relevant” source whose “expertise and trustworthiness” have been evaluated by external raters. Otherwise, fact-checkers must be verified signatories of the code of principles of the International Fact-Checking Network.

YouTube said its systems “will take some time” to “fully ramp up.” It piloted this feature in Brazil and India last year and plans to expand it to more countries over time.

Donation to fact-checking network

The announcement also said that the Google-owned video platform’s Google News Initiative is donating $1 million to the International Fact-Checking Network. The network is based at the Poynter Institute, a journalism training and advocacy center in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Also note: Citing violation of “community guidelines,” YouTube removed a widely disseminated video of a April 22 press briefing by two California doctors, Daniel Erickson and Artin Massihi. They used results from more than 5,000 COVID-19 tests conducted at their Bakersfield-area urgent care centers and private testing site to argue that shelter-in-place orders and business shutdowns are no longer needed. Erickson urged reporters to check with emergency doctors, who, he said, would support their conclusions. However, the American Academy of Emergency Medicine and the American College of Emergency Physicians condemned their remarks. They said “as owners of local urgent care clinics, it appears these two individuals are releasing biased, non-peer reviewed data to advance their personal financial interests without regard for the public’s health.”

Ask students:

Do you think YouTube’s move to highlight fact-checked articles in searches will help slow the spread of misinformation on its platform? Why or why not? What else could YouTube do to combat the spread of falsehoods?

Test the new feature

Once this feature is live, have students test it by searching for a specific COVID-19 claim. The company’s announcement uses “covid and ibuprofen” as an example. Ask them to provide a short summary of their experience. It should include the claim they searched, their search results, and whether a fact check appeared above the results. Then ask them to do the same search on other sites (such as Google, Bing, Yahoo, Twitter, Facebook and Pinterest). Finally, ask students to evaluate which is best at highlighting credible, authoritative information and demoting misinformation.

Classroom connection: Exploring the ‘Verification Handbook’

The European Journalism Centre, a journalism training and advocacy nonprofit in Maastricht, Netherlands, has released the third edition of its Verification Handbook, an online primer designed to help journalists investigate online content. The guide is edited by Craig Silverman, the media editor at BuzzFeed News and a digital fact-checking pioneer, and includes contributions from a range of distinguished journalists and misinformation researchers.

The book is divided into three parts: an introduction, which explains the stakes of digital verification work; a section on investigating individual accounts and pieces of content; and a section on analyzing platforms and influence operations.

Though it was created to help journalists avoid being exploited by “coordinated and well-funded campaigns to capture our attention, trick us into amplifying messages, and bend us to the will of states and other powerful forces,” the book is also broadly useful for anyone interested in honing digital verification skills — especially educators working with students.

Every article addresses a vital topic; several stand out for adoption in the classroom:

- “The Age of Information Disorder” by Claire Wardle, the head of strategic direction and research at First Draft. It includes three important elements for students: a taxonomy for categorizing different types of misinformation; an explanation of approaches to the thorny topic of determining the intent behind a piece of misinformation; and a graphic — the Trumpet of Amplification — that shows how bad actors “use coordination to move information through the ecosystem,” promoting falsehoods in closed groups and conspiracy communities until they trend on social media and gain the attention of professional media.

- Idea: In groups or individually, ask students to collect 10 recent examples of misinformation (by using fact-checking websites or this newsletter’s viral rumor rundown). Then have them trade those examples with another group or student and determine which of Wardle’s seven forms of information disorder best fits each example.

- “Spotting bots, cyborgs and inauthentic activity” by Charlotte Godart and Johanna Wild, two open-source investigators affiliated with the online investigations collective Bellingcat. It offers an approachable yet detailed look at automated and semi-automated accounts. This section also gives clear steps anyone can take to investigate suspicious accounts; explains common red flags for automated accounts; and links to several useful online tools, including three — Botometer, Bot Sentinel and accountanalysis — that analyze Twitter accounts for bot-like patterns.

- Idea: Review with students the common characteristics of automated accounts on Twitter, such as usernames that the platform automatically assigns, a lack of a profile picture, and unusual account activity. Have them work in teams to collect a number of accounts that they suspect are bots. Then have the teams trade their collections and use one of the free analysis tools linked above to evaluate the likelihood that the accounts are automated.

- “Investigating websites,” by Craig Silverman. It explains how to explore who is behind a website; how to uncover networks of shady sites; how to analyze web content (including webpages that have been deleted); how to use tools such as BuzzSumo and CrowdTangle to map the spread of specific links or domains across social media; and how to investigate domain registrations and IP addresses using tools such as DomainBigData.

- Idea: Ask students to read this article, then divide them into groups. Give each group a different tool mentioned in this piece; ask them to explore it, and then explain it, to their classmates.

NLP resource

Check Center, part of NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom, includes tutorials and fact-checking missions for students. (Registration is required for teacher or parent access; NLP is currently waiving new student license fees for those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Teachers and parents engaged in distance learning or homeschooling as a result of school closures can apply here for access through June 30.)

Miller calls for press freedom during the pandemic in CNN op-ed

Classroom connection: COVID-19’s impact on press freedom

The next decade is critical for the future of journalism, and the COVID-19 pandemic is deepening existing crises that already threaten free and independent reporting, Reporters Without Borders said April 21 as it released its annual World Press Freedom Index, which ranks 180 countries and regions on the level of freedom they afford journalists.

Christophe Deloire, secretary-general of the global media advocacy organization (also known as Reporters sans frontières, or RSF), said that the pandemic is exacerbating “the negative factors threatening the right to reliable information”: a geopolitical crisis, a technological crisis, a democratic crisis, a crisis of trust and an economic crisis.

In its overview of the rankings, RSF noted “a clear correlation between suppression of media freedom in response to the coronavirus pandemic and a country’s ranking.” China (177th) and Iran (173rd) censored information about the spread of COVID-19, RSF said.

The director of RSF’s London office, Rebecca Vincent, rebuked the Chinese government for its lack of truthful reporting when it first had the opportunity to provide information.

“If there had been a free press in China, if these whistleblowers hadn’t been silenced, then this could have been prevented from turning into a pandemic,” she told CNN Business. “Sometimes we can talk about press freedom in a theoretical way, but this shows the impact can at times be physical. It can affect all of our health.”

A spokesman for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Geng Shuang, dismissed RSF’s criticism, saying that the organization “has always held deep-rooted prejudice against China” and its report “is not worth rebutting.”

USA not number one

The United States was 45th this year in the RSF rankings, an improvement of three places from 2019. Norway ranks first, as it has since 2017, and North Korea dropped one place to become the least free country, as it was in 2018 and 2017 (Turkmenistan occupied last place in 2019). Due to change brought about by general elections in May 2018, Malaysia had the largest improvement (22 places) to 101st, while Haiti — where protesters have targeted journalists — experienced the most significant drop (21 places) to 83rd.

While RSF’s “global indicator” — its measure of the overall state of press freedom — improved by 0.9% in 2020, it has declined by 12% since its creation in 2013. According to that indicator, press freedom is in a “very serious situation” in 13% of the countries and regions around the world, an increase of 2 percentage points from 2019.

For discussion

What makes the press in a given country “free”? Why is freedom of the press important? How does the level of press freedoms in the United States compare with what is found other countries? What role does a free press play in democratic societies?

Activities for students

Ask students to guess which countries around the world have the greatest and least amount of press freedoms. Then have them research their hypotheses using Reporters Without Borders’ 2020 rankings. Finally, help them contact a journalist in one of the countries they researched so they can ask questions by email or request a brief videoconference.

NLP resource

Press Freedoms Around the World” (NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom). Note: This lesson will be updated with the 2020 rankings this summer.

Newsy segment covers pandemic’s effect on press freedoms

In Newsy’s April 30 segment on the coronavirus and misinformation, COVID-19 Limiting Press Freedoms, NLP’s Darragh Worland notes that the pandemic has empowered some governments to censor information or crack down on reporters trying to cover the crisis.

Classroom connection: New transparency measures at Google, Facebook

Both Facebook and Google have announced new transparency measures intended to give users more information about who is behind the posts and ads they see. In an April 22 Facebook Newsroom post, Anita Joseph and Georgina Sheedy-Collier, product managers for Facebook and Instagram (owned by Facebook), said that the platforms will be providing “the location of high-reach Facebook Pages and Instagram accounts on every post they share.” The following day, John Canfield, Google’s director of product management and ad integrity announced that beginning this summer, the company will require all advertisers on its platforms — including those using the Google AdSense program, which places targeted ads on almost 11 million websites across the internet — to provide “information that proves who they are and the country in which they operate.”

Joseph and Sheedy-Collier said that the new feature would be piloted in the United States, starting with “Facebook Pages and Instagram accounts that are based outside the US but reach large audiences based primarily in the US,” though they didn’t specifically define what was meant by “high-reach.” Canfield said that Google would start by verifying information for advertisers in the United States before expanding the program worldwide, noting that that this initiative would take years to complete.

The world’s largest social media company and the world’s most popular search engine have introduced a variety of measures to improve transparency since their platforms were used by state-sponsored disinformation agents seeking to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election (PDF).

Take note

Despite an announcement by Facebook in February that it had banned ads for products that claim to cure or prevent COVID-19, and a post from its chairman and CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, on April 16 stating that “harmful misinformation” about COVID-19 will be taken down, two investigations last week found evidence that neither of these policies is being consistently enforced. An April 23 report in The Markup discovered that Facebook’s Ads Manager — which makes it easy for advertisers to target extremely specific groups of users — offered an audience segment of people interested in pseudoscience. An April 24 NBC News investigation found active Facebook ads promoting ultraviolet lights for medical treatments that violated the platform’s COVID-19 misinformation policy.

In addition, a search on Facebook on April 27 for “Miracle Mineral Solution” — a dangerous form of bleach hyped as a “cure-all” — showed that there are at least one page and two groups dedicated to promoting the toxic solution. (At the COVID-19 briefing with reporters on April 23, President Donald Trump suggested evaluating the use of ultraviolet light and “disinfectant” inside patients’ bodies for their effectiveness in treating COVID-19.)

Related reading

“Google Will Require Proof of Identity From All Advertisers” (Tiffany Hsu and Daisuke Wakabayashi, The New York Times).

For discussion

What impact do you think these transparency measures will have? Should Facebook and Google have taken these steps sooner? How challenging is content moderation for tech companies? Are there transparency features and tools that should (but don’t) exist on major social media and digital advertising platforms? What are they? What other kinds of tools could social media platforms add to help their users better understand what they see?

Another idea

Review with students the existing transparency features on Facebook, including its page transparency section and its instructions on viewing the data the platform has collected about them, and Google’s “Why This Ad?” link and data profile tools.

NewsLitCamp, NLP resources make a difference

Georgia educator Erin Wilder at a NewsLitCamp in Columbia, South Carolina, in January 2020. Photo by Miriam Romais / The News Literacy Project

Earlier this year – back in the days before the U.S. largely shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic – we held a NewsLitCamp® in Columbia, South Carolina. In attendance was a team of educators led by Erin Wilder, who had driven nearly three hours and 200 miles from Hoschton, Georgia, to be a part of that day’s professional development session.

When we heard that, we knew we had to find out more: Why was it so important for her and her team to be there?

“I’ve been preaching NLP for years,” Wilder told us in a recent interview, “but I told my team you have to go see them in-person to get the whole picture. So our principal gave us the day off, and we drove over and got a lot of great new information and ideas. We just gabbed and gabbed on the drive back and shared ideas and started making plans so that we could better help our kids understand everything about news literacy.”

One of the key NewsLitCamp takeaways for Wilder was lateral reading.* “We realized we had to have kids go to different sites and look at how those sites present similar ideas. Typically, kids will just see one side of the news. And that’s good because we’re not trying to force an opinion on them. We just wanted them to see how different sides approach a topic and then let them develop their own consensus about it.”

What the kids need to become adults

Wilder has been teaching high school English for 17 years and has been at Mill Creek High School for the last eight. She says that in recent years she has realized that in addition to the standard reading and writing curriculum, some newer skills and tools were needed to help them leave high school armed to be literate citizens as well. As a result, her team decided to take the last few weeks of their language arts program to “get them ready for the world.”

That process took a big jump forward when she watched a webinar led by Peter Adams, NLP’s senior vice president of education, and John Silva, NLP’s director of education. She remembers thinking, “This is so great, we need to do this,” and she began using the first generation of the Checkology® virtual classroom. “I had to get permission to circumvent the firewall, and we started doing the lessons once a week in the computer lab,” she told us. “The students absolutely loved the Checkology lessons. They would sit at their computers and go at their own pace. It was my first foray into adding news literacy lessons for them and they enjoyed it, and I loved the work we were getting back from them.”

Overall, she adds, “They felt it was so much more valuable and applicable to their lives and what they felt they needed going out into the world. They realized they have so much digital contact, but didn’t have the internal ability to process it. But they’ve really enjoyed getting these tools to build a better understanding of what’s going on.”

Using The Sift during COVID-19 pandemic

Around early March, Wilder says she began hearing more and more people talking about drinking bleach or snorting cocaine as a cure for COVID-19. And she realized right then, “This is what we’re studying. I took a bunch of articles and put them together and went in to show everyone that we are literally living in this moment of harmful misinformation and that’s why we have to learn these news literacy skills.

“And then the next issue of The Sift® came and it had great stuff in it – lots of great ideas. It’s easy to tell kids misinformation is out there, but it can be hard to show an example. The Sift gave us a lot that we can actually show them. I started using that issue to pull sample articles and posts to create a two-day activity where the kids could look at all these different rumors that were spreading and what fact checking sites had to say about them. And then they said, ‘OK, we’re closing schools’ and that was the last thing we got to do with them face-to-face. But it was so rewarding to see the kids applying the skills we have been working on to something that was so current.”

In the end, while Wilder is disappointed that schools are closed and she won’t be able to finish using Checkology with her students, she plans to continue using all of the tools that NLP provides. And with a little luck, she said she’s dedicated to, “trying to make a NewsLitCamp happen in Atlanta. I’m hoping to work with you on that.”

*The lateral reading concept and the term itself developed from research conducted by the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG), led by Sam Wineburg, founder and executive director of SHEG.

Apple News adds How to Know What to Trust in COVID-19 guide

Under the heading, Tried-and-true tactics to help spot bogus claims, no matter the subject, Apple News Spotlight includes NLP’s easy-to-follow guidelines, How to Know What to Trust, in its comprehensive guide to COVID-19 misinformation.

COVID-19 and kids: Newsy looks at resources to aid understanding

NLP resources and initiatives are included in an April 24 Newsy piece regarding COVID-19 and kids. The segment, Kid-Centered News Shows Aim To Help Children Understand COVID-19, also quotes NLP’s Peter Adams.

COVID-19 and Bill Gates conspiracy theories topic of second segment of Newsy series

COVID-19 and Bill Gates conspiracy theories are the topic of the second installment in a weekly series for Newsy featuring the News Literacy Project. Darragh Worland, NLP’s vice president for creative services, discusses how conspiracy theories linking the COVID-19 pandemic and Bill Gates have gained traction and become wildly popular across social media despite having been widely debunked.

“Public figures in general are easy targets for conspiracy theories,” Worland tells Newsy viewers in the April 24 segment.

According to the segment, people mentioned false conspiracy theories on social media that incorrectly linked Bill Gates to coronavirus 1.2 million times between February and April. The theories, Worland says, were created out of selective manipulation of information on Gates.

“Their research is just leading them down all these paths and their mind is making connections that really are not there,” Worland says. “Ultimately these kinds of conspiracy theories can affect people’s civic life, they can affect the decisions that they make.”

Newsy is an online national news network owned by The E.W. Scripps Co., which joined NLP in presenting National News Literacy Week in January as part of our ongoing partnership.

Healthy living website taps NLP for ‘infodemic’ advice

John Silva, NLP’s director of education, offers advice and tips for Well+Good’s audience as they navigate misinformation swirling around the coronavirus. The April 22 piece Why social media has helped turn COVID-19 into an ‘infodemic’ includes interviews with public health and media literacy experts.