News literacy skills help student better understand harm of bias, misinformation

Ana Rodriguez

2021 Gwen Ifill High School Student of the Year

Archie Williams High School

San Anselmo, California

Like many teens, Ana Rodriguez, 15, turns to social media to find out what is going on in the world. But she is well aware that sorting fact from fiction in her newsfeed can be difficult.

Like many teens, Ana Rodriguez, 15, turns to social media to find out what is going on in the world. But she is well aware that sorting fact from fiction in her newsfeed can be difficult.

“As a Latino woman in society, it is fundamental for me to have the right information at all times. We sometimes are not provided with the right concepts on certain topics because of detrimental biases that affect the way my community is perceived,” she told NLP.

This awareness motivated Rodriguez to learn how to think critically about the information she consumes and shares. And she got that chance when her English teacher Matthew Leffel, who nominated her for the Gwen Ifill High School Student of the Year Award, introduced his 10th-graders to Checkology® this past school year.

“A few years ago, I wouldn’t have checked my sources or the sources the articles that I’m reading about come from, but now I would definitely do that because I don’t want to be sharing false information to the people around me,” she said.

Leffel noticed immediately how the news literacy concepts resonated with Rodriguez. “There is an unmistakable spark in a student’s countenance that appears when they have decided to grab hold of their learning. Even in a classroom mediated by distancing guidelines, I could see it in Ana’s masked face in English class as we began an interdisciplinary project that focused on challenging pseudoscientific claims,” he said.

Learning about bias and misinformation helped Rodriguez complete that project, which explored pseudoscience, and more specifically, racism in science. She examined the long and harmful history of racial bias in scientific thinking, from eugenics to contemporary medical discrimination.

“For the project, I had to research several pieces of information that provided reliable facts and supported data, as well as researching those who did not provide effective information,” Rodriguez wrote in her essay for NLP. “In our world, almost every situation we choose to participate in is based mainly on the information we acquire from it.”

“Being able to distinguish reliable information from detrimental bias has been of great importance in my life. It has allowed me to help my parents and other family members during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Rodriguez said, noting that she was able to advise her family how to steer clear of misinformation about vaccines.

“I want my community as well as many others to have the opportunity to learn about the dangers of biases that connect our world, as I want everyone to understand the consequences that manipulated stories and concepts can lead to,” she said.

In nominating Rodriguez, Leffel described her as a “fiercely dedicated student” who holds herself to high standards and often pushes herself beyond them.

Being named NLP’s high school student of the year has bolstered her belief in herself. “It has given me the sense that I accomplished something very big, and that I can be successful with the things that I do. Like a kick of confidence, I would say.”

The award commemorates Ifill, the trailblazing journalist — and longtime NLP supporter and board member — who died in 2016. It is presented to female students of color who represent the values Ifill brought to journalism. Ifill was the first Black woman to host a national political talk show on television as moderator of Washington Week, and she was a member (with Judy Woodruff) of the first female co-anchor team of a national news broadcast, on PBS NewsHour.

In this video Rodriguez explains why news literacy is important to her.

Related Stories:

- Celebrating News Literacy Change-Makers

- NLP honors 2021 News Literacy Change-Makers

- NLP’s Journalist of the Year has witnessed harm misinformation can inflict

- Educator helps integrate news literacy across disciplines

- Student gains knowledge, confidence to help stop misinformation’s spread

- Meet our impressive student of the year finalists

Student gains knowledge, confidence to help stop misinformation’s spread

Mirudulaa Suginathan Yamini

2021 Gwen Ifill Middle School Student of the Year

Central Middle School

Quincy, Massachusetts

Mirudulaa Suginathan Yamini, 13, always had assumed that misinformation did not affect her. Then last year, when she was in seventh grade, she learned firsthand how it could fool her and just how fast and how far it can spread.

Mirudulaa Suginathan Yamini, 13, always had assumed that misinformation did not affect her. Then last year, when she was in seventh grade, she learned firsthand how it could fool her and just how fast and how far it can spread.

“I read a really interesting post and sent it to so many of my friends. But when I was reading it for the 10th time or so, I realized it wasn’t real news. It was fake,” she told NLP.

She immediately tried to stop the falsehood in its tracks. “I had to tell all the friends I’d sent the post to stop spreading it and why it’s not credible and not reliable,” Mirudulaa said. “But it was already too late. They sent it to their friends and so on.”

That’s when she realized just how hard it is to stop the spread — and potential harm — of misinformation. “I didn’t have any of the tools to see if it was real, or even learn about how to see if it’s real,” she said.

It was a hard lesson. “I felt very upset that now, I just told my friends things that are not true. And I was kind of really disappointed in me.”

But she would soon learn how to avoid being fooled next time.

When she entered eighth grade, school librarian Helen Mastico introduced Mirudulaa and her classmates to NLP’s Checkology® as part of a media class. Mirudulaa learned how to discern credible information from rumor, conspiracy theories and manipulated content. Now, she never shares information that she has not verified as reliable. And if someone sends her content that she recognizes as misinformation, she lets them know and advises them to explore Checkology.

When nominating Mirudulaa for the student of the year award, Mastico, wrote that “Mirudulaa is an intelligent, dedicated, and conscientious student. Her tenacity at getting to the root of an issue is impressive, and I believe she deserves the award in recognition of that drive. Like a good journalist, she is thorough and attentive to detail, whilst retaining a compassionate attitude and a good idea of the bigger picture.”

The award commemorates Ifill, the trailblazing journalist — and longtime NLP supporter and board member — who died in 2016. It is presented to female students of color who represent the values Ifill brought to journalism. Ifill was the first Black woman to host a national political talk show on television as moderator of Washington Week, and she was a member (with Judy Woodruff) of the first female co-anchor team of a national news broadcast, on PBS NewsHour. She will receive a $500 gift certificate and a glass plaque with an etched photo of Ifill.

Mirudulaa, the first middle school student to receive the award, said she feels empowered by her news literacy lessons. “After using Checkology I feel a lot more informed and confident because I can actually see which is fake and which is not fake. Checkology helps you improve, realize and change your ways.”

She tries to regularly share her Checkology knowledge with her fellow students, and even beyond the classroom. “I showed my parents many of the tools I saw in Checkology. Even they felt it was a big impact on their life. They changed. They stopped viewing some of the websites that they thought they could rely on,” Mirudulaa said. And, she added, they were even more proud of her than before.

Watch this video to hear Mirudulaa discuss the importance of news literacy in her own words.

Related Stories:

- Celebrating news literacy change-makers

- NLP honors 2021 News Literacy Change-Makers

- NLP’s Journalist of the Year has witnessed harm misinformation can inflict

- Educator helps integrate news literacy across disciplines

- News literacy skills help student better understand hard of bias, misinformation

- Meet our impressive student of the year finalists

Meet our impressive student of the year finalists

This year we had an abundance of strong submissions from so many amazing students that it was difficult to choose just one winner in each of the categories — high school and middle school. While we felt that all the students deserve kudos for their hard work, we want to highlight two students — our high school and middle school Gwen Ifill Student of the Year finalists. Congratulations to Grace Min and Kyrie M. Blue!

Grace Min

Finalist, 2021 Gwen Ifill High School Student of the Year

Canfield High School

Canfield, Ohio

Studying news literacy has had a truly powerful and personal impact on Grace Min, 15. In the essay she submitted to NLP, she told us that becoming more news-literate allows her to navigate the world with less fear and more confidence.

“The world is a scary place filled with uncertainty and lies, or at least that’s what we’re told growing up. But in reality, the world is far less scary when you are able to recognize truths from lies,” the 10th-grader wrote.

Being able to recognize fabrications and distortions about her community and her identity came as a revelation, which she described with honesty. “Growing up a woman of color in a predominantly white area, I wasn’t able to recognize truths from lies as easily as I would have wanted to. Unfortunately, at a very young age, I became subject to both blatant and subtle racism. My own racial identity changed into [something] that I despised about myself,” she wrote. “It wasn’t until I discovered news literacy education that I was able to understand that all of the racism I faced were lies. Doing my own research, finding credible sources and being able to create my own opinions was a liberating shift.”

Min’s English teacher, Chris Jennings, who nominated her for the student award, is not surprised at her depth of understanding and her ability to connect news literacy concepts to her place in the world. “Every once in a while —maybe once or twice a year, and sometimes less often — a student comes into my life and completely validates my decisions to become an educator. Grace Min is one of those students,” he wrote.

Completing Checkology® lessons about bias and misinformation helped Min better understand the rise in anti-Asian crimes that has occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. “These hate crimes are typically fueled by lies that people consumed whether it be a straight lie or from faulty sources,” she said. “My experience with Checkology and news literacy education has taught me about my own racial identity but has also manifested itself into my everyday life.”

She also has recognized that becoming more news-literate will serve her well not only in high school and college but also into adulthood. “By learning about news literacy education, the skills we pick up are going to be showcased throughout our lives.”

Kyrie M. Blue

Finalist, 2021 Gwen Ifill Middle School Student of the Year

Central Middle School

Quincy, Massachusetts

Kyrie M. Blue, 14, is committed to using her voice and helping others do the same in the name of social justice. And she has found that being well-informed about events and issues that shape society is key to doing so.

Kyrie M. Blue, 14, is committed to using her voice and helping others do the same in the name of social justice. And she has found that being well-informed about events and issues that shape society is key to doing so.

Librarian Helen Mastico, who nominated Blue for the student award, said she has matured from a shy student to a classroom leader. “Kyrie Blue is an impassioned student who is actively involved in fighting for social justice. Since attending our school debate club in grade six, she has overcome her shyness to become an active participant,” Mastico wrote to NLP.

Blue’s mastery of news literacy is evident in the comprehensive and visually appealing infographic she submitted to NLP. Titled “What I learned from Checkology®,” the work features images and icons that function as signposts and entry points for the reader to digest detailed explanations of key news literacy concepts. She includes First Amendment rights, freedom of speech, the limits to constitutional amendments, “fake news” and the effects of the digital world on how we consume news.

“Checkology is a great tool. It taught me to be open-minded and appreciative of all the rights I have in America, but it has also taught me to be cautious and find out the truth for myself,” Blue wrote in her summary.

She noted “how the freedoms of the First Amendment are little sets of independent rights each American has. Rights that protect us from tyranny and allow us to live independently of the government.” Blue demonstrated an understanding of how a lack of accountability gives people and organizations free rein to post whatever they want online and highlight different logical fallacies.

Mastico noted that recognition from NLP would help Blue grow even more. “The Gwen Ifill Award will help her find her voice and be a louder advocate for herself and the people around her.”

And that is exactly what Blue said she hopes to do. ”I want to teach others what Checkology taught me. It made me want to learn more about my rights and freedoms, and it made me want to find out what I want to do in the future to help others.”

Related Stories:

- NLP honors 2021 News Literacy Change-Makers

- NLP’s Journalist of the Year has witnessed harm misinformation can inflict

- Educator helps integrate news literacy across disciplines

- News literacy skills help student better understand hard of bias, misinformation

- Student gains knowledge, confidence to help stop misinformation’s spread

NLP Joins Call to Support Local News

Today, the News Literacy Project (NLP) joined more than 3,000 diverse, locally owned, nonprofit and community-based newsrooms calling on congressional leaders to provide support for America’s community newsrooms in the infrastructure bill. Led by the Rebuild Local News coalition, the group sent a letter to Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy stating, “Local news is a pillar of democracy’s infrastructure – and it is crumbling.”

The letter noted that “news deserts and ‘ghost newspapers’ – newsrooms so desolate that they don’t truly cover the town – abound across the country, especially in rural areas and communities of color. The vacuums are being filled by social media, partisan hyperbole, and harmful disinformation.”

NLP founder and CEO Alan Miller explained that NLP joined in signing because “getting people to be more informed and engaged in their communities is at the heart of our mission and that only works if there are viable local news organizations that provide the public with fact-based, standards-based news and information.”

NLP joins 20 other signatories, including the American Journalism Project; the Association of Alternative Newsmedia; the Institute for Nonprofit News; the National Association of Hispanic Publications; the National Federation of Community Broadcasters; the National Newspaper Association; PEN America; Report for America / The GroundTruth Project; the Solutions Journalism Network, and others.

Read the full letter here.

NLPeople: John Silva, senior director of education and training

John Silva

Chicago

is is the first in an occasional series that introduces you to the people behind the scenes at the News Literacy Project.

Silva and his debate team at Lindblom Math & Science Academy in Chicago

1. Can you tell us about your background and what brought you to NLP?

Prior to joining NLP four years ago, I was a classroom teacher for 13 years. I taught middle and high school social studies in Chicago Public Schools. I was actually introduced to NLP’s early programs while teaching middle school. I taught a variety of subjects, but my favorites were “History of Chicago” and “Argument and Debate.” Before becoming a teacher, I worked in a variety of positions in corporate telecommunications (which I hated) mostly focused on cellular and wireless networking. I’ve lived in Chicago for almost 25 years but I grew up mostly in California (Navy brat).

2. You are a veteran of the U.S. Marines. Could you share a little bit of your experience serving your country?

Having grown up in a military family, I enlisted and served in the end years of the Cold War. Enlisting was almost expected (though my old man hated that I joined the Marines). My dad spent 27 years in the Navy; my sister retired from the Navy after 25 years, and our Mom was a Marine in the late ‘60s. It was at times exceptionally challenging and other times very boring. I was selected for the Marine Presidential Guard program and served with the Guard Company at the Marine Barracks in Washington, D.C. Later I transferred to the Fleet Marine Force as an infantryman assigned to the 1st Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment at Camp Pendleton, California. I did get to visit some amazing places while deployed with the 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit (Special Operations Capable) including parts of Asia, the Middle East, the Horn of Africa and Australia.

PFC John Silva, USMC, School of Infantry, Camp Pendleton, California, 1990.

3. How has being a Marine influenced your work or your approach to life?

Part of why I hated corporate America was that it didn’t feel like there was a real purpose. I was just another worker in a sea of cubicles, and none of us really cared about why we were doing our jobs. It was because of that experience that I quit my job and enrolled in school to earn my teaching degree at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Becoming a teacher was in many ways similar to serving in the military. I was part of a team of professionals working towards a larger, important goal. Each of us had to contribute to the success of our mission. I have that same sense of purpose with our work at NLP.

4. What is the most surprising thing you have learned or experienced since joining NLP?

I think watching the explosive growth of conspiracy theories like QAnon has been fascinating and disconcerting to watch. The pandemic in particular created a perfect storm for those beliefs to flourish (much like a virus). I’ve also been surprised by how much my son Alex, 11, has learned from being around my work and how much misinformation he’s already being exposed to. He’s really interested in conspiracy theories and knows way more about them than any 11-year-old should. I guess that would be the most surprising – my son and I have bonded over conspiracy theories.

5. What news literacy tip, tool or guidance do you most often use or recommend?

When in doubt, Google it. So much false information can be easily debunked in less than 20 seconds.

6. What is the first thing you will do once we fully emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic?

I am really looking forward to traveling again. I travel a lot for work, which is fun, but I also try to travel a few times a year for pleasure. My girlfriend and I already have several ideas in mind for trips, and I have promised my son a trip to see the Grand Canyon.

John and his son, Alex.

7. Aside from fighting for facts, what else are you passionate about?

I love to cook. A couple of years ago I took a week off from work to go to a five-day culinary “boot camp” at The Chopping Block here in Chicago. I learned so much, and it’s a joy to prepare good food for people. I plan to enroll in the follow-up course at some point to learn some advanced skills. I’m also hoping to start teaching my son soon. He’s becoming a real foodie and loves trying new foods. Also, I bought a house about six months ago and I have been enjoying decorating and updating it. I recently started working to create space for a small garden.

John’s cat, Minuette, on the shelf John built for her to look out the window.

8. Are you on team dog, team cat, team wombat?

I am team cat. I adopted Minuette two years ago. She has a special perch for the window in my office and makes frequent appearances in my video calls and webinars. I’ve also become good friends with Hazel and Petunia, my girlfriend’s basset hounds.

9. What one item do you always have in your refrigerator?

I always have frozen minced garlic for cooking and real maple syrup for making an Old Fashioned.

10. What’s in your messenger bag right now?

I have a small leather notebook holder (I’m old school and prefer to write things down), a big water bottle and my Kindle. Those three things are always in my bag.

Teachers share how they used Checkology in challenging year

The 2020-21 school year has been anything but routine for teachers and students all over the world. Unpredictability led to a mixture of remote, hybrid and in-person learning environments — with some classrooms experiencing all three. At the same time, demand grew for resources to teach students how to separate fact from fiction and identify and combat dangerous misinformation. The Checkology® virtual classroom was an ideal resource to meet that demand across learning environments.

The News Literacy Project (NLP) set out to better understand educators’ experiences teaching news literacy. We asked several teachers to record short videos answering the question, “How did you use Checkology this past year?” Check out their responses below.

K.C. Boyd, library media specialist

Jefferson Middle School Academy, Washington, D.C.

Boyd used The Sift®, NLP’s free weekly newsletter for educators, to “jump start” her news literacy lessons. When the jury delivered its verdict convicting former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin in the death of George Floyd, Boyd discussed the five core values of journalism with students in her “Media Studies” class. “I knew that day that my students were going to be inundated with a tremendous amount of information and, unfortunately, misinformation. So, I was looking for a lot of material that would help remind them to seek out credible sources,” she says. “This platform has been a tremendous support and help in my instructional program.”

Her lesson, inspired by The Sift, focused on preparing students to actively seek out credible information concerning the trial and verdict.

Referenced lessons and resources to check out:

These two issues of The Sift are most relevant to Boyd’s lesson planning regarding the Chauvin trial:

- The Sift: Media trust insights | Covering Minneapolis | Spotting fake science – This issue discusses the five core values of journalism: “acting as watchdogs over powerful people; making information open and transparent; valuing facts in pursuit of truth; offering a voice to those lacking power; and shining light on societal problems.”

- The Sift: ’60 Minutes’ controversy | Trial coverage choices | Biden press questions – This issue includes classroom-ready slides about how local, national and international news organizations handled Chauvin trial testimony.

Maia Hawthorne, AP English and speech instructor

Twin Lakes High School, Monticello, Indiana

Hawthorne presented a four-day intensive news literacy mini-unit that featured lessons from Checkology, followed by news literacy “moments” throughout the year. She began by having students take the “How news-literate are you?” quiz. The results were “eye-opening” for her students, she says. They “are shocked to find out how little they actually know about how news works.” Afterward, “[students] consistently tell me that they love Checkology because it’s a chance to practice what they’ve been hearing, it’s hands on, it resembles things that they see when they go online and also it gives them a break from listening to me so much.” She taught mostly in-person during the 2020-21 school year.

Referenced lessons and resources to check out:

- Checkology virtual classroom – Checkology, NLP’s free e-learning platform, helps give students the habits of mind and tools to evaluate and interpret information.

- News Lit Quiz: “How news-literate are you?”

- Pear Deck – Hawthorne used Pear Deck to get feedback from students while presenting information about news literacy.

- The Sift – NLP’s free weekly newsletter for educators — delivered during the school year — explores timely examples of misinformation, addresses media and press freedom topics and discusses social media trends and issues.

- Check Center Missions – Hawthorne’s students “especially love[d] the Check Center missions where they feel like detectives.” Missions are fact-checking activities in which students get to the bottom of a piece of information using digital verification tools and skills they learn about in the Check Center.

Patricia Russac, library director and history teacher

Buckley Country Day School, Roslyn, New York

Russac taught in a hybrid learning environment this year and says the act of “teaching out and teaching in” was not easy. She used Checkology with sixth- and seventh-graders to build their news literacy skills and noted that Checkology worked well “because the resources are so accessible to remote learners as well as to students in the room.” After each lesson segment, Russac gave students the opportunity to ask questions and participate in class discussions. “The students had plenty to share about what they heard, saw and viewed online,” she says. “It was a powerful reminder as to why news literacy education should be part of every grade level and across subjects. It is not enough to teach it just in the humanities. Math and science need news literacy education as well. Data matters.”

Referenced lessons and resources to check out:

Russac’s students completed four Checkology lessons to develop their news literacy skills. Of the four, the students’ favorite lesson was “Conspiratorial Thinking.” Use the demo links below to preview the lessons. To learn how to assign lessons to students, check out our “Quick guide to assigning a course.” Here are the Checkology lessons Russac taught:

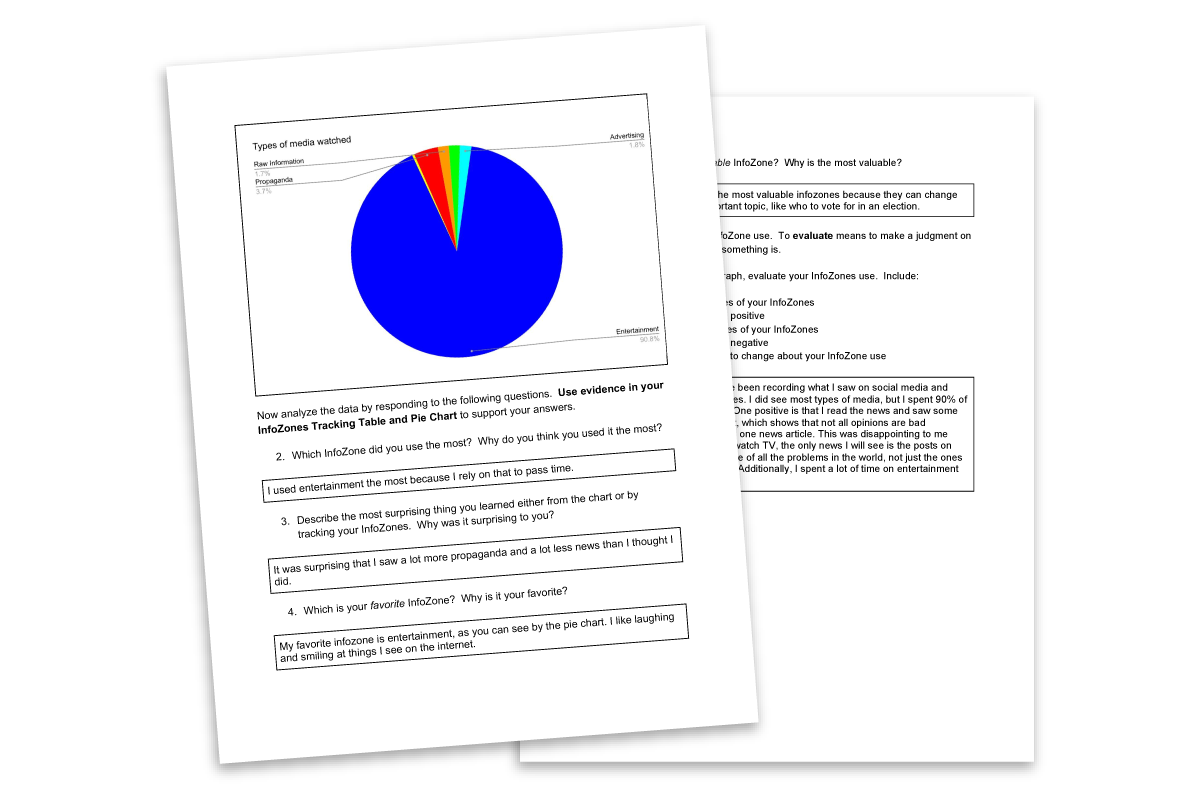

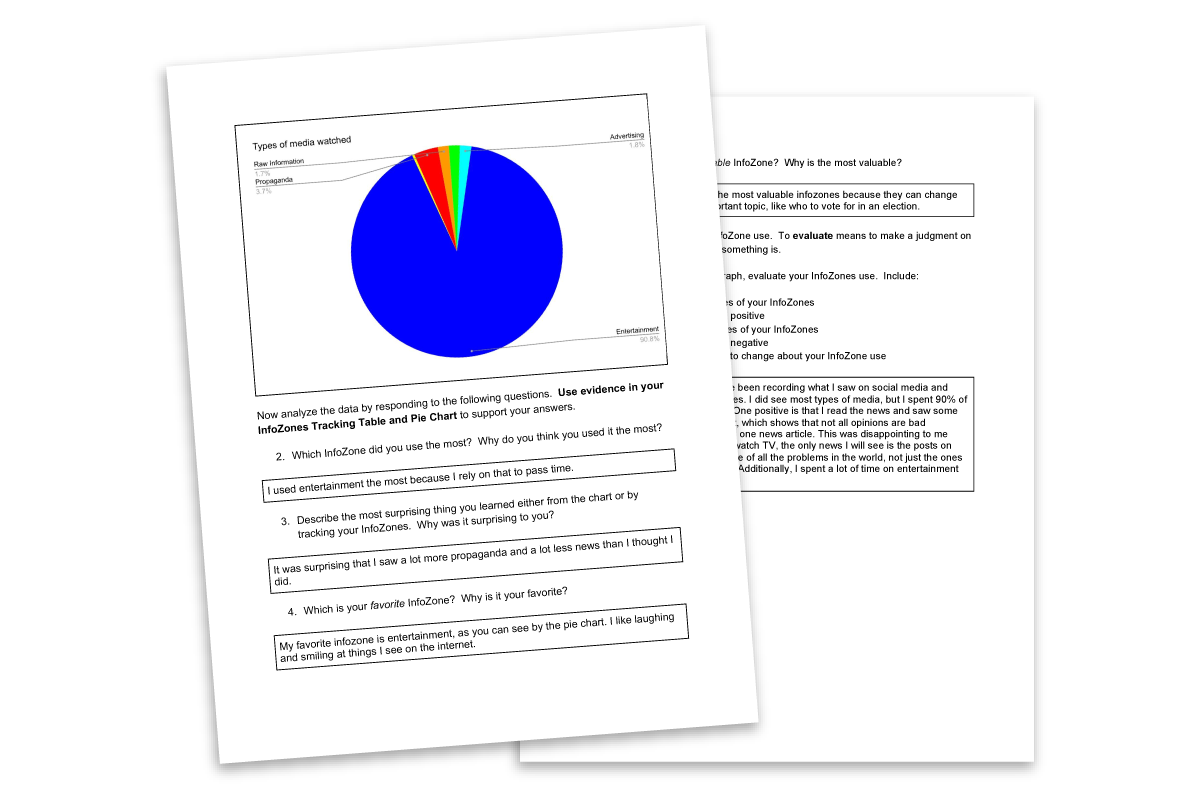

- “InfoZones”– Categorize information into one of six “zones:” news, opinion, entertainment, advertising, propaganda or raw information.

- “Misinformation” – Learn to understand different types of misinformation and the ways that it can damage democracy.

- “Understanding Bias” – Develop a nuanced understanding of news media bias by learning about five types of bias and five ways it can manifest itself, as well as methods for minimizing it.

- “Conspiratorial Thinking” – Discover why people are drawn to conspiracy theories and how our cognitive biases can trick us into believing they’re real.

Lauren Walton, library media specialist

North Reading Middle School, North Reading, Massachusetts

Walton created a brand-new digital literacy curriculum and used Checkology in a hybrid learning environment. “The interactive format of Checkology and my ability to see each individual student’s answers and progress kept students engaged and helped me assess students’ understanding and mastery of skills,” she says. Her middle school students particularly enjoyed the lesson “Arguments and Evidence,” because of their passion for debate. Using Checkology to support her digital literacy curriculum, Walton was able to help students “go from blindly accepting everything they read online to critically examining each piece of information to determine its author, purpose, and credibility.”

Referenced lessons and resources to check out:

You can find and assign Walton’s digital literacy course to your own class. Just select “Change course” in the course management area and assign “Digital literacy (by educator Lauren Walton)” under the preset course options that appear. Here are the core lessons featured in her course:

- “Introduction to Algorithms”

- “InfoZones”

- “Arguments & Evidence”

- “Understanding Bias”

Walton’s course also featured exercises, challenges and Check Center missions to help reinforce and extend student learning, which she found valuable. “I recommend that educators who are thinking about implementing Checkology into their classrooms use the Check Center…and show students the videos on fact-checking skills.”

Diana Montague, professor of communication and department chair

University of Findlay, Findlay, Ohio

Montague noticed that “students, like many adults, really struggle to distinguish news from opinions.” That’s why, in her “Principles of Speech” course, she asked students to choose a current event or issue and find a news article and an opinion piece relating to it. Her students then fact-checked and sourced both pieces of information. “Checkology was an excellent tool to introduce our speech students to some of the categories of mediated information and give them a vocabulary to identify and distinguish news from opinion, news from propaganda or advertisements, and curated, verified news from raw information,” Montague says. “Checkology also helped [students] look for red flags to identify misinformation and it gave students some insight into how conspiracy theories are started and disseminated in the media.”

Her university experienced a variety of learning environments (in-person, fully remote and hybrid), and she credited “the asynchronous platform of Checkology” as providing “a stable set of exercises no matter where students were at any given time.” She enhanced her students’ learning by connecting lessons to what was unfolding in the news. “If you are planning on using Checkology, I would encourage you to reinforce the lessons by pulling in the day’s news, opinions or trending topics on social media feeds. This encourages students to apply what they learned from the exercises to breaking news,” she says.

Referenced lessons and resources to check out:

Montague assigned three core Checkology lessons to develop students’ news and media literacy. Use the demo links below to preview the lessons. To learn how to assign lessons to students, check out our “Quick guide to assigning a course.”

- “InfoZones” – Categorize information into one of six “zones”: news, opinion, entertainment, advertising, propaganda or raw information.

- “Misinformation” – Learn to understand different types of misinformation and the ways that misinformation can damage democracy.

- “Conspiratorial Thinking” – Discover why people are drawn to conspiracy theories and how our cognitive biases can trick us into believing they’re real.

Liz Norell, political science professor

Chattanooga State Community College, Chattanooga, Tennessee

This spring, Norell taught fully remote classes, and offered students course credit to complete some or all Checkology assignments and write a short reflection on what they learned. She knew that Checkology content would align well with her course focus “on how to become a competent citizen, how to evaluate information and how to have civil conversations across political differences.” It became clear to Norell after reading student reflections that “they thought they would be really good at determining what information was trustworthy or not and they really learned a lot.” Based on her experience, she encourages other educators to use the platform. “I hope that others will jump on board because I think [Checkology is] exactly what our students need at this moment in our history and in this political sphere,” she says.

Referenced lessons and resources to check out:

To replicate Norell’s student-choice-driven use of Checkology, simply assign the “All lessons” preset course to your class and then turn off the “Course Lock” setting. This will allow your students to see all available Checkology lessons and begin them in any order.

Vaccines and Misinformation | How to interpret data on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines

This article is part of a series presented by our partner SAS that explores the role of data in understanding COVID-19. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

If there’s one thing people want to know most about a vaccine, it’s this: Does it work?

So naturally, as COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials were being completed and vaccines were being considered for emergency use authorization, the numbers that featured most heavily in the news were efficacy rates.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine boasted an efficacy rating of 95%, Moderna 94% and Johnson & Johnson 72%. But what do those numbers really mean? How can individuals use these numbers to make decisions for their families?

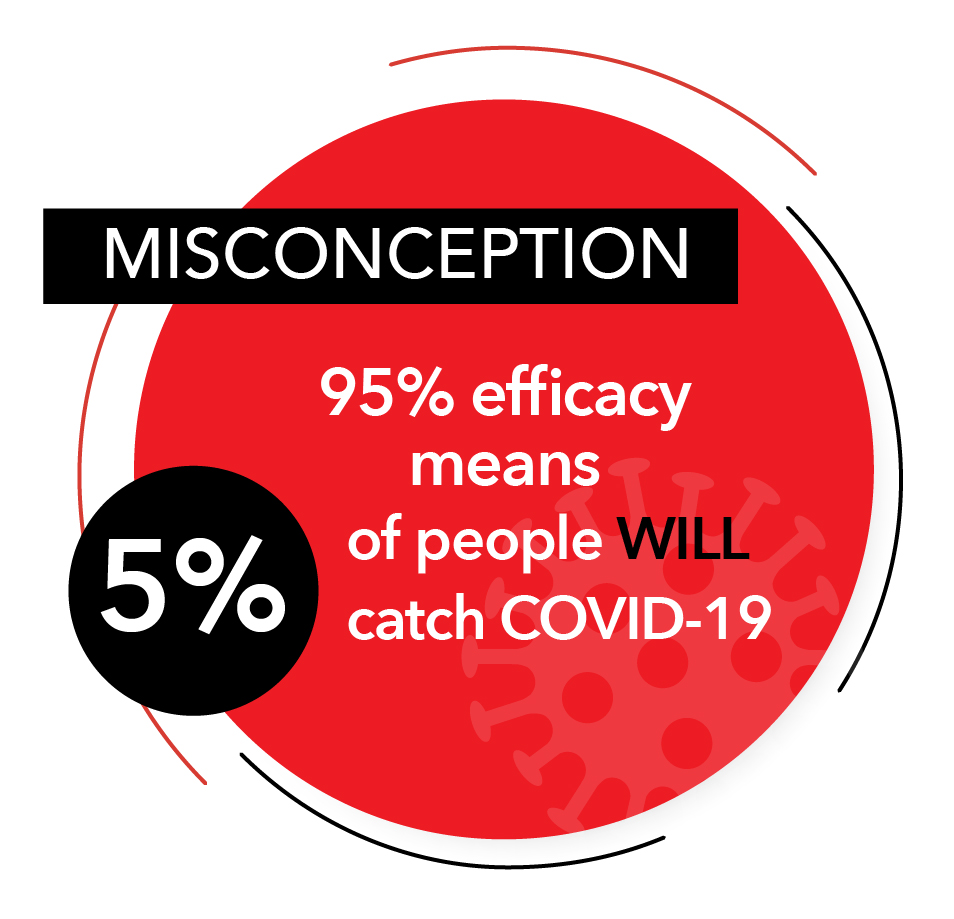

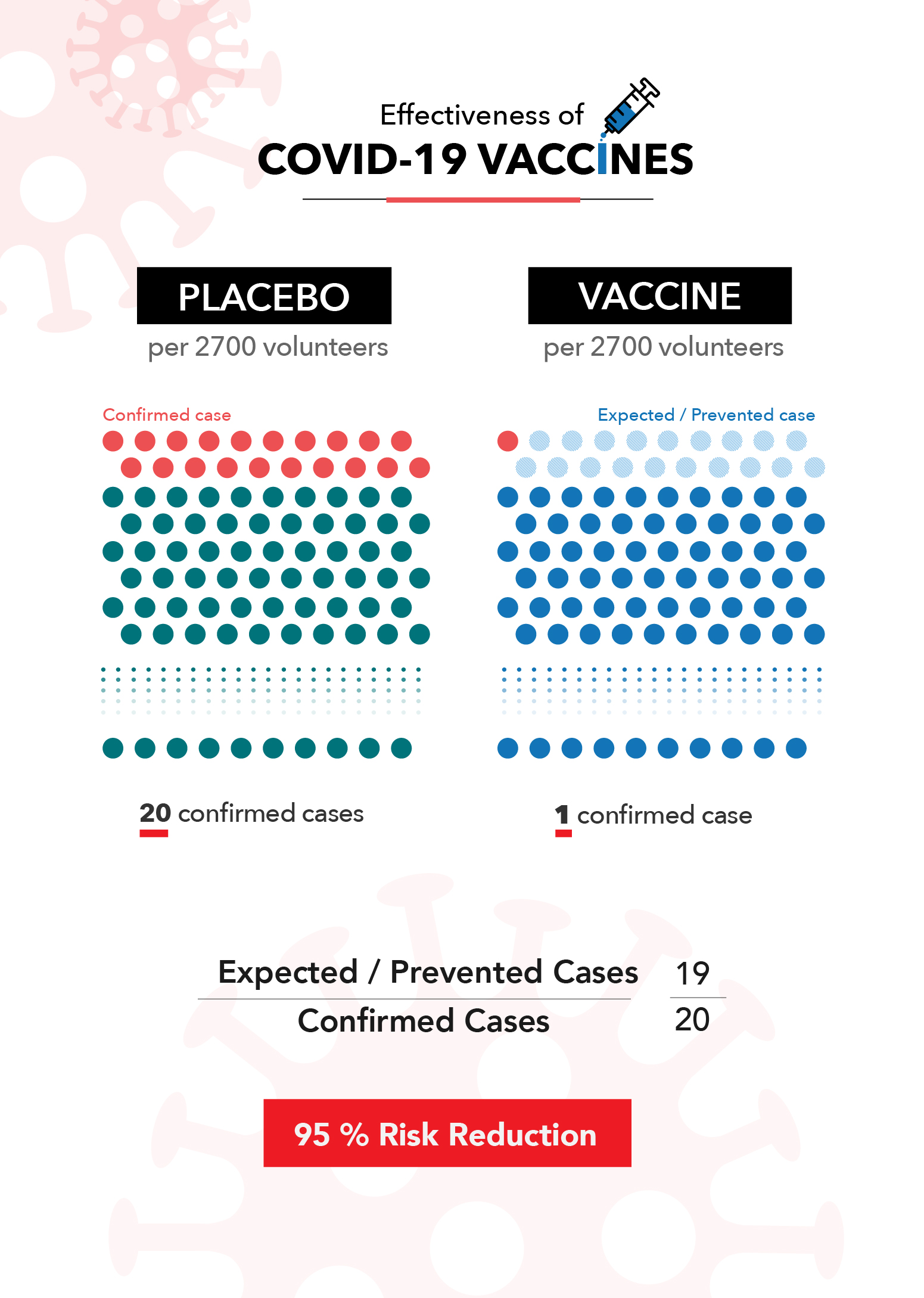

One common misconception is that a 95% efficacy rate means that 5% of the participants in the trial contracted COVID-19, and that similarly, 5% of the vaccinated population will catch it as well. That is not the case. The purpose of the efficacy rating is to show how much the RISK of catching the disease is reduced.

One common misconception is that a 95% efficacy rate means that 5% of the participants in the trial contracted COVID-19, and that similarly, 5% of the vaccinated population will catch it as well. That is not the case. The purpose of the efficacy rating is to show how much the RISK of catching the disease is reduced.

Let’s look at what this means using the Pfizer-BioNTech clinical trial. According to their released data, 160 out of the 21,728 people in the placebo group tested positive for COVID-19. Conversely, more than a week after receiving the second vaccine dose, only eight out of 21,720 people tested positive.

This means that over the course of the trial, it could be expected that the average unvaccinated person had a 0.7% chance of catching COVID-19. Alternatively, if you had received the Pfizer vaccine, you had a 0.04% chance of catching it. This is where their 95% efficacy rating comes from. It means that there were 95% fewer cases than would have been expected if the trial participants were not vaccinated.

Clinical trials can be hard to compare to one another because they occur during different time periods, in different places and have different definitions and criteria. This is a major reason health officials caution against comparing the efficacy numbers of different vaccines against one another. Small variances in the details of the trial can impact the final numbers.

The unique nature of clinical trials can also lead people to wonder how the vaccines perform in the real world, especially when issues like new variants come into play. Thankfully, we’re already seeing evidence that the real-world effectiveness of these vaccines matches up with the numbers reported in their clinical trials.

Now that a significant portion of the population is fully vaccinated, we can also examine recent, in-the-wild data to further understand how the vaccines reduce risk. We know that the vaccines aren’t perfect, and the CDC is actively collecting data on breakthrough cases (confirmed infections among vaccinated people).

As of April 26, the CDC reported 9,245 infections among the more than 95 million Americans who had been fully vaccinated. Using historical data* as a benchmark, an average of 264 vaccinated Americans tested positive for COVID-19 per day over the last two weeks of April. During that same period, the U.S. saw an average of 62,800 new cases per day among the entire population. That roughly equates to three cases per 1 million vaccinated Americans per day, compared to about 260 cases per 1 million unvaccinated Americans per day. It’s not perfect, but it represents a significant reduction in risk.

During that same two-week period, the U.S. recorded 8,926 total deaths due to COVID-19, 58 of which were fully vaccinated individuals. Given what we know about the size of the vaccinated and unvaccinated population, this means that vaccines likely saved at least 3,000 lives in those two weeks alone. The total lives saved is likely even higher, when one accounts for the fact that the demographics of the first groups of vaccinated Americans were among the most vulnerable for severe complications and death due to COVID-19.So what does all of this mean as you consider whether the vaccine is a good choice for you and your family? Getting the vaccine does not offer a guarantee that you won’t catch the disease or get seriously ill from it. But it does offer a very significant reduction of risk.

For example, consider that wearing seatbelts in a car is estimated to carry a 45% reduction in risk of death, and doing so is a choice most of us would make whether it was the law or not. Even if we believe our risk of an auto accident is low, we still make a conscious choice to further reduce the possibility of severe injury. Seatbelts don’t offer 100% protection, and neither do COVID-19 vaccines, but the data shows the added safety is worth it.

* As of May 14 the CDC has changed how they report breakthrough cases. Visit the CDC website for up-to-date information.

About SAS: Through innovative analytics software and services, SAS helps customers around the world transform data into intelligence.

About SAS: Through innovative analytics software and services, SAS helps customers around the world transform data into intelligence.

Vaccines and Misinformation | Understanding how misinformation can fuel vaccine hesitancy

Misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine is contributing to a hesitancy to get vaccinated. In an effort to separate fact from fiction and provide a better understanding of the reasons for that reluctance, we’re going to spend this week focusing on the issue and providing trustworthy information about it.

NLP’s staff members snapped selfies while getting their vaccine shot.

We’re starting with an update to our COVID-19 webpage, which includes links to credible health care organizations and reporting that have debunked many of the myths surrounding the vaccines. Additional resources dive more directly into the reasons people have expressed for not getting a shot. Our friends at SAS are providing context to the data about the vaccines that we hope will show you how effective they’ve been in preventing the spread and harm from the virus.

We’re also producing a special episode of our podcast Is that a fact? We’ll get insight from Dr. Erica Pan, California state epidemiologist and deputy director for the Center for Infectious Diseases at the California Department of Public Health, and Brandy Zadrozny, a senior reporter for NBC News who covers misinformation, extremism and the internet. They share their expertise on how the vaccines were created, their effectiveness, the impact of misinformation on vaccine hesitancy and how anti-vaxxers have used the pandemic to sow more confusion and grow their ranks.

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced new guidelines stating that “fully vaccinated people no longer need to wear a mask or physically distance in any setting,” along with some specific exceptions. It’s clear that the vaccinations are saving lives, reducing the health risks of the virus and helping us return to some semblance of normalcy. We hope that by providing this information, you can help the people in your community make informed decisions about getting the vaccines. Please share these resources, and remember, the best advice we can offer people who are hesitant to get a vaccine is to suggest that they talk to their health care provider about the benefits and risks of getting vaccinated.

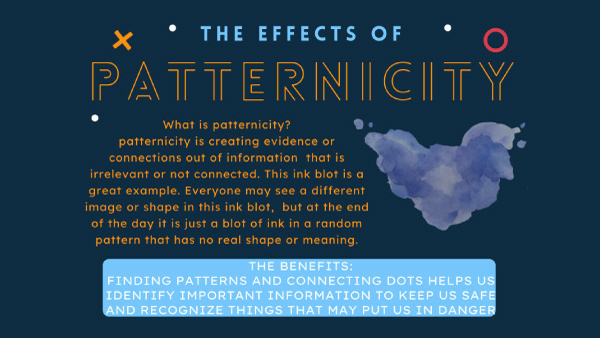

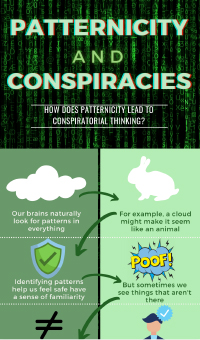

Patternicity contest demonstrates mastery of key concept

Our brains are built to look for patterns, and we tend to see them everywhere. We look up at a cloud and see the shape of a cat. Or we recognize the outline of a face in a puddle.

Patternicity is the term for this tendency to perceive meaningful patterns and connections among unrelated events. It’s often a harmless diversion. However, it can be used to support a belief that is otherwise lacking in evidence, like a conspiracy theory.

NLP created a contest to measure Checkology® students’ understanding of patternicity — an important news literacy concept. Students submitted a poster or infographic explaining the dangers of creating or believing false evidence rooted in patternicity.

Grace Bradley of Missouri won NLP’s first patternicity contest. The senior is a student in Nicole Cusick’s English class at Lee’s Summit West High School. Cusick taught patternicity in her media studies course as part of a segment on conspiratorial thinking. The course asks students to seriously evaluate media consumption and media’s role in society.

“When I saw the contest, I originally thought it would be a fun way to learn about conspiracy theories. After a closer look, I thought it would be a perfect way to have an authentic assessment of their learning about how conspiratorial thinking develops and the impact it can have on us and our society,” Cusick says.

Clear definition of patternicity

Kim Bowman, NLP’s user success associate, says Grace’s entry offered a clear definition of what patternicity is and why we tend to look for patterns. “Grace skillfully explained the dangers of this illusory perception (when it leads to conspiratorial thinking) using topical examples. In addition to being very informative, the final product was creative and unique with both the layout and images.”

“It was such a fun assignment and project, and I’m so proud of my infographic, so I’m really happy I won,” Grace says.

She also enjoyed using Checkology to study news literacy. For example, she likes the ease of use, ability to learn at her own pace and relevancy of the lessons. “I like how much effort they have put in to making it more interesting and interactive as well. They’re really moving with the times. Everything is tailored to high school students, and it really shows,” says Grace.

And the contest itself motivated students, Cusick says. The recognition helped them see the payoff from their hard work. It also gave students a new perspective about what they learn and why. “They are seeing how the skills of my English classroom are applicable to their lives outside of the classroom as well,” she says.

Click image thumbnails above to view the full posters created by Gabby Reynolds, Noah Stice and Miyabi Schroth (left to right).

The patternicity contest runners-up included two of Grace’s classmates: Gabby Reynolds and Noah Stice. Miyabi Schroth of Berkeley, California, is the other runner-up. Schroth is a student in teacher-librarian Melanie Ford’s class at Longfellow Arts and Technology Middle School, where the eighth-grader is also a library assistant.

Grace and Cusick will receive an assortment of NLP-branded swag in recognition of their work.

Celebrating AAPI journalists and news media

More than 40 years ago, the United States first celebrated the heritage of Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) with a commemorative week in May 1979. But this year, amid disturbing violence and abuse targeted at Asian-Americans, immigrants and other people of color, appreciating the culture and contributions of the AAPI community is more important than ever.

Photo credit: Franz Lopez on Flickr, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

For Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month, NLP is highlighting AAPI journalists and news organizations — past and present — on social media. We begin with Rappler co-founder and CEO Maria Ressa. She received the 2021 UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize on the eve of World Press Freedom Day, May 3. Ressa, a Filipina-American journalist, and her team continue their unflinching coverage of President Rodrigo Duterte’s authoritarian rule in the Philippines despite harassment, threats and jail time. In 2020, Ressa was a guest on NLP’s podcast Is that a fact?, where she discussed her work and why she presses on despite the risks. “… you don’t wake up and you say, ‘I’m going to fight for press freedom.’ I never did. I just did my job,” she told us.

Important AAPI milestones

So why is May Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month? The U.S. Congress selected this time of year to celebrate the AAPI community because of important milestones. “The month of May was chosen to commemorate the immigration of the first Japanese to the United States on May 7, 1843, and to mark the anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869. The majority of the workers who laid the tracks were Chinese immigrants,” according to the Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month website. Educators will find lessons plans and other classroom-ready resources for teaching about AAPI heritage on the site.

And be sure to follow our thread on Twitter throughout the month as we focus on the impact of AAPI journalists and news organizations @NewsLitProject.

Behind the headlines: Blocking press freedoms

This article is from a previous issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

By Suzannah Gonzales

Journalism — “arguably the best vaccine against the virus of disinformation” — is obstructed in a majority of countries around the world, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and its new press freedom ranking.

The 2021 World Press Freedom Index, an annual ranking of 180 countries and territories, showed that journalism “is totally blocked or seriously impeded in … 73% of the countries evaluated.” The “data reflect a dramatic deterioration in people’s access to information and an increase in obstacles to news coverage,” an overview of the ranking said. COVID-19 is being used to block availability to sources and reporting on the ground, making it hard to cover controversial stories. RSF questioned whether access will improve once the pandemic ends.

In addition, RSF noted a troubling measure of public mistrust of journalists, citing the results of a survey in 28 countries called the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer. It found that nearly 60% of those who responded believe “journalists deliberately try to mislead the public by reporting information they know to be false” when in actuality, journalism combats “infodemics” of misinformation and disinformation, RSF said.

The United States advanced one place (to 44) with its press freedom categorized as “fairly good,” RSF said, despite unprecedented numbers of assaults against and arrests of journalists (about 400 and 130, respectively).

Norway remained at the top of the list for the fifth year, and Finland held on to its second-place spot while Sweden reclaimed its third-place ranking. Totalitarian countries once again claimed the bottom three places — Turkmenistan (178), North Korea (179) and Eritrea (180). Malaysia, which recently enacted a law against what authorities deem false content, dropped the most in the ranking — 18 spots to 119.

Related:

- “Governments are using Covid-19 as an excuse to crack down on press freedom” (Sara Torsner and Jackie Harrison, Nieman Lab).

- “Guilty Verdict for Hong Kong Journalist as Media Faces ‘Frontal Assault’” (Austin Ramzy and Tiffany May, The New York Times).

- “Very telling/chilling response by Hong Kong government to latest RSF press freedom rankings” (Timothy McLaughlin, Twitter).

- “Listening to what trust in news means to users: qualitative evidence from four countries” (Reuters Institute).

Behind the headlines: Values, trust and media

This article is from a previous issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

By Hannah Covington

It can be tempting to view the public’s distrust of the news media as simply a matter of political differences. But a recent study offers new ways of looking at and addressing the “media trust crisis.” It suggests that not all Americans embrace the core values that journalists follow in their work, and that this misalignment — rather than partisanship — may help better explain media trust divides. For example, people who value authority and loyalty may be wary of journalists’ role as watchdogs over the powerful.

“When journalists say they are just doing their jobs, in other words, the problem is many people harbor doubts about what the job should be,” the report said.

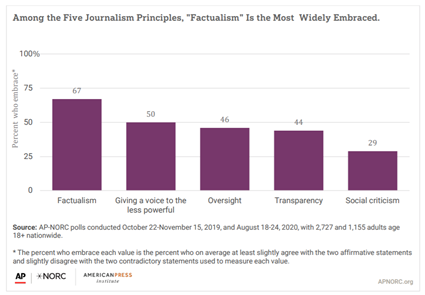

The study was released on April 14 by the Media Insight Project — a collaboration of the American Press Institute and The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research — and examined “public attitudes toward five core values of journalistic inquiry.”

Most agree on importance of facts

These values include acting as watchdogs over powerful people; making information open and transparent; valuing facts in pursuit of truth; offering a voice to those lacking power; and shining light on societal problems.

Only 11% of Americans fully embrace all five of these principles, the study found. The importance of facts in pursuit of truth attracted the most widespread support (67%), while just 29% of Americans embraced spotlighting social problems as an effective way to solve them. Distrust among these groups, the study points out, “goes beyond traditional partisan politics.”

The study highlights ways that news organizations can rebuild trust without compromising core values. Simple tweaks to headlines, first sentences and story framing, for instance, can go a long way to broaden the appeal of news reports among a wider audience.

Related:

- “American Views 2020: Trust, Media and Democracy” (Gallup and Knight Foundation).

- “Americans See Skepticism of News Media as Healthy, Say Public Trust in the Institution Can Improve” (Pew Research Center).

Behind the headlines: Clarity or deception?

This article is from a previous issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

Written by: Peter Adams

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis answers questions about his state’s COVID-19 response at a press conference at the Urban League of Broward County on April 17, 2020.

An April 4 report from the long-running CBS News newsmagazine 60 Minutes on disparities in Florida’s vaccine rollout has touched off a wave of criticism questioning the piece’s accuracy and fairness.

The controversy stems from the report’s unsupported suggestion that Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis used the state’s vaccination program to engage in a “pay-to-play” scheme with the supermarket chain Publix when he announced a distribution partnership with the company in January, shortly after it donated $100,000 to his political action committee.

But critics of this segment of the report say it failed to provide substantive evidence of wrongdoing and mischaracterized key details. The report also included footage from a press briefing at which 60 Minutes correspondent Sharyn Alfonsi asked DeSantis about the Publix relationship. However, important parts showing DeSantis denying wrongdoing (at 32:30 in footage of the briefing) weren’t included in the clip. The director of the Florida Division of Emergency Management, Jared Moskowitz, and Palm Beach County Mayor Dave Kerner, who are both Democrats, have backed up the governor’s account.

CBS News defended the edits and stands by the report. At the conclusion of its April 11 episode, 60 Minutes acknowledged criticism of its report and read several letters from viewers. DeSantis, meanwhile, has responded to the incident by going on the offensive, broadly accusing “partisan corporate media” of maliciously trying to damage him.

Note: Most of the 60 Minutes report presented accurate information about well-documented racial and economic disparities in the state’s COVID-19 vaccination distribution. But the controversy over the DeSantis allegations overshadowed that reporting.

Also note: CBS said DeSantis declined to be interviewed by 60 Minutes for the report.

Related:

- “Opinion: ‘60 Minutes’ embraces innuendo in Ron DeSantis story” (Erik Wemple, The Washington Post).

- “Not everything was wrong with the ‘60 Minutes’ story on Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and COVID-19 vaccines” (Tom Jones, Poynter).

- “Ron DeSantis is Taking His 60 Minutes Feud All the Way to the Bank” (Charlotte Klein, Vanity Fair).

- “Why Being ‘Anti-Media’ Is Now Part Of The GOP Identity” (Meredith Conroy, FiveThirtyEight).

Discuss: Can journalists include everything a source says in their reporting? How should journalists decide what portions of interviews to include and which to leave out?

Idea: Use this video comparison from NLP to highlight for students the edits 60 Minutes made to the governor’s response to Alfonsi’s question. Do they agree with CBS’ claim that these were justifiable edits made for clarity? Or do they agree with claims by DeSantis that the editing was deceptive and unfair?

Journalist’s classroom visit high point of the year for California sixth-graders

NPR journalist Hannah Bloch is used to asking questions, but during a virtual visit with 80 sixth-graders at Chaparral Middle School in Diamond Bar, California, she was the one peppered with them.

The conversation with Bloch, lead digital editor on NPR’s international desk, was the highlight of a media literacy component that educator Sherry Robertson developed for her language arts class.

“Speaking with Sherry Robertson’s class was a delight. The students were so engaged (even over Zoom, which I expected might be tough). Their questions were thoughtful, and I loved their genuine curiosity about journalism and what it’s like being a journalist,” Bloch says.

Robertson arranged the January visit through the News Literacy Project’s Newsroom to Classroom program. Part of the Checkology® e-learning platform, the program enables educators to invite vetted journalist volunteers to visit their classrooms in person or remotely.

“I felt very passionate about creating a unit on this. The younger we start, the better,” Robertson says. “I’m on a mission to do my part in the world to make my kids literate online.”

Before the visit, Robertson’s students completed the Checkology lessons “InfoZones” and “Arguments & Evidence.” They then submitted questions to Bloch ahead of time through the platform, Padlet.

Inspiring visit

Introducing a new subject area has both challenged and inspired Robertson. “As educators, we weren’t trained to teach this,” she says. “This is new for me. I’m teaching them something I’m learning at the same time.”

Bringing in a subject matter expert was a real help. The conversation with Bloch covered several topics, from what inspired her to become a journalist, to how she determines whether a story is credible, to which fast food restaurant she recommends.

“It was so amazing. She was fantastic and went out of her way to answer my kids’ questions,” Robertson says. And the conversation with a working journalist was eye-opening for her students. “She’s so accomplished, and here she is talking to them as equals. This was something my kids could aspire to. Journalism could be attainable to them. I don’t think they realized it,” she adds.

In a year when distance learning has posed significant challenges to educators, parents and kids, Robertson was able to easily arrange the visit with Bloch, who lives on the East Coast. And it was a natural fit given that everyone has essentially been “living” online since the pandemic began.

Robertson also wanted to ensure her students enjoyed their first year in middle school, despite the circumstances. She sought to keep them engaged and provide something fun. Bloch’s visit was just that. “This was literally the best experience my kids had this year,” Robertson says.

For Bloch, the visit was also a delight. “It was a pleasure to have the opportunity to spend that time with them and I’m thrilled to hear that they enjoyed it, too. And I have so much respect for the work teachers like Ms. Robertson are doing at this most challenging of times,” she says.

Behind the headlines: Sexism in journalism

This article is from a previous issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

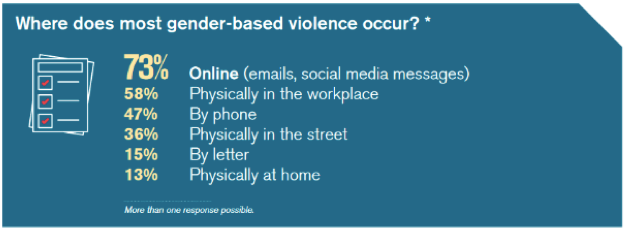

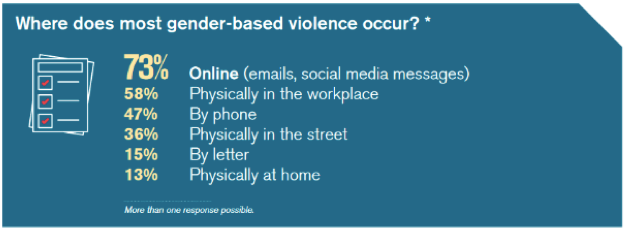

Women working as journalists increasingly face gender-based violence outside of their newsrooms, including a barrage of threats and hate online. But they also endure it inside their workplaces, from discrimination to sexual assaults and harassment, according to a new Reporters Without Borders (RSF) report detailing the toll sexism has taken on journalism.

“The two-fold danger to which many women journalists are subjected is far too common, not only in traditional reporting fields as well as new digital areas and the Internet, but also where they should be protected: in their own newsrooms,” the report said.

Reporters Without Borders “Sexism’s Toll on Journalism” report, March 8, 2021

Published on March 8 — International Women’s Day — the report includes RSF’s analysis of 112 responses to questionnaires sent to its global correspondents and journalists who cover gender, and collected between July and October 2020.

The trauma female journalists experience due to violence both in and out of the newsroom silences victims and leads some to close their social media accounts or even resign, the report found. Issues affecting women “become invisible” in news coverage when there aren’t enough women in top leadership positions, the report said: “The lack of multiple viewpoints within media organisations has major editorial consequences, including in the representation of women in the content offered to the public.”

Note: A separate March 8 report by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism revealed that 22% of top editors at 240 major news organizations are women.

Related:

- “New York Times Defends Reporter Taylor Lorenz From Tucker Carlson’s ‘Cruel’ Attack” (Jordan Moreau, Variety).

- “Carlson, Times tussle over online harassment of journalist” (David Bauder, The Associated Press).

- “Maria Ressa: Fighting an Onslaught of Online Violence” (International Center for Journalists).

- “UNESCO launches campaign to end online violence vs women journalists” (Rappler).

- “Malign Creativity: How Gender, Sex, and Lies are Weaponized Against Women Online” (Wilson Center).

Behind the headlines: Atlanta shootings coverage fallout

By Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington

This article is from this week’s issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

News coverage of the March 16 fatal shootings at Atlanta-area spas that occurred amid a recent spate of anti-Asian violence across the country spurred important debates over journalism ethics and news decisions — especially as the story first unfolded. Questions and criticisms of coverage highlighted several notable issues, including the bias and credibility of law enforcement sources; the need for more diverse news organizations, journalists and sources; and hesitation by newsrooms to call the shootings a “hate crime.”

As the story developed, the Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) published guidance for newsrooms covering the shootings. Its recommendations include providing context on the recent increasing violence, and understanding the history of anti-Asian racism. It also underscored the need to consult Asian American and Pacific Islander expert sources and to be careful with language that could contribute to “the hypersexualization of Asian women.”

AAJA reported that some newsrooms have questioned whether Asian American and Pacific Islander journalists will show bias or are “too emotionally invested” to cover the shootings. Calling such reports “deeply concerning,” it urged news organizations to empower these journalists “by recognizing both the unique value they bring to the coverage of the Atlanta shootings and the invisible labor they regularly take on, especially in newsrooms where they are severely underrepresented.”

Note: AAJA also released a pronunciation guide for Asian victims of the shootings.

Related:

- “The rush to report on Atlanta-area shootings amplified bias in news coverage” (Doris Truong, Poynter).

- “Connie Chung: The media is miserably late covering anti-Asian violence” (Alexis Benveniste, CNN Business).

- “‘Enough Is Enough’: Atlanta-Area Spa Shootings Spur Debate Over Hate Crime Label” (Bill Chappell, Dustin Jones, NPR).

- “Why don’t we know more about the Atlanta shooting victims?” (Ariana Eunjung Cha, Derek Hawkins and Meryl Kornfield, The Washington Post).

- “Teen Vogue’s New Top Editor Out After Backlash Over Old Racist Tweets” (Maxwell Tani, Lachlan Cartwright, The Daily Beast).

Statement: Base proposed voting measures on facts, not falsehoods

As numerous states consider steps to change the way voters participate in elections, we urge elected officials to base their actions on credible evidence.

We believe that the right to vote is an essential act of an informed citizenry. But legislation premised on widespread disinformation about the 2020 election — including baseless voter fraud claims and conspiracy theories — runs counter to our values and would do lasting harm to voting rights, which are among the most sacrosanct tenets of American democracy.

In a joint statement in November, two federal election security agencies assured the public that the 2020 election was ‘“the most secure in American history.” They noted: “While we know there are many unfounded claims and opportunities for misinformation about the process of our elections, we can assure you we have the utmost confidence in the security and integrity of our elections.”

NLP’s work is rooted in the belief that facts are essential to making sound decisions. That’s why we’re calling on legislators to weigh whether proposed laws represent a response to demonstrated problems with existing voting infrastructure and procedures. While we welcome changes that improve the fairness, transparency and accessibility of elections, we oppose laws based on disproven allegations and manufactured narratives that place unnecessary burdens and restrictions on Americans’ right to elect their leaders and hold them accountable.

The last election saw the largest voter turnout since 1900, and as supporters of an engaged and well-informed voting public, we will continue our work to ensure that people know how to recognize fact from fiction and to use that knowledge to exercise their democratic rights.

CNN’s Abby Phillip joins board of the News Literacy Project

“Abby brings us exceptional credentials as a journalist as well as a fresh perspective,” said Alan C. Miller, founder and CEO of NLP, the nation’s leading nonpartisan education nonprofit. “With her experience, we anticipate that she will contribute valuable insights to the board. We look forward to working with her to expand our reach and impact at this crucial moment for the country’s democracy.’’

Phillip expressed a strong commitment to NLP’s work. “The mission of the News Literacy Project has always been essential to a functioning democracy, but it is needed now more than ever,” she said. “I’m grateful for the opportunity to serve on the board of this great organization as it continues in its work of helping people navigate the modern information environment. As a journalist, I view the work of the News Literacy Project as a perfect complement to what we do every day to bring facts and the truth to the American people and our viewers and readers around the world.”

Greg McCaffery, the chair of NLP’s board, welcomed her to the organization. “Abby Phillip’s commitment to NLP’s goals and mission is clear. We are thrilled to have her join the board.”

Phillip established her initial connection to NLP in 2016 when she was a reporter at The Washington Post. She participated in a “virtual visit” event along with Matea Gold, who is now the Post’s national political enterprise and investigations editor and a member of NLP’s National Leadership Council.

Deep experience covering politics, other major stories

Based in D.C., she left the Post for CNN in 2017 to cover the Trump administration and served as White House correspondent through 2019. In January 2020, she moderated the CNN Democratic presidential debate in Iowa. She also anchored special coverage of “Election Night in America” for the 2020 election — coverage that lasted for several days until CNN was the first news outlet to project Joe Biden as the winner.

While at the Post, Phillip was a national political reporter. She covered the White House and wrote about a wide range of subjects related to the Trump administration. As a campaign reporter during the 2016 election, she covered Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign and was also a general assignment reporter, covering domestic and international news — including the mass shootings in Charleston, South Carolina, and San Bernardino, California.

Before joining the paper, Phillip was a digital reporter for politics at ABC News. She also covered the Obama White House for POLITICO as well as campaign finance and lobbying.

A graduate of Harvard University, Phillip is working on her first book, THE DREAM DEFERRED: Jesse Jackson, Black Political Power, and the Year that Changed America, which will be released in 2022. It will be the first major contemporary book on the life and political legacy of Jackson, focusing on his groundbreaking run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1988.

News literacy ambassador brings ‘seasoned’ approach to education

An award-winning history teacher at the Gordon Parks School for Inquisitive Minds in Queens, New York, and a news literacy ambassador for NLP, Street is committed to elevating her students’ learning experience through her “seasoned” approach.

“I remember many years ago, I bought a wok and was washing it out. My brother said, ‘Don’t wash it with soap and water, just wipe it out so that every time you cook, it seasons the food,’” she recalls. “When you add a little heat to something, you bring a whole lot of different flavors.”

This cooking metaphor, she believes, applies to teaching.

Street, who became an educator after working on Wall Street, harvests the flavors from a diversity of experiences and opportunities that she brings to the classroom. Here are just a few examples. She is a member of the New York State Council for the Social Studies Supervisory Committee and completed New York City’s Leaders in Education Apprentice Program. She studied the African diaspora at New York University and attended the Tufts in London program. Also, she earned a certificate in education leadership and administration from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education.

News literacy ambassador, teacher

This ever-curious and engaged approach to learning and life led her to make news literacy education an imperative. “I have been teaching it because I’m compelled to do so. Because we’re living it,” says Street. This year, because of COVID-19 restrictions, she teaches history remotely to 74 eighth-graders.

NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom is a main ingredient in this instruction. “When I went into Checkology, I just wanted to stay in there all day,” Street says. She considers the guidance to stop and weigh information before believing, sharing or taking action a fundamental lesson. “I use that in the classroom. I’ll say, ‘Let’s pause. Before you make a decision, make sure you are well informed.’”

Relying on events both current and historical, she encourages students to make their own realizations about the information they encounter. She reminds them, “I’m not here to tell you what to think; it’s my goal to get you to think.”

A mom herself, Street brings a maternal concern to the classroom. “What I want for my children, I want for other children: Access and exposure to information where they can find their truth,” she says.

As an NLP ambassador, Street advocates for news literacy education and support educators who join NLP’s News Literacy Educator Network — NewsLit Nation. This role gives her a new and important way to bring a little extra seasoning to the education system, and to her life.

Black History Month: Pioneering journalists, media

This February, during Black History Month, we’re shining a light on pioneering Black journalists and news media from the past two centuries. Many of these reporters and outlets overcame incredible obstacles and discriminatory systemic structures to report the facts in their communities. Many are also relatively unknown to the news-consuming public. We hope to help change that. Follow our Twitter thread throughout February as we highlight a journalist and/or news outlet each weekday.

We began by highlighting the Freedom’s Journal, the first Black-owned and -operated newspaper in the United States. The four-page, four-column paper debuted in 1827, the same year that slavery was abolished in New York State. Like many of the publications operated by or created for Black Americans that would follow, Freedom’s Journal served to counter racist commentary published in the mainstream press.

Twenty years later, Frederick Douglass and Martin Delaney launched The North Star. The abolitionist newspaper would become the most influential anti-slavery publication of the 19th century, focusing on anti-slavery progress, women’s rights and Black empowerment. The North Star published 565 issues between 1847 and 1851, according to the Library of Congress. In the late 1800s, Black investigative journalism rose to the forefront as Ida B. Wells exposed the widespread practice of lynching, particularly of Black men. Wells’ work is featured in our Checkology® lesson “Democracy’s Watchdog.”

Still publishing today

The 1900s saw the creation of more Black-owned newspapers, including two of the most respected publications that still publish today. Robert Sengstacke Abbott founded The Chicago Defender in 1905, and shepherded its growth into a local paper with a weekly circulation of 16,000 in its first decade. James H. Anderson put out the first edition of the Amsterdam News, a New York paper, on Dec. 4, 1909, with six sheets of paper and a $10 investment. The publication grew quickly to cover not just local stories but national news as well. A year later, in 1910, W.E.B. Du Bois served as the editor of the NAACP’s first issue of The Crisis, its official magazine. It took off from there.

Continuing chronologically through the 1900s, we’re highlighting just some of the many Black journalists that made indelible impacts with their reporting. From Charlotta A. Bass to Ted Poston and on and on, follow our Twitter thread for more throughout February.

New education secretary must prioritize civics education

Strengthening our democracy by transforming civics education

One of the primary purposes of public education is to teach the next generation about the functioning of a democratic society — and to foster its engagement as equal and engaged participants who will seek to preserve and improve democratic norms and practices. But those who lead by falsehoods represent a threat to our democracy, in part because many people lack an understanding of how our system of government works and how they can become informed about it. If we fail to teach civics, our young people — tomorrow’s voters — will be at a great disadvantage. And the fewer people who can engage in rational, fact-based debate, the greater the chance that we will be unable to govern ourselves, jeopardizing the future of our democratic way of life.

We can commit to resolve this problem by making civics the centerpiece of a quality education. An effective civics curriculum must include news literacy at its core to help young people develop critical thinking skills to discern fact from fiction and determine the credibility of the news and other content that bombards them daily. News literacy gives people the ability to become smart, active and engaged consumers of news and information and empowers them to participate in the civic life of their communities and country.

We understand the many challenges that Secretary of Education nominee Cardona faces in overcoming the unprecedented obstacles imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, but this moment is too important to let civics fall by the wayside. As President Biden said in his inaugural address, “We must reject the culture where facts themselves are manipulated and even manufactured.” Cardona can take the lead on this by recommitting the country and our education system to a civics education that has news literacy has a key component.

NLP launches NewsLit Nation, the News Literacy Educator Network

Nationwide community of teachers, librarians and administrators advocate news literacy education

With educators on the frontline of the fight against misinformation, NewsLit Nation provides resources and know-how for this urgent and important work. The network also organizes locally to enable educators to push for news literacy instruction in their schools and communities, says Ebonee Rice, NLP’s vice president of the educator network.

“We’re building an army of news literacy educators to mobilize their peers and create a future founded on facts,” she says. “We’re here to empower educators with the tools they need to actively teach students the abilities to become equal and engaged participants in our democracy.’’

What is NewsLit Nation?

NewsLit Nation:

- Trains teachers, librarians and school administrators across the country to advocate on behalf of a news literacy curriculum.

- Helps you find opportunities for local partnerships and build channels of communication for your communities as local news literacy champions.

- Gives you access to exclusive professional development opportunities, webinars, other training and additional support through online forums and message boards.

- Acts as the resource library for all our news literacy materials for educators.

And, NewsLit Nation includes a network of ambassadors — educators working to create a sense of community in their local and regional school districts. (Thirteen news literacy ambassadors are already working in 10 cities across the country.)

Educators can easily join the network by registering here.

NewsLit Week | Wisconsin students win PSA contest

Students in Lisa Ruehlow’s Media Literacy class at Amery High School in Wisconsin combined creativity and their Checkology® lessons to create public service announcements about the importance of news literacy for young people. And two of them took top honors for the national PSA contest sponsored by the News Literacy Project (NLP) and The E.W. Scripps Company. The new contest was part of National News Literacy Week (Jan. 25-29.) One of Ruehlow’s students won first prize, and another was selected as runner-up.

The winners are:

First prize: Nicholas Hahn, senior

His video featured clips from current events to demonstrate the real — and often harmful — impacts of misinformation. Watch Nicholas’ PSA.

Runner-up: Mary Mallum, senior

She used animated graphics to provide tips for parsing the false from the factual. Watch Mary’s PSA.

NLP and Scripps, sponsors of National News Literacy Week, asked students taking Checkology virtual classroom lessons to submit a 30-second video PSA related to the week’s theme: Get NewsLit fit. The PSA contest aimed to encourage young people to promote news literacy to their peers.

The winning students took a new course that Ruehlow created and taught for the first time last fall. The class of 20 included mostly seniors, plus a few juniors and sophomores. All completed the PSA assignment for class. Throughout the semester the students enthusiastically embraced the topic of news literacy, Ruehlow says.

“I am exceedingly happy that students see the value of the tools they have learned — they are sharing their insights with others, and are quite passionate about it,” she says. “Many have told me that they think this class should be required of every high school student since this topic is so incredibly important to their daily lives.”

The importance of media literacy

When she asked students why they thought media literacy was important, they offered thoughtful responses.

- “Media Literacy is more critical than ever as people spend so much time on social media, where anyone can post something and claim it as ‘news.’”

- “It’s important to know what’s true and how to verify or debunk it for ourselves. With people spending so much time-consuming media, it can help our relationships, our country, and our digital communities by knowing what’s real and not allowing it to evoke such a severe emotional response.”

- “Media literacy is important because being misled by false information can result in harmful or incomplete understandings. That can result in action being taken, such as storming the Capitol.”

Her students clearly grasp the significance and urgency of becoming more news-literate. Ruehlow — and other educators like her — who are dedicated to this work — make that possible.

NewsLit Week | Use ‘PEP’ to talk to conspiracy believers