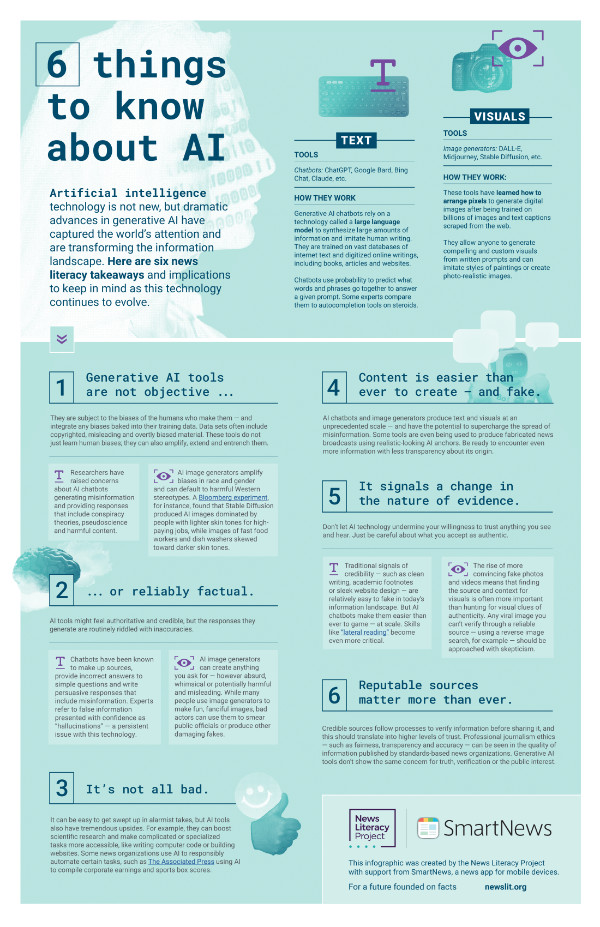

6 things to know about AI

Artificial intelligence technology is not new, but dramatic advances in generative AI have captured the world’s attention and are transforming the information landscape.

This infographic provides an overview of how this technology works and offers six news literacy takeaways to keep in mind as these tools evolve:

- Generative AI tools are not objective: They are subject to the biases of the humans who make them, and any biases in the training data may show up when they are used.

- . . .or reliably factual: AI tools might feel authoritative and credible, but the responses they generate are routinely riddled with inaccuracies.

- It’s not all bad: AI tools also have tremendous upsides. (For example, they can boost scientific research and make complicated or specialized tasks more accessible, like writing computer code or building websites.)

- Content is easier than ever to create — and fake: AI chatbots and image generators produce text and visuals at an unprecedented scale — and have the potential to supercharge the spread of misinformation. Be ready to encounter even more information with less transparency about its origin.

- It signals a change in the nature of evidence: The rise of more convincing photos and videos means that determining the source and context for visuals is often more important than hunting for visual clues of authenticity. Any viral image you can’t verify through a reliable source — using a reverse image search, for example — should be approached with skepticism.

- Reputable sources matter more than ever: Credible sources follow processes to verify information before sharing it, and this should translate into higher levels of trust.

Don’t let AI technology undermine your willingness to trust anything you see and hear. Just be careful about what you accept as authentic.

News Goggles: Karena Phan, The Associated Press

Standards-based news organizations care about getting the facts right. When false claims spread online, journalists and fact-checkers often step in to investigate and share their findings to help set the record straight.

This week, we talk to Karena Phan, a reporter for the news verification team at The Associated Press. Phan discusses the steps she takes to find and debunk misinformation trending online. We examine Phan’s recent fact check on a viral video falsely claiming to show the world’s tallest tree and explore how simple tools — such as a Google search or a reverse image search — can go a long way in separating fact from falsehood. Ready to fact-check like a pro? Grab your news goggles!

Note: Look for this newsletter feature the first Monday of the month. You can explore previous News Goggles videos, annotations and activities in NLP’s Resource Library under “Classroom Activities.”

Resources:

- “Misinformation” (NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom).

- “MisinfoChallenge: Fact-checking 101” (Checkology virtual classroom).

- Infographic: “Eight tips to Google like a pro” (NLP’s Resource Library).

Dig Deeper: Use this viewing guide for the featured News Goggles video to help students take notes on how to think like a fact-checker and verify information online.

News Goggles annotations and activities provide news literacy takeaways on timely topics. These resources feature examples of actual news coverage, including full news reports, headlines, breaking news alerts or excerpts.

This video originally appeared in the March 6, 2023, issue of The Sift® newsletter for educators, which explores timely examples of misinformation, addresses journalism and press freedom topics and examines social media trends and issues. Read archives of the newsletter and subscribe here. Stock music in this video was provided by SoundKit from Pond5.

Have feedback about this resource? Or an idea for a future News Goggles? Please share it with us at [email protected].

News Goggles: Libor Jany, Los Angeles Times

Sources play a key role in reporters’ efforts to gather and publish information of public importance. Documents, images, video and people can all serve as sources in news coverage. When it comes to choosing sources, reporters work to interview the people or entities in a position to know the information they’re looking for. That might include experts, elected officials, everyday people or all of the above.

This week, we talk to Los Angeles Times reporter Libor Jany about his role covering the Los Angeles Police Department. Jany discusses his approach to reporting on public safety and how he develops sources on his beat. We consider some of the ways that sources share information with reporters — including what it means to be on the record, on background and off the record. Jany also sheds light on the steps journalists take to verify information and explains why it’s important to seek out diverse viewpoints and perspectives. Grab your news goggles!

Note: Look for this newsletter feature the first Monday of the month. You can explore previous News Goggles videos, annotations and activities in NLP’s Resource Library under “Classroom Activities.”

Resource: “Practicing Quality Journalism” (NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom).

Idea: Contact a local journalist using NLP’s Newsroom to Classroom program and ask them to discuss how they decide which sources to include in news coverage.

Dig Deeper: Use this viewing guide for the featured News Goggles video to help students take notes on how journalists develop and use sources in news reports.

News Goggles annotations and activities provide news literacy takeaways on timely topics. These resources feature examples of actual news coverage, including full news reports, headlines, breaking news alerts or excerpts.

This video originally appeared in the Feb. 6, 2023, issue of The Sift® newsletter for educators, which explores timely examples of misinformation, addresses journalism and press freedom topics and examines social media trends and issues. Read archives of the newsletter and subscribe here. Stock music in this video was provided by SoundKit from Pond5.

Have feedback about this resource? Or an idea for a future News Goggles? Please share it with us at [email protected].

PitchIt! Student essay contest

PitchIt! Student essay contests happening in Colorado, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania and Texas

Grades: 6-8, 9-12

About

Student voices are catalysts for positive change in schools and communities. You can empower them to be well-informed and civically engaged when you participate in the News Literacy Project’s PitchIt! contest.

This is an authentic way to get middle and high school students to learn about and express their thoughts about current events from a news literacy perspective. In addition to exploring an issue important to them, they can help combat misinformation or work to protect freedom of the press.

To have your students participate in PitchIt! and get the most out of it, use NLP’s free resources and curriculum guides. You choose the top essays from your class to submit for judging and prizes.

Click here for a printable, one-page guide to participating in PitchIt!

It is the ideal time to start using Checkology® and other free resources to prep your students. You can also email your questions to [email protected] for more information.

- Pennsylvania deadline, March 1, 2024: Click here for details.

- Colorado deadline, April 15, 2024: Click here for details.

- Florida deadline, May 24, 2024. Click here for details.

- New York deadline, April 19, 2024: Click here for details.

- Texas deadline, April 26, 2024: Click here for details.

Not in one of these regions? NLP encourages you to contact your local news literacy ambassador or our staff ([email protected]) and adapt our contest rules to create a contest for your learning community.

Curious to what participating teachers had to say?

“PitchIt! utilizes news literacy curriculum to broaden the understanding of how media influences all of us every day. Students then analyze and learn for themselves the power of using information with and without bias. I highly recommend facilitating part or all of the curriculum in classrooms across the board in Social Studies, English, Science, and more. It shows students that language, facts, and biases impact us comprehensively.”

— Renee A. Cantave, iWrite magnet educator, Arthur and Polly Mays Conservatory of the Arts, Miami, Florida

“PitchIt! was a great experience for my students. Not only did it raise awareness among them regarding the importance of good writing and of an important current issue in our community, the culminating event gave contest winners a chance to verbally express their positions, while receiving important feedback.”

— Rolando Alvarez, Coral Way K-8 Center, Miami, Florida

Tired of feeling like you’re working in a vacuum? Sign up for NewsLitNation and our private NewsLitNation Facebook Group to connect and share with other educators across the country passionate about news and media literacy. As a member of NewsLitNation® you’ll receive special perks and the NewsLitNation Insider, our monthly newsletter that keeps you up to date about all things news literacy!

Evaluate credibility using the RumorGuard 5 Factors

Don’t get caught off guard. Recognize misinformation and stop it in its tracks by using RumorGuard’s 5 Factors for evaluating credibility of news and other information. This classroom poster displays the 5 Factors alongside “Knows” and “Dos” for evaluating credibility.

Learn about RumorGuard | Go to RumorGuard | The 5 Factors on RumorGuard

The 5 Factors

- Authenticity. Is it authentic?

The digital age has made creating, sharing and accessing information easier than ever before, but it’s also made it easier to manipulate and fabricate everything from social media posts to photos, videos and screenshots. The ability to determine whether something you see online is genuine, or has been doctored or fabricated, is a fundamental fact-checking skill.

- Source. Has it been posted or confirmed by a credible source?

Not all sources of information are created equal, but it can be easy to glaze over the significant differences while scrolling through feeds online. Standards-based news organizations have guidelines to ensure accuracy, fairness, transparency and accountability. While these sources aren’t perfect, they’re far more credible and reliable than sources that have no such standards. Viral rumors that confirm one’s perspectives and beliefs or that repeatedly appear in social media feeds can feel true, but if no credible source of information has confirmed a given claim it’s best to stay skeptical.

- Evidence. Is there evidence that proves the claim?

Misinformation lacks sound evidence by its very nature — but it often tricks people into either overlooking that fact or into accepting faulty evidence. Many false claims are sheer assertions and lack any pretense of evidence, while others present digital fakes and out-of-context elements for support. Evaluating the strength of evidence for a claim is a key fact-checking skill.

- Context. Is the context accurate?

Tricks of context are one of the most common tactics used to spread misinformation online. Authentic content — such as quotes, photos, videos, data and even news reports — is generally easy to remove from its original context and place into a new, false context. For example, an aerial photo of a sports championship parade from 2016 can easily be copied and reposted alongside a claim that it depicts a political protest that took place yesterday. In this false context, the photo may easily be perceived as genuine by unsuspecting people online. Luckily, there are easy-to-use tools that can verify the original context of most digital content.

- Reasoning. Is it based on solid reasoning?

Misinformation is often designed to exploit our cognitive biases and vulnerability to logical fallacies. These blind spots in our rational thinking can make baseless conclusions feel plausible or even undeniable — particularly when they reinforce one’s beliefs, attitudes and values. Conspiracy theorists, pseudoscience wellness influencers and propagandists commonly rely on flawed reasoning to hold their assertions together. Learning to logic-check claims is an important element in verifying information.

Know and do

Know:

• Standards of quality journalism

• Types of misinformation

• How cognitive biases work

• What makes evidence credible

Do:

• Reverse image search

• Lateral reading

• Critical observation

• Search internet archives

• Practice healthy skepticism

Three types of election rumors to avoid

Elections are the lifeblood of democracy, but political campaigns are often rancorous, controversial and polarizing events. As if the misleading claims and attack ads weren’t challenging enough for the public, bad actors further muddy the waters by pushing disinformation into our social media feeds.

These harmful falsehoods are designed to cause confusion and to undermine people’s faith in American democracy. Election disinformation can be tricky, but the same false narratives and claims tend to get recycled, which can make it easier to spot.

This infographic outlines three common types of election disinformation that are likely to circulate on social media during election cycles in the United States. It also includes tools and tips for locating credible information in your state or district.

Being familiar with recurring election disinformation themes can help inoculate you against the allure of new incarnations and iterations that occur regularly. It can also help you more efficiently debunk them and warn your friends and family members not to get taken in.

The three types of election disinformation this infographic focuses on are:

- “Ballot mule” accusations: A substantial portion of election misinformation revolves around baseless claims of voter fraud. Accusations of people (“mules”) illegally gathering large numbers of fraudulent ballots and delivering them to ballot drop boxes have become particularly common, despite the fact that such allegations lack evidence. More often, people who are authorized to return multiple ballots — such as designated agents for nursing home residents — are incorrectly portrayed as engaging in schemes to swing elections. Be wary of photos and videos of people delivering ballots that are framed as “evidence” of this type of fraud, which is extremely rare.

- Mail-in ballot rumors: Voting by mail is increasingly popular, but people are vulnerable to believing baseless allegations of mishandling ballots, partly because the chain of custody is less direct than with in-person voting. But mail-in voting is no less secure than in-person voting and examples of fraud remain rare (usually involving someone attempting to return a mail-in ballot previously requested by a since-deceased relative or housemate). If you see a claim about fraudulent mail-in voting, be extremely cautious and take time to verify it at least one credible source.

- Poll worker rumors: The increase in livestreams of election workers doing their jobs has given lots of raw fodder to strong partisans looking for anything they can construe as fraud. Keep in mind that there is legitimate and necessary election work that ordinary people are unfamiliar with and don’t entirely understand. Watch out for video clips and images out of context claiming that poll workers are manipulating the vote.

Don’t forget to check out the resources linked throughout the infographic, including ballot trackers, studies of actual fraud (which, again, is extremely rare) and analyses of viral election misinformation.

“Storm Lake” discussion guide on the importance of local journalism

This guide serves as a companion for adult learners and community members viewing the PBS documentary Storm Lake, a film about the struggles of sustaining local journalism and shows what these newsrooms mean to communities and American democracy overall. The guide has three main components: pre-viewing, during viewing and post-viewing activities.

The pre-viewing activities use one or more essential questions to focus on viewers’ engagement with news and their opinions about its relationship to their community and to American democracy. The essential questions are:

- What is news?

- What role does news play in your family members’ lives? In your community?

- Is news important in a democracy? Why or why not?

The during viewing portion includes discussion questions that can be completed whole or in-part, individually, or in small groups. These questions include:

- Is profit a motivation for the [Cullen] family? Why or why not?

- Art Cullen: “A pretty good rule is that an Iowa town will be about as strong as its newspaper and its banks. And without strong local journalism to tell a community’s story, the fabric of the place becomes frayed.”

- a. In your own words, what point is being made in this quote?

- b. Do you agree? Why or why not?

- c. How does this quote fit into your definition of news and its role in the community?

The post-viewing activities return to the essential questions raised prior to viewing and seek to extend engagement with local journalism. These options include keeping a news log for a week and evaluating a source (log included in the guide), interviewing family or friends about their news habits, engaging directly with local news organizations on social media or writing a letter or email to an editor with a suggestion for a story.

News Goggles: Seana Davis, Reuters

News Goggles annotations and activities provide news literacy takeaways on timely topics. These resources feature examples of actual news coverage, including full news reports, headlines, breaking news alerts or excerpts.

This video originally appeared in the March 7, 2022, issue of The Sift® newsletter for educators, which explores timely examples of misinformation, addresses journalism and press freedom topics and examines social media trends and issues. Read archives of the newsletter and subscribe here. Stock music in this video was provided by SoundKit from Pond5.

Misinformation thrives during major news events and can spread rapidly on social media by tapping into people’s beliefs and values to provoke an emotional reaction. Pushing back against falsehoods in today’s information environment is no small task, but a few simple tools can go a long way in the fight for facts. This week, we talk to Seana Davis, a journalist with the Reuters Fact Check team, about her work monitoring, detecting and debunking false claims online.

Misinformation often stems from “a grain of truth,” Davis said. “So it’s all about trying to weed out what is true and what is not.”

Davis sheds light on some common ways that viral falsehoods spread — including through miscaptioned videos and digitally altered headlines — and demonstrates how to fact-check false claims like a pro, using digital verification techniques such as reverse image search and advanced searches on social media. Grab your news goggles!

Resources:

- “Misinformation” (NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom)

- Reverse image search tutorial (Checkology virtual classroom)

- Infographic: “Eight tips to Google like a pro” (NLP’s Resource Library)

- Expert mission: “Can you search like a pro?” (Checkology virtual classroom).

Dig deeper: Use this viewing guide for the featured News Goggles video to help students examine how to recognize and debunk some common types of misinformation online.

Have feedback about this resource? Or an idea for a future News Goggles? Please share it with us at [email protected].

How to speak up without starting a showdown

Stepping into the role of fact-checker when it comes to loved ones can be tricky and stir strong emotions, so it’s worth preparing for — especially as more falsehoods seep across social media and into family and friend group chats.

While every scenario is different, following some general best practices can help keep the conversation civil and make the interaction worthwhile. Use these six tips — with some helpful phrases for getting started — as a guide on how to speak up without starting a showdown. It may not be easy, but talking to loved ones about false or misleading content can help them think twice about what to share in the future.

News Goggles: Chasing scoops and verifying raw information

News Goggles annotations and activities offer news literacy takeaways on timely topics. These resources feature examples of actual news coverage, including full news reports, headlines, breaking news alerts or excerpts.

This News Goggles resource originally appeared in a previous issue of The Sift newsletter for educators, which explores timely examples of misinformation, addresses journalism and press freedom topics and examines social media trends and issues. Read archives of the newsletter and subscribe here.

On Jan. 3, 2021, The Washington Post broke the news about a recorded telephone conversation between President Donald Trump and Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, during which the president pressed Raffensperger to “‘find’ enough votes to overturn his defeat” to President-elect Joe Biden. Other news reports on the leaked recording soon followed, with news organizations such as CNN crediting the Post as being the first to break the story.

The Post’s initial reporting — labeled “exclusive” — is, by any standard, a major story, and has even been called “the scoop of the year.” In journalism, a “scoop” refers to an important news story first reported by a particular news organization or reporter(s). (Journalists call this “breaking” the story.) In this edition of News Goggles, we’re going to explore how journalists balance the desire to be first on a competitive, quickly developing story with the need for accuracy. Let’s examine the original Post report and analyze how other news organizations chased and verified this scoop. Grab your news goggles. Let’s go!

★ Featured News Goggles resource: These classroom-ready slides offer annotations, discussion questions and a teaching idea related to this topic.

Note: Information “leaked” to the press has historically played an important role in watchdog journalism to hold the powerful accountable. The New York Times published journalist Neil Sheehan’s account of how he obtained the leaked Pentagon Papers, a “blockbuster scoop” on America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Sheehan, who died on Jan. 7, 2021, asked that the story remain unpublished while he was alive.

Related: “Trump’s phone call to Georgia was illegal, immoral or unconstitutional. Here’s how some journalists decide what to call it.” (Kelly McBride, Poynter).

Discuss: How should journalists balance speed and accuracy in reporting? Why is information sometimes “leaked” or shared with journalists? Can journalists trust the information that is leaked to them? What are some ways to fact-check or verify raw information, such as a phone recording? Why might standards-based news organizations pursue certain “scoops” over others? How is the Post’s report an example of watchdog journalism?

Idea: Ask students to put themselves in reporters’ shoes and imagine that someone had sent them a copy of the phone recording. What should they do next? Should they immediately report on the recording and release it, or should they take other steps to verify this piece of raw information? Who could they contact to make sure it is authentic? How should they determine if the source of the recording is credible? Finally, how should they decide which excerpts of the hour-long call are most important to feature in a news report to be fair and accurate?

Resources: “Practicing Quality Journalism,” “Democracy’s Watchdog,” “What is News?” and “InfoZones” (NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom).

Have feedback about this resource? Or an idea for a future News Goggles? Please share it with us at [email protected]. You can also use this guide for a full list of News Goggles from the 2020-21 school year for easy reference.

Seven standards of quality journalism

The standards and practices of quality journalism are complex, numerous and dynamic, and are implemented differently by different journalists and different news organizations under different circumstances on different pieces of journalism. See a trend here? Practicing journalism is complicated and nuanced. Still, the general purpose behind the standards is the same: to produce the most accurate, fair and useful information possible.

Some journalism standards are obligatory (such as the prohibition against making things up) and quantifiable (such as newsroom policies about the use of anonymous sources), while others are aspirational (such as the attempt to eliminate bias and to be as fair and accurate as possible) and require judgment and discussion to apply (such as assessing newsworthiness, evaluating sources and determining fairness).

By introducing students to the major standards of quality journalism, and helping them understand their nature and rationale, you’re providing them with conceptual and analytical tools that they can use to evaluate the credibility of the information they encounter daily and, in some cases, to critically respond to it. This knowledge can also activate a wide variety of high-level news literacy discussions in your classroom and beyond.

The seven primary standards of quality journalism and their descriptions are included in the poster linked below. This poster is adapted from a highly interactive, immersive learning experience in our Checkology® virtual classroom in which students are placed in the role of a rookie reporter on the scene of a breaking news event and learn the standards of quality journalism by “covering” the story. They are guided by their editor and a veteran reporter back in the newsroom throughout the process, and can use their virtual notebooks to see their progress in following the standards. At the end of the lesson, they build the story, selecting the most appropriate headline, lead, image and more. Use this poster with the Checkology lesson “Practicing the Standards of Quality Journalism” or on its own.