Vaccines and Misinformation | How to interpret data on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines

This article is part of a series presented by our partner SAS that explores the role of data in understanding COVID-19. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field.

If there’s one thing people want to know most about a vaccine, it’s this: Does it work?

So naturally, as COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials were being completed and vaccines were being considered for emergency use authorization, the numbers that featured most heavily in the news were efficacy rates.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine boasted an efficacy rating of 95%, Moderna 94% and Johnson & Johnson 72%. But what do those numbers really mean? How can individuals use these numbers to make decisions for their families?

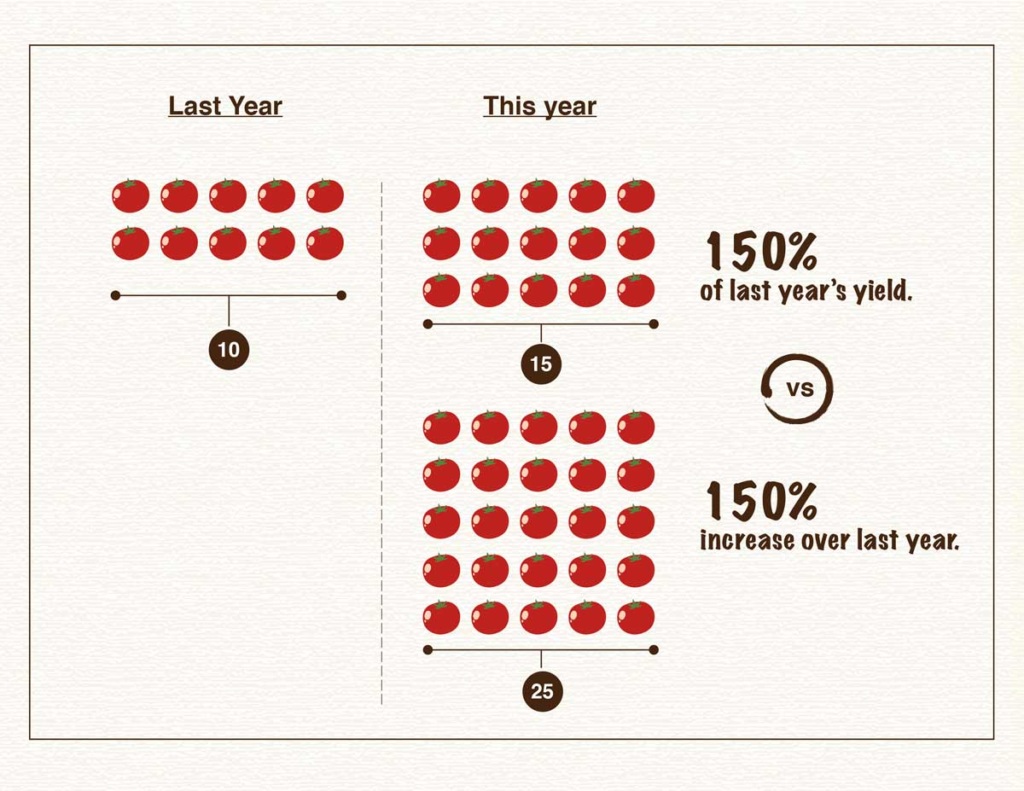

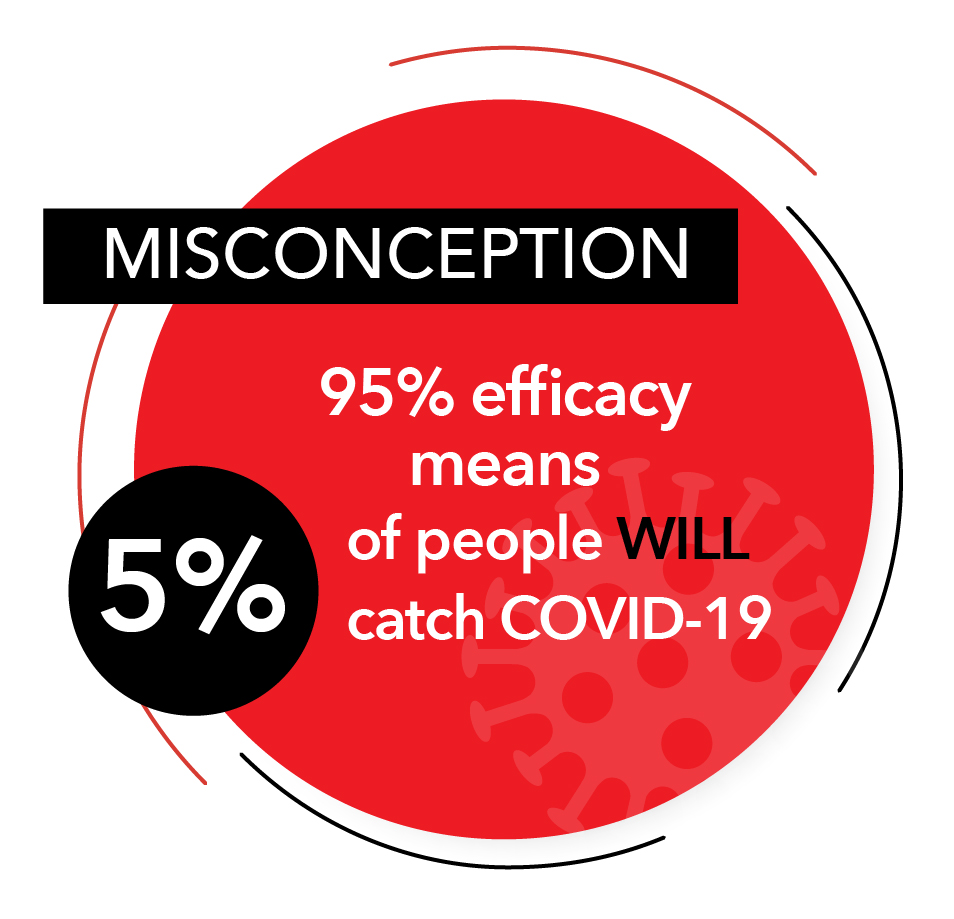

One common misconception is that a 95% efficacy rate means that 5% of the participants in the trial contracted COVID-19, and that similarly, 5% of the vaccinated population will catch it as well. That is not the case. The purpose of the efficacy rating is to show how much the RISK of catching the disease is reduced.

One common misconception is that a 95% efficacy rate means that 5% of the participants in the trial contracted COVID-19, and that similarly, 5% of the vaccinated population will catch it as well. That is not the case. The purpose of the efficacy rating is to show how much the RISK of catching the disease is reduced.

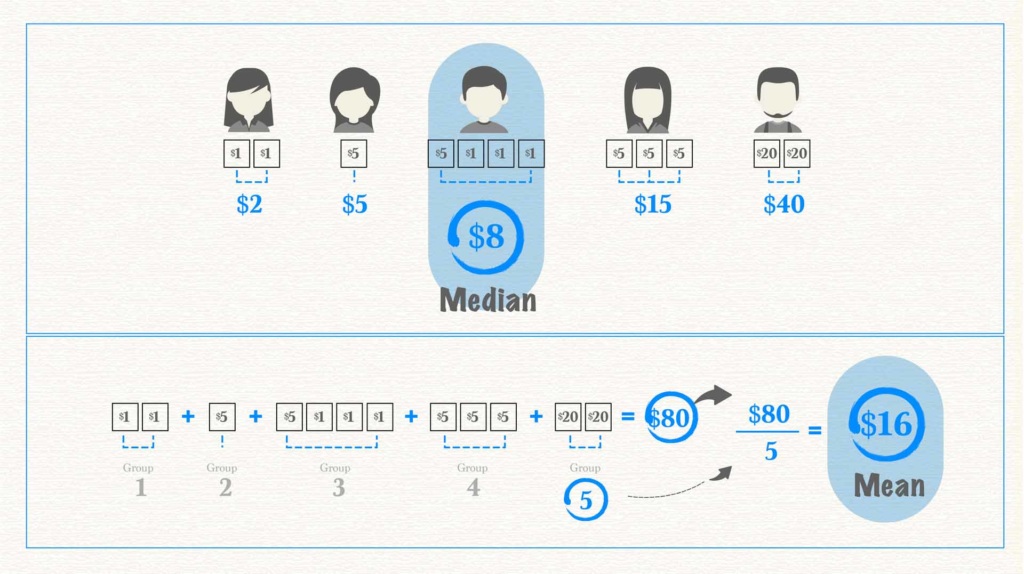

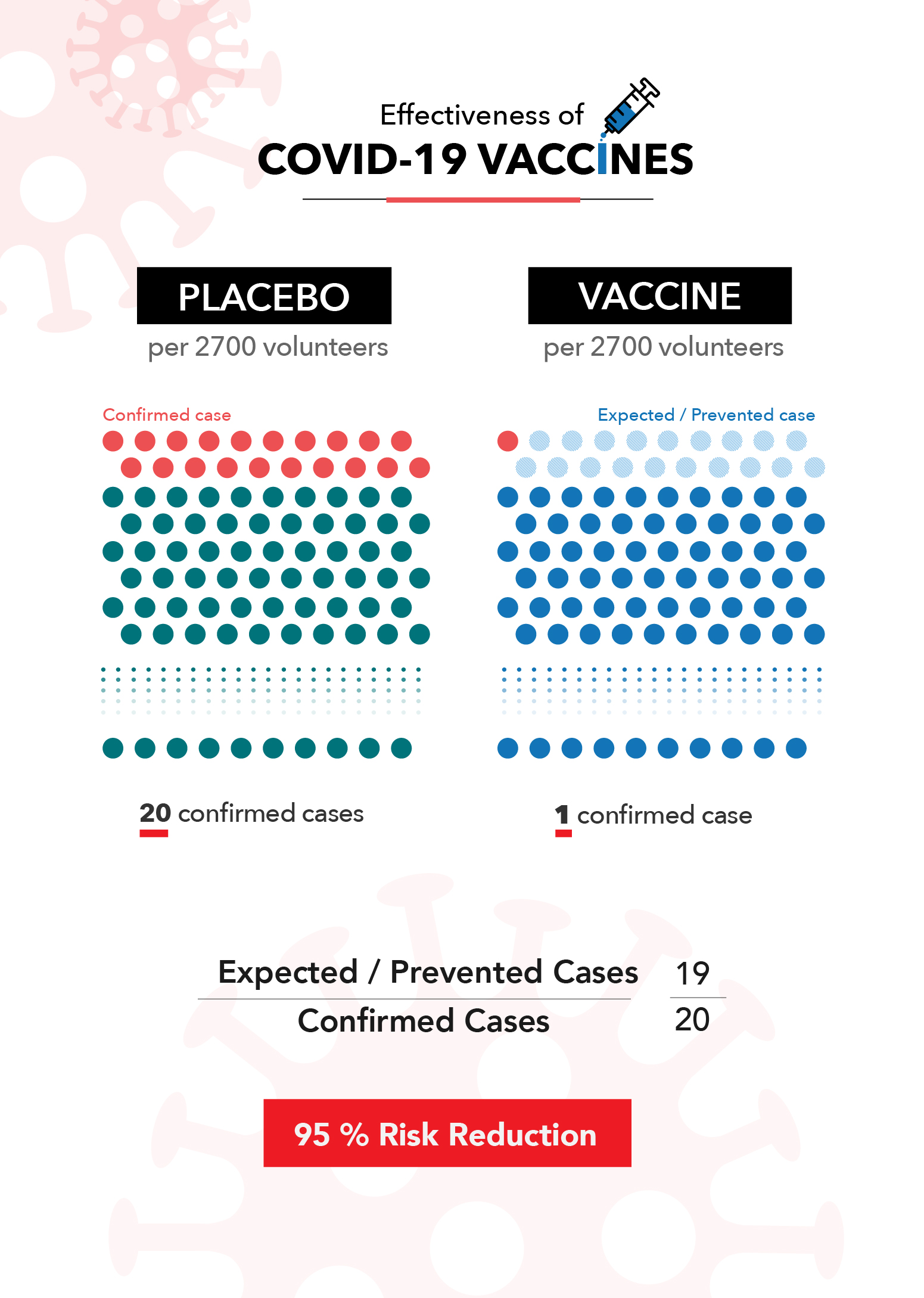

Let’s look at what this means using the Pfizer-BioNTech clinical trial. According to their released data, 160 out of the 21,728 people in the placebo group tested positive for COVID-19. Conversely, more than a week after receiving the second vaccine dose, only eight out of 21,720 people tested positive.

This means that over the course of the trial, it could be expected that the average unvaccinated person had a 0.7% chance of catching COVID-19. Alternatively, if you had received the Pfizer vaccine, you had a 0.04% chance of catching it. This is where their 95% efficacy rating comes from. It means that there were 95% fewer cases than would have been expected if the trial participants were not vaccinated.

Clinical trials can be hard to compare to one another because they occur during different time periods, in different places and have different definitions and criteria. This is a major reason health officials caution against comparing the efficacy numbers of different vaccines against one another. Small variances in the details of the trial can impact the final numbers.

The unique nature of clinical trials can also lead people to wonder how the vaccines perform in the real world, especially when issues like new variants come into play. Thankfully, we’re already seeing evidence that the real-world effectiveness of these vaccines matches up with the numbers reported in their clinical trials.

Now that a significant portion of the population is fully vaccinated, we can also examine recent, in-the-wild data to further understand how the vaccines reduce risk. We know that the vaccines aren’t perfect, and the CDC is actively collecting data on breakthrough cases (confirmed infections among vaccinated people).

As of April 26, the CDC reported 9,245 infections among the more than 95 million Americans who had been fully vaccinated. Using historical data* as a benchmark, an average of 264 vaccinated Americans tested positive for COVID-19 per day over the last two weeks of April. During that same period, the U.S. saw an average of 62,800 new cases per day among the entire population. That roughly equates to three cases per 1 million vaccinated Americans per day, compared to about 260 cases per 1 million unvaccinated Americans per day. It’s not perfect, but it represents a significant reduction in risk.

During that same two-week period, the U.S. recorded 8,926 total deaths due to COVID-19, 58 of which were fully vaccinated individuals. Given what we know about the size of the vaccinated and unvaccinated population, this means that vaccines likely saved at least 3,000 lives in those two weeks alone. The total lives saved is likely even higher, when one accounts for the fact that the demographics of the first groups of vaccinated Americans were among the most vulnerable for severe complications and death due to COVID-19.So what does all of this mean as you consider whether the vaccine is a good choice for you and your family? Getting the vaccine does not offer a guarantee that you won’t catch the disease or get seriously ill from it. But it does offer a very significant reduction of risk.

For example, consider that wearing seatbelts in a car is estimated to carry a 45% reduction in risk of death, and doing so is a choice most of us would make whether it was the law or not. Even if we believe our risk of an auto accident is low, we still make a conscious choice to further reduce the possibility of severe injury. Seatbelts don’t offer 100% protection, and neither do COVID-19 vaccines, but the data shows the added safety is worth it.

* As of May 14 the CDC has changed how they report breakthrough cases. Visit the CDC website for up-to-date information.

About SAS: Through innovative analytics software and services, SAS helps customers around the world transform data into intelligence.

About SAS: Through innovative analytics software and services, SAS helps customers around the world transform data into intelligence.

Vaccines and Misinformation | Understanding how misinformation can fuel vaccine hesitancy

Misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine is contributing to a hesitancy to get vaccinated. In an effort to separate fact from fiction and provide a better understanding of the reasons for that reluctance, we’re going to spend this week focusing on the issue and providing trustworthy information about it.

NLP’s staff members snapped selfies while getting their vaccine shot.

We’re starting with an update to our COVID-19 webpage, which includes links to credible health care organizations and reporting that have debunked many of the myths surrounding the vaccines. Additional resources dive more directly into the reasons people have expressed for not getting a shot. Our friends at SAS are providing context to the data about the vaccines that we hope will show you how effective they’ve been in preventing the spread and harm from the virus.

We’re also producing a special episode of our podcast Is that a fact? We’ll get insight from Dr. Erica Pan, California state epidemiologist and deputy director for the Center for Infectious Diseases at the California Department of Public Health, and Brandy Zadrozny, a senior reporter for NBC News who covers misinformation, extremism and the internet. They share their expertise on how the vaccines were created, their effectiveness, the impact of misinformation on vaccine hesitancy and how anti-vaxxers have used the pandemic to sow more confusion and grow their ranks.

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced new guidelines stating that “fully vaccinated people no longer need to wear a mask or physically distance in any setting,” along with some specific exceptions. It’s clear that the vaccinations are saving lives, reducing the health risks of the virus and helping us return to some semblance of normalcy. We hope that by providing this information, you can help the people in your community make informed decisions about getting the vaccines. Please share these resources, and remember, the best advice we can offer people who are hesitant to get a vaccine is to suggest that they talk to their health care provider about the benefits and risks of getting vaccinated.

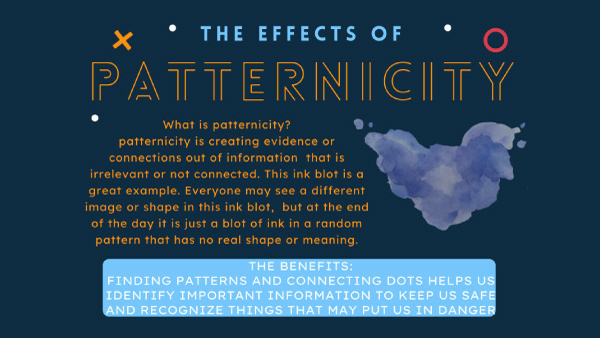

Patternicity contest demonstrates mastery of key concept

Our brains are built to look for patterns, and we tend to see them everywhere. We look up at a cloud and see the shape of a cat. Or we recognize the outline of a face in a puddle.

Patternicity is the term for this tendency to perceive meaningful patterns and connections among unrelated events. It’s often a harmless diversion. However, it can be used to support a belief that is otherwise lacking in evidence, like a conspiracy theory.

NLP created a contest to measure Checkology® students’ understanding of patternicity — an important news literacy concept. Students submitted a poster or infographic explaining the dangers of creating or believing false evidence rooted in patternicity.

Grace Bradley of Missouri won NLP’s first patternicity contest. The senior is a student in Nicole Cusick’s English class at Lee’s Summit West High School. Cusick taught patternicity in her media studies course as part of a segment on conspiratorial thinking. The course asks students to seriously evaluate media consumption and media’s role in society.

“When I saw the contest, I originally thought it would be a fun way to learn about conspiracy theories. After a closer look, I thought it would be a perfect way to have an authentic assessment of their learning about how conspiratorial thinking develops and the impact it can have on us and our society,” Cusick says.

Clear definition of patternicity

Kim Bowman, NLP’s user success associate, says Grace’s entry offered a clear definition of what patternicity is and why we tend to look for patterns. “Grace skillfully explained the dangers of this illusory perception (when it leads to conspiratorial thinking) using topical examples. In addition to being very informative, the final product was creative and unique with both the layout and images.”

“It was such a fun assignment and project, and I’m so proud of my infographic, so I’m really happy I won,” Grace says.

She also enjoyed using Checkology to study news literacy. For example, she likes the ease of use, ability to learn at her own pace and relevancy of the lessons. “I like how much effort they have put in to making it more interesting and interactive as well. They’re really moving with the times. Everything is tailored to high school students, and it really shows,” says Grace.

And the contest itself motivated students, Cusick says. The recognition helped them see the payoff from their hard work. It also gave students a new perspective about what they learn and why. “They are seeing how the skills of my English classroom are applicable to their lives outside of the classroom as well,” she says.

Click image thumbnails above to view the full posters created by Gabby Reynolds, Noah Stice and Miyabi Schroth (left to right).

The patternicity contest runners-up included two of Grace’s classmates: Gabby Reynolds and Noah Stice. Miyabi Schroth of Berkeley, California, is the other runner-up. Schroth is a student in teacher-librarian Melanie Ford’s class at Longfellow Arts and Technology Middle School, where the eighth-grader is also a library assistant.

Grace and Cusick will receive an assortment of NLP-branded swag in recognition of their work.

Celebrating AAPI journalists and news media

More than 40 years ago, the United States first celebrated the heritage of Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) with a commemorative week in May 1979. But this year, amid disturbing violence and abuse targeted at Asian-Americans, immigrants and other people of color, appreciating the culture and contributions of the AAPI community is more important than ever.

Photo credit: Franz Lopez on Flickr, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

For Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month, NLP is highlighting AAPI journalists and news organizations — past and present — on social media. We begin with Rappler co-founder and CEO Maria Ressa. She received the 2021 UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize on the eve of World Press Freedom Day, May 3. Ressa, a Filipina-American journalist, and her team continue their unflinching coverage of President Rodrigo Duterte’s authoritarian rule in the Philippines despite harassment, threats and jail time. In 2020, Ressa was a guest on NLP’s podcast Is that a fact?, where she discussed her work and why she presses on despite the risks. “… you don’t wake up and you say, ‘I’m going to fight for press freedom.’ I never did. I just did my job,” she told us.

Important AAPI milestones

So why is May Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month? The U.S. Congress selected this time of year to celebrate the AAPI community because of important milestones. “The month of May was chosen to commemorate the immigration of the first Japanese to the United States on May 7, 1843, and to mark the anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869. The majority of the workers who laid the tracks were Chinese immigrants,” according to the Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month website. Educators will find lessons plans and other classroom-ready resources for teaching about AAPI heritage on the site.

And be sure to follow our thread on Twitter throughout the month as we focus on the impact of AAPI journalists and news organizations @NewsLitProject.

Behind the headlines: Blocking press freedoms

This article is from a previous issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

By Suzannah Gonzales

Journalism — “arguably the best vaccine against the virus of disinformation” — is obstructed in a majority of countries around the world, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and its new press freedom ranking.

The 2021 World Press Freedom Index, an annual ranking of 180 countries and territories, showed that journalism “is totally blocked or seriously impeded in … 73% of the countries evaluated.” The “data reflect a dramatic deterioration in people’s access to information and an increase in obstacles to news coverage,” an overview of the ranking said. COVID-19 is being used to block availability to sources and reporting on the ground, making it hard to cover controversial stories. RSF questioned whether access will improve once the pandemic ends.

In addition, RSF noted a troubling measure of public mistrust of journalists, citing the results of a survey in 28 countries called the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer. It found that nearly 60% of those who responded believe “journalists deliberately try to mislead the public by reporting information they know to be false” when in actuality, journalism combats “infodemics” of misinformation and disinformation, RSF said.

The United States advanced one place (to 44) with its press freedom categorized as “fairly good,” RSF said, despite unprecedented numbers of assaults against and arrests of journalists (about 400 and 130, respectively).

Norway remained at the top of the list for the fifth year, and Finland held on to its second-place spot while Sweden reclaimed its third-place ranking. Totalitarian countries once again claimed the bottom three places — Turkmenistan (178), North Korea (179) and Eritrea (180). Malaysia, which recently enacted a law against what authorities deem false content, dropped the most in the ranking — 18 spots to 119.

Related:

- “Governments are using Covid-19 as an excuse to crack down on press freedom” (Sara Torsner and Jackie Harrison, Nieman Lab).

- “Guilty Verdict for Hong Kong Journalist as Media Faces ‘Frontal Assault’” (Austin Ramzy and Tiffany May, The New York Times).

- “Very telling/chilling response by Hong Kong government to latest RSF press freedom rankings” (Timothy McLaughlin, Twitter).

- “Listening to what trust in news means to users: qualitative evidence from four countries” (Reuters Institute).

Behind the headlines: Values, trust and media

This article is from a previous issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

By Hannah Covington

It can be tempting to view the public’s distrust of the news media as simply a matter of political differences. But a recent study offers new ways of looking at and addressing the “media trust crisis.” It suggests that not all Americans embrace the core values that journalists follow in their work, and that this misalignment — rather than partisanship — may help better explain media trust divides. For example, people who value authority and loyalty may be wary of journalists’ role as watchdogs over the powerful.

“When journalists say they are just doing their jobs, in other words, the problem is many people harbor doubts about what the job should be,” the report said.

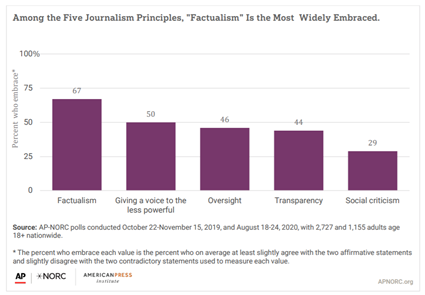

The study was released on April 14 by the Media Insight Project — a collaboration of the American Press Institute and The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research — and examined “public attitudes toward five core values of journalistic inquiry.”

Most agree on importance of facts

These values include acting as watchdogs over powerful people; making information open and transparent; valuing facts in pursuit of truth; offering a voice to those lacking power; and shining light on societal problems.

Only 11% of Americans fully embrace all five of these principles, the study found. The importance of facts in pursuit of truth attracted the most widespread support (67%), while just 29% of Americans embraced spotlighting social problems as an effective way to solve them. Distrust among these groups, the study points out, “goes beyond traditional partisan politics.”

The study highlights ways that news organizations can rebuild trust without compromising core values. Simple tweaks to headlines, first sentences and story framing, for instance, can go a long way to broaden the appeal of news reports among a wider audience.

Related:

- “American Views 2020: Trust, Media and Democracy” (Gallup and Knight Foundation).

- “Americans See Skepticism of News Media as Healthy, Say Public Trust in the Institution Can Improve” (Pew Research Center).

Behind the headlines: Clarity or deception?

This article is from a previous issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

Written by: Peter Adams

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis answers questions about his state’s COVID-19 response at a press conference at the Urban League of Broward County on April 17, 2020.

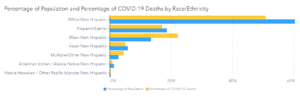

An April 4 report from the long-running CBS News newsmagazine 60 Minutes on disparities in Florida’s vaccine rollout has touched off a wave of criticism questioning the piece’s accuracy and fairness.

The controversy stems from the report’s unsupported suggestion that Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis used the state’s vaccination program to engage in a “pay-to-play” scheme with the supermarket chain Publix when he announced a distribution partnership with the company in January, shortly after it donated $100,000 to his political action committee.

But critics of this segment of the report say it failed to provide substantive evidence of wrongdoing and mischaracterized key details. The report also included footage from a press briefing at which 60 Minutes correspondent Sharyn Alfonsi asked DeSantis about the Publix relationship. However, important parts showing DeSantis denying wrongdoing (at 32:30 in footage of the briefing) weren’t included in the clip. The director of the Florida Division of Emergency Management, Jared Moskowitz, and Palm Beach County Mayor Dave Kerner, who are both Democrats, have backed up the governor’s account.

CBS News defended the edits and stands by the report. At the conclusion of its April 11 episode, 60 Minutes acknowledged criticism of its report and read several letters from viewers. DeSantis, meanwhile, has responded to the incident by going on the offensive, broadly accusing “partisan corporate media” of maliciously trying to damage him.

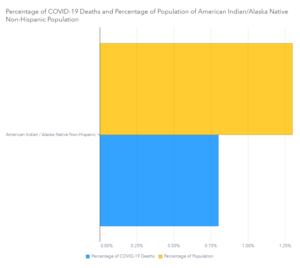

Note: Most of the 60 Minutes report presented accurate information about well-documented racial and economic disparities in the state’s COVID-19 vaccination distribution. But the controversy over the DeSantis allegations overshadowed that reporting.

Also note: CBS said DeSantis declined to be interviewed by 60 Minutes for the report.

Related:

- “Opinion: ‘60 Minutes’ embraces innuendo in Ron DeSantis story” (Erik Wemple, The Washington Post).

- “Not everything was wrong with the ‘60 Minutes’ story on Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and COVID-19 vaccines” (Tom Jones, Poynter).

- “Ron DeSantis is Taking His 60 Minutes Feud All the Way to the Bank” (Charlotte Klein, Vanity Fair).

- “Why Being ‘Anti-Media’ Is Now Part Of The GOP Identity” (Meredith Conroy, FiveThirtyEight).

Discuss: Can journalists include everything a source says in their reporting? How should journalists decide what portions of interviews to include and which to leave out?

Idea: Use this video comparison from NLP to highlight for students the edits 60 Minutes made to the governor’s response to Alfonsi’s question. Do they agree with CBS’ claim that these were justifiable edits made for clarity? Or do they agree with claims by DeSantis that the editing was deceptive and unfair?

Journalist’s classroom visit high point of the year for California sixth-graders

NPR journalist Hannah Bloch is used to asking questions, but during a virtual visit with 80 sixth-graders at Chaparral Middle School in Diamond Bar, California, she was the one peppered with them.

The conversation with Bloch, lead digital editor on NPR’s international desk, was the highlight of a media literacy component that educator Sherry Robertson developed for her language arts class.

“Speaking with Sherry Robertson’s class was a delight. The students were so engaged (even over Zoom, which I expected might be tough). Their questions were thoughtful, and I loved their genuine curiosity about journalism and what it’s like being a journalist,” Bloch says.

Robertson arranged the January visit through the News Literacy Project’s Newsroom to Classroom program. Part of the Checkology® e-learning platform, the program enables educators to invite vetted journalist volunteers to visit their classrooms in person or remotely.

“I felt very passionate about creating a unit on this. The younger we start, the better,” Robertson says. “I’m on a mission to do my part in the world to make my kids literate online.”

Before the visit, Robertson’s students completed the Checkology lessons “InfoZones” and “Arguments & Evidence.” They then submitted questions to Bloch ahead of time through the platform, Padlet.

Inspiring visit

Introducing a new subject area has both challenged and inspired Robertson. “As educators, we weren’t trained to teach this,” she says. “This is new for me. I’m teaching them something I’m learning at the same time.”

Bringing in a subject matter expert was a real help. The conversation with Bloch covered several topics, from what inspired her to become a journalist, to how she determines whether a story is credible, to which fast food restaurant she recommends.

“It was so amazing. She was fantastic and went out of her way to answer my kids’ questions,” Robertson says. And the conversation with a working journalist was eye-opening for her students. “She’s so accomplished, and here she is talking to them as equals. This was something my kids could aspire to. Journalism could be attainable to them. I don’t think they realized it,” she adds.

In a year when distance learning has posed significant challenges to educators, parents and kids, Robertson was able to easily arrange the visit with Bloch, who lives on the East Coast. And it was a natural fit given that everyone has essentially been “living” online since the pandemic began.

Robertson also wanted to ensure her students enjoyed their first year in middle school, despite the circumstances. She sought to keep them engaged and provide something fun. Bloch’s visit was just that. “This was literally the best experience my kids had this year,” Robertson says.

For Bloch, the visit was also a delight. “It was a pleasure to have the opportunity to spend that time with them and I’m thrilled to hear that they enjoyed it, too. And I have so much respect for the work teachers like Ms. Robertson are doing at this most challenging of times,” she says.

Behind the headlines: Sexism in journalism

This article is from a previous issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

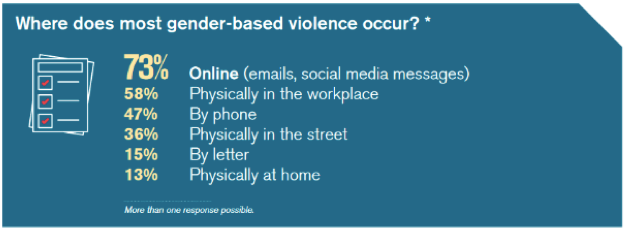

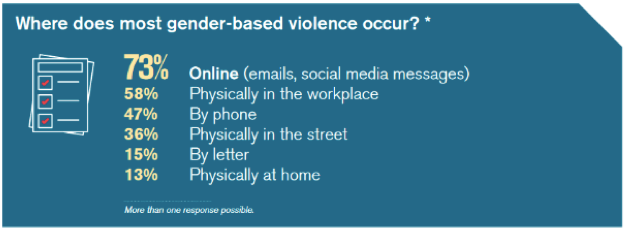

Women working as journalists increasingly face gender-based violence outside of their newsrooms, including a barrage of threats and hate online. But they also endure it inside their workplaces, from discrimination to sexual assaults and harassment, according to a new Reporters Without Borders (RSF) report detailing the toll sexism has taken on journalism.

“The two-fold danger to which many women journalists are subjected is far too common, not only in traditional reporting fields as well as new digital areas and the Internet, but also where they should be protected: in their own newsrooms,” the report said.

Reporters Without Borders “Sexism’s Toll on Journalism” report, March 8, 2021

Published on March 8 — International Women’s Day — the report includes RSF’s analysis of 112 responses to questionnaires sent to its global correspondents and journalists who cover gender, and collected between July and October 2020.

The trauma female journalists experience due to violence both in and out of the newsroom silences victims and leads some to close their social media accounts or even resign, the report found. Issues affecting women “become invisible” in news coverage when there aren’t enough women in top leadership positions, the report said: “The lack of multiple viewpoints within media organisations has major editorial consequences, including in the representation of women in the content offered to the public.”

Note: A separate March 8 report by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism revealed that 22% of top editors at 240 major news organizations are women.

Related:

- “New York Times Defends Reporter Taylor Lorenz From Tucker Carlson’s ‘Cruel’ Attack” (Jordan Moreau, Variety).

- “Carlson, Times tussle over online harassment of journalist” (David Bauder, The Associated Press).

- “Maria Ressa: Fighting an Onslaught of Online Violence” (International Center for Journalists).

- “UNESCO launches campaign to end online violence vs women journalists” (Rappler).

- “Malign Creativity: How Gender, Sex, and Lies are Weaponized Against Women Online” (Wilson Center).

Behind the headlines: Atlanta shootings coverage fallout

By Suzannah Gonzales and Hannah Covington

This article is from this week’s issue of our Get Smart About News newsletter for the general public, which explores timely examples of misinformation as well as press freedom and social media trends and issues. Subscribe to our newsletters.

News coverage of the March 16 fatal shootings at Atlanta-area spas that occurred amid a recent spate of anti-Asian violence across the country spurred important debates over journalism ethics and news decisions — especially as the story first unfolded. Questions and criticisms of coverage highlighted several notable issues, including the bias and credibility of law enforcement sources; the need for more diverse news organizations, journalists and sources; and hesitation by newsrooms to call the shootings a “hate crime.”

As the story developed, the Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) published guidance for newsrooms covering the shootings. Its recommendations include providing context on the recent increasing violence, and understanding the history of anti-Asian racism. It also underscored the need to consult Asian American and Pacific Islander expert sources and to be careful with language that could contribute to “the hypersexualization of Asian women.”

AAJA reported that some newsrooms have questioned whether Asian American and Pacific Islander journalists will show bias or are “too emotionally invested” to cover the shootings. Calling such reports “deeply concerning,” it urged news organizations to empower these journalists “by recognizing both the unique value they bring to the coverage of the Atlanta shootings and the invisible labor they regularly take on, especially in newsrooms where they are severely underrepresented.”

Note: AAJA also released a pronunciation guide for Asian victims of the shootings.

Related:

- “The rush to report on Atlanta-area shootings amplified bias in news coverage” (Doris Truong, Poynter).

- “Connie Chung: The media is miserably late covering anti-Asian violence” (Alexis Benveniste, CNN Business).

- “‘Enough Is Enough’: Atlanta-Area Spa Shootings Spur Debate Over Hate Crime Label” (Bill Chappell, Dustin Jones, NPR).

- “Why don’t we know more about the Atlanta shooting victims?” (Ariana Eunjung Cha, Derek Hawkins and Meryl Kornfield, The Washington Post).

- “Teen Vogue’s New Top Editor Out After Backlash Over Old Racist Tweets” (Maxwell Tani, Lachlan Cartwright, The Daily Beast).

Statement: Base proposed voting measures on facts, not falsehoods

As numerous states consider steps to change the way voters participate in elections, we urge elected officials to base their actions on credible evidence.

We believe that the right to vote is an essential act of an informed citizenry. But legislation premised on widespread disinformation about the 2020 election — including baseless voter fraud claims and conspiracy theories — runs counter to our values and would do lasting harm to voting rights, which are among the most sacrosanct tenets of American democracy.

In a joint statement in November, two federal election security agencies assured the public that the 2020 election was ‘“the most secure in American history.” They noted: “While we know there are many unfounded claims and opportunities for misinformation about the process of our elections, we can assure you we have the utmost confidence in the security and integrity of our elections.”

NLP’s work is rooted in the belief that facts are essential to making sound decisions. That’s why we’re calling on legislators to weigh whether proposed laws represent a response to demonstrated problems with existing voting infrastructure and procedures. While we welcome changes that improve the fairness, transparency and accessibility of elections, we oppose laws based on disproven allegations and manufactured narratives that place unnecessary burdens and restrictions on Americans’ right to elect their leaders and hold them accountable.

The last election saw the largest voter turnout since 1900, and as supporters of an engaged and well-informed voting public, we will continue our work to ensure that people know how to recognize fact from fiction and to use that knowledge to exercise their democratic rights.

CNN’s Abby Phillip joins board of the News Literacy Project

“Abby brings us exceptional credentials as a journalist as well as a fresh perspective,” said Alan C. Miller, founder and CEO of NLP, the nation’s leading nonpartisan education nonprofit. “With her experience, we anticipate that she will contribute valuable insights to the board. We look forward to working with her to expand our reach and impact at this crucial moment for the country’s democracy.’’

Phillip expressed a strong commitment to NLP’s work. “The mission of the News Literacy Project has always been essential to a functioning democracy, but it is needed now more than ever,” she said. “I’m grateful for the opportunity to serve on the board of this great organization as it continues in its work of helping people navigate the modern information environment. As a journalist, I view the work of the News Literacy Project as a perfect complement to what we do every day to bring facts and the truth to the American people and our viewers and readers around the world.”

Greg McCaffery, the chair of NLP’s board, welcomed her to the organization. “Abby Phillip’s commitment to NLP’s goals and mission is clear. We are thrilled to have her join the board.”

Phillip established her initial connection to NLP in 2016 when she was a reporter at The Washington Post. She participated in a “virtual visit” event along with Matea Gold, who is now the Post’s national political enterprise and investigations editor and a member of NLP’s National Leadership Council.

Deep experience covering politics, other major stories

Based in D.C., she left the Post for CNN in 2017 to cover the Trump administration and served as White House correspondent through 2019. In January 2020, she moderated the CNN Democratic presidential debate in Iowa. She also anchored special coverage of “Election Night in America” for the 2020 election — coverage that lasted for several days until CNN was the first news outlet to project Joe Biden as the winner.

While at the Post, Phillip was a national political reporter. She covered the White House and wrote about a wide range of subjects related to the Trump administration. As a campaign reporter during the 2016 election, she covered Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign and was also a general assignment reporter, covering domestic and international news — including the mass shootings in Charleston, South Carolina, and San Bernardino, California.

Before joining the paper, Phillip was a digital reporter for politics at ABC News. She also covered the Obama White House for POLITICO as well as campaign finance and lobbying.

A graduate of Harvard University, Phillip is working on her first book, THE DREAM DEFERRED: Jesse Jackson, Black Political Power, and the Year that Changed America, which will be released in 2022. It will be the first major contemporary book on the life and political legacy of Jackson, focusing on his groundbreaking run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1988.

News literacy ambassador brings ‘seasoned’ approach to education

An award-winning history teacher at the Gordon Parks School for Inquisitive Minds in Queens, New York, and a news literacy ambassador for NLP, Street is committed to elevating her students’ learning experience through her “seasoned” approach.

“I remember many years ago, I bought a wok and was washing it out. My brother said, ‘Don’t wash it with soap and water, just wipe it out so that every time you cook, it seasons the food,’” she recalls. “When you add a little heat to something, you bring a whole lot of different flavors.”

This cooking metaphor, she believes, applies to teaching.

Street, who became an educator after working on Wall Street, harvests the flavors from a diversity of experiences and opportunities that she brings to the classroom. Here are just a few examples. She is a member of the New York State Council for the Social Studies Supervisory Committee and completed New York City’s Leaders in Education Apprentice Program. She studied the African diaspora at New York University and attended the Tufts in London program. Also, she earned a certificate in education leadership and administration from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education.

News literacy ambassador, teacher

This ever-curious and engaged approach to learning and life led her to make news literacy education an imperative. “I have been teaching it because I’m compelled to do so. Because we’re living it,” says Street. This year, because of COVID-19 restrictions, she teaches history remotely to 74 eighth-graders.

NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom is a main ingredient in this instruction. “When I went into Checkology, I just wanted to stay in there all day,” Street says. She considers the guidance to stop and weigh information before believing, sharing or taking action a fundamental lesson. “I use that in the classroom. I’ll say, ‘Let’s pause. Before you make a decision, make sure you are well informed.’”

Relying on events both current and historical, she encourages students to make their own realizations about the information they encounter. She reminds them, “I’m not here to tell you what to think; it’s my goal to get you to think.”

A mom herself, Street brings a maternal concern to the classroom. “What I want for my children, I want for other children: Access and exposure to information where they can find their truth,” she says.

As an NLP ambassador, Street advocates for news literacy education and support educators who join NLP’s News Literacy Educator Network — NewsLit Nation. This role gives her a new and important way to bring a little extra seasoning to the education system, and to her life.

Black History Month: Pioneering journalists, media

This February, during Black History Month, we’re shining a light on pioneering Black journalists and news media from the past two centuries. Many of these reporters and outlets overcame incredible obstacles and discriminatory systemic structures to report the facts in their communities. Many are also relatively unknown to the news-consuming public. We hope to help change that. Follow our Twitter thread throughout February as we highlight a journalist and/or news outlet each weekday.

We began by highlighting the Freedom’s Journal, the first Black-owned and -operated newspaper in the United States. The four-page, four-column paper debuted in 1827, the same year that slavery was abolished in New York State. Like many of the publications operated by or created for Black Americans that would follow, Freedom’s Journal served to counter racist commentary published in the mainstream press.

Twenty years later, Frederick Douglass and Martin Delaney launched The North Star. The abolitionist newspaper would become the most influential anti-slavery publication of the 19th century, focusing on anti-slavery progress, women’s rights and Black empowerment. The North Star published 565 issues between 1847 and 1851, according to the Library of Congress. In the late 1800s, Black investigative journalism rose to the forefront as Ida B. Wells exposed the widespread practice of lynching, particularly of Black men. Wells’ work is featured in our Checkology® lesson “Democracy’s Watchdog.”

Still publishing today

The 1900s saw the creation of more Black-owned newspapers, including two of the most respected publications that still publish today. Robert Sengstacke Abbott founded The Chicago Defender in 1905, and shepherded its growth into a local paper with a weekly circulation of 16,000 in its first decade. James H. Anderson put out the first edition of the Amsterdam News, a New York paper, on Dec. 4, 1909, with six sheets of paper and a $10 investment. The publication grew quickly to cover not just local stories but national news as well. A year later, in 1910, W.E.B. Du Bois served as the editor of the NAACP’s first issue of The Crisis, its official magazine. It took off from there.

Continuing chronologically through the 1900s, we’re highlighting just some of the many Black journalists that made indelible impacts with their reporting. From Charlotta A. Bass to Ted Poston and on and on, follow our Twitter thread for more throughout February.

New education secretary must prioritize civics education

Strengthening our democracy by transforming civics education

One of the primary purposes of public education is to teach the next generation about the functioning of a democratic society — and to foster its engagement as equal and engaged participants who will seek to preserve and improve democratic norms and practices. But those who lead by falsehoods represent a threat to our democracy, in part because many people lack an understanding of how our system of government works and how they can become informed about it. If we fail to teach civics, our young people — tomorrow’s voters — will be at a great disadvantage. And the fewer people who can engage in rational, fact-based debate, the greater the chance that we will be unable to govern ourselves, jeopardizing the future of our democratic way of life.

We can commit to resolve this problem by making civics the centerpiece of a quality education. An effective civics curriculum must include news literacy at its core to help young people develop critical thinking skills to discern fact from fiction and determine the credibility of the news and other content that bombards them daily. News literacy gives people the ability to become smart, active and engaged consumers of news and information and empowers them to participate in the civic life of their communities and country.

We understand the many challenges that Secretary of Education nominee Cardona faces in overcoming the unprecedented obstacles imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, but this moment is too important to let civics fall by the wayside. As President Biden said in his inaugural address, “We must reject the culture where facts themselves are manipulated and even manufactured.” Cardona can take the lead on this by recommitting the country and our education system to a civics education that has news literacy has a key component.

NLP launches NewsLit Nation, the News Literacy Educator Network

Nationwide community of teachers, librarians and administrators advocate news literacy education

With educators on the frontline of the fight against misinformation, NewsLit Nation provides resources and know-how for this urgent and important work. The network also organizes locally to enable educators to push for news literacy instruction in their schools and communities, says Ebonee Rice, NLP’s vice president of the educator network.

“We’re building an army of news literacy educators to mobilize their peers and create a future founded on facts,” she says. “We’re here to empower educators with the tools they need to actively teach students the abilities to become equal and engaged participants in our democracy.’’

What is NewsLit Nation?

NewsLit Nation:

- Trains teachers, librarians and school administrators across the country to advocate on behalf of a news literacy curriculum.

- Helps you find opportunities for local partnerships and build channels of communication for your communities as local news literacy champions.

- Gives you access to exclusive professional development opportunities, webinars, other training and additional support through online forums and message boards.

- Acts as the resource library for all our news literacy materials for educators.

And, NewsLit Nation includes a network of ambassadors — educators working to create a sense of community in their local and regional school districts. (Thirteen news literacy ambassadors are already working in 10 cities across the country.)

Educators can easily join the network by registering here.

NewsLit Week | Wisconsin students win PSA contest

Students in Lisa Ruehlow’s Media Literacy class at Amery High School in Wisconsin combined creativity and their Checkology® lessons to create public service announcements about the importance of news literacy for young people. And two of them took top honors for the national PSA contest sponsored by the News Literacy Project (NLP) and The E.W. Scripps Company. The new contest was part of National News Literacy Week (Jan. 25-29.) One of Ruehlow’s students won first prize, and another was selected as runner-up.

The winners are:

First prize: Nicholas Hahn, senior

His video featured clips from current events to demonstrate the real — and often harmful — impacts of misinformation. Watch Nicholas’ PSA.

Runner-up: Mary Mallum, senior

She used animated graphics to provide tips for parsing the false from the factual. Watch Mary’s PSA.

NLP and Scripps, sponsors of National News Literacy Week, asked students taking Checkology virtual classroom lessons to submit a 30-second video PSA related to the week’s theme: Get NewsLit fit. The PSA contest aimed to encourage young people to promote news literacy to their peers.

The winning students took a new course that Ruehlow created and taught for the first time last fall. The class of 20 included mostly seniors, plus a few juniors and sophomores. All completed the PSA assignment for class. Throughout the semester the students enthusiastically embraced the topic of news literacy, Ruehlow says.

“I am exceedingly happy that students see the value of the tools they have learned — they are sharing their insights with others, and are quite passionate about it,” she says. “Many have told me that they think this class should be required of every high school student since this topic is so incredibly important to their daily lives.”

The importance of media literacy

When she asked students why they thought media literacy was important, they offered thoughtful responses.

- “Media Literacy is more critical than ever as people spend so much time on social media, where anyone can post something and claim it as ‘news.’”

- “It’s important to know what’s true and how to verify or debunk it for ourselves. With people spending so much time-consuming media, it can help our relationships, our country, and our digital communities by knowing what’s real and not allowing it to evoke such a severe emotional response.”

- “Media literacy is important because being misled by false information can result in harmful or incomplete understandings. That can result in action being taken, such as storming the Capitol.”

Her students clearly grasp the significance and urgency of becoming more news-literate. Ruehlow — and other educators like her — who are dedicated to this work — make that possible.

NewsLit Week | Use ‘PEP’ to talk to conspiracy believers

In Texas, an air conditioning repairman is run off the road and assaulted by a former police captain trying to find forged presidential election ballots. Closer to home, you learn your cousin is convinced of widespread voter fraud. A suicide bomber detonates a massive explosion in downtown Nashville, possibly targeting the AT&T building over 5G technology paranoia.

Meanwhile, your college roommate frequently posts about 5G causing coronavirus. A Wisconsin pharmacist is accused of deliberately ruining doses of the COVID-19 vaccine because he believed it would alter human DNA; your spouse is worried the vaccine contains a microchip.

Conspiratorial beliefs are seemingly everywhere, and they’re being shared by friends, family and loved ones.

Talking to conspiracy believers

You might be struggling with how to talk to these otherwise rational people about obviously irrational beliefs — and you’re not alone. According to the Pew Research Center, 71% of U.S. adults have heard one or more conspiracy theories about the coronavirus outbreak and 25% see at least some truth in them. You may feel like there’s nothing you can say or do to persuade friends or family from beliefs like these that are thoroughly and credibly proven false. You might feel too discouraged to even try, but you’re not powerless to confront this.

Addressing a person with entrenched false beliefs requires what I call an ongoing “PEP” talk – an approach based on patience, empathy and persistence. It’s more than just one difficult conversation. You’ll need to understand the feelings and emotions that motivate people to dive deeper into these false narratives. You’ll have to recognize that these are genuine beliefs that “feel” true to the people who share them. Do not criticize or attack. This causes a “backfire effect,” making the person reject contradictory information and hold tighter to anything that reinforces their belief. You need a base level of respect and a genuine desire to commit to a shared set of facts to succeed.

Start with patience, then empathy

The person you care about did not develop these beliefs overnight. Your friend or relative may have joined an online community of believers and soon become immersed in their echo chamber. You must listen to how and why they formed their beliefs and understand the sources of their information. This can be frustrating. Take a deep breath and pause before getting angry and shutting down any conversation.

Confronting someone to tell them they may be wrong about something they firmly believe in is uncomfortable – for both sides involved. That’s why empathy is so important. Respect that this person genuinely believes their thinking is accurate and recognize how they arrived at it. Many had fears and anxieties that they sought to alleviate, leading them to these new beliefs. This likely led to conflicting and contradictory ideas and cognitive dissonance, a form of psychological and emotional stress created by those conflicted feelings. They engaged in motivated reasoning, or the active searching for any and all information that reinforces the belief and eases the stress. The belief was reinforced in their new community and eventually became part of their identity, making it significantly more difficult to dissuade them. Understanding this will help you to be empathetic about their feelings.

Be persistent

Finally, use persistence. Regularly share new, verified information in a way that encourages the person to evaluate that information for themselves and to begin questioning their existing beliefs. Ask them, politely, to read new articles, consider new sources and tell you what they think. Express your feelings about their sources as skepticism, not outright rejection, and ask them to explain how and why they trust them. Using their criteria for a trustworthy source, share more reputable sources that might meet them and discuss why you trust them. Make this a dialogue, focusing on sharing ideas, beliefs and information.

Resolve to not give up on your friend or relative. Consider including other friends or loved ones who share your approach. The News Literacy Project has created a new Checkology® lesson to help people understand how conspiratorial thinking works; be sure to share it. Try to keep an the conversation going, without pestering. The goal is to ensure that your friend or relative gradually will accept your guidance and recognize your effort is out of love, respect and friendship, not derision and mockery.

Many of us are dealing with deep rifts among friends, family and loved ones, which are only likely to expand with persistent conspiracy theories, like recent false claims about COVID-19 vaccines. We can stop this from tearing us apart, if we devote the effort to trying. That’s at least one thing we can all agree on.

NewsLit Week | Seventh-graders connect dangers of misinformation to daily lives

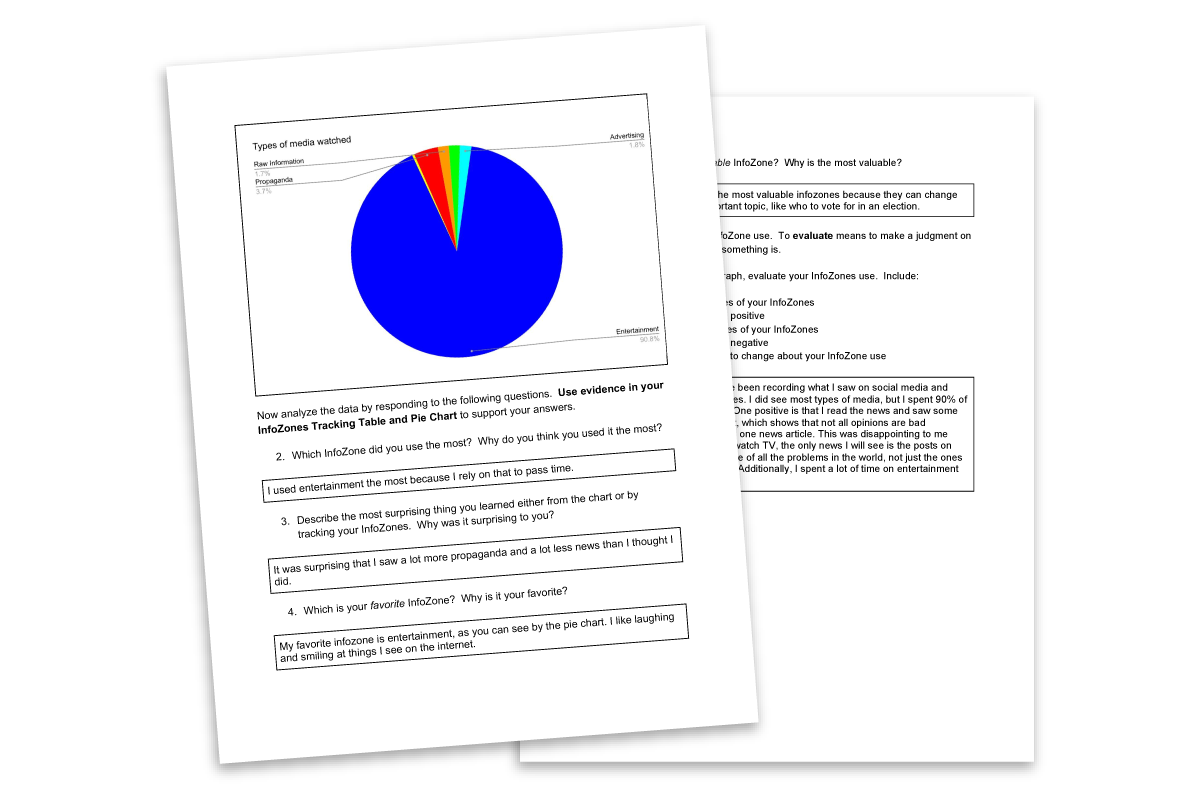

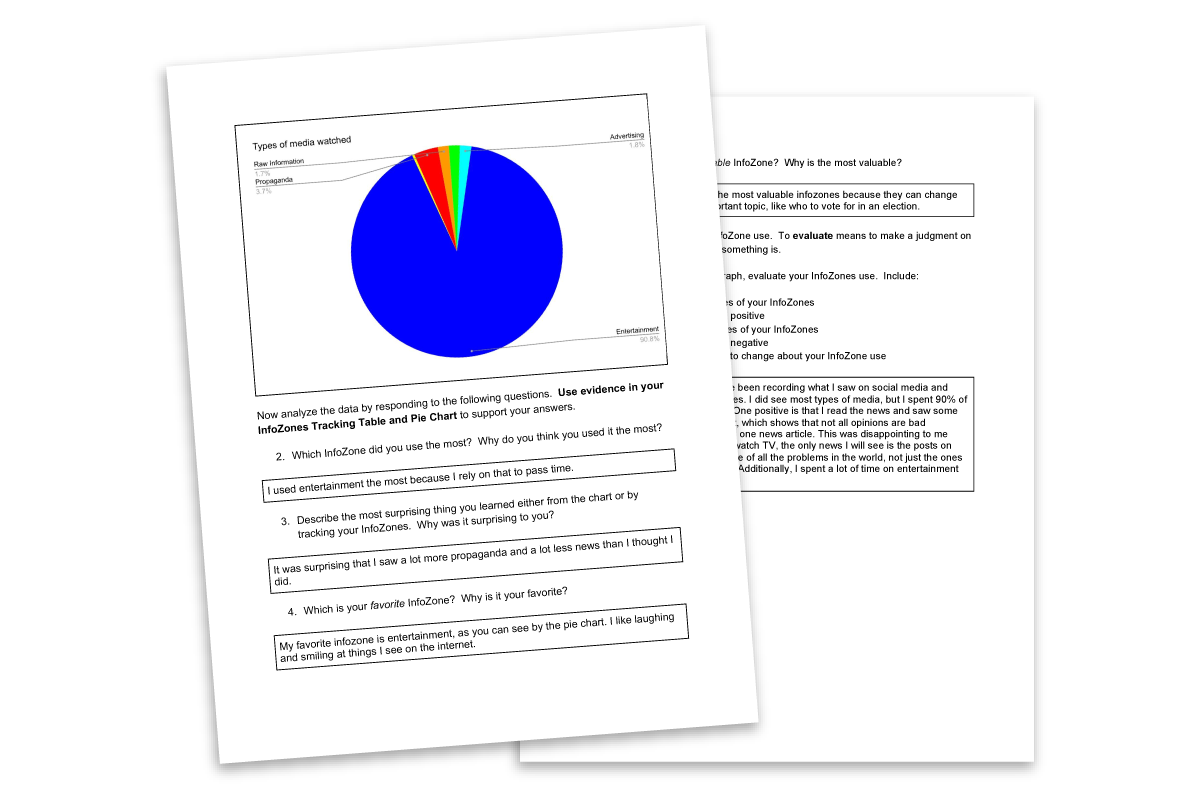

A student’s poster depicting the information ecosystem as the solar system using InfoZone categories.

During a news literacy unit, seventh-graders in Jeff Rosen’s history class learned about different categories of information and the dangers of misinformation. They also learned about themselves and their place in the information ecosystem.

“They began to identify some of the harmful things they were seeing,” says Rosen, a social studies teacher at The Joseph Sears School in Kenilworth, Illinois. “I don’t think the kids knew they were being exposed to misinformation.”

An educator for 14 years, Rosen led his history class through a two-week unit on media literacy using NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom. He focused on the “InfoZones” and “Misinformation” lessons and COVID-19 misinformation resources. But the learning didn’t end there.

“I try to find ways for the kids to apply the skills they learn to their everyday lives through tracking documents and reflection,” he says. “There’s a really urgent need to learn this now. They’re consuming information every day from a variety of sources and are not equipped with skills to differentiate what they are seeing.”

Measuring behavior

To accomplish this, students connected what they learned to their own lives by tracking information they consumed over two days. They categorized content by primary purpose — news, opinion, entertainment, advertising, raw information and propaganda/misinformation. Students then illustrated their findings in pie charts and reflected on what they found.

Examples of student work tracking their media consumption and reflecting on their habits.

Here is one student’s honest insight.

“I spent 90% of my time watching entertainment. One positive is that I read the news and saw some respectful opinions on the internet, which shows that not all opinions are bad propaganda. However, I only read one news article. This was disappointing to me because if I don’t read articles or watch TV, the only news I will see is the posts on Instagram. I want to be more aware of all the problems in the world, not just the ones that make it onto people’s stories.”

Recognizing dangers of misinformation

The students also discovered that so-called “fake news” is actually part of the information they see and engage with every day, underscoring the dangers of misinformation.

To reinforce this, Rosen had his class delve deeper by creating posters that describe a system with symbols for the “InfoZones” categories. They then demonstrated how misinformation poses a threat to a healthy system. One student represented misinformation as an asteroid in the solar system. Another labeled misinformation as pollution in a marine ecosystem.

“This shows that the kids have a deep understanding of these kinds of information. Applying symbols to them requires abstract thinking,” Rosen says. “It’s not just a surface skill they’re learning. They’re starting to internalize it and put it into practice.”

Rosen has also learned a good deal over the four years that he has been teaching Checkology. Originally, students simply enjoyed Checkology’s use of examples they could relate to — familiar YouTube stars or advertisements for favorite products.

“Now kids really recognize the importance of being able to identify what they’re seeing, and it’s an important skill to them. I’ve seen a change in their attitudes toward the media. Kids recognize the importance and urgency of being able to do this,” he says.

And that urgency and importance are never going away, Rosen notes. “We’re never going back. We’re never going to be able to say ‘don’t use these platforms.’ There’s so much good information out there but so much that’s bad. We need to teach them how to navigate it.”

With his creative approach, Rosen is doing just that.

Delivering news literacy to journalism students, remotely

When the Houston Independent School District started the 2020-21 school year with 100% remote learning, journalism educator David Fanucchi needed to find an engaging way to teach news literacy to his students at Margaret Long Wisdom High School.

A colleague at Houston’s Bellaire High School, Andrea Negri, suggested NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom. The browser based, e-learning platform with interactive lessons that students can do independently was exactly what Fanucchi was looking for.

“I thought Checkology provided a fantastic way for students to complete some relevant online lessons about journalism at a time when it is so difficult to keep their attention remotely,” Fanucchi says. “Teachers are struggling to find tools like that to use, and I was just so excited that these easy-to-understand modules were created and that I could use them in my classes.”

He assigned all seven of his classes the Checkology 101 course, which explores essential news literacy topics through the lessons “InfoZones,” “The First Amendment,” “Democracy’s Watchdog,” “Practicing Quality Journalism,” “Understanding Bias” and “Misinformation.” The course also includes related activities, such as source detection and evidence evaluation “missions” to reinforce the lessons.

“We went through them all in about three weeks (a total of six or seven class periods that each lasts about 90 minutes),” Fanucchi explains. “This was all done virtually on their own laptops.”

A deepened understanding

Dulce Macha, a sophomore in one of Fanucchi’s journalism classes, had a basic understanding of news literacy before she began using Checkology. “What I had known about news literacy was that it helps you judge the reliability and credibility of information given,” she says.

But the lessons deepened her knowledge. “The most surprising thing that I learned during the course was that there are many steps that go into a journalist’s work, such as checking for credibility and staying away from bias,” Macha says.

Fanucchi found the “Practicing Quality Journalism” lesson particularly valuable to his student journalists. “It taught them a real-life scenario of being a news reporter and covering the scene of a car crash. I think it did a phenomenal job of giving the students a real feeling of what a journalist does to ensure accuracy in his/her reporting,” he says.

Macha enjoyed that assignment and how Checkology enabled her to illustrate what she learned in different ways. “What I liked about the lessons was that they had areas where we had to choose the right answer and also areas where we had to be in the journalist’s shoes, and write our opinions on it,” she says.

‘Extremely important during these times’

Fanucchi says students need help understanding how credible journalism works and identifying reliable sources and fact-based information. “It is extremely important during these times of so much chaos in the news business. Students are having a harder time every day figuring out what the truth is,” he says.

Since studying news literacy, Macha is having an easier time doing just that. “It has changed the way I consume the news and judge content and sources. This course has given me a way of judging the credibility of the news that I read and judging whether it could be fake or not,” she says.

Macha has not yet needed to help friends or family members avoid being fooled by misinformation, but she is prepared to do so. “If there was a point where something like that happened, I would certainly help them out and talk to them about the ways they should judge the credibility and reliability of the information given,” she says.

Making civics relevant through news literacy

Scott Zwierzchowski teaches civics to students in grades 11 and 12 at Lincoln Park High School in Chicago. In September 2020, he and his colleagues implemented a short news literacy unit. Their goal is to prepare students to evaluate sources and sort fact from fiction throughout the year. NLP recently checked in with Scott to learn more about how he incorporates news literacy into his courses. Teaching is taking place in a fully remote learning environment due to the COVID-19 public health crisis.

NLP: Why did you decide to use Checkology®?

SZ: [My colleagues and I] had a conversation about the continual need to connect civics and government topics to modern day issues and debates/discussions, and thus a need for quality news literacy. After finding more out about Checkology, I was really psyched about it. Looking at how interactive Checkology was, and how it was really tailored to ease of use and quality engagement tools, we knew it would be helpful for us. In addition, the option to bring in a vetted, professional journalist into the classroom was a very intriguing option — although we ultimately did not do it for time constraints, I think we would pursue it in the future..

NLP: How did it fit in with your civics/law focus?

SZ: We try to start out the year with a unit on news literacy. Our plan has been to introduce topics of news literacy and continually refer back to them throughout each unit of study, but that is a continual process of development. My colleagues and I are working on ways, for example, for students to use the summative assignment they make throughout the year to evaluate sources they find online.

NLP: What did fully remote implementation of Checkology look like?

SZ: It looked different on different days! On some days, we would introduce the topic synchronously in our Google Meet, for about 10 to 15 minutes, then let the students loose to do the lesson on their own, and I would give feedback to the students as they completed it. On one day, we did it together by me projecting the lesson and them answering the questions on their own devices. That worked decently well, as they were already a bit familiar with that format through PearDeck.

NLP: What did students think about using the platform?

SZ: Students reported really liking the asynchronous aspect. They also reported really liking the format — they said it was easy to navigate, easy to answer questions, and was super simple to provide their ideas. They thought it was clear, and mentioned that they learned from it, and also mentioned that it wasn’t too hard, or too easy.

NLP: What kind of impact have the lessons had on your civics students?

SZ: I think our teachers on the team have seen some great improvements! As we dive into our elections unit, the students are demonstrating skills of being keenly aware of the author of the source, biases of sources, and have pointed out even logical fallacies of their peers, other teachers, and administrators.

NLP: Do you plan on using Checkology in the future?

SZ: We DEFINITELY plan on using it in the future. I’ve been recommending it to colleagues who teach the AP Government and Politics course, and others throughout our school, and how beneficial it is. Ultimately, I’d love to create more plans to bring a full, longer unit into fruition.

Check out this civics news literacy unit

Checkology teachers: assign Scott’s course to your class. Click here for instructions.

Essential question

What does it look like to be an educated information consumer?

Objectives

Students will be able to achieve mastery in the following unit content topics and skills.

Topics

- Defining news

- Media bias

- Language in news

- Commentary vs. news

Skills

- Identify news source information

- Analyze news sources for purpose and content

- Evaluate news sources for bias and logical fallacies

Unit plan

Day 1: What is News?

What factors determine the newsworthiness of a story? Students learned about Checkology’s “Big Four” factors in the lesson “What is News.” They are the extent to which something is timely, interesting, important and unique.

Day 2: Understanding Bias

Students completed the Checkology lesson. Then, they examined three news stories in groups and analyzed the types and forms of bias that they may have detected in the stories.

Days 3 and 4: The Power of Language with Checkology’s “Arguments and Evidence” lesson

On day 3, students completed “Arguments and Evidence” asynchronously. Then, together in class on day 4, students debriefed on the lesson and further practiced together remotely using the “Spot the Logical Fallacy” exercise from Checkology.

Day 5: Fact-checking in the digital age

Students supplemented Scott’s fact-checking lesson with the Checkology fact-checking mission “Verifying social media content” with David Clinch from Storyful.

- Note: The class went through Hurricane Sandy photos [in this slide deck] and discussed “How might people who are trying to get information about the hurricane have been influenced by the images?” Discussing how altered images and unconfirmed sources affect one’s perception of the world helped us ground some of our initial ideas on verifying online content. Discussing the Truman photo and its impact helped us further discuss why verifying information in all forms of news media is important (which we’ll definitely be talking about in class this week post-election). We had used this fact-checking in the digital age handout, but found that many students have used this site before in their computer science classes. Therefore we went with the Checkology lesson. Students said the lesson made the task easy to accomplish and helped them better understand the steps for fact-checking. The Checkology lesson also provided them with a more realistic example of what they would see every day, versus examples concocted for classroom purposes.

Days 6 and 7: End-of-unit project

Students created a process to help them determine the credibility of a news source. This process is meant to be used throughout the year when studying other topics and referencing news sources. View the assignment and a template You can also use Checkology’s Quick Check widget in the Check Center to help guide students through the process of determining the credibility of a claim or a source.

NLP offers new, urgently needed lesson on conspiratorial thinking

As recent events have demonstrated, false conspiracy theories online can fuel dangerous actions in real life. In this context, NLP is introducing a new lesson to educate students and the public about how conspiratorial thinking develops and its effects.

The comprehensive “Conspiratorial Thinking” lesson, included with NLP’s free Checkology® e-learning platform, seeks to help people understand the factors that allow conspiratorial thinking to take hold and conspiracy theories to flourish. It is available to educators and the general public.

You can preview the lesson here. For the best experience, register here to explore this and all Checkology lessons.

“The need to educate about conspiracy theories and why people believe them cannot be understated,” said John Silva, NLP’s senior director of education and training. “This is why we developed a lesson to teach young people about conspiratorial thinking and how it leads to a breakdown of critical, rational thought and belief becoming more important than facts. We must address the warning signs of cognitive dissonance and motivated reasoning — the thought processes that make us seek any information to support a belief.”

Renée DiResta, research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory who investigates the spread of false narratives across social networks and assists policymakers in understanding and responding to them, hosts the lesson.

The new lesson teaches people to understand key components of conspiratorial thinking, including:

- What a conspiracy theory is and what separates it from other kinds of misinformation.

- How it can be captivating despite a lack of evidence to support it.

- The real-world consequences and the political and social impact of conspiracy theories.

“More importantly, added Silva, “people will learn how to recognize forms of cognitive biases that make false information seem true and how to evaluate sources and accept information as true only if it is verifiable and credible.”

“Conspiratorial Thinking” is the 14th lesson in NLP’s browser-based platform, which teaches students how to navigate the digital landscape by developing news literacy knowledge, skills and habits of mind.

NewsLit Week | NLP, Scripps team up for National News Literacy Week 2021

This second annual National News Literacy Week (Jan. 25-29) aims to promote news literacy as a fundamental life skill and to provide the public with the tools needed to be an informed and empowered populace.

The public service announcement, an animated video that challenges people to test their “news literacy fitness” and to resolve to be healthier news consumers, will run in both Spanish and English across Scripps’ social, digital and broadcast channels including its 60 local broadcast television stations; national networks Newsy, Court TV, Bounce, Laff, Grit and Court TV Mystery; and promotions from the Scripps National Spelling Bee, Simplemost and Triton Digital.

Media partners large and small are offering pro bono ad space to further amplify the campaign’s message: The Associated Press, BuzzFeed News, the Los Angeles Times, NPR, The New Yorker, The New York Times, Pro Publica, Vox Media, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and members of the Local Media Association and Local Media Consortium are among the organizations committing space to the effort.

Engagement with students, educators, public

The News Literacy Project (NLP) will engage educators, students and the public throughout the week with quizzes, tips and tools featured through its social media channels and on the NewsLiteracyWeek.org landing page. A national professional development event, NewsLitCamp®, will be held on Jan. 26 in partnership with CNN, as well as a #NewsLiteracyWeek Twitter chat on Jan. 25 at 3 p.m. ET and an edWeb session on conspiratorial thinking with NLP’s education team on Jan. 27 at 4 p.m. ET. NLP will also formally launch its NewsLit Nation educator network, which will support local ambassadors advocating for news literacy to be taught in their local schools.

Consequences for democracy

“In today’s complex information and media ecosystem, the proliferation of rumors, lies and the deliberate spread of misinformation has devastating consequences for our democracy,” said Scripps President and CEO Adam Symson. “At the same time, it’s harder than ever to distinguish verified facts and objective journalism from opinion, propaganda and even total fiction. It is our urgent responsibility – as friends, coworkers, teachers, parents and fellow citizens – to equip ourselves and younger generations with the tools necessary to discern truth from misinformation. With our partners at the News Literacy Project, Scripps is committed to bringing discussions about what it means to be news-literate into newsrooms, classrooms and living rooms across the country to empower the public to be stronger news consumers.”

“The corrosive threat of misinformation now permeates every aspect of our civic life,” said Alan C. Miller, founder and CEO of the News Literacy Project. “We’ve seen it surge in the past year around the global pandemic, racial justice protests and during the presidential election. As the violent assault on the U.S. Capitol demonstrated, this contagion of viral rumors and conspiracy theories can have deadly consequences. It’s time to confront this rising tide that threatens our democracy. Together, we must take personal responsibility for the news and other information we consume and share to assure a future founded on facts.”

During National News Literacy Week 2021, Scripps’ news teams will premiere stories related to the topic of news literacy on-air and online across Scripps’ platforms, with a selection available at the campaign landing page, NewsLiteracyWeek.org.

National News Literacy Week 2021: How to get involved

The public can get involved with National News Literacy Week, Jan. 25-29, in a number of ways:

- Visit NewsLiteracyWeek.org to test your “news literacy fitness” and take the pledge to be news-literate.

- Watch NLP’s new Checkology® virtual classroom lesson “Conspiratorial Thinking” to learn how and why conspiracy theories develop and how to prevent people from falling for them.

- Join the conversation on social media at #NewsLiteracyWeek.

National News Literacy Week is part of an ongoing partnership between Scripps and NLP to advance awareness of news literacy.

Our statement on the assault on the Capitol

We deplore the violent assault on the U.S. Capitol today by a lawless mob. While we support the right to peaceful assembly and free speech guaranteed by the First Amendment, this was an anti-democratic attempt to prevent the culmination of a free and fair election.

The attack on the Congress — and the post-election events leading up to it — underscore the need for robust civics education that gives people a basic understanding of the Constitution and the fundamental principles of democracy. We call on the new Congress to appropriate funds now to achieve this goal and to protect our democracy. This must include funding for news literacy, which empowers people to discern credible information from misinformation and gives them the tools to be equal, informed and engaged participants in the country’s civic life.

Such an education is essential to bridging the deep partisan divide and alternative realities that have driven our democracy to such a dangerous place.

NLP launches News Literacy Ambassador Program

If 2020 has made anything clear, it’s that the future of our democracy depends on our collective ability to sort fact from fiction — and teaching students news literacy skills is crucial to this. To build our local footprint through community organizing efforts in the fight against misinformation, we have launched a News Literacy Ambassador Program.

Through this regional model for news literacy education, we can create a sense of belonging and community among educators. We know that if this movement is to be successful, it must be inclusive and local. These paid local organizers serve as our thought leadership partners, helping to identify the unique needs of educators in their school districts. These efforts will further help to combat misinformation and create a more news-literate generation of news consumers.

Thanks to news literacy leaders like you we have been able to make significant achievements during this challenging year. With our News Literacy Ambassador Program, we can do even more.

We welcome the following group of ambassadors:

Annual report: NLP meets challenges, expands mission

This week, we're releasing our annual report for fiscal year 2020 (July 2019-June 2020). It presents results of our work as we expanded our mission to reach not just students and educators but also the public. It also covers a time of great challenges for all of us. We believe that it reflects significant progress during the past year, and great promise for the future.

By Greg McCaffery and Alan C. Miller

Our world has been shaken and transformed since we shared our first annual report with you. In fact, it often feels like last fall was a decade ago.

We’re proud to say that NLP has responded to the myriad challenges wrought by COVID-19 with resourcefulness and determination. As a result, with the second year of our four-year strategic plan completed, we marked numerous important gains.

During the 2019-20 school year we brought news literacy education to 702 educators and 33,894 students through our Checkology® virtual classroom. The student assessments conducted at the end of the school year prove that Checkology works. Far more students were able to recognize the standards of quality journalism and to understand the watchdog role of a free press and the First Amendment in a democracy.

The pandemic and the accompanying “infodemic” — an overabundance of information, including misinformation — inspired us to step up in new and innovative ways.

A rapid, robust response

In March, in response to schools nationwide transitioning to remote teaching, we decided to provide Checkology at no cost to educators and parents engaged in distance learning or homeschooling. In addition, we created a special page on our website with reliable information about COVID-19, used our weekly newsletter The Sift® to debunk misinformation about the virus, and developed two educational webinar series that drew 1,768 participants.

We knew we had to invest in additional resources to provide a growing number of educators with the support they needed to teach news literacy. We created an educator outreach and success team to respond to our educators and to help them succeed, providing support to implement Checkology and promoting the platform to school districts. And we also brought Ebonee Rice, a community engagement expert, on board to create and mobilize a nationwide network of 20,000 educators committed to news literacy.

Amid a perfect storm of misinformation and disinformation from the pandemic, the protests for racial justice and the 2020 elections, we moved to expand our mission to include you. Our free resources are now available to meet the urgent need for news literacy among people of all ages, and to help everyone become savvier consumers of news and information.

We hope that as you read this annual report, including a special section on the start of this new fiscal year, you will recognize your contributions in making these accomplishments possible.

Thank you for your ongoing support and for helping to preserve a future founded on facts.

From the Sift®: Understanding misinformation in the wake of the election

Misinformation and conspiracy theories thrive when curiosity and controversy are widespread and conclusive information is scarce or unavailable. The deeply polarized 2020 presidential election not only produced these conditions, it sustained them as ballots in a number of swing states with narrow vote margins were adjudicated and carefully counted.

To be sure, viral rumors swirled in the aftermath of Election Day. People who had been primed by partisan rhetoric to expect voter fraud leaned into their own biases. They misinterpreted isolated moments on livestreams of the ballot counting process in counties in several swing states, mistakenly saw “evidence” of rogue ballots being delivered in vague video clips, and were exploited by bad actors who readily circulated staged, manipulated and out-of-context content designed to mislead.

But the impact of these falsehoods was blunted by the work of professional fact-checkers, disinformation researchers and standards-based news organizations — and by social media platforms, which improved their content moderation efforts for the election. Facebook and Twitter took more effective actions against misinformation than either had previously. (However, Twitter indicated that with the election over, it would stop using warning labels on false or misleading tweets about the election outcome but continue its use of labels that provide additional context.) YouTube was more lax, allowing videos containing false claims about the election — including those that it acknowledged undermine trust in the democratic process — to remain live but without ads.

The days of uncertainty sparked isolated protests and some arrests, including two armed Virginia men. But for all the unresolved questions and still-rampant falsehoods, it seems, at least so far, that the worst-case scenarios were averted, even in an otherwise historic election with record turnout.

Related:

- “Here’s A Running List Of False And Misleading Information About The Election” (Jane Lytvynenko and Craig Silverman, BuzzFeed News).