Classroom Connection: COVID-19 conspiracy theory outbreak

A baseless conspiracy theory about the COVID-19 pandemic migrated from fringe internet communities into more mainstream conversations last week, spreading dangerous doubt about the seriousness of the pandemic across the United States and around the world.

A baseless conspiracy theory about the COVID-19 pandemic migrated from fringe internet communities into more mainstream conversations last week, spreading dangerous doubt about the seriousness of the pandemic across the United States and around the world.

The theory — that the pandemic is a staged hoax or “false flag” event — had emerged among anti-vaccination and QAnon communities online by mid-March. But the idea was galvanized on social media following a powerful March 25 New York Times report featuring video of Colleen Smith, an emergency room doctor at Elmhurst Hospital in Queens. She provided a firsthand account and video of conditions at the hospital the day before, when 13 people died of COVID-19.

Three days later, Twitter user @22CenturyAssets tweeted: “#filmyourhospital Can this become a thing?” Hours later, the far-right talk radio host Todd Starnes tweeted (archived here) a video of “not much happening” at the Brooklyn Hospital Center — his neighborhood hospital. He said he did so to highlight “what’s really going on out here instead of what the mainstream media is telling you.”

COVID-19 conspiracy spreads

By the following day, more than a dozen photos and videos said to have been shot outside hospitals across the U.S. and around the world had been tweeted with the #FilmYourHospital hashtag. In posts on April 1 and 2, influential QAnon adherents attempted to discredit Smith on Twitter and YouTube. They falsely claimed that she did not actually work at Elmhurst Hospital, They also misinterpreted her background in medical simulation training, and picked apart the video she provided to the Times.

Also fanning the flames of the #FilmYourHospital conspiracy movement was CBS News’ March 30 acknowledgment that it had erroneously used several seconds of footage of a crowded hospital in Italy in a March 25 report (go to 0:45 for the clip) about the impact of COVID-19 on hospitals in New York City. CBS News has offered no further explanation about its mistake.

Safety and privacy issues

Safety and patient privacy concerns largely prevent the press from providing the public with photos and videos from inside hospitals, where the realities of the pandemic are most apparent. That may help explain why this has become such a focal point of conspiracy communities online.

Also note that another widespread conspiracy theory falsely connecting 5G cell towers to the COVID-19 pandemic spiked online last week. It led to a spate of viral rumors — including a variety of false claims that governments are faking the public health crisis to distract the public and push through dangerous new technologies.

Related:

- “What We Pretend to Know About the Coronavirus Could Kill Us” (Charlie Warzel, The New York Times).

- “British 5G towers are being set on fire because of coronavirus conspiracy theories” (Tom Warren, The Verge).

- “YouTube moves to limit spread of false coronavirus 5G theory” (Alex Hern, The Guardian).

- “The latest wildly false COVID-19 conspiracy theory puts the blame on 5G” (Ruth Reader, Fast Company).

- “Here’s why 5G and coronavirus are not connected” (Bob O’Donnell, USA Today).

Discuss: Why are people drawn to conspiracy theories? In what ways could these conspiracy theories about COVID-19 be dangerous? What can we learn from the way the false notion that the pandemic is a hoax went mainstream with the #FilmYourHospital hashtag? How can we work to stop such theories from spreading? Can people be inoculated against conspiratorial thinking? How?

Understanding COVID-19 data: Comparing data across countries

This is the first of a series, presented by our partner SAS, that explores the role of data in understanding the COVID-19 pandemic. SAS is a pioneer in the data management and analytics field. (Check out other posts in the series on our Get Smart About COVID-19 Misinformation page.)

The COVID-19 pandemic has plunged us into a global public health crisis that has experts looking back 100 years for comparison: The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. However, a lot of things have changed since then. While our medical systems are significantly more robust, we are also more connected globally, which allows disease to spread rapidly in new ways. Something else is spreading rapidly as well and marks another huge shift since 1918 – data.

Data is incredibly powerful. It gives us insight into the world around us and can help us quantify what’s happening so we can better understand a situation and make well-informed decisions. In recent years, as number-crunching technology has advanced, data has influenced almost every aspect of our lives: from the activity trackers we wear on our wrists to how social media platforms track our habits online. These developments have helped us verify — or refute — hunches, assumptions and generalizations about important issues based on quantifiable information.

Critical role during pandemic

This is especially critical now as leaders make unprecedented decisions with potentially life and death consequences as we wait, wondering what comes next. At the same time, most of us are not experts at interpreting public health data that describes different components of the crisis — presented through graphs, charts and statistics updated multiple times a day. How can we make the most sense of this data? How can we decide what to believe, what to dismiss and what might be causing unnecessary fear?

At SAS, we work with data every day. While we can’t answer health questions about the pandemic, we can help identify trends we see in COVID-19 data being presented, and point out possible concerns with how it could be interpreted. In this series we will look at three main areas where we ought to pay particularly careful attention: comparing data across countries; comparing data across time; and case fatality rate vs. mortality rate vs. risk of dying. Let’s begin:

Comparing COVID-19 data across countries

As residents of the United States, one piece of information that we might be interested in is how the disease is progressing in other countries, particularly those where infections first occurred and where leaders have implemented similar social distancing recommendations or community restrictions. We can use information from those nations to predict how the disease will progress here, how quickly that will happen, and when we might see light at the end of the tunnel.

But there are some big flaws with looking at these as direct comparisons. While it’s helpful to try to learn lessons from other nations, we must remember that the data doesn’t tell the whole story of what is happening. For example, Italy has the highest case fatality rate of any nation. (The U.S. Centers for Disease Control define case fatality rate as “the proportion of persons with a particular condition (cases) who die from that condition. It is a measure of the severity of the condition.”)

Differing factors

In the case of Italy, we must ask if this is because of the higher proportion of elderly adults in the population? Is it because of an overwhelmed hospital system? Is it a sign that fewer people with mild symptoms are requesting or receiving testing? The answer is probably some combination of those elements.

Here are some factors to consider:

- Nations vary widely in the extent of diagnostic testing being conducted.

- The rate of and criteria for testing greatly impact rates of detection.

- Most testing can tell us only if a person is currently infected and not if that person had been infected and since recovered.

Those are just some of the factors that may contribute to the discrepancies we see in the chart below.

We see a wide variety in the extent of testing among nations, and therefore, the rate of positive tests. Countries with a high rate of positive test results compared to the number of tests conducted are likely requiring stricter testing criteria. Countries with a higher proportion of negative test results are likely instituting more widespread testing practices. As a consequence, they also might detect a higher percentage of actual cases.

One of the big issues in trying to make comparisons of COVID-19 data among nations is that it’s impossible to know, or control, all the factors that go into the numbers reported. When scientists create experiments to thoroughly understand a phenomenon, they carefully control the conditions and influences as much as possible. But the data surrounding the novel coronavirus isn’t coming from careful experiments; it’s coming from the real and messy world where we can’t control or even measure all the factors that go into different national responses or testing practices and where they are changing, with varying frequency.

Other articles in this series:

![]() About SAS: Through innovative analytics software and services, SAS helps customers around the world transform data into intelligence.

About SAS: Through innovative analytics software and services, SAS helps customers around the world transform data into intelligence.

Want to help others avoid COVID-19? Don’t share misinformation!

When a news event or a significant issue grabs hold of the public’s attention, it’s human nature for us to want to get our hands on as much information as we can as fast as we can.

It’s also human nature to act on an impulse to share that information with friends, family and the wider community in an effort to keep people safe from harm. Unfortunately, large breaking news events — especially those connected to controversial, frightening and complex subjects, like the current COVID-19 pandemic — tend to generate a spike in viral rumors.

These stories, anecdotes, ads and memes pass quickly from one person to the next, often with little regard to whether the content is true. Some elements may be accurate, but much is simply a form of digital rumor — half-truths, doctored videos and images, or complete fabrications.

They typically appeal to our emotions, provoking anger, fear, curiosity or hope and overriding our rational minds and critical-thinking skills. When we have an immediate strong response to a piece of content online, our impulse is to take action: to “like” it, to share it immediately, to express whatever we’re feeling about it. Because of that impulse, and because Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and other platforms effortlessly connect us to thousands of people (many of whom we’ve never even met), this content spreads rapidly across social media — even from one platform to another.

So think of these rumors like an actual virus. Mike Baker, a New York Times reporter in Seattle, has been tweeting weekly about the exponential increase in confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States. A “like,” share or retweet of false or unverified content on social media spreads the same way — and the numbers are considerably larger.

Who shares COVID-19 rumors?

Why would someone make up a story or share an unverified rumor? As Craig Silverman noted in Lies, Damn Lies and Viral Content, a 2016 report for Columbia University’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism, behavioral economist Cass Sunstein identified four main types of rumor propagators in his book On Rumors. Here is a quick explanation of what they are and how they apply to the information we see online:

- Those who promote self-interest at the expense of others (for example, people spreading scams and using falsehoods to build up large followings online).

- Those who promote the interests of a group they favor or support (for example, people in one political party who share false claims or misleading videos about a politician in the other party).

- Those motivated by malicious intent (for example, trolls who seek to derail conversations or extremists advancing agendas of hate online).

- Those who act for altruistic reasons (for example, people with a sincere desire to warn others about a possible threat).

In the case of the coronavirus pandemic, we see all of those motivations playing out in our social media feeds. And you might be surprised to discover the biggest misinformation vector in the current crisis: people acting on the altruistic impulse to help others avoid infection — and sharing misinformation without realizing that it’s false or misleading.

Seek credible sources

Whatever the intent, the best way to protect yourself and others from infection with misinformation about COVID-19 or the strain of coronavirus that causes it is to fact-check before you share. There are a number of resources and sites to help you do that. Here are a few:

You can stay ahead of the latest viral rumors — and learn how not to be fooled — by subscribing to our free weekly newsletter, The Sift®; exploring the Get Smart About News section of our website; and downloading our free mobile app, Informable.

Twitter and Facebook act to stem COVID-19 misinformation

In the last week, both Twitter and Facebook have announced additional measures to combat the spread of misinformation about COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2, the strain of coronavirus that causes the disease.

In the last week, both Twitter and Facebook have announced additional measures to combat the spread of misinformation about COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2, the strain of coronavirus that causes the disease.

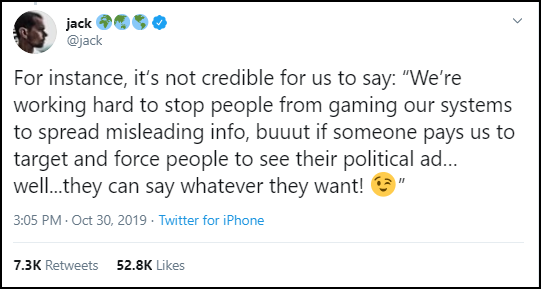

Twitter announced on March 18 that it would remove coronavirus-related content that goes “directly against guidance” from public health and government authorities, such as false and dangerous preventive measures or “cures” and claims that the virus is a hoax designed to harm the economy. Two days later, Twitter Support tweeted that it was working to “verify” the accounts of credible experts in public health. (One critic has urged the company to create a designation for this purpose other than its standard blue checkmark, which signifies only authenticity, not credibility.)

Facebook, WhatsApp

Also on March 18, Facebook, through its subsidiary WhatsApp, announced two initiatives to combat misinformation about COVID-19: a $1 million donation to the Poynter Institute’s International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) and the launch of the WhatsApp Coronavirus Information Hub, where users can find credible health information. (The company also created a similar information center on Facebook.) In addition, WhatsApp is testing new features that enable users to search the internet for additional context about messages that are forwarded to them and is adding localized chatbots (including one run by the World Health Organization) to help guide people to credible information. The platform is also featuring the accounts of 18 IFCN members where users can forward messages for verification.

Joint statement

Joint statement

On March 16, Facebook, Twitter, Google, LinkedIn, Microsoft, Reddit and YouTube issued a joint statement expressing their commitment to “working closely together on COVID-19 response efforts.”

Facebook flagged a number of credible posts about the coronavirus as spam last week, but later explained that this was due to an error in an automated anti-spam system. The company also noted that it was working with a reduced content moderation staff because of COVID-19.

Related coverage

“Facebook has a coronavirus problem. It’s WhatsApp.” (Hadas Gold and Donie O’Sullivan, CNN Business).

“YouTube Is Letting Millions Of People Watch Videos Promoting Misinformation About The Coronavirus” (Joey D’Urso and Alex Wickham, BuzzFeed News).

Classroom Connection: Practicing information hygiene

The parallels between the spread of the new strain of coronavirus and the spread of misinformation and confusion about it — between the actual pandemic and what the World Health Organization calls an “infodemic” — offer a number of important and urgent lessons in news and information literacy. Just as COVID-19 has thrown the weaknesses of our global health infrastructure into stark relief and dramatically raised the stakes of our personal choices and habits, the outbreak has underscored defects in our information infrastructure and is emphasizing the potential impact of our choices and habits online.

‘Information hygiene’

Much of the public health messaging in the last week has focused on the importance of practicing good hygiene and on the need to “flatten the curve” by engaging in “social distancing.” (For example, the #WashYourHands hashtag that trended across social media platforms.) At the same time, we all need to focus on “information hygiene” and flattening the curve of dangerous falsehoods online by taking proactive steps to reduce their spread. Our decisions about which pieces of information to “like” and share can have a surprising impact on others.

For example, a false claim about ways to avoid the virus or cure COVID-19, however well-intentioned, may cause someone to downplay the seriousness of the outbreak or the recommendations of public health officials. Or something posted to social media as a joke might, after being “liked” and shared a number of times, be taken seriously and exacerbate public confusion and panic about the crisis. (Remember, “likes” are also known as “passive sharing,” because many platforms’ algorithms suggest things you “like” to your followers.)

As this crisis unfolds, more and more people will be asked to stay home, meaning that more and more people will be online more than ever before. They will be searching for answers and trying to make sense of the events around them. It is essential that we bring the same seriousness and sense of responsibility to our roles as creators and sharers of information as we do to our roles as conscientious stewards of public health.

For discussion with students

Discussing the COVID-19 pandemic with students is also an opportunity to explore the ways the crisis has ignited a familiar cast of known “bad actors” in the information ecosystem. Hucksters are peddling bogus supplements and miracle cures, some of which are dangerous. Disinformation agents and conspiracy theorists are pushing elaborate falsehoods. Trolls are sowing confusion. Extremists are promoting agendas of hate; and opportunists are using misinformation to generate social media engagement. Hackers are exploiting public fear and uncertainty to compromise accounts and install malware. And millions of ordinary people are inadvertently amplifying misinformation out of well-intentioned attempts to help their friends, family members and followers online.

Social media companies respond

Social media companies are struggling to combat COVID-19 misinformation — partially because many of their systems for policing misinformation were created to address coordinated campaigns, not a global viral misinformation outbreak from ordinary people. (This means monitoring misinformation in dozens of languages and national contexts). Still, they are also taking unprecedented steps in the right direction.

Related reading

- “Pinterest Is Blocking Coronavirus Searches, And People Are Very Happy About It” (Craig Silverman, BuzzFeed News).

- “The WHO and Red Cross rack up big numbers talking coronavirus on TikTok through vastly different strategies” (Harrison Mantas, Poynter).

- “5 quick ways we can all double-check coronavirus information online” (Laura Garcia, First Draft).

- “The truth about coronavirus is scary. The global war on truth is even scarier.” (Caroline Orr, Canada’s National Observer).

- “A Handy List of Reputable Coronavirus Information” (Melissa Ryan, Medium).

For further discusion

What responsibilities come with free speech? What kinds of speech shouldn’t be permitted in a free society? Should all social media platforms ban and remove medical misinformation? Why or why not? Should social media companies treat misinformation about climate change (an issue where there is scientific consensus) the same as they do misinformation about COVID-19? Why do you think crises and tragic events tend to spark conspiracy theories?

Additional resources

“Sifting Through the Coronavirus Pandemic,” an information literacy hub created by Mike Caulfield, a digital literacy expert at Washington State University. (Note: While we fully endorse Caulfield’s SIFT method, it is not affiliated with this newsletter.)

Also note: The News Literacy Project is working on a resource response for educators teaching news literacy during this outbreak. In the meantime, you can start by reinforcing these five tips with students:

- Recognize the effects of your information decisions.

Just as your decisions and actions can inadvertently spread the virus itself, your conduct online can influence others and have consequences in the real world. - Take 20 seconds to practice good information hygiene.

Like the time recommended for effective hand-washing, 20 seconds is all that is needed to eliminate a significant chunk of the misinformation we encounter: Scan comments for fact checks, do a quick search for the specific assertion, look for reliable sources and don’t spread any unsourced claims.

- Filter your information sources.

The World Health Organization cited the “over-abundance of information” (PDF) as a cause of the current “infodemic.” While a diverse and varied information diet is generally important, so is the ability to focus your attention on credible sources. - Learn to spot misinformation patterns.

Rumors about this virus often cite second- and thirdhand connections to anonymous people in positions of authority, such as health or government officials. Don’t be fooled by “copy-and-paste” hearsay. - Help sanitize social media feeds.

Flag misinformation when you see it on social media. Failing to do so leaves behind an infected post that will influence those who see it after you.

Adams discusses coronavirus misinformation on NPR

Peter Adams, NLP’s senior vice president of education, talked with NPR’s Michel Martin about misinformation surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic on the March 14 edition of All Things Considered.

He began by describing the types of misinformation being spread about SARS-CoV-2, the strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19. “This pandemic has brought out a really clear picture of the kinds of things that tend to circulate in the misinformation ecosystem,” Adams said, but “more intensified and, obviously, with higher stakes.”

As an example, he added, he has seen “everything from miracle cures and alternative medicine recommendations — some of which are dangerous, most of which are completely ineffective — to anti-vaccination activists using this to push their agenda and their falsehoods,” along with “conspiracy theorists jumping in, some disinformation agents and online trolls.”

“The equivalent of taking 20 seconds and washing your hands is very much the same in the information space … investigate the source, do a quick Google search, stay skeptical.”

It’s not just bad actors, though. As typically happens when health or safety is at stake, he said, misinformation is often spread inadvertently by well-intentioned people trying to make sense of a scary and rapidly unfolding situation and want to protect their friends and family.

Adams also offered easy-to-adopt steps to distinguish credible information from false or misleading content. “The equivalent of taking 20 seconds and washing your hands is very much the same in the information space,” he said. If everyone can “take 20 seconds, investigate the source, do a quick Google search, stay skeptical, we can eliminate a great deal of the confusion and misinformation out there.”

Listen to the interview — or read the transcript — to help you and your family and friends stay well —and well-informed — during this outbreak.

YouTube’s efforts to restrain conspiracy theories have mixed results

A new study (PDF) shows that YouTube’s efforts to limit the reach of harmful conspiracy theory videos via its algorithmic recommendations have produced positive, but inconsistent, results. From October 2018 to February 2020, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley recorded more than 8 million “Up next” video recommendations made by the YouTube algorithm in a set of more than a thousand “of the most popular news and informational channels in the U.S.”

The data showed a significant and steady decrease in recommendations of conspiracy videos from January 2019 — when YouTube announced that it was taking steps to reduce recommendations of “content that could misinform users in harmful ways” — to June 2019, when the platform touted a 50% reduction in such recommendations. After that, though, the rate of recommendations of conspiracy theory videos increased — possibly, the study noted, because YouTube may have relaxed its efforts or because content creators may have figured out how to avoid being flagged.

The study also found evidence that YouTube’s reduction efforts yielded significantly stronger results on specific subjects, suggesting that the platform can minimize the spread of specific kinds of harmful misinformation when it chooses to.

Note

Because researchers have been unable to track personalized recommendations at scale, this study and others like it have relied on analyses of algorithmic recommendations made to “logged-out” accounts, meaning that researchers could not access and analyze data from accounts whose individual “watch histories” factor into algorithmic recommendations. The study’s authors pointed out that users “with a history of watching conspiratorial content will see higher proportions of recommended conspiracies.” A YouTube spokesperson, Farshad Shadloo, told The New York Times that the study’s focus on nonpersonalized (“logged-out”) recommendations means that its results don’t represent actual users’ experience of the platform.

Discuss

Is YouTube the primary source of information for young people? Has YouTube replaced television for them? What are the advantages of watching videos on YouTube as opposed to programs on television? What are some of the disadvantages? Why don’t major television networks struggle with the proliferation of conspiracy theories on their channels? Does YouTube’s recommendation algorithm — which makes suggestions for the platform’s 2 billion monthly users — have too much power? Should YouTube be regulated by an outside agency, or not? Why?

Consider this idea

Have students select 10 popular YouTube channels that they consider to be credible sources of news and other information, then document the “Up next” algorithm’s recommendations on those channels’ videos for a period of time. Compile the data and share the findings, including with the study’s authors.

Classroom Connection: Bloomberg’s social media strategy tests the rules

The innovative and aggressive social media strategy of Michael Bloomberg’s presidential campaign is testing the limits of newly established political advertising policies at social media companies.

Earlier this month, the campaign paid people behind highly influential accounts on Instagram to post humorous memes supporting Bloomberg’s candidacy. In response, Facebook — which owns Instagram — said that it would allow such posts, but only if they adhered to its disclosure guidelines. This prompted the accounts involved in the Bloomberg meme promotion to do so retroactively. Facebook also said the resulting memes are not subject to approval like other political ads. The company did say that unlike posts by candidates and campaigns, they will be subject to Facebook’s third-party fact-checking program.

Paid organizers

More recently, the Bloomberg campaign hired hundreds of “deputy field organizers,” ordinary people who agree to promote Bloomberg as a candidate on their personal and online networks. The organizers are paid $2,500 a month and are sent pre-approved campaign messaging to use (or adapt) in text messages and social media posts. But the strategy resulted in dozens of identical posts that resembled automated messages posted by bots. After the Los Angeles Times asked Twitter about the posts, the platform last week announced that the practice violated its platform manipulation and spam policy. It also said it was suspending 70 pro-Bloomberg accounts.

Finally, the campaign on Thursday published a video composed of clips from last week’s Democratic debate that added a long, awkward pause, baffled looks from the other candidates and cricket sound effects after Bloomberg said, “I’m the only one here that, I think, that’s ever started a business, is that fair?” The post touched off an online debate about the line between manipulated and satirical content and how social media platforms should respond to the video. Twitter — which confirmed last week that it is working on a new policy to address misinformation after a demonstration of new features was leaked — said the video would likely violate its new policy against manipulated media. However it also said it wouldn’t retroactively apply a disclaimer. Facebook said the video would be protected under the platform’s existing exemption for parody or satire.

Please note

Russian disinformation agents also used some of Bloomberg’s social media strategy tactics in 2016.

For the classroom

Is the Bloomberg campaign’s social media strategy savvy and smart, or misleading and unethical? Do you agree with the ways Twitter and Facebook (including Instagram) have handled the issues that have arisen? Do the memes that the campaign paid influential Instagram users to make qualify as “sponsored content”? What about the posts and text messages from the campaign’s “deputy field organizers”?

Related reading

“Bloomberg News’s Dilemma: How to Cover a Boss Seeking the Presidency” (Michael M. Grynbaum, The New York Times).

Nominate a student for Gwen Ifill award

Gwen Ifill moderated a panel at NLP’s fall 2013 forum where journalists discussed “America’s Changing Role in the World and How the Press Covers It.” Photo by Rick Reinhard

Are you an educator who has used the Checkology® virtual classroom this school year and have an outstanding young woman of color in your class who has particularly benefited from the platform? If so, we hope you will nominate her to be considered for a special award from the News Literacy Project: the Gwen Ifill Student of the Year Award.

Gwen was an exemplary and groundbreaking journalist (and an NLP board member) whom we lost far too soon. After her death in 2016, we established an annual award to honor her memory and express our appreciation for her extraordinary service to NLP and her commitment to our mission.

Gwen Ifill award honors her legacy

This award is presented to female students of color who represent the values Gwen brought to journalism as the first woman and first African American to serve as moderator of PBS’ Washington Week and as a member (with Judy Woodruff) of the first female co-anchor team of a network news broadcast on PBS NewsHour. The winner is acknowledged at a special event and receives an engraved glass plaque with an etched photo of Gwen and a $250 gift card.

You can read about last year’s winner, Valeria Luquin, here and watch a short video about her.

Nominate students by March 1

The short nomination form is available here; you may nominate more than one student, but please use a separate form for each. The deadline is Sunday, March 1. A small group of candidates will be selected to advance to a final round for which they submit short essays about their experience with Checkology and the importance of news literacy.

We feel privileged to have the opportunity to honor Gwen’s memory and inspire the next generation of journalists in this way. Thank you for helping us do so.

How to know what to trust: Seven steps

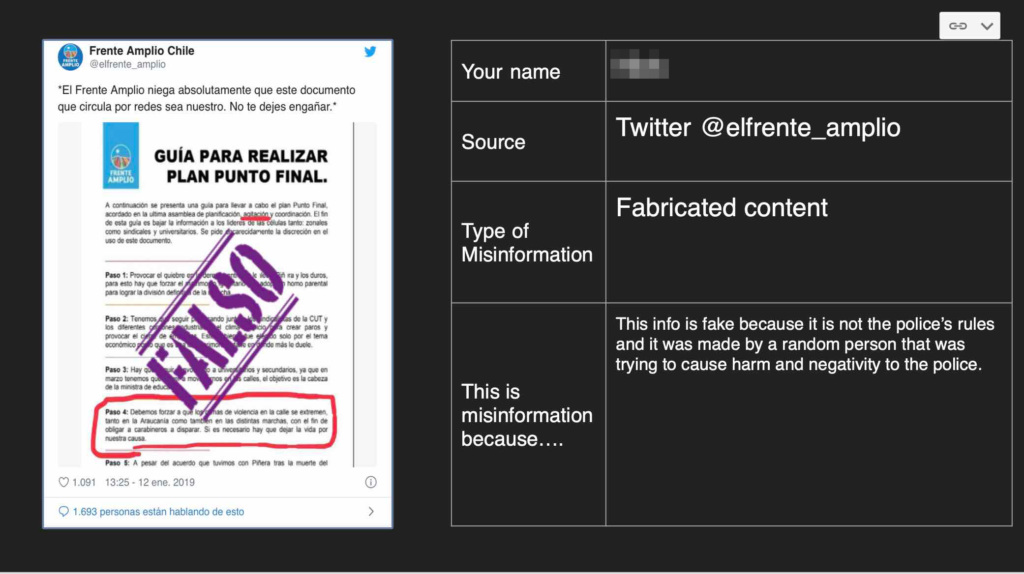

Misinformation comes at us every day, across a plethora of platforms and through myriad methods. It’s all part of an increasingly complex and fraught information landscape. But what exactly do we mean when we say misinformation?

Misinformation comes at us every day, across a plethora of platforms and through myriad methods. It’s all part of an increasingly complex and fraught information landscape. But what exactly do we mean when we say misinformation?

We define it as information that is misleading, erroneous or false. While misinformation is sometimes created and shared intentionally, it is often created unintentionally or as humor — satire, for example —that others later mistake as a serious claim.

Misinformation can include content that is wholly fabricated, taken out of context or manipulated in some way. Purveyors of misinformation often seek to exploit our beliefs and values, stoke our fears and generate anger and outrage. For example, during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, foreign governments, as well as organizations and individuals abroad and within the United States, flooded social media with disinformation. This nefarious form of misinformation — is designed to sow discord, often around political issues and campaigns.

Don’t throw up your hands

While we might feel overwhelmed by the volume, frequency and increasing sophistication of misinformation in all its forms — from deepfakes and doctored images to outright propaganda — we can push back and regain a sense of control. News literacy skills that are easy to adopt can help us become smart news consumers.

To begin, we have identified seven simple steps that help you know what to trust. These steps can apply to information you encounter in the moment and over time. As these behaviors become ingrained in your information consumption habits, you will deepen your expertise.

You will then become savvy enough to flag misinformation when you see it, warn others about misleading content and help protect them from being exploited. In this way, you become part of the solution to the misinformation problem.

So start right here, right now by exploring the seven simple steps to learn “how to know what to trust.”

Exploiting trust in local news: Bogus news outlets

A BuzzFeed News investigation last week exposed a large network of bogus local and financial news websites — replete with recycled press releases and plagiarized news stories — designed to make money in a number of ways. Matt McGorty*, who has experience in the financial information industry, established some of the sites as far back as 2015, BuzzFeed reported.

Many of the fraudulent sites, some of which are no longer live, had names such as the Livingston Ledger or the Denton Daily to give people the impression they were small but legitimate local outlets. McGorty* used plagiarized news stories to get the sites included in Google News results and to optimize rankings in general search results, and made money through ad revenue, commissions for financial email sign-ups and referral fees for questionable investment opportunities.

Exploiting trust

The network is the latest example of an attempt to capitalize on two aspects of the current information environment: the public’s trust in local news organizations and the likelihood that people will not recognize bogus but legitimate-sounding sources of local news. During the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, Russian disinformation operatives created Twitter accounts such as @ElPasoTopNews and @MilwaukeeVoice to amplify divisive — but real — local news stories from legitimate outlets. More recently, homegrown political operatives — including campaigns, political action committees and partisan activists on both the left and right — have used the same tactic to advance their agendas.

Late last year, The Lansing State Journal and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University uncovered a network of 450 bogus news websites. At least 189 of the sites posed as local news outlets and used algorithms to convert press releases into “pink slime” local news stories that supported conservative talking points.

* UPDATE (April 21, 2020): This item initially said that Matt McGorty and his brother established the network of phony news sites. BuzzFeed News updated its report on April 2 after being told by Matt McGorty that his brother “had nothing to do with any of this.”

Learn more

- “A website wanted to restore trust in the media. It’s actually a political operation.” (Gabby Deutch, The Washington Post).

- “The Billion-Dollar Disinformation Campaign to Reelect the President” (McKay Coppins, The Atlantic).

Test yourself

NLP’s “Which Is Legit?” quiz.

For teachers

Why do you think so many different kinds of people and organizations (foreign disinformation agents, con artists, clickbait farmers, political activists, etc.) are using bogus local news outlets as vehicles for their content?

Idea: As a class, create a list of all the legitimate (standards-based) local news outlets in your community, then create Wikipedia pages for any that do not currently have one. (Big thanks to Mike Caulfield, director of blended and networked learning at Washington State University Vancouver, for this idea.)

Another idea: Have students brainstorm ideas for protecting people in their communities from being taken in by impostor local news sources, then vote for the best one. Make that idea a class assignment, or let students choose one of several ideas to work on in teams.

To get stories like this delivered to your inbox every week, subscribe to our newsletter, The Sift®.

Classroom Connection: Coronavirus misinformation already pandemic

As rapidly as the coronavirus has spread in recent weeks, viral misinformation about the disease has far outpaced it, reaching millions of people on every continent in far less time. Dozens of photos and videos — of masked medical personnel; of people collapsing, being loaded into ambulances, lying in the street, and waiting in quarantine — have rocketed across social media along with dangerous “cures,” conspiracy theories, more conspiracy theories, school hoaxes, false figures for cases and deaths, faked video of “infected” blood, and disinformation from Chinese government sources.

In short, while the outbreak has yet (as of Feb. 2) to be classified as a pandemic, the misinformation about the new strain of coronavirus has achieved that status many times over.

Coronavirus misinformation as case study

As worrisome as this is, coronavirus misinformation patterns can also be used as a case study with students. Just as epidemiologists can glean valuable insights from outbreaks of disease, students can analyze the plethora of coronavirus rumors to refine their understanding of why and how falsehoods spread.

The two phenomena share some factors. As New York University journalism professor Charles Seife points out in the opening chapter of his 2014 book Virtual Unreality, the three epidemiological factors that determine how a disease spreads — transmissibility, persistence and interconnectedness — can also be used to explain the ways misinformation spreads online. Digital information is highly transmissible (easy to replicate) and highly persistent (easy to store and search) — and circulates in the most interconnected information environment the world has ever known.

But coronavirus rumors and other types of alarming medical misinformation have a specific potential for virality because they tap into extremely strong emotions. Rumors about infectious diseases incite fear, causing people to react emotionally and share those rumors with loved ones out of a strong desire to protect them. Medical information is also highly specialized, which increases the likelihood that people — perhaps especially conspiracy theorists — will misunderstand information they’ve dug up themselves (such as the results of a mock pandemic exercise, or old patents for a different strain of the coronavirus).

Finally, while photos and video related to many topics are easy to persuasively present in false contexts, images and footage of people suffering from medical conditions are among the easiest to shift to new (and false) contexts.

Please note

Two other recent events generated a surge of out-of-context photos and video for the same reason: the killing of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani sparked a wave of false military strike visuals, and the recent wildfires in Australia prompted years-old photos of other wildfires to circulate.

For the classroom

What does it mean for a rumor to “go viral”? How is the outbreak of a disease similar to the spread of viral misinformation? What can the steps taken by medical professionals to control the spread of disease teach us about controlling the spread of misinformation?

Related reading

- “Panic and fear might be limiting human reasoning and fueling hoaxes about coronavirus” (Cristina Tardáguila, Poynter).

- “A Site Tied To Steve Bannon Is Writing Fake News About The Coronavirus” (Jane Lytvynenko, BuzzFeed News).

- “How tech companies are scrambling to deal with coronavirus hoaxes” (Shirin Ghaffary and Rebecca Heilweil, Vox).

A great week, thanks to you!

With our partner, The E.W. Scripps Company, we at the News Literacy Project are grateful to all of the educators, students, journalists and members of the public who joined us for National News Literacy Week.

We had terrific participation on social media and through Scripps’ local TV stations across the country, and high visibility thanks to donated ad space from news organizations across the country (from a small-town weekly in Rhode Island, The Valley Breeze, to the Los Angeles Times, along with The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Associated Press, NPR and many more). National News Literacy Week was even featured on Nasdaq’s billboards in Times Square!

National News Literacy Week, promoted on Nasdaq’s billboards. Darragh Worland / The News Literacy Project

The Philadelphia Inquirer published an op-ed by our founder and CEO, Alan Miller, that explained the critical need for news literacy. The Houston Chronicle published an op-ed by Miller and Adam Symson, Scripps’ president and CEO, about the importance of sticking to facts. The Roanoke (Virginia) Times shared Miller’s thoughts on why news literacy is vital to democracy. Editors at other news organizations joined in, writing their own editorials and publishing opinion columns in support of news literacy education. They included the San Francisco Chronicle, the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, the Post Bulletin (Rochester, Minnesota), The Patriot-News (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) and The Advocate-Messenger (Danville, Kentucky).

Student reports

On the broadcast and interactive side, National News Literacy Week was featured in promotions on Scripps’ national media brands, including its podcast company, Stitcher, and its multiplatform news network, Newsy. Particularly impressive were the reports that aired on Scripps’ TV stations around the country, co-produced by each station’s journalists and local students.

The students came up with issues that were of concern to them, then worked with the Scripps journalists to put together reports on such teen-focused topics as career training programs, disparities between boys’ and girls’ sports at high schools, and young people’s use of social media, along with broader concerns, such as mental health, climate change in the 2020 election and local cases of missing or murdered indigenous women.

In addition, we featured resources, tips and tools relating to each day’s National News Literacy Week theme (you’ll need to register for our Checkology® virtual classroom as a Basic user to see the lessons):

- Navigating the information landscape (“InfoZones”).

- Identifying standards-based journalism (“Practicing Quality Journalism”).

- Understanding bias — your own and others’ (“Understanding Bias”).

- Celebrating the role of a free press (“Democracy’s Watchdog”).

- Recognizing misinformation (“Misinformation”).

Maintaining news literacy skills

And while National News Literacy Week may be over, news literacy remains an urgent and persistent need. We encourage you to keep your skills sharp by using some of the tips we shared (click the links to learn more):

- Determine if it’s actually news (or if it’s something else). First, consider its primary purpose: Is it informing you, or was it designed to persuade, entertain, or sell?

- Slow down for breaking news. Producing a credible report as events unfold takes time. Especially in early stories, pay attention to whether what’s being claimed has been verified.

- Practice lateral reading. If you have any questions about what you’re seeing or hearing, use other sources to confirm it as you continue to read, watch or listen.

- Take notes, photos or videos. “Citizen watchdogs” can work with journalists to bring attention to matters of importance.

- Know how to spot a conspiracy theory. Just because something can’t be disproved doesn’t mean that it’s true.

And find out just how much you learned during National News Literacy Week by taking this quiz: “How news-literate are you?”

Remember, when you put your news literacy skills to work, you’re no longer part of the misinformation problem. You’re part of the solution.

This item was updated on Feb. 4 with a photo, with links to editorials and columns published in support of National News Literacy Week, and with links to the daily themes.

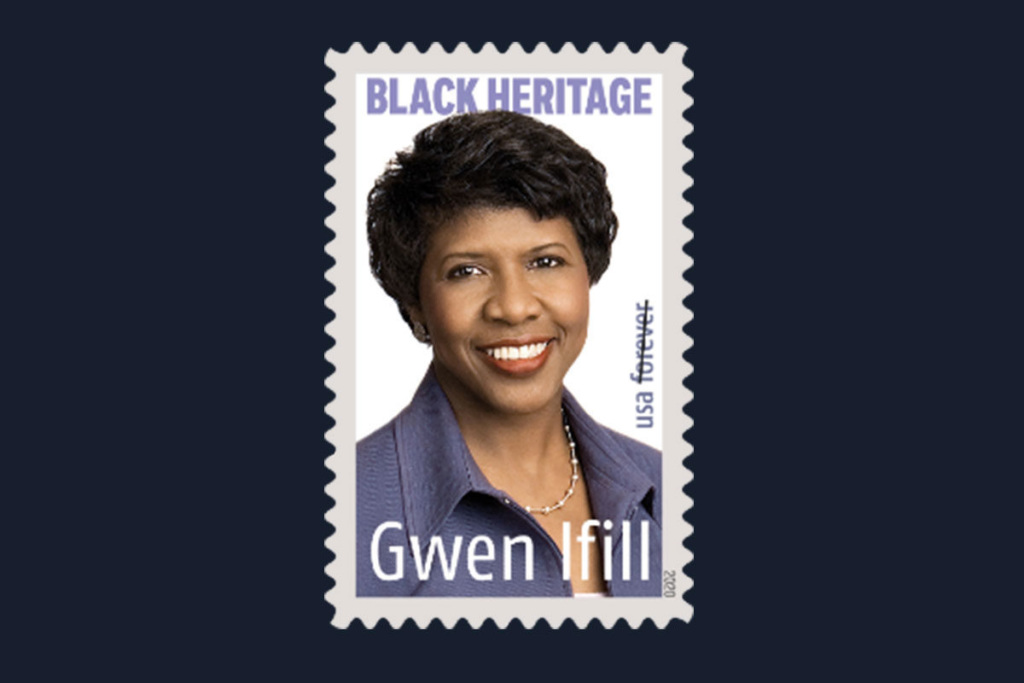

Gwen Ifill honored with Forever stamp

Gwen Ifill, who was one of most respected journalists of her generation and a longtime friend and supporter of the News Literacy Project, is being honored today by the U.S. Postal Service with a Forever stamp.

“Gwen Ifill was an extraordinary journalist and colleague, a relentless champion of news literacy and a treasured friend,” said Alan Miller, NLP’s founder and CEO, who worked closely with Ifill during her tenure on NLP’s Board of Directors. “She remains an inspiration to us to this day.”

Ifill, who died in 2016, had a distinguished journalism career at the Boston Herald American, The Evening Sun in Baltimore, The Washington Post, The New York Times and NBC before joining PBS in 1999. She was the first woman and first African American to serve as moderator of Washington Week and was a member (with Judy Woodruff) of the first female co-anchor team of a network news broadcast on PBS NewsHour.

NLP involvement

She was involved with NLP from the beginning, taking an active role in five high-profile events, attending many more, and talking up NLP at every opportunity. She joined the board in 2011 and remained a member until her death. As a member of its governance committee, she pushed to seek members who would bring expertise, experience, diversity and a strong commitment to NLP’s mission.

Since 2017, NLP has recognized her significant accomplishments in journalism and her commitment to news literacy with the Gwen Ifill Student of the Year Award, presented annually to a female student of color who represents the values Ifill brought to journalism. A committee of NLP staff and board members selects the honoree.

The dedication of the 43rd stamp in the postal service’s Black Heritage series is being held at Washington’s Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church, which Ifill attended for years. The stamp, available in panes of 20, features a photo of Ifill taken by Robert Severi in 2008.

News of the dedication will be available on social media with the hashtags #GwenIfillForever and #BlackHeritageStamps.

Take part in National News Literacy Week

The News Literacy Project (NLP) and The E.W. Scripps Company are joining forces for National News Literacy Week (Jan. 27-31) — an initiative that will raise awareness of news literacy as a fundamental life skill and highlight the vital role of a free press in a healthy democracy.

This campaign will provide educators, students and the public with easy-to-adopt tools and tips for becoming news-literate. Each day’s theme aligns with a lesson in our Checkology® virtual classroom that will be available (for that day only) at NewsLiteracyWeek.org. Our resources will also be shared on Scripps’ and NLP’s social media channels throughout the week.

The themes are:

- Monday, Jan. 27 — Navigating the information landscape.

- Tuesday, Jan. 28 — Identifying standards-based journalism.

- Wednesday, Jan. 29 — Understanding bias — your own and others’.

- Thursday, Jan. 30 — Celebrating the role of a free press.

- Friday, Jan. 31 — Recognizing misinformation.

You can also test your news literacy skills with Informable, NLP’s free mobile app, which uses a gamelike format to assess and improve users’ ability to distinguish between news and other types of information.

Throughout National News Literacy Week, Scripps’ local television stations and Newsy, its multiplatform news brand, will air reports related to news literacy. Scripps’ local and national media brands are featuring “The Easiest Quiz of All Time” — a multiplatform news literacy campaign that emphasizes the importance of double-checking facts. Scripps journalists are working with high schools in their communities to produce original pieces of student journalism that will premiere throughout the week on-air and online across Scripps’ stations; a selection will be available at NewsLiteracyWeek.org.

Please join us by using these resources to improve your own news literacy skills, sharing them with your friends and family, and engaging with us on social media (#NewsLiteracyWeek).

Classroom Connection: Teen Vogue’s Facebook piece deemed a ‘misunderstanding’

A flattering piece about Facebook posted by Teen Vogue was the source of much confusion last week. “How Facebook Is Helping Ensure the Integrity of the 2020 Election” appeared on Jan. 8 without any indication that it was a piece of sponsored content, paid for by the world’s largest social media company.

Soon after it was posted, an editor’s note — “This is sponsored editorial content” — was added at the top. Later, that note was removed. Finally, the entire piece disappeared. Lauren Rearick, a contributor to Teen Vogue, was at one point listed as the author, but she told Mashable that she didn’t write it. Asked on Twitter what the piece was, Teen Vogue replied: “literally idk.”

In a post that was later deleted, Facebook’s chief operating officer, Sheryl Sandberg, called it a “great Teen Vogue piece about five incredible women protecting elections on Facebook.” A company spokeswoman initially said that the piece was “purely editorial”; later, Facebook said that “there was a misunderstanding” and that it indeed “had a paid partnership with Teen Vogue related to their women’s summit, which included sponsored content.”

In its statement, Teen Vogue said: “We made a series of errors labeling this piece, and we apologize for any confusion this may have caused. We don’t take our audience’s trust for granted, and ultimately decided that the piece should be taken down entirely to avoid further confusion.”

Ideas for discussion

What is the difference between a piece of sponsored content (also known as “branded content” or “native advertising”) and a piece of journalism? Is it important for news outlets to clearly label such content? Why? If you were in charge of Teen Vogue, how would you have handled the piece about Facebook? Was Teen Vogue right to delete it? Did it sufficiently explain how the mistakes in handling the piece were made? Does this change the level of trust you have in Teen Vogue? Why or why not?

Related activities

Have students find examples of sponsored content published by up to five different standards-based news organizations. Ask students to note the differences between the sponsored content and the straight news coverage from the same outlet. In what ways are they similar? In what ways are they different? Do they look the same, or are they labeled differently?

Learn more

“Branded Content,” a lesson in the Checkology® virtual classroom (Premium account required).

‘Black PR’: An industry built around sowing disinformation

Coordinated efforts to disseminate propaganda online are supported by “a worldwide industry of PR and marketing firms ready to deploy fake accounts, false narratives, and pseudo news websites for the right price,” according to a Jan. 6 report by BuzzFeed News and The Reporter, an investigative news outlet in Taiwan.

Such businesses — which in the public relations industry are described as practicing “black PR” — operate all over the world. They use a variety of increasingly sophisticated tactics to try to “change reality” in ways that benefit their clients, which include corporations, governments, politicians and political parties.

These tactics include publishing “fake news” stories, then using legions of fake social media accounts to amplify those and other messages. This practice boosts their ranking in search results and helps spread them across social media platforms and in groups on private messaging apps. The fake accounts are also used to make comments designed to give false weight to specific sentiments, both positive and negative, in line with their clients’ interests. (This form of artificial grassroots expression is also known as “astroturfing.”)

Some of these companies are developing advanced disinformation strategies and using emerging technologies, the BuzzFeed report found. The Archimedes Group, an Israeli “black PR” firm, created fake fact-checking groups to promote its clients’ interests. It also managed social media pages both against and for a Nigerian politician, Atiku Abubakar — ostensibly to damage him as well as to identify his supporters “in order to target them with anti-Abubakar content later.”

A “black PR” practitioner in Taiwan — Peng Kuan Chin, who is featured in the BuzzFeed article — has built an “end-to-end online manipulation system” that uses artificial intelligence to scrape organic articles and social media posts for key phrases. It then reassembles them into algorithmically generated pieces, publishes these articles to a group of websites Peng operates, and pushes the links out through thousands of automated social media accounts he controls.

Note

Social media platforms’ actions against “black PR” tactics include removing accounts, pages and groups that engage in such activity, yet the practice continues to grow.

Learn more

Demand for Deceit: How the Way We Think Drives Disinformation (Samuel Woolley and Katie Joseff, National Endowment for Democracy).

For teachers

Can ordinary people avoid being influenced by professional disinformation efforts online? What steps are social media platforms taking to counteract these practices? What steps aren’t they taking that they should? What steps can you take to ensure the information you use as the basis for your decisions is credible? What kind of information environment might these kinds of practices — especially those that are automated at a large scale — produce if they are left unchecked? How might these kinds of practices affect elections in the coming years?

Miller looks at news literacy’s impact on local news

As part of its local news initiative, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation asked NLP’s founder and CEO, Alan C. Miller, to consider how news literacy correlates with improved trust and understanding between the public and local news outlets. He immediately saw the connection and shared his thoughts, which were posted Jan. 9 on the foundation’s website. (Disclosure: Knight Foundation is NLP’s largest funder.)

“Supporting news literacy education at the local level will lead to deeper interest in the work of local news outlets — the ones that hold local businesses and local elected officials accountable,” Miller wrote. “When news consumers learn how to verify the credibility of information, they become empowered. Our students tell us that as a result of lessons in our Checkology® virtual classroom, they plan to become more engaged in civic issues and more active in their communities.”

Please read Miller’s essay — and after you do, contact your local school to support the inclusion of news literacy in its students’ education experience.

Classroom Connection: New York Times op-ed backlash

A Dec. 27 opinion column by Bret Stephens in The New York Times headlined “The Secrets of Jewish Genius” drew a wave of criticism last week.

In his original column, Stephens lauded the intelligence of Ashkenazi Jews, citing a 2005 paper that was published in the Journal of Biosocial Science, which until 1969 was named The Eugenics Review. The article was co-authored by Henry Harpending, whom the Southern Poverty Law Center labeled an “extremist” with a “white nationalist” ideology.

On Dec. 29, the Times’ opinion section said on Twitter that the column had “been edited to remove a reference to a paper widely disputed as advancing a racist hypothesis,” and an editors’ note had been added.

“After publication Mr. Stephens and his editors learned that one of the paper’s authors, who died in 2016, promoted racist views. Mr. Stephens was not endorsing the study or its authors’ views, but it was a mistake to cite it uncritically. The effect was to leave an impression with many readers that Mr. Stephens was arguing that Jews are genetically superior. That was not his intent,” the editors’ note said, adding that the reference to the study was removed from the column.

However, Jack Shafer of Politico argued that Jewish genetic superiority was exactly what Stephens was claiming, based on the sections removed from the original column. “If you’re going to edit a piece, the smart move is to edit before it publishes,” Shafer wrote.

James Bennet, the Times’ editorial page editor, said Stephens’ column was edited and fact-checked before it was published, according to a report by Michael Calderone, also of Politico. Bennet did not address how references to the research paper made it through the editing process. The editors’ note also did not explain why all mentions of “Ashkenazi” Jews were removed from the revised piece, Calderone noted. Stephens has not commented.

This is not the first time the winner of the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for commentary while at The Wall Street Journal has sparked controversy since joining the Times in 2017. In August, he took issue with a critical tweet by a George Washington University associate professor — which jokingly referred to Stephens as a bedbug — and responded by email to the professor and copied his provost. In addition, his first column in April 2017 raised questions about scientific evidence to support climate change that prompted Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr., chairman of the board of The New York Times Company and publisher of the Times in 2017, to send an email appealing to readers who indicated that the hiring of Stephens led them to cancel their subscriptions.

Related

- “The dilemma that is Times columnist Bret Stephens” (Mathew Ingram, Columbia Journalism Review).

- “A New York Times columnist set out to praise ‘Jewish brilliance.’ The result was another explosive controversy.” (Paul Farhi, The Washington Post).

- “The New York Times ran a disturbing op-ed. But the backlash misses the mark” (Siva Vaidhyanathan, The Guardian).

For Teachers

Discuss: Did the Times handle the controversy over Stephens’ column properly? Was the editors’ note enough? If not, what was missing, and what else should it have included? What should Stephens and/or editors have done differently before the column was published, if anything? Do you think it is part of opinion writers’ jobs to provoke controversy? Do you think it’s important for news outlets’ opinion editors to present a range of political viewpoints? How should opinion editors decide when a viewpoint falls outside the bounds of acceptable discourse?

News literacy resolutions for a new year

Making New Year’s resolutions is easy; keeping them is not.

This year, you can adopt a meaningful resolution that is easy to keep long after we ring in another new year.

So join NLP in resolving to become more news-literate in 2020. Here’s how, in three simple steps.

Classroom Connection: Artistic license or smear?

Clint Eastwood’s new movie, Richard Jewell, has come under fire for its portrayal of Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Kathy Scruggs, igniting a debate about Hollywood’s depictions of female journalists.

The film, which opened nationwide on Dec. 13, tells the story of Jewell, the security guard hero-turned-suspect in the July 27, 1996, bombing at Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park that resulted in two deaths and injuries to more than 100 people.

In one scene, Scruggs (Olivia Wilde) flirts with an FBI agent (Jon Hamm) who was one of her sources; the film insinuates that she traded sex with him for the information that Jewell was being investigated as a suspect. (The Journal-Constitution was the first to report that Jewell — who discovered a backpack containing a pipe bomb, alerted law enforcement and helped to evacuate the area — was the focus of the federal investigation.)

Lawyers’ demands

In a letter sent Dec. 9 to Eastwood, screenwriter Billy Ray, Warner Bros. and others, lawyers for the Journal-Constitution and its parent company, Cox Enterprises, described the movie’s treatment of Scruggs, who died in 2001, as “false and malicious” and “extremely defamatory and damaging.” They demanded that the studio and the filmmakers issue a statement “publicly acknowledging that some events were imagined for dramatic purposes and [that] artistic license and dramatization were used in the film’s portrayal of events and characters” and that “a prominent disclaimer” to that effect be added to the film.

Warner Bros. called the Journal-Constitution’s claims “baseless” and defended the movie, stating: “The film is based on a wide range of highly credible source material. … It is unfortunate and the ultimate irony that the Atlanta Journal Constitution, having been a part of the rush to judgment of Richard Jewell, is now trying to malign our filmmakers and cast.”

Dozens of journalists have criticized the film’s depiction of Scruggs, calling the intimation that she traded sex for information an offensive, sexist trope and noting that in reality, female journalists are often “propositioned, pawed and threatened” by sources. Scruggs’ brother, her former colleagues and her friends have also come to her defense.

Libel suit

Jewell, who was officially cleared as a suspect three months after the bombing, sued the Journal-Constitution for libel in 1997, contending that its reporting had damaged his reputation. Two years later, a trial court judge ruled that because Jewell had made himself available for a number of interviews following the bombing, he was to be considered a “limited purpose public figure” for the purposes of the suit — meaning that to win his case, he would have to prove that the paper knowingly published false information about him.

In 2011, the Georgia Court of Appeals found that the Journal-Constitution’s articles about Jewell “were substantially true at the time they were published” and upheld the trial court’s dismissal of the case. The following year, the state Supreme Court declined to review the appeals court’s decision, ending a 15-year legal fight. The media’s coverage of Jewell, who died in 2007 (the lawsuit was continued by the executors of his estate), even became a case study in university journalism programs.

Related

- “Fox News Host Jesse Watters Called Out by Women’s Groups Over ‘Richard Jewell’ Remarks” (Jeremy Barr, The Hollywood Reporter).

- “Opinion: Film tries to fix one reputation, attacks another” (Kevin Riley, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution).

- “Man Accused of Smacking Reporter’s Rear on Live TV Is Charged” (Johnny Diaz, The New York Times).

For teachers

Discuss: In your experience, how are journalists portrayed in movies and television programs? Are the depictions fair? Are they accurate? Do you think the depictions of female and male journalists differ in any way? Do you think that Richard Jewell should include a disclaimer, as the Journal-Constitution has demanded?

Idea: Have students research Scruggs and the Journal-Constitution’s coverage of Jewell. Based on students’ research, what did the movie get right about Scruggs, and what did it get wrong?

Another idea: Divide students into small groups to discuss how journalists are depicted in films and television programs. Have each group compile a list of five movies and/or shows in which journalists play a significant role and analyze how journalists were portrayed in them.

School librarian calls Checkology ‘priceless’ for teaching research skills

You might be surprised to learn what has students buzzing in the hallways of The Bolles School, a private school in Jacksonville, Florida.

It’s Jaime Sanborn’s Information Literacy course. Here’s what she has overheard them saying:

“What is Ms. Sanborn teaching?”

“She’s teaching us how to research. She’s teaching us how to think for ourselves.”

Sanborn, the middle school librarian at Bolles, is using NLP’s Checkology® virtual classroom in the semester-long research-driven elective that she is piloting this semester with seventh- and eighth-graders. She said that when she learned about the platform from other school librarians last year, she thought: “This is exactly what I want to teach them.”

Speaking her language

And Checkology speaks the language of librarians. “‘InfoZones’” — one of the platform’s foundational lessons — “is priceless. It is very similar to how librarians would teach source evaluation,” said Sanborn, who introduced a few Checkology lessons to sixth-graders in the 2018-19 school year.

“Every child is being influenced by social media as a source of information, not just entertainment, so I have to teach them how to navigate that. They believe everything they see,” she said.

So Sanborn might ask them: “You read this on Twitter. What makes this true? How can you verify it?” Reinforcing Checkology lessons with quizzes and related material, she reminds them to look for nuance, check sources and be mindful of language signaling that what they are reading, watching or hearing has a particular slant or is propaganda. She rounds out the Checkology component of her course with the “Misinformation,” “Introduction to Algorithms,” “Arguments & Evidence,” “The First Amendment,” “Branded Content” and “Understanding Bias” lessons.

Evaluating credibility

Sanborn wants students to understand that the internet is manipulating them through branded content (advertising designed to resemble news), algorithms that filter and narrow what they see, and viral memes rife with false, and often provocative, information. She stresses to her students that they must learn to find and evaluate the credibility of sources and content: “You are responsible for determining what is valuable and what is truth,” she tells them.

For students who aren’t yet using social media, the course is an eye-opener. “They can’t believe it when they see what is out there,” Sanborn said. “When they do get on social media, they will know what to expect and how to navigate it.”

Research skills for the real world

The internet, she reminds them, is a microcosm of society: “Think about the good and bad you see in the real world. All of what you see online is represented in the real world. You have to use the same life skills online and off.”

And her students are using what they are learning from Checkology every day. “They tell me that they have begun applying these skills when they are consuming news outside of the classroom,” Sanborn said.

It’s important to teach news literacy skills early, she said, noting how susceptible we all can be to confirmation bias — seeking information that simply reaffirms what we already believe.

“People don’t want to be uncomfortable,” she said of our disinclination to consider information that counters our beliefs. “Teaching kids at a young age is essential for them as researchers and participants in democracy.”

Informable app helps you build news literacy skills

If you are looking for an app that functions like a game and teaches you to be more news-literate, NLP has just the thing: Informable, our new mobile app.

It is designed to improve users’ ability to distinguish between several types of news and other information. Developed for both adults and students, Informable helps users practice four distinct news literacy skills using real-world examples in a game-like format. It is available now for download, at no charge, from the App Store (iOS) and Google Play (Android).

Accuracy, speed count

Informable (PDF) is intuitive and easy to navigate. It has four “brain training”-style modes, each with three levels:

- Checkable or Not? (Is each item fact-based or opinion-based?)

- Evidence or Not? (Does each item provide strong evidence for the claim it makes?)

- Ad or Not? (Is each item advertising or something else — news, opinion, personal endorsement on social media, etc.)?

- News or Opinion? (Is each item news or opinion?)

To advance, players must correctly identify at least seven of the 10 examples presented in each level. Points are awarded for accuracy and speed. Users can review their answers to learn more about each item and see why they were right or wrong.

Once users complete all three levels in all four modes, they encounter Mix-Up Mode, presenting random examples from all modes to simulate the information flow they might experience in real life. NLP will add new Mix-Up Mode levels several times a year.

Informable goes beyond the classroom

“Informable is the perfect complement to our Checkology® virtual classroom,” said Alan C. Miller, NLP founder and CEO. “We wanted to find a fun way to give our students’ parents — and the rest of the public — an opportunity to develop new habits of mind that will improve their ability to separate fact from fiction. Studies have shown that as we get older, we may be more likely to share misinformation. This app can help all of us become more discerning about the information we encounter.”

For more than a decade, the News Literacy Project has provided middle school and high school educators with tools and materials to teach their students how to navigate the challenging and complex information landscape and recognize credible information on their own. And with Informable, NLP is expanding beyond the classroom to offer educational resources to the general public.

Get it now:

Classroom connection: What ‘professional trolls’ want

While most people tend to think of internet trolls as obnoxious personas who provoke others into infuriating exchanges online, two disinformation experts at Clemson University argue that that “professional trolls” are far more likely to use positive ideological messages that affirm people’s existing beliefs to accomplish their goals of sowing division and distrust.

“Effective disinformation is embedded in an account you agree with,” Darren Linvill and Patrick Warren write in an article posted Nov. 25 on Rolling Stone’s website. “The professionals don’t push you away, they pull you toward them.”

Manipulating emotions

Professional disinformation practitioners also use accurate stories about valid issues — but selectively. For example, they might home in on stories that undermine trust in American institutions, or subtly manipulate our emotions by focusing on “cultural stress points,” such as religion or homophobia, that are known to provoke feelings of disgust toward people with different beliefs or ideologies. They also attack moderates, and share links and comments that support candidates and activists further away from the political center. And because so many of our social media profiles work the same way — selectively sharing information that affirms our viewpoints and existing beliefs, often by demonizing or belittling “the other side” — it’s challenging for social media companies and others to catch those doing so with a deceitful motive

Minimizing vulnerability

But Linvill and Warren, both associate professors at Clemson, also offer some advice to help minimize our vulnerability to these campaigns. These include the need to question our own biases, to stop believing and re-sharing posts from anonymous users online (for example, accounts using a hashtag we’re sympathetic with) and to engage in “digital civility” with those we disagree with. That is, seek common ground and resist the urge to dismiss or demean.

Russia’s goals, the authors warn, were “never just about elections”; they also were (and are) to encourage us “to vilify our neighbor and amplify our differences because, if we grow incapable of compromising, there can be no meaningful democracy.”

More on trolls and bots

“Why the fight against disinformation, sham accounts and trolls won’t be any easier in 2020” (Alexandra S. Levine, Nancy Scola, Steven Overly and Cristiano Lima, Politico).

“The not-so-simple science of social media ‘bots’” (Rory Smith and Carlotta Dotto, First Draft).

For Educators: ‘Digital civility’ exercise

As a project, have groups of students create concise, easy-to-remember “digital civility” guidelines for their friends and family members.

Checkology® receives Hundred’s Spotlight on Digital Wellbeing award

The News Literacy Project’s Checkology virtual classroom has received a 2019 Spotlight on Digital Wellbeing award from HundrED, an international nonprofit that promotes inspiring innovations in K-12 education.

The award recognizes our e-learning platform as one of 100 global innovations in 2019. The honorees are featured on HundrED’s website, each with a page that includes an overview, key data and videos. NLP’s NewsLitCamp® professional development program is also featured on the HundrED website.

“We are gratified that HundrED has recognized Checkology as a meaningful innovation in news literacy education,” said Alan C. Miller, NLP’s founder and CEO. “This recognition not only validates our work in the field but helps demonstrate the importance of bringing news literacy education to classrooms around the world.”

HundrED describes the importance of “digital wellbeing” to education in the context of the outsize role of the internet and electronic devices in the lives of young people: “This technological impact has many positive effects; for example, an increased scope in learning new knowledge and connecting with others from all over the world. However, it is becoming increasingly necessary for young people to adopt healthy habits when using digital devices so that they fully develop their mental, physical and social wellbeing.”

Award criteria

Programs and products submitted for Spotlight award consideration are judged on the following criteria:

- Innovativeness: Does the submission bring something new within the context?

- Impact: Does it show demonstrable evidence of impact, and has it been running for at least one year?

- Scalability: Can it be used, or is it already being used, in other areas or countries around the world?

Winners are selected by HundrED’s research team and 30 members of the HundrED Academy — stakeholders in the field of education who have expertise in the development of positive and healthy interactions with technology.

HundrED, which is based in Helsinki, Finland, announced its first collection of 100 inspiring global education innovations in October 2017.

Study: Students show ‘troubling’ lack of news literacy skills

A new report from the Stanford History Education Group has found little change in high school students’ ability to evaluate information online since 2016, when SHEG researchers released the results of a similar study.

This skill set — dubbed “civic online reasoning” by Stanford researchers — consists of the ability to recognize advertising, including branded content; to evaluate claims and evidence presented online; and to correctly distinguish between reliable and untrustworthy websites and other sources of information. (The executive summary of the 2016 study summed up “young people’s ability to reason about the information on the Internet” in one word: “bleak” — and the executive summary of the latest report acknowledged that “the results — if they can be summarized in a word — are troubling.”)

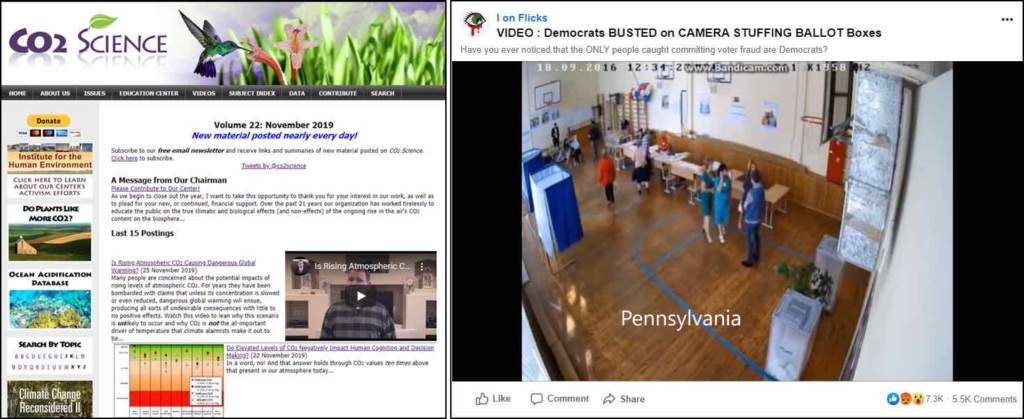

Two examples from the latest SHEG study: a website sponsored by the fossil fuel industry (left) and a video of Russian voter fraud presented out of context as Democratic voter fraud in the United States. Click the image to view a larger version.

For the latest findings, SHEG partnered with Gibson Consulting, an education research group, to assess 3,446 high school students from 16 school districts in 14 states. The students in the sample matched the demographic profile of high school students in the United States.

The researchers asked the students to complete six assessments with five distinct tasks, then assigned each response one of three ratings: Beginning (incorrect or showing use of “irrelevant strategies for evaluating online information”), Emerging (partially incorrect, or not fully showing sound reasoning) and Mastery (effective evaluation, reasoning and explanation).

A task asking students to evaluate the reliability of co2science.org, a website about climate change run by a group funded by fossil fuel companies, had the lowest scores. Fewer than 2% of student responses were given a Mastery rating; more than 96% were rated Beginning. In another task, students were presented with a Facebook post from a user named “I on Flicks” containing a video compilation that purported to show Democrats committing voter fraud during the 2016 Democratic primaries but was actually a collection of videos showing ballot-box stuffing in Russia. When asked if the video presented strong evidence of voter fraud in the United States, more than half (52%) said that it did. Only three respondents — 0.08% of the students surveyed — were able to find the source video.